Following the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Massachusetts Grand Army surrounded Boston and began to lay siege to it. The Massachusetts Committee of Safety quickly recognized that in order to drive the British army from the town, it had to starve them out.[1]

The British military had a longstanding practice of acquiring fresh provisions from local farmers. At first, Gen. Thomas Gage contemplated purchasing supplies from American farmers who lived on the islands in Boston Harbor. Unfortunately, many yeomen were reluctant to cooperate.[2] As a result, the general decided he would initiate military operations to forcefully seize necessary resources. Of course, the harbor islands only provided a limited amount of supplies. As a result, Gage was forced to rely heavily upon the long and tenuous communication lines to British possessions in Nova Scotia and the West Indies, and ultimately, back to England.

The Massachusetts Committee of Safety saw this logistical nightmare as an opportunity to loosen Gage’s hold on Boston. Massachusetts had a long history of privateering during the previous French wars and almost immediately turned to the practice as a method to drive His Majesty’s troops out of the town. Privateering, or “lawful piracy,” was the act of seizing enemy supply or military vessels by civilian-owned warships. Privateers operated under the authority of “Letters of Marque” issued from governmental authorities and were often, if not solely, motivated by the opportunity for profit.[3] Massachusetts authorities actively encouraged just about any person with a seaworthy vessel to partake in privateer operations and placed no limits on the number of ships receiving Letters of Marque.[4]

Within a very short time, Gage’s Atlantic supply lines fell prey to the privateer fleets of Newburyport, Salem, Beverly and Plymouth. According to reports from the Essex Gazette, Massachusetts privateers were far more successful in cutting off British supplies than their land-based counterparts. As early as September 9, 1775, the newspaper reported that “Last Saturday a privateer belonging to Newburyport carried into Portsmouth a schooner of forty-five tons, loaded with potatoes and turnips intended for the enemy in Boston.”[5]

Many of these privateers traveled in groups that varied in size from a few ships to over twenty. One such squadron from Newburyport consisted of twenty-five vessels and over 2,800 men. A second from the same town boasted thirty vessels.

Perhaps one of the most successful American supply interdictions during the Siege of Boston occurred on November 25, 1775 when the Lee, a privateer under the command of Capt. John Manly of Marblehead, captured the British vessel Nancy. According to a December 7, 1775 description, “Captain Manly, in the Lee, vessel of war, in the service of the United Colonies, carried into Cape Ann a large brig called the Nancy which he took off that place, bound from London to Boston, laden with about three hundred and fifty caldrons of coal; and a quantity of bale goods, taken by Captain Manly, was carried into Salem. She is about two hundred tons burthen, and is almost a new ship.” Of course, the Nancy was a military ordnance vessel from Woolwich, England, that carried no less than 2,000 muskets, 31 tons of musket shot, 30,000 round shot of “various sizes,” 100,000 musket flints, 11 mortar beds, and a 2,700-pound 13-inch mortar.[6]

A few weeks after the capture of the Nancy, the Essex Gazette announced Captain Manly had struck again. “Captain Manly has, within a few days past, taken another valuable prize, a sloop from Virginia bound for Boston, loaded with corn and oats; fitted out and sent by Lord Dunmore.”[7]

Towards the close of 1775, Massachusetts privateers were not only preventing much-needed supplies from reaching Boston but were also seizing enemy vessels in rapid succession. According to one newspaper report, “several vessels loaded with fuel, provisions of various kinds, &c, bound to Boston, have been carried into Salem and Beverly within a few days past.”[8] By mid-December, reports of successful captures by Massachusetts privateers were pouring into the colonies.[9] As Benjamin Hichborn noted to John Adams, “Our privateers have made so many Captures that, it is impossible for me to be particular, most of those from Europe I am informed have considerable quantities of Coal in them.”[10] Likewise, James Warren, president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, wrote about the success of privateers against British supply lines. “Several Prizes have been taken in the week past, & among the rest a fine Ship from London, with coal, Porter Cheese Live Hoggs &c &c and a large Brigt [brigantine] from Antigua with Rum Sugar &c all the Country are now Engaged in prepareing to make salt Petre fixing Privateers, or Reinforceing the army.”[11]

The activities of the Massachusetts privateers did not go unnoticed by British military officials. The spy Benjamin Church warned General Gage that “unless some plan of Accommodation takes Place immediately their [harbors] will swarm with Privateers.”[12] Maj.Gen. William Howe openly complained about the interdiction efforts when he stated, “I am also concerned to observe the Uncertainty of defenceless Vessels getting into this Harbour is rendered more precarious by the Rebel Privateers infesting the bay, who can take advantage of many Inlets on the Coast, where His Majesty’s Ships cannot pursue them, and from whence they can safely avail themselves of any Opportunities that offer.”[13] Similarly, Admiral Graves wrote about the difficulty of protecting vital supply lines, “Notwithstanding the utmost Endeavors of the Cruizers to protect Vessels arriving with Supplies, the Rebels watch the opportunity of the Kings Ships and Vessels being off the Coast, slip out in light good going Vessels full of Men, seize a defenceless Merchant Ship and push immediately for the nearest Port the Wind will carry them to.”[14] Eventually, Commodore Marriot Arbuthnot, who oversaw the Royal Navy’s North American station at the outset of the war, was forced to concede the early success of the Massachusetts privateers. “I am sorry to inform their Lordships, that I have it from pretty good Authority that the Rebels have many Armed Vessels . . . I have great reason to believe their Orders are to interrupt the trade of this Country, by preventing them from sending lumber & other Necessary’s to the West Indies, or Great Britain, & particularly to stop all supplies for Boston.”[15]

Even as the British army was preparing to evacuate Boston, Massachusetts privateers were still harassing Crown shipping lanes. On March 6, 1776. “the Yankee Hero sent into Newburyport another prize, a fine brig of about two hundred tons burthen, laden with coal, cheese, &c, bound for White Haven, for the use of the ministerial butchers, under the command of General Howe, Governor of Boston. This is the fifth prize out of eight which sailed from the above port.”[16] A little over a week later, Massachusetts sailors successfully intercepted a pair of vessels that carried artillery, ammunition, food and necessary medical supplies.[17]

According to historian George Clark, over a period of five months between November 1775 and March 1776, the number of British vessels captured en route to Boston “amounted to thirty-one, their tonnage to 3,045 tons.”[18]A similar study conducted by James Richard Wils revealed that New England privateers seized £1,575,500 worth of ships and supplies during the first two years of the war.[19]

The introduction of privateering had the desired result. The British encountered increasing difficulty in provisioning its army in Boston. Moreover, with the capture of supply vessels destined for the British garrison, the Americans gained muskets, ammunition, and provisions for themselves, affording them the potential ability to launch a land assault on the city. Worse still for the British, the soldiers and people in Boston began to starve.

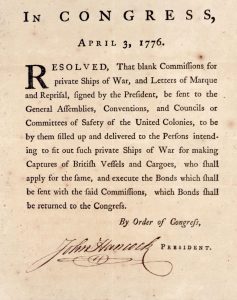

Both General Washington and rebel authorities recognized the important contributions of privateers towards the war effort. As a result, less than one week after the evacuation of Boston, the Continental Congress passed the Privateer Act of 1776. The act expanded privateer operations and authorized the vessels to “attack, subdue, and take all Ships and other Vessels belonging to the Inhabitants of Great-Britain, on the High Seas. . . . You may, by Force of Arms, attack, subdue, and take all Ships and other Vessels whatsoever carrying Soldiers, Arms, Gun-powder, Ammunition, Provisions, or any other contraband Goods, to any of the British Armies or Ships of War employed against these Colonies.”[20] In response, Massachusetts privateers, as well as those from other colonies, expanded their war efforts. According to the National Park Service, approximately 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers throughout the American colonies during the American Revolution. These ships were responsible for capturing or destroying over 600 British ships and inflicting approximately $18 million in damage, which translates to approximately $300 million today.[21]

[1]On May 7, 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety passed a resolution ordering selectmen from the towns located near Boston “to take effectual methods for the prevention of any Provisions being carried into the Town of Boston.” Minutes of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety 1775, in American Archives, Fourth Series, 6 vols., comp. Clarke M. St. Clair and Peter Force (Washington: U.S. Congress, 1837–46), 2: 753.

[2]Farm manager William Harris noted he was “very uneasy, the people from the Men of War frequently go to the Island to Buy fresh Provision, his own safety obliges him to sell to them, on the other Hand the Committee of Safety have threatened if he sells anything to the Army or Navy, that they will take all the Cattle from the Island, & our folks tell him they shall handle him rufly.” William Harris quoted in H. Prentiss to Oliver Wendell, May 12, 1775, Essex Institute Historical Collections(Salem: Essex Institute, 1877), 13: 181.

[3]The objective was to capture prizes and sell the vessels and cargo for profit to the ship’s owner, her officers and crew.

[4]According to a November 1775 resolution, Massachusetts privateers were authorized to “equip any vessel to sail on the seas, attack, take and bring into any port in this colony all vessels offending or employed by the enemy.” An Act For Encouraging The Fixing Out Of Armed Vessels To Defend The Sea-Coast Of America, And For Erecting A Court To Try And Condemn All Vessels That Shall Be Found Infesting The Same, Massachusetts General Court, November, 1775, State Library of Massachusetts, Acts and Resolves of the Massachusetts General Court (1692-1780), archives.lib.state.ma.us/handle/2452/117010.

[5]Salem Gazette, September 9, 1775, in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society(Boston, Massachusetts: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1885), 1: 21.

[9]For example on Christmas Day, a Plymouth based privateer successfully intercepted a supply sloop from New York. “On the 25th of December last [1775] was taken by a Plymouth privateer and carried in there a small sloop from New York, Moses Wyman, Master, laden with provisions fur the ministerial army in Boston, consisting of thirty-five fresh hogs, one hundred barrels of pork, fifty barrels fine New York pippins, twenty firkins hog’s feet, some quarters of beef, turkeys, &c., &c.” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 21.

[10]Benjamin Hichborn to John Adams, December 10, 1775, inJames Richard Wils, In Behalf of the Continent: Privateering and Irregular Naval Warfare in Early Revolutionary America(Greenville, NC: East Carolina University, 2012), 65-66.

[12]Benjamin Cowell, Spirit of ‘76 in Rhode Island, or Sketches of the Efforts of the Government and People in the War of the Revolution(Boston: A. J. Wright, 1850), 29.

[17]On March 14, 1776, “a transport brig of sixteen guns, laden with naval stores and provisions bound from Boston for the ministerial fleet at the southward was taken. A ship of two hundred and forty tons also captured by Captain Manly about this time was shipped with six double fortified four-pounders, two swivels, and three barrels of powder, while the cargo consisted of one hundred and seventy-five butts of porter, twelve packages of medicine with large quantities of coal, sourkrout, &c, besides a great number of packages for the officers in Boston. She also brought out sixty live hogs, but only one of them was alive when she was carried in.” Salem Gazette, March 14, 1776, in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 22.

[20]Instructions to the Commanders of Private Ships of Vessels of War, Which Shall Have Commissions or Letters of Marque and Reprisals, Authorizing Them to Make Captures of British Vessels and Cargoes(Philadelphia, 1776), www.sethkaller.com/item/1337-23701.99-John-Hancock-Signed-1776-Privateering-Act&from=5.

[21]John Frayler, “The American Revolution,” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, www.nps.gov/revwar/about_the_revolution/privateers.html.

10 Comments

Thanks for this article. It comes at the perfect time for me as I just finished reading about Boston’s deliverance in Rick Atkinson’s excellent book, The British Are Coming. This article added wonderful color.

Thanks Jon for the support! Atkinson’s Book is a great resource and very well written. I’m probably due to read it again soon!

Great article. In regards to the sentence, “Of course, the Nancy was a military ordnance vessel from Woolwich”, is that meant to convey that the original account tried to cover up that it was an ordinance ship? Thanks.

Hi Carl!

Great question. According to early newspaper reports, when the Nancy was captured and escorted into an Essex County harbor, Massachusetts officials either were unaware or did not comprehend the magnitude of their capture. I’ve seen newspaper reports from Newburyport, Salem and Providence acknowledging that a supply vessel was captured but it was unknown of what was found onboard. I suspect many thought the Nancy was merely carrying provisions. Of course, once the contents, including the weapon caches, was discovered, it became a major headline in Massachusetts newspapers for a few weeks.

So short answer is no, they were not covering up what they discovered. I guess I was just trying to quickly summarize the importance of the ship.

Hope all is well!

Enjoyable and thought-provoking article! Did the Continental Congress have to pay the privateer captain and crew for the Nancy’s captured muskets and other military stores?

Hi Gene!

What a great question! Unfortunately, I’m not 100% sure.

Traditionally, when an enemy vessel was captured by privateers, the ship was escorted into a safe harbor. A hearing (condemnation hearing) would be held before a judge to determine whether the ship’s owner lost his claim to the vessel. If the judgment was issued ordering condemnation, the ship was auctioned off. Likewise, everything on board the ship that wasn’t nailed down was auctioned off as well. I have a somewhat humorous account of a British captain bitterly complaining that after his captured vessel was escorted into Newburyport (MA), the residents didn’t even wait for the condemnation hearing and instead began to auction everything on the ship as soon as it was moored to a wharf!

As for the Nancy, it appears once officials realized what they had, the supplies were immediately sent to Washington and the American forces outside of Boston rather than be auctioned off.

I seem to remember seeing references to Captain Manly and his crew being compensated for the Nancy but can say for certain where I saw it or whether it was for the sale of the ship itself (not the supplies) or if the Massachusetts or Continental government compensated them.

Let me check and get back to you!

OK…so according to the Essex Journal And New Hampshire Packet, published in Newburyport, Massachusetts on Friday, March 1st, 1776 the Nancy was scheduled to be condemned on March 20, 1776. It appear that happened, so Manly and his crew would have shared the profits from the sale of the vessel itself. As for the captured supplies…still looking to see what the compensation was if anything.

Alex, thank you for further research and info!

I do know later in the war, governments received a sizeable portion of the proceeds from the captured ships. Perhaps, in this early instance, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts took the muskets and other military stores as its cut, supplied them to Washington, and left the ship and the rest of the cargo to the ship’s captain and crew.

Your article adds to a better understanding of the oft-neglected interactions between privateers and the supply of arms and military equipment to the Continental Army.

Always love reading an article on privateers in the Revolution. I’m a bit late to leave a comment now but I came up with this question only recently. You say that privateers sailed together in groups of several vessels. I’m wondering about two things:

1. Was traveling in groups for “safety in numbers”? in the event that they encounter a very powerful ship, say, a third rate British navy vessel? (not that I know the extent of Britain’s naval presence outside of Boston’s waters, just an assumption) I assume even the most powerful naval vessel would have trouble in an encounter with two dozen well-armed privateer vessels, assuming the vessel is patrolling alone.

2. A privateer’s main goal was to make profit off of plundering enemy vessels: but wouldn’t traveling in groups conflict with that goal? If I was a privateer, wouldn’t my crew and I benefit more from plundering a ship all to ourselves instead of me and three, six, or ten other privateer vessels plundering a single vessel, in which we would have to split up the prizes?

For those interested in seeing what the “Nancy” had aboard her when she left England, visit https://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw4.033_1059_1068/?sp=1 and the pages following (“George Washington Papers” at the Library of Congress). In seeing what the Americans inventoried after Capt. Manly and his crew captured her, visit the four pages of the “Papers of the Continental Congress” beginning at https://www.fold3.com/image/1/441973 (it’s a free portion of fold3). It would be interesting to compare the two lists–a project for some other time.

‘Twould appear from a number of letters that Washington started doling out the supplies taken on the “Nancy” within a couple of weeks.

Captured a couple times by the Royal Navy, Capt. Manly spent several months in Mill prison in England. He unsuccessfully attempted an escape more than once. Must have been quite the character.