John Paul Jones has earned enduring fame in American history for his sailing and fighting exploits during the American Revolution. His influence on the war, however, went far beyond his alleged immortal words while engaging the HMS Serapis with his vessel, the Bonhomme Richard. For a period in 1778, the mere mention of his name caused terror within the very consciousness of the British nation. Jones’s successful employment of psychological warfare influenced many future commanders. He calculated that as Great Britain became more and more overextended by a global conflict there would be fewer military resources to defend the home island.

For the first three years of the American Revolution, as James Thomson’s 1740 patriotic poem proclaimed, Britannia literally did rule the waves with its vast Royal Navy. The British Isles felt firmly secure behind their fleet’s “wood walls” of protection. The last time any foreign power had mounted a victorious amphibious landing on English soil was over a century before. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War, in 1667 the Dutch raided and burned the fortifications at the Southeastern Kentish port of Sheerness on the river Medway, including the humiliating capture of the mighty British eighty-gun warship Royal Charles. In 1778 a daring young transplanted Scotsman named John Paul Jones wanted to carry America’s struggling war effort to the very doorstep of King George III. Jones’s vision for innovative use of the fledgling American navy won the endorsement of influential members of the Continental Congress. After meeting Jones in France, John Adams recorded in his diary that,

This is the most ambitious and intriguing Officer in the American Navy. Jones has Art, and Secrecy, and aspires very high. You see the Character of the Man in his uniform, and that of his officers and Marines, variant from the Uniforms established by Congress. Golden Button holes, for himself—two Epauletts—Marines in red and white instead of Green. Excentricities and Irregularities are to be expected from him—they are all his Character, they are visible in his Eyes. His Voice is soft and still and small, his Eye has keenness, and Wildness and Softness in it.[1]

Jones had developed a clever strategy that he believed would prove that the British homeland was not impregnable. In a later memorandum to the American Plenipotentiaries and to the French Minister of Marine, Antoine de Sartine, he outlined his ongoing “Plans for expeditions,” a template for future actions that would carry America’s war effort directly to the shore of its enemy. One proposal was that, “Three fast frigates with tenders might burn Whitehaven and its fleet, rendering it nearly impossible to supply Ireland with coal next winter.” He believed he could bring “inconceivable panic in England. It would convince the world of her vulnerability, and hurt her public credit.” Benjamin Franklin, who was well aware of unrest in Ireland, fully agreed with Jones that a disruption of its coal supply would further increase problems with the Crown’s administration of Ireland. Franklin also concurred that such a raid would cause Britain to divert military power to protect the homeland; however, as a cunning politician, Franklin no doubt understood that it would not be a good idea to be openly associated with an act that in modern terminology might be considered terrorism. Nevertheless, Jones proposed at least half a dozen similar plans and projects; but the 1778 Whitehaven proposal was the one brought to fruition.[2]

Jones, among others, realized the impossibility of America building large warships to confront the Royal Navy.[3] He placed his conclusions in an April 1776 letter to America’s commissioners in France, writing, “We cannot yet Fight their Navy, as their numbers and Force is far Superiour to ours,” and attempts to face them on their own terms would be ruinous. He felt that it would be America’s “most natural Province to surprize their defenceless places and thereby divide their attention and draw it off from our Coasts.”[4]

Jones was not a novice at taking offensive measures to bring the war to the doorstep of the British. On September 22, 1776, as the captain of the twelve-gun sloop-of-war Providence, Jones raided the Nova Scotian town of Canso and its surrounding fishing villages. His attack destroyed fifteen vessels and considerable property on shore. He returned later in November, striking the communities of Petit-de-Grat and Arichat on Isle Madame. On this occasion, nine ships were taken and their captured crews were used to man the seized prizes. Jones’s repeated raids vastly contributed to the devastation of the Nova Scotian maritime economy. As an example, Jones obliterated the fishing storehouses and other supporting structures owned by John Robin on Jerseyman’s Island in Arichat Harbor. Robin did not feel it was safe to take a chance to re-establish his business until the end of the war. Jones reported that, “The fishery at Canso and Madame is effectively destroyed.” He concluded that if the raid had gone further with additional devastation and imprisonment of sailors, “I should have stood chargeable with inhumanity.”[5] Other continual American threats to this area cost the British tens of thousands of pounds and forced them to deploy urgently-needed warships and troops. Jones’s raids essentially shattered the Nova Scotian fishing industry and caused an economic panic that was felt in Great Britain. Hitting the enemy on their own loyal territory was not merely an opportunity to seek revenge for destroying American New England seaports, it was policy Jones followed in order to have deep commercial and military consequences for the British, which eventually and significantly aided America’s military efforts.[6]

Jones may have learned from French governmental sources of an official British policy to burn and destroy American seaports. In March 1778, the British Secretary of State for the American Colonies, Lord George Germain, ordered Gen. Sir Henry Clinton, commanding in New York, “to endeavor without delay to bring Mr. Washington to a general action. And, if that could not be accomplished, to give up every idea of offensive operation within land and employ the troops under my command only in desultory expeditions in conjunction with the King’s ships of war, for the purposes of attacking the rebel seaports between New York and Nova Scotia and seizing or destroying all their vessels, wharves, docks, and naval and military stores along the coast.”[7] Jones’s proposed a plan of retribution consisting of: raiding an English mainland port in retaliation for the British burning of Norfolk, Virginia, Charlestown and Falmouth, Massachusetts, and Fairfield, Connecticut; destruction of commercial and military shipping; and seizure of individuals highly regarded and politically connected as hostages to compel the British government to exchange captured American sailors languishing in British captivity. In a letter to Continental Congressman Robert Morris, Jones was particularly incensed with the treatment of imprisoned American Sailors in “English dungeons, not as Prisoners of War, but under the complicated appellations of Traitor, Pirates and Felons whose necks they wish to destine to the cord, and whose hearts they wish to destine to the flames.”[8]

The plan had the backing of many influential men who fully agreed with this concept of warfare. Morris had told Jones, “It has always been clear to me that our infant Fleet cannot protect our own coasts & that the only effectual relief it can afford us is to attack the Enemies’ defenseless places & thereby oblige them to Station more of their Ships in their own Countries or to keep them employed in following ours and either way we are relieved so far as they do it.”[9]

Early in the war, members of the Continental Congress’s Marine Committee had refrained from ordering total warfare on the English populace; but as the brutality of the fighting increased, it became apparent that within this struggle all previous restrictions were off and Jones’s views fully prevailed. In a never-sent draft, it was urged that “open and hostile operations” be utilized on any of “the Towns of Great Britain or the West Indies.” These targets, which included the important ports of “London, Bristol, Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh,” were “to be considered as the first objects of national retaliating resentment.” In particular, the war should be carried to, “London, the Seat of royal Residence and vindictive rage and the quarter from which have issued orders for the conflagrations which have by the Enemy been lighted up in these United States.”[10]

Jones had at his disposal the American-built sloop-of-war USS Ranger. Jones possessed tremendous talents as an ocean-going sailor and acquired detailed technical knowledge of each vessel he commanded, and went to extraordinary efforts to enhance the effectiveness of the Ranger. For example, he determined the warship was too lightly constructed to successfully bear its original twenty cannon and decreased the armament to a more efficient eighteen six-pound guns. This new distribution of weapons lowered the vessel’s center of gravity. Jones also believed the Ranger was over-sparred and had the sails shortened and recut, and added thirty tons of lead ballast. During the ship’s refit in the French port of Brest, the crew scraped and cleaned the Ranger’s bottom to maximize its speed and handling. Jones’s accomplishments as an effective warship commander owed as much to his pre-campaign preparations as to his talented and decisive tactical judgements made during the heat of battle.[11]

On April 10, Jones and his crew of the Ranger sailed from Brest for the Irish Sea and in quick succession seized many British merchantmen, culminating on April 18 with a minor engagement against the revenue wherry Hussar. The Hussar managed to escape, and the boat’s captain reported that the Ranger’s commanding officer was“dressed in white with a large Hat Cocked” which puzzled him as white was neither the dress of the French Navy nor that of any merchantman, but of the French Army.[12] It is possible that Jones dressed in this manner for mere bravado.

Jones was prepared to teach Britannia a major lesson, “with every intention to make a descent at Whitehaven,” including “everything in readiness to land” accompanied by “a party of volunteers.” But, “the unpredictability of nature” delayed the attack as “the Wind greatly increased” along with “the Sea” making it “impossible to effect a landing.”[13]

That soon changed. A British report from Whitehaven on April 23 said, “The Ship Ranger an American privateer, John Paul Jones Master Carrying Eighteen Six pounders pierced for 20 – 150 men landed 30 Men at this Port between two and three o’clock this Morning with an intent to set fire to the Shipping.”[14] Jones’s account was that with the advent of “fair Weather” on April 22,

At Midnight I left the Ship with two boats and 31 Volunteers: When we reached the outer Peir the day began to dawn; I would not however abandon my Enterprize, but dispatched One boat under the direction of Mr. Hill and Lieutenant with the necessary combustables to set fire to the Shipping on the North side of the Harbour; while I went with the other party to attempt the South side. I was successful in scaling the Walls and Spiking all of the canon on the first Fort; finding the Sentinals shut up in the Guard house they were secured without being hurted; having fixed Sentinals, I now took with me one Many only (Mr. Green) and spiked up all the Cannon on the Southern Fort, distant from the other a Quarter of a Mile.

On my return from this Business, I naturally expected to see the Fire of the Ships on the North side as well as to find my own party with everything in readiness to set Fire to the Shipping on the South. Instead of this I found the Boat under the direction of Mr. Hill and Lt. Wallingford returned, and the party in some confusion, their Light having burnt out at the instant when it became necessary. By the strangest Fatallity my own Party were in the same situation, the Candles being all burnt out: The day too came on apace yet I by no means retreat while my hopes of Success remained. Having again placed Sentinals a light was obtained at a House disjoined from the Town; and Fire was kindled in the Steerage of a large Ship [a collier named the Thompson] which was surrounded by at least an Hundred and Fifty others, chiefly from Two to Four hundred Tons burthen, and laying side by side aground, unsurrounded by the Water.[15]

Realizing the element of surprise was gone as Whitehaven’s “Inhabitants began to appear in Thousands and Individuals ran hastily towards us,” Jones “stood between them and the Ship on Fire with a pistol in my hand and ordered them to retire which they did with precipitation”[16] He later learned that the outpouring of people into the streets was due to a member of his crew. The sailor was an Irishman and former British soldier named David Freeman who had originally enlisted under the sobriquet of David Smith with the hope of returning to the British Isles by seizing any opportunity that might present itself. He had turned traitor and aroused the seaport as a sort of horseless Paul Revere, warning the residents house-to-house to arise and save their ships. The townspeople and the crews of the harbor’s anchored ships poured into Whitehaven’s streets and advanced towards Jones’s position on the quay armed with everything from muskets to carving knives.

Jones frantically urged his men to join him in torching as many stranded British vessels as possible, with the hope that their closeness and highly flammable combinations of wood, tar, and canvas would cause a vast conflagration. Some of his crew appeared listless or staggered about as his commands seemed to go unheeded or even uncomprehended. Apparently, some of the sailors had discovered a nearby tavern and appropriated its inventory of ale and whiskey for their personal consumption. These rebellious sailors had even planned to abandon their captain on Whitehaven’s quay and proceed back to the ship. Fortunately, Swedish volunteer Lt. Jean Meijer, the one officer who had consistently proven his loyalty to Jones during the cruise, prevented this action by wisely posting a trustworthy armed midshipman to guard the Ranger’s small boats.

As the greatly outnumbered Americans backed into their boats, Jones continued to indicate he would shoot if Whitehaven’s inhabitants did not withdraw. As insurance, he had seized several local citizens as hostages, but all but three were released once the small boats were underway back to the Ranger. The freed garrison and the townspeople tried to halt Jones, but soon discovered their cannon were useless because of his previous sabotage. After much difficulty, a few cannon were repaired and rearmed, but their fire went wild and fell harmlessly into the harbor. As a mock salute, Jones and his men fired a swivel gun and pistols into the air. By half past six, the action was over and all were safely back onboard the Ranger.

The next day Jones tried another facet of his strategy, attempting to kidnap a person of consequence. This effort was even less successful than the Whitehaven raid, even though he did manage to get into the home of a Member of Parliament.

The consequences of Jones’s actions went much farther than the burning of a single ship, the humiliation inflicted on the town’s garrison by locking them in their own guardhouse, or the spiking some artillery. Jones wanted to bring the war home to the English and he accomplished this far beyond his expectations. His actions created a panic in the British Isles. As word spread throughout the kingdom, troops were summoned to protect Great Britain’s seaports and coastal towns against future retribution by Jones. For example, the Isle of Man’s Lt. Gov. Richard Dawson summoned the local Manx Fencibles, requested gentlemen to volunteer to serve, and required these resident forces to provide a twenty-man guard to protect his official residence every evening until further notice.[17] For Whitehaven itself, the spirited Penrith Fencibles were immediately dispatched and arrived in the seaport the day following Jones’s assault.[18] Two local justices of the peace reported that “There are now three Companies of Militia marched into the Town, and a Watch of Seamen established for Security of the Harbour; so that such attempts will not be easily carried into execution for the future.”[19] The citizens of Whitehaven, along with many other communities, petitioned the government “to order such protection to this place”[20] A Whitehaven resident wrote that, “We are all in a bustle here, from the late insolate attack of the provincial privateer’s men. I hope it will rouse us all from our lethargy.”[21]

Eventually, troops were garrisoned at almost every potential target in Great Britain that might tempt Jones. Although these were militia and fencibles whose purpose was to defend the homeland anyway, recruiting and sustaining these numerous defense forces further strained Britain’s already thinly deployed military forces throughout the globe. Additionally, there were major expenditures of public funds for almost every seaport and coastal community as an intense rebuilding and strengthening campaign of previously neglected defenses was implemented. Throughout the Kingdom, rumors spread that Jones would make another cruise. There was high anxiety that another such “visit” might occur in the Clyde to disrupt vital shipping with Greenock and the anchorages of the upper Firth as a prime target. At enormous governmental expense, coastal batteries were placed at Greenlock (Fort Jarvis), at the Tan between the two Cumbraes in order to defend the Auchenharvie coalfield from potential naval bombardment. These valuable military assets waited for additional raids and a possible invasion that would never come.[22]

Among the general populace, the concept that an “Englishman’s home” could be violated caused irrational thinking and feverish horror. The American “rebellion” had been a conflict out-of-sight and in some ways out-of-mind, but when shipping could be attacked in home waters, unprotected ports raided, warships defeated off of the coastlines, and citizens put in danger of capture in their very homes, the war now became a completely different matter. People living on the coast prepared to remove their valuables to locations of relative safety and banks had their gold assets transferred further inland for protection. Wagonloads of personal and business treasures, moved from coastal areas, restricted the availability of valuable resources, triggered widespread confusion, and caused great expense to the nation.

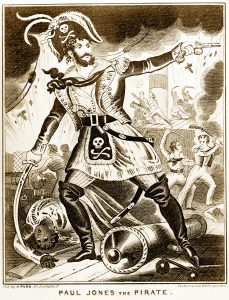

The overall apprehension was that the invasion at Whitehaven could occur at any coastal community and the next raider, almost positively, would not be hindered by an inept and mutinous crew. Printed colored chapbooks listing Jones’s depredations portrayed him as a bloody pirate armed to the teeth, further fanning the flames of fear. Parents terrified their children with the mention of his name as Jones was immortalized in songs, replacing the infamous Captain Kidd as the foremost buccaneer in their history. To these people, Jones was well-qualified to bear the title of “pirate” as he commanded a vessel disguised as a merchantman, made unexpected and secretive midnight attacks on ships and seaports, and in their eyes had a cold-blooded ruthlessness reminiscent of the savage Vikings immortalized in literature.[23] The general panic grew to such a point of ridiculousness that the press satirized it. One of their favorite jests was that the faculty of an Edinburgh medical school had moved completely into the town to attempt to restore the citizens to rationality and composure.[24]

The Whitehaven Raid hit Britain at its inner core, the empire’s economy. Jones had predicted that this project “would convince the world of her vulnerability, and her public credit.”[25] Almost immediately following the attack, the cost of war-risk insurance carried by private underwriters and not by the government rose to unprecedented levels. Beforehand, insurance underwriters had calculated that their risk started only when an indemnified vessel departed from home waters and ended when she returned to them. Now their shocking realization was that ships were in jeopardy when docked at the wharves in British ports, which caused them to quickly revise all of their rates abruptly higher. For example, the premium on a cargo to Ireland jumped from one-and-a-half percent of the cargo’s value to five percent. This alone cost British merchants more than the value of Jones’s destruction in Whitehaven. In addition, there was an instant interruption of business and trade as defensive measures for merchant ships, such armaments and convoying, were developed and implemented.[26]

Jones himself was distressed that his raid had not caused more destruction to the seaport where he had spent some of his formative pre-teenage years before immigrating to America.[27] He informed the American commissioners in France that his men landed “at Whitehaven and burned shipping; if we could have arrived earlier we should have destroyed the town, but we did show the enemy that what they have done in America can happen to them.”[28] Jones did admit he “was pleased that in this business we neither killed nor wounded any person.” He further believed that, “What was done however is sufficient to shew that not all their boasted Navy can protect their own Coasts—and the Scenes of distress which they have occasioned in America may be soon brought home to their own door.”[29]

Once the news reached America, the destruction was exaggerated as Jones’s exploits spread throughout the states. Congressman Elias Boudinot wrote to his wife that once the Ranger’s marines and sailors landed in Whitehaven, they “burned all the Ships in the Harbour, and spiked up about 30 Cannon in the fort & came off.”[30] Also in Congress, Richard Henry Lee continued the embellishment: “He landed at Whitehaven & fired the shipping in the Harbour, and did them other damage, where he also spiked 30 or 40 pieces of cannon.”[31] American newspapers repeated British news reports on the Ranger’s escapades, saying that as a “large column of smoke has been seen on the Scotch shore, this afternoon, it is feared she has done some mischief there.”[32] In actuality, a preliminary report to the British Admiralty confirmed Jones’s original assessment that “One ship was in a blaze, and as the Harbor was then dry, it might soon have spread and burnt the whole which are numerous but providentialy it was got the better of by about Six and no other damage happened but to this Single Ship.”[33]

As the news spread across Britain, newspaper accounts played into Jones’s hands as they heightened the feelings of dread and panic amongst the populace. Whitehaven’s Cumberland Chronicle presented quite a different view than the heroics of Jones’s later biographies and American naval histories. The newspaper told of a half-drunken rabble of ill-disciplined pirates who headed for the town’s alehouses instead of accomplishing their mission. There was no reluctant recognition of Jones’s bravery as he stood alone on the pier, armed only with a pistol, to protect the retreat of his men. Instead, he was remembered as a gangly youth who was found around the local taverns with a discernible talent for quarreling and insubordination. It was mentioned that he previously “went by the name of John Paul” and “was found guilty” in a London court for the murder of a ship’s carpenter while he was “the Master of a vessel, called the John,” but “made his escape” from justice to America. The editor bitterly continued that, “Every possible means is now put in practice to secure this harbor from future attempts of such daring wretches who having lost all feeling for their native country scruple not, under the sanction of a Congress commission to sharpen the sword of America in order to lacerate the bowels of their fellow countrymen.”

The article also published a copy of an affidavit by David Freeman, which was reprinted by many other newspapers, attesting to Jones’s mission to destroy Whitehaven’s shipping. Later, as Jones enhanced his perceived nefarious reputation, the Cumberland Chronicle would carry a front-page headline in the largest type in their possession: “Unparalleled Imprudence!”[34] Newspapers also contributed to the public’s general nervousness, occasionally to the point of hysteria, with accounts, real or concocted, of American spies throughout Great Britain. It is inconceivable how the Continental Congress, with little funds at its command, could have set up a spy or sabotage network as terrifying as was intimated by the press.

On a worldwide perspective, the Whitehaven raid, the subsequent failed attempt to capture a nobleman, and the overwhelming naval defeat of the fourteen-gun Drake off Carrickfergus within Irish home waters, gave the impression of negligence and unpreparedness on all levels by the Royal Navy. If this was true, then the Dutch nation might have an opportunity if they allied with the Americans and the French. It is entirely possible that Jones’s against-all-odds victories, albeit small in scale, helped bring the Dutch into the war.[35]

Historically, one of the raid’s other repercussions was the effect it had on British politics and the government of Lord North. Up until now, little public attention was paid to the anti-war views of Edmund Burke, William Pitt, Charles Fox and other liberals who had asserted the conflict was unwarranted and pointless; although the very spirit of the British constitution was on their side, their opinions had been quietly disregarded. A letter to the London Courant, published more than eighteen months after Whitehaven, said that Jones “hath stripped you [Lord North] naked, and driven you from every subterfuge, and exposed your negligence and incapacity, more generally, if possible, than they were before exposed.” If North and his government could not defend “our coasts from the long-continued depredations of a daring free-booter,” how could they “be fit to direct the naval force of this nation against the united efforts of the House of Bourbon.”[36] Now many Englishmen thought that self-preservation required serious attention. The viewpoint spread that if the American war was unjust from its beginning, it was now menacing enough to develop to become extremely dangerous to the home-front. The newspapers reported that an unjust war was bad, but if it threatened to bring retaliations to Great Britain’s shores it was more than dangerous, it was insufferable.[37]

The shadow of Jones’s landing on English soil and the threat of future expeditions kept the British populace in a heightened state of worry and alarm into the next year. Their fears were realized when, in August 1779, a combined Franco-Spanish fleet of approximately sixty-six warships anchored off of Plymouth with the aim of invasion. This time the British were better prepared and their adversaries, because of inept scouting, had no idea of the British channel fleet’s whereabouts. As civilians on the coast relocated inland, the various militias took to arms. Plymouth dockyard workers were furnished with weapons, and tin-miners from Cornwall marched by the thousands to offer support. The Admiralty sent orders for the British naval forces anchored at the Downs and the Nore to block the eastern end of the Channel. To further confuse the enemy, all helpful navigational aids were removed and all horses were taken inward from the coast to prevent their seizure. In addition, naval officers were posted in high places, such as Cornwall’s Maker Church, to monitor the enemy fleet and issue warning if necessary. In the end, the Franco-Spanish expedition achieved nothing because they neglected to take proper scouting measures and never obtained any pilots familiar with England’s south coast.[38]

In September 1779, Jones’s fame and persona grew exponentially with the epic engagement and subsequent victory over the forty-four-gun frigate HMS Serapis off of Britain’s Flamborough Head; characterized by historians as “one of the most desperate sea-fights in naval history involving an American vessel during the American Revolution.”[39] The tangible effects of Jones’s exploits continued to receive notoriety and reached farther than anyone could ever have hoped. Ultimately, during the eighteenth century, John Paul Jones proved to be one of the most formidable opponents England faced on the high seas, due to his extraordinary foresight, experience with the English coastline, and unparalleled fighting abilities; however, what sets him apart from other American naval commanders was his concept of attacking the British mind rather than their navy. The psychological shockwave Jones dispensed to the British Empire, and the repeat performance by him the following year, was tremendous. The overall destruction Jones caused to the Royal Navy was insignificant compared to the immense harm he exacted upon Great Britain’s will to fight.

[1]L.H. Butterfield, ed.. Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, May 13, 1779, Series 1 (Cambridge: The Belknap Press, 1962-66), 2: 370-371.

[2]John Paul Jones, “Memorandum, July 4-5, 1778,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, Claude A. Lopez et al., eds. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1959 – 2014), 27: 45.

[3]Jonathan Feld, John Paul Jones’ Locker: The Mutinous Men of the Continental Ship Ranger and the Confinement of Lieutenant Thomas Simpson (Washington: Naval History and Heritage Command, 2017), 13-14.

[4]“John Paul Jones to the American Commissioners, December 5, 1777,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 5: 248.

[5]“John Paul Jones to Esek Hopkins, September 30, 1776,” Mrs. Reginald de Koven, The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), 1: 116.

[6]Raid on Canso. www/revolvy.com/page/Raid-on-Canson-%281776%29, accessed January 16, 2019.

[7]William B. Wilcox, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954), 87.

[8]“John Paul Jones to Robert Morris, December 11, 1777,” de Koven, The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones, 1: 237.

[9]“Marine Committee to John Paul Jones, February 5, 1777,” Letters of Delegates to Congress 1774-1783, Paul H. Smith, et al, eds. (Washington: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 6: 222.

[10]“From the Marine Committee to John Paul Jones: Proposed Letter, July 19, 1779,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 30: 115-116; Franklin had previously ordered Jones to desist from destroying unprotected communities, although he was permitted to do so if ransom was declined and if he provided satisfactory warning for the sick, aged, women, and children for evacuation.

[11]E. Gordon Bowen-Hassell, Dennis M. Conrad and Mark L. Hayes, Sea Raiders of the American Revolution: The Continental Navy if European Waters (Washington: Naval Historical Center, 2003), 58-59.

[12]Samuel Eliot Morison, John Paul Jones: A Sailor’s Biography (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1959), 135-137.

[13]“To American Commissioners, May 27, 1778,” John Paul Jones and the Ranger, Joseph G. Sawtelle, ed. (Portsmouth, NH: Peter E. Randall, 1994), 160.

[14]“Port Captain John Botterell, R.N., To Philip Stephens, Secretary of The Lords Commissioners Of The Admiralty, April 23, 1778,” Michael J. Crawford, et. al.,eds., Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington: Naval History and Heritage Command, 1962-), 12: 592.

[15]“John Paul Jones to the Commissioners, May 27, 1778,” Papers of John Adams, Robert J. Taylor, ed, (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1977-), 6: 161-162.

[17]Samuel Eliot Morison, John Paul Jones: A Sailor’s Biography (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1959), 142.

[18]J. Bennett Nolan, “A British Editor Reports the Revolution,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 80 (1956): 109.

[19]“Sequel Of The Proceedings of Captain Paul Jones And His Crew at Whitehaven—Henry Ellison and William Brownrigg to Earl of Suffolk, April 24, 1778, Naval Documents, 12: 597.

[20]“Principal Inhabitants of Whitehaven, England to Earl of Suffolk, April 28, 1778,” Ibid, 12: 592.

[21]“Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, May 1, 1778,” Don C. Seitz, Paul Jones: His Exploits in English Seas During 1778-1780 (New York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1917), 11.

[22]Gerald Johnson, The First Captain: The Story of John Paul Jones (New York: Cowards-McCann, Inc., 1947), 203; Eric J. Graham, The Shipping Trade of Ayrshire 1689-1791 (Darvel, Ayrshire: Walker & Connell ltd, 1991), 32.

[23]de Koven, The Life and Letters of John Paul Jones, 1: 291-293.

[24]Johnson, First Captain, 203.

[25]“Memorandum,” The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, 27: 45.

[27]British estimates ran from 250 to 1250 pounds. Morison, Jones, 142.

[28]“John Paul Jones to the American Commissioners, May 27, 1778,” Papers of Benjamin Franklin,26: 535.

[29]“Jones to the Commissioners, May 28, 1778,” Papers of John Adams, 6: 162-163.

[30]“Elias Boudinot to Hannah Boudinot, July 14, 1778.” Smith, Letters, 10: 276.

[31]“Richard Henry Lee to Francis Lightfoot Lee, July 12, 1778,” Ibid, 267.

[32]The Pennsylvania Evening Post, July 28, 1778.

[33]“Botterell to Stephens,” Naval Documents, 12: 592.

[34]Cumberland Chronicle, April 25, 1778, Nolan, “A British Editor,” 109-110.

[35]Johnson, First Captain, 200.

[36]“London Courant, November 26, 1779”. Troy Bickham, Making Headlines: The American Revolution as Seen through the British Press (DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2009), 129.

One thought on “A Chink in Britain’s Armor: John Paul Jones’s 1778 Raid on Whitehaven”

Jones most likely wanted to avenge the burning of Kingston, NY, as well as other Colonial coastal towns. Morrison’s book.