With no actionable intelligence, General Washington had to guess where British Maj. Gen. William Howe was taking his army. So in July 1777, he led the Continental Army north from New Jersey into what was then a rough, dangerous, and little-known pass through New York’s Ramapo Mountains. He had guessed incorrectly, however, and they were soon racing south again. Two hundred and forty-two years later, one of the last vestiges of this frantic Revolutionary detour may fall to a bulldozer.

After wasting much of the spring of 1777 trying to lure Washington’s army out of the Watchung Mountains, General Howe moved his army out of New Jersey and back to Staten Island. The preceding twelve months included the battles of Long Island, Harlem Heights, White Plains, Trenton, Assunpink Creek, Princeton, and Short Hills, but Howe was now literally back where he had begun. Together, the eight battles had earned the British little more than possession of Manhattan.

In July, Howe’s soldiers began to board ships. This was big news, but not actionable intelligence. Washington needed to know where the enemy planned to go. Howe’s ships could take the Crown troops any place near navigable water. The Continentals, on the other hand, would have to race on foot to meet Howe’s Anglo-German army, planning their first movements on nothing more than an educated guess. This was an extreme disadvantage for the Americans. Washington reported to congressional President John Hancock, “The amazing advantage the Enemy derive from their Ships and the Command of the Water, keeps us in a State of constant perplexity and the most anxious conjecture.”[1]

Conjecture focused on two primary possibilities: Howe might move up the Hudson River and seize the Hudson Highlands, a strategic choke point on the river next to the site where the United States Military Academy was later built and sixty miles upriver from New York City. With Gen. John Burgoyne’s forces moving south from Canada, this maneuver would complete the British plan of achieving control of the critically important Hudson-Lake Champlain corridor. The other scenario was an attack on Philadelphia, the target Howe had seemed intent on taking through the spring. If the seat of Congress was in fact his target, a landing on the west bank of the Delaware River now seemed most likely.

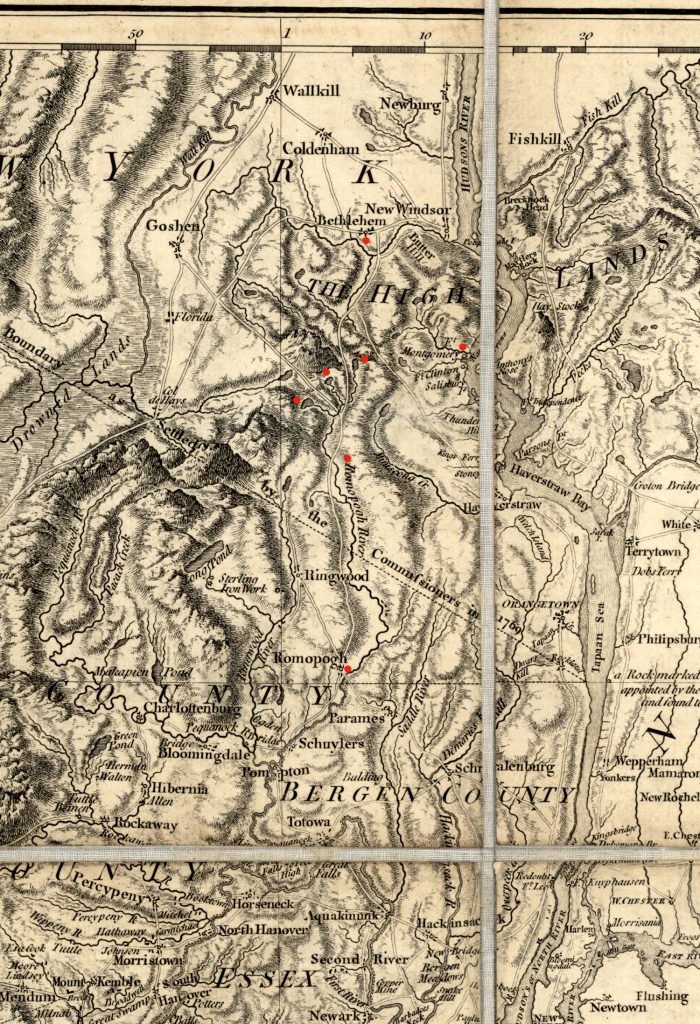

The American troops began to congregate at Morristown. When news arrived that General Burgoyne had taken Fort Ticonderoga, the Hudson Valley scenario suddenly seemed to be unfolding. American Gen. John Sullivan was sent racing north with an advance force. The rest of the army followed to Pompton Plains, where it was bogged down by rain, and then continued on to the “Clove.”[2]

The Clove—known also as the Ramapo Pass, the Ramapo Valley, Sidman’s Pass, Smith’s Clove, and other names—was a pass through New York’s Ramapo Mountains that followed the river of the same name. In the words of a local historian, the Clove “was of ample width and broad enough in the mid-valley to allow extensive tillage, but at two points—at Woodbury Falls within the northern mouth and at Ramapo within the southern—it narrowed to funnel-like defiles barely wide enough to allow the passage of both a road and a narrow waterway.” The name comes from the Dutch word kloof, which means “chasm” or “gap.” The Clove Road was the primary overland route from points south to the Highlands. The critical strategic importance of the Highlands made the pass an important military thoroughfare. Maj. Gen. Charles Lee—after declaring, “I am going into the Jerseys for the salvation of America,” led troops through the Clove in December of 1776 shortly before he was captured by the British. Reinforcements from Gen. Horatio Gates’ northern command also came through the Clove to join Washington before the Battle of Trenton.[3]

The route from Morristown to Pompton, and through the Clove, was fairly direct. From the northern end of the passage one could continue on toward Albany or hook east to the Highlands. For most purposes, the Hudson River was a better transportation artery, but the lower part of the river was now controlled by the enemy. Though newly important, the Clove Road was still a rough way to go. Over the years it had been progressively described as an “Indian path,” a “horse path,” and “very stony and narrow” road. As late as 1779, an American officer dramatically described the valley as “most villainous country, Rough, Rocky and a bad climate. Rattle snakes & Robbers are plenty. It was an infringement on the rights of the wild Beasts for man ever to enter this Clove, it ought to have remained as Nature certainly intended for it for the sole use of snakes, adders, & Beasts of prey.” Among those beasts of prey was a group of Loyalist outlaws known as Claudius Smith and the Cowboys, whose tactics approximated modern definitions of terrorism.[4]

The southern entrance to the pass was known as “Suffern’s Clove,” aligning with the name of a tavern that was open for business there. “Smith’s Clove” was the name for the northern defile and a name that was sometimes used to refer to the entire pass. There were seven taverns and houses available to travelers coming and going along the twenty-mile length of the Clove Road. The southernmost was Suffern’s Tavern. From Suffern’s, a north-bound traveler would encounter Sidman’s, Sloat’s, Galloway’s, June’s, Smith’s, and Earl’s taverns. They varied significantly in size and in the quality of their accommodations. Suffern’s sat at an important spot where roads converged to enter the Clove. Smith’s, near the north end, also offered quality accommodations. Earl’s was described as “a rather poor inn” and Galloway’s was nothing more than “an old log house.”[5]

The army set up camp near Suffern’s Clove on July 15, still wondering where Howe was going. It was unfamiliar territory for most of Washington’s men, some of whom mistook the name of it as “Sovereign’s Clove.” Morale was high. The army had been resupplied and the enemy had abandoned New Jersey.[6]

After five days, Washington received intelligence that Howe was indeed headed up the Hudson. He took the Continentals into the Clove. “We marched over a very difficult and rugged Road till Night,” he reported to Congress. Gen. William Maxwell’s New Jersey Brigade took the van and Gen. Peter Muhlenberg’s brigade of Virginians took the rear. They camped again around Galloway’s for two rainy days. Little is known about this place. Though contrary to local histories, it is plausible to think that Galloway’s was not a tavern at all but rather a private residence. Here, Washington slept in a bed with his aides de camp on the floor around him.[7]

On July 22, the army arrived at Smith’s Tavern, just eleven miles from the Hudson. New intelligence, however, contravened the earlier report: it was still unclear where Howe was going. Washington was forced to hedge. Lord Stirling’s brigade was already positioned on the east side of the Hudson at Peekskill. Two divisions under generals Adam Stephen and Benjamin Lincoln were sent west to the village of Chester, from where they could rush to Philadelphia or to the Hudson Highlands as events might warrant. Jonathan Clark, a captain in the 8th Virginia Regiment, noted in his always terse diary that he “march’d as far as Smith’s Tavern about eleven miles from the N[orth, or Hudson] River and turned towards Philadelphia, march’d thro Chester [New York] and encamped near ditto. Lay 13 miles from Smiths.”[8]

Definitive intelligence finally arrived: Howe had taken his seaborne army south on July 23. He tried to misdirect the Americans with false information, but Washington didn’t fall for it. On July 25, Captain Clark wrote that he, in Stephen’s Division, marched sixteen miles south past the village of Warwick, New York and on the following days into New Jersey: twenty miles to Andover Furnace, twenty-three miles to Hacketts Town, seventeen miles to Pittstown, and so on. Another soldier in Stephen’s Division, Sgt. William Grant of the 12th Virginia, described this as a “very hard and fatiguing” forced march. After he defected to the British in September, he claimed that during this movement they were “marching at the rate of thirty miles per day, which killed a number of the men. It was no uncommon thing for the rear guard to see 10 or 11 men dead on the road in one day occasioned by the insufferable heat and thirst; likewise in almost every town we marched through, their Churches were converted into hospitals.”[9]

The two armies finally clashed in a skirmish at Cooch’s Bridge on September 4 and in a major battle at Brandywine on September 11. Given the importance of holding the pass through the Ramapo Mountains, however, other troops were kept stationed at the Clove. Col. William Malcolm’s Additional Continental Regiment, most often under the actual command of Lt. Col. Aaron Burr, was stationed at Suffern’s in September. In his 1886 history of Rockland County, New York, Frank Bertangue Green summarized:[10]

The Ramapo valley, or Sidman’s Pass, was the great pathway from West Point and New Windsor to the country south of the Highlands, and was in almost constant use by some portions of the army from 1776 till the close of the war. Through its narrow defile Burgoyne’s army passed as prisoners, on their long march from New England to Virginia in the autumn of 1778. In June, 1779, it was again the camping place of the Continental Army, and was strongly intrenched at that time. The remains of the intrenchments are still visible, and the relics of its military occupation are not few.[11]

While the relics of the Clove’s military use may have been plentiful in 1886, that is no longer true. Of the seven taverns only two remain: Sloat’s and Sidman’s. Sloat’s stayed in the possession of the Sloat Family until 1905 and is still a private residence. Sidman’s Tavern is just a mile south of Sloat’s and is better known today as the Smith House. Parts of the house may be more than three hundred years old. Elements of a tavern built about 1714 were incorporated into the current structure by Stephen Sloat around 1753-1755. The Rockland County Historical Society believes that Gen. Lee, Gen. George Clinton, Gen. James Clinton, and other notable figures including Lord Jeffrey Amherst were guests at Sidman’s Tavern.[12]

The last residents of the Smith House were the Pierson Mapes family, who moved out two decades ago. In 2014, the Town of Ramapo approved the construction of a large apartment building on the property, to be known as the Ramapo Woodmont Apartments. The village of Sloatsburg fought the development, but lost. The woods that once concealed the house have been cut down and the deteriorating house now stands exposed. Notably, the house is not the only thing of historic value on the property. There is also a cemetery that dates to before the Revolution. It may contain military graves. The last unaltered stretch of the original Clove Road also runs by the house. The tree removal has, however, made the dirt road almost indistinguishable from the dirt around it. Woodmont Properties agreed in 2014 to give the house to Ramapo, but it is unclear if that will save it. The town has reportedly “been trying to reduce it’s [sic] historical property portfolio, leaving Woodmont in a sort of limbo about what to do with the Smith House/Sidman’s Tavern.” The developer has said it plans to preserve the cemetery and wants to erect a historic marker to memorialize the road.[13]

It seems that Sidman’s Tavern and the last preserved stretch of the road may soon be gone. Though Sloat’s Tavern would also remain, a preserved cemetery and a historic marker would be paltry reminders of the significant events that occurred along the Clove Road during the Revolutionary War.

[1]George Washington to John Hancock, July 25, 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-10-02-0402, accessed April 11, 2019.

[2]Octavius Pickering, The Life of Timothy Pickering (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1867), 1: 145-146; Jonathan Clark, Diary,Filson Historical Society manuscript collection, Louisville, KY, July 6, 1777; Michael C. Harris, Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle That Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777 (El Dorado Hills, Cal: Savas Beatie, 2014),63.

[3]Richard J. Koke, “Corridor Through the Mountains,” orangecountyhistoricalsociety.org/Koke_Part_1_Chapter_1.html, Part 2, Chapter 5, accessed April 14, 2019; “Sloatsburg’s Original Watering Hole,” Sloatsburg Village: Local News & Community Life, April 3, 2019, www.sloatsburgvillage.com/sloatsburgs-original-watering-hole, accessed April 7, 2019; William Heath, Health’s Memoirs of the American War Reprinted from the Original Edition of 1798, Rufus Rockwell Wilson, ed. (New York: A. Wessels Company, 1904), 105-108; Dominick Mazzagetti, Charles Lee: Self Before Country (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2013), 134-135; J. Bogart Suffern, “The Ramapo Valley During the American Revolution,” in Historical Society of Newburgh Bay and the Highlands Historical Papers, 13 (1906): 185-190.

[4]J. Wadsworth to Samuel B. Webb, June 17, 1779, in J. Watson Webb, ed., Reminiscences of Gen’l Samuel B. Webb of the Revolutionary Army (New York: Globe Stationery and Printing, 1882), 309; Koke, “Corridor Through the Mountains,” Part 1, Chapter 3; orangecountyhistoricalsociety.org/Koke_Part_1_Chapter_1.htmland orangecountyhistoricalsociety.org/Koke_Part_1_Chapter_3.html, accessed April 8, 2019; Charles Dewey, “Terror in the Ramapos,” Journal of the American Revolution, March 25, 2019, allthingsliberty.com/2019/03/terror-in-the-ramapos/.

[5]Koke, “Corridor Through the Mountains,” Part 1, Chapter 5.

[6]Jonathan Clark, Diary, July 15, 1777; Pickering, Life of Timothy Pickering, 147; Persifor Frazer to Polly Frazer, July 18, 1777 in Persifor Frazer, General Persifor Frazer: A Memoir Compiled Principally from His Own Papers by His Great-Grandson (Philadelphia: privately published, 1907), 164, quoted in Thomas J. McGuire, Philadelphia Campaign, (Mechanicsburg: Stackpole Books, 2006), 1: 78.

[7]General Orders, July 19, 1777; Washington to Hancock, July 25, 1777; Clark, Diary, July 20, 1777; Pickering, Life of Timothy Pickering,1: 147.

[8]Clark, Diary,July 23, 1777; Washington to Hancock, July 25, 1777.

[9]Clark, Diary, July 23-31, 1777; “Narrative of Sergeant William Grant,” in Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New-York; Procured in Holland, England and France, E.B. O’Callaghan, ed. (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1857), 728-734. While Grant’s narrative is generally correct, he appears to be exaggerating here, at least with regard to distances, and may have been under pressure to please his interrogators and to give detail he couldn’t accurately provide.

[10]Frank Bertangue Green, The History of Rockland County(New York: A.S. Barned & Co., 1886), 82.

[12]Sloat House, National Registry of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form, November 5, 1974, catalog.archives.gov/id/75321502, accessed April 14, 2019.

[13]“Sloatsburg’s Original Watering Hole;” “Where Sloatsburg Started,” Rockland County Historical Society, www.sloatsburgvillage.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Smith-House-Pamphlet-PDF.pdf, accessed April 14, 2019.

15 Comments

A great story. Thank you. I lived in Suffern for 12 years. I have hiked that area all my life. Very enlightening and informative.

Thanks for this story – very timely. Let’s hope this will not be “another one [that] bites the dust…. ”

There is a wonderful description in Chastellux’ “Travels” plus the road was also taken by Major Baumann and the artificers in August 1781. Coming from Newburgh they joined up with the rest of the CA at Pompton, which makes the road part of the Washington Rochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historic Trail (W3R-NHT or WaRo in NPS parlance) and described in detail for 1781 (with maps) in my W3R in NJ report. https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Tq0ZoCO7xOmQfsMSwgf70_2fQt_iZaDm

Am I correct in understanding that the development was approved by the town in 2014 but has not yet been built? If that is the case it seems like a long time between approval and start of construction. Could it be that the development is no longer economically feasible? Of course if true it does not help preserve the historic tavern.

Sad that we are disposing of our vital historical treasures with little thought to future generations. These are sites which can never be replaced. They should remain dear to the hearts of all citizens. Surely they should take precedence over apartments, banks, hotels, service stations, or pizza joints. Those are a dime a dozen. Historical sites are priceless. I hope for a favorable outcome for this one. It would be heartbreaking to see it lost.

Jim, thank you.N couldn’t have said this any better. To say it’s distressing would be an understatement.

Gabriel,

It is nice to see someone call attention to this. In the last talk I did, I mentioned all the taverns along the Ramapo Pass including the Sidman, Earl, and Sloat Taverns and a large portion of the Q&A was devoted to talking about them as well. Although the audience was local, many of them were unaware of the rich history held in these historic sites right in their own backyards. Many historians are now calling attention to tavern-life throughout the colonies, but very few sites remain as it is. Seeing another one go is beyond unfortunate. Thank you for the acknowledgment and the timely article.

Very interesting article. It is worth noting that the Ramapo route described was used by the Noble, Townsend and Co. to deliver the chain links forged at Sterling Lake to Captain Thomas Machin in New Windsor, to be floated from there down to West Point and stretched across the 1500 foot wide Hudson. The links were delivered by sledge and yoked oxen in March-April 1778.

Can you provide a source for this information?

An important piece of history not only for Sloatsburg but for the town of Ramapo and New York state. Hopefully, it will be saved and not just a marker.

I read this article with interest because my 5th Great-Grandfather, GARRETT MILLER who served in the Revolution and died in Provost Prison as a POW had land in the Smith’s Clove area. I feel that every effort needs to made to save and restore the house along with cemetery, find if there are any military burials so their legacy will not be forgotten. We can provide housing and places of business along with our heritage. These sites of Revolutionary War interest need be preserved for future generations

Steve Holland—would love to connect and talk; I live in the area where Garret had land.

In Dr. James Thacher’s diary, he writes, “Marched over the mountains and reached Carle’s Tavern in Smith’s Clove where we halted for 2 hours, then marched another 13 miles before stopping.” Could he have meant the Earl’s Tavern mentioned above?? If so, where exactly on the route was it?

It seem likely that this is a mistranscription of Earle’s Tavern. Richard J. Koke wrote:

Earl’s Tavern, half-a-mile north of Smith’s, stood on the west side of the Clove Road (Route 32) in Highland Mills, directly opposite the Revolutionary War road (now Park Avenue) that led eastward through the mountains to the Forest of Dean and West Point. The proprietor was undoubtedly the elder John Earl, a prominent local landowner who was appointed a fence viewer for Woodbury Clove in 1765. In 1779 the Orange County outlaw Claudius Smith was indicted for a burglary “at the house of John Earle,” for which, among other crimes, he was executed at Goshen. In 1780, the Marquis de Chastellux, erroneously identifying it as “Herns,” called it “a rather poor inn.”

I just came across this article tonight. Can the author (or anyone else) provide an update on the legal status of the actual former tavern building itself and surrounding property which are seriously threatened by the planned construction of an apartment complex? What is the political situation like? Is there any political faction, group or individual(s) in elected or appointed office that opposed this development plan? Here in Connecticut, I worked with a handful of other local residents and a former museum curator and professional historian to overturn a town resident’s plan to basically destroy a 1700s landmark property so he could build a brand new Mcmansion on the historic site. I and others basically “landed on” the town for approving his plan to destroy the historic property and, although small in number, we all showed up at a town hearing and spoke persuasively against the decision in question. As news coverage of our small group grew, so did our numbers. More people spoke out and the in-state coverage grew. The owner was a financial advisor who was aghast at the bad publicity he was receiving in town which I am sure was not beneficial to his business. Instead of getting more clients, he turned a bunch of people off. Eventually, he gave up and sold the 1700s era house (former home of a Revolutionary War soldier). You need to build a coalition of politicians, historians, history buffs, historic preservation folks, lawyers (like me) etc. and get the press to cover your group’s efforts. Get some press coverage! Picket outside of the property or at town hall! SHOW UP at public hearings in town or at the town council’s “open mic” night where citizens can address town officials on any subject they choose. My question: Is it already too late? Does the house/tavern still stand?…

The latest on this is that the apartment complex is complete and people have moved in. The developer has, according to a video, committed to working with local stakeholders to preserve and restore the house. They previously committed to preserving the cemetery. The dirt road, which could be considered to have been obliterated as soon as they cut down the trees round it, may be lost. Someone local may be able to give a better update. See this report and the embedded video: https://www.sloatsburgvillage.com/move-in-day-at-woodmont-hills-ramapo-shines-a-light-on-historic-preservation/