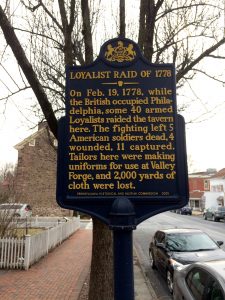

The small village of Newtown played a noteworthy role during the American Revolution from the time when General Washington’s army retreated in 1776 across New Jersey into Pennsylvania through the British occupation of American capital of Philadelphia until mid-1778. This was due to its geographical location in Bucks County, having been since 1726 the seat of justice. With a population of nearly four hundred, it was the site of the county’s courthouse and jail. The actual violent physical aspect of the war did not strike this community until February 1778 when Loyalist units attacked, causing twice the number of American casualties that Washington’s forces suffered at Trenton a little more than a year previously.

Following the 1777 British campaign to seize the American capital of Philadelphia, Gen. Sir William Howe and the Crown’s forces settled into a relatively comfortable occupation of the largest English-speaking city in North America, as opposed to Washington’s suffering forces encamped around their Valley Forge cantonment. In France, when Benjamin Franklin was told of this situation, he responded: “You mean, Sir, Philadelphia has taken Sir William Howe.”[1] It was true that the British commander-in-chief had taken elaborate defensive measures behind a series of strong fortifications designed to prevent American attacks, but Franklin underestimated his foe. Howe and his men were relatively safe and less apt to risk aggressive maneuvers during the winter months; however, when it was deemed necessary to the garrison’s survival or when a golden military target presented itself, the British viper did make lightning strikes out of its fortifications.

The British learned through many of their wartime experiences that it was far better to use cavalry and other light forces to take full advantage of their mobility in order that they could move rapidly, achieve the lethal element of surprise, and attain and even surpass their assigned military goals. Quality is always more valuable than quantity when selecting troops for participation in special and secretive operations. The commanders for such military raids, such as Banastre Tarleton and John Grave Simcoe, needed to be “bold, courageous, and intelligent leaders, who persevered in the face of adversity.” These leaders, as opposed to other commanders of campaigns earlier in the war, came to fully comprehend the significance of “planning, preparation, and rapid execution as well as adherence to the principles of security, speed, simplicity” and shock-and-awe tactics for these type of missions.[2]

Throughout the roughly ten months of occupation, the territory between the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers was contentious ground and crisscrossed by armed troops of both armies. On February 12, 1778 Washington wrote to Gen. Nathanael Greene that, “The good People of the State of Pennsylvania living in the vicinity of Philadelphia and near the Delaware River” had “sufferd much by the Enemy carrying off their property without allowing them any Compensation, thereby distressing the Inhabitants, supplying their own Army and enabling them to protract the cruel and unjust war that they are now waging against these States.” The commander-in-chief also worried that the British “intend making another grand Forage into this Country[3] Washington also confessed to the Pennsylvania civilian authorities that this rural area was wide-open to “incursions of small parties of the Enemy … unless a sufficient number of Militia are immediately ordered out.”[4] To counter these raids and lead these American efforts, this difficult task was given to Pennsylvania militia Brig. Gen. John Lacey who pleaded to Pennsylvania President Thomas Wharton that “his force is at Last reduced to a Cypher, only 60 Remain fit for duty in Camp …” Lacey continued that his troops were “in no way Capable of Guarding so extensive a Country …”[5] Therefore, this region was completely susceptible to all British attacks and foraging missions without fear of major consequences from any American forces.

In Newtown, located approximately twenty-eight miles from Philadelphia proper, Col. Walter Stewart of the 13th Pennsylvania Regiment gathered a group of tailors and more than two-thousand yards of material to produce his men’s uniforms at Newtown’s oldest tavern, Old Frame House Tavern (today the Bird-in-Hand), which had been licensed as a tavern and ordinary around 1727.[6] Stewart would admit to President Wharton that his “poor fellows are in a most deplorable situation at present, scarcely a shirt to one of their backs & equally distress’d for the other necessarys, but they bear it patiently.”[7] The property was guarded by Pennsylvania militia and Continental troops under the overall command of Maj. Francis Murray, who was convalescing after recently being exchanged from his capture the previous year during the fighting at Long Island.

Two Loyalist units that were frequently utilized as auxiliaries to the regular British army were selected for a raid on this post in the Philadelphia countryside. These Loyalist commands, and others similarly formed during the occupation, had built such effective and occasionally ruthless military efficiency in accomplishing their assigned tasks, that fighting in Bucks and neighboring counties took on all the aspects of a vicious civil war. In this case, both commands were quite familiar with the Bucks County territory. The first troop of the provincial Philadelphia Light Dragoons, mustered into the British forces on January 8, 1778, was commanded by Capt. Richard Hovenden. He was commissioned by General Howe on November 7, 1777 and had travelled into Philadelphia from Newtown. The other unit was the Bucks County Volunteers governed by another Bucks County native, Capt. William Thomas, who originally was from Hilltop Township. Preceding the outbreak of war, he had moved to Penn Township located in Northampton County. In early 1778, he fled his home and made his way to Philadelphia to support the cause of the British Crown. By May 8, he was proclaimed a traitor by Pennsylvania with all of his property seized and sold by the state.[8]

According to Hessian Capt. Johann Ewald, on the evening of February 18, Brig. Gen. Sir William Erskine, the quartermaster general for British forces in Philadelphia, dispatched Captain Hovenden “with thirty horse and Captain Thomas, with forty foot” into Bucks County.[9] Capt. John Montresor, who was commissioned as the chief engineer in America, slightly disagreed with this expedition total, recording the raid as being much smaller with “24 Dragoons and Captain Thomas with 14 foot;” although his mistakenly recorded June 3 in his journal which was probably written later.[10] According to Loyalist scholar Todd Braisted, the dragoons were “almost certainly” uniformed in “green jackets, plush breeches with a helmet of some sort” while Thomas’s men “probably did not have a uniform unless they bought them” for themselves.[11] These relatively new Loyalist units had quickly gained invaluable military experience; on February 14 they ventured into Bucks County returning with most of the officials of the region with them as prisoners.[12]

On the night of the 18th, passing through the British fortifications that defended Philadelphia, the raiding party, their course undoubtedly governed by their own local knowledge and possibly by local Loyalist guides, covered the approximately twenty-six miles undetected to Jenk’s Fulling Mill, located in Bucks County’s Middletown Township on Core Creek just a short distance from the village of Newtown.[13] The American forces had been operating this facility for more than a year to prepare textiles for military use. According to Montresor the surprise attack was complete, with the entire guard of “Continental troops on their post” captured along with “a considerable quantity of cloth belonging to the poor people of the country of which they had been robbed by orders from the rebel head quarters.” Then, “with the secrecy the principal design required,” the force was divided and sent “a small distance off without firing a gun.”[14] After firing the mill, with stealth and complete silence the Loyalists next struck another nearby American post on the road to Newtown. According to Ewald, “Fortunately, they surprised the sentries and struck them down.”[15] The newspaper accounts slightly disagreed and stated that “they took prisoners the whole guard.”[16] It is possible since the Bucks County Volunteers were on foot that a number of them were placed with the growing number of prisoners while the dragoons quickly proceeded to their next objective of Newtown.

As the Loyalists soldiers entered Newtown and approached the residence of Major Murray, the element of surprise suddenly disappeared as a sentry fired upon them. Montresor recounted that, “This alarmed the guard about 40 yards distance who, being 16 in number, & under cover the guard house, immediately took to their arms and discharged their pieces on the troops surrounding them.” The Loyalists were alert and prepared for such a reaction. “After returning the fire & before the enemy could load a 2nd time,” [17] Ewald further described that “Captain Thomas stormed the house, killed a part of the pickets, and captured the major, five officers, three noncommissioned officers, and twenty-four privates.”[18] In addition, a number of workman and tailors employed by the Continental Army were seized as captives. There were no casualties on the Loyalist side during the entire action; however Montresor recorded in his journal that the Americans had altogether five killed and four wounded. The pro-British Philadelphia newspaper listed several of the prisoners:

Francis Murray, Major of their standing army

Henry Marfit, Lieutenant of militia,

John Cox, Ensign of their standing army,

Carnis Grace, Ensign of ditto

Andrew McMian, Ensign of Militia,

Charles Charlton, Quarter master of Standing army,

Eriel Welburn, Sergeant of ditto,

Patrick Coleman, ditto of ditto

James Moor, ditto of ditto

Twenty four privates of ditto, except one

Anthony Tate, a Grand Juror

The newspaper boasted that, “Too much commendation cannot be given to this gallant action.” The publication felt this raid, “must certainly meet with the applause of the public, and do great credit to the officers who conducted, and the men, under their direction, accomplished it.”[19] Capt. Friedrich von Muenchhausen, an aide-de-camp to General Howe, also lauded the incursion and estimated that the seized “cache of clothing material” was “enough for 500 men” to have received new uniforms.[20]

After Newtown, the raids continued in the Philadelphia countryside by both British regular troops and Loyalist units. A week later, Hovenden’s command captured and brought into Philadelphia nearly 150 oxen bound for Valley Forge, taking eight prisoners in the process. At the same time, the Reverend Henry Melchior Muhlenberg recorded in his journal on February 17 that “Today we heard that on last Saturday a company of horsemen (Tories) from Philadelphia made a sortie as far as Wentz’s tavern on the Shippach pike and Pawling’s mill and did some damage.”[21] In April, a party of Loyalist horse travelled north out of the city to Bristol on the Delaware River and seized Col. Joseph Penrose and several other officers of the 10th Pennsylvania Regiment. There were many other small incursions; however, one of the largest and the final major foray into the countryside was on May 1, 1778; only weeks before the British evacuation of Philadelphia. On this occasion, nearly 850 troops, including the Philadelphia Light Dragoons and the Bucks County Volunteers, virtually decimated Lacey’s command, encamped at the village of Crooked Billet, once again employing the elements of complete swiftness and surprise.

As a result of these frequent raids and the fact that regional Loyalists continued to transport supplies, forage and materials to the British garrison, the Continental Congress resolved on February 27 to advocate death for any Loyalist seized marauding within seventy miles of an American general officer. In a distributed broadside, they announced on the same date that “The deluded tools of the enemy, who are committing treason against America would do well to peruse the following Resolution of Congress with attention. They may rest assured, those of them who shall be hardy enough to violate the act, will meet with condign and exemplary punishment whenever they are taken.”[22]

In June of 1778, following the British evacuation of Philadelphia, the Philadelphia Light Dragoons were dissolved and men were attached to the British Legion and the Queen’s Rangers. The unit’s commander, Captain Hovenden, continued to serve as an officer in Tarleton’s British Legion and was captured at Yorktown; he retired in 1783 on half-pay. The Bucks County Volunteers were dissolved as well after Philadelphia was abandoned; Captain Thomas and many of his men attached themselves to the Queen’s Rangers where they continued to receive pay. Thomas later claimed he was seconded as a provincial captain from December 1782 until the end of the war in October 1783. He also retired half-pay as a captain.[23]

On the American side, the ranking officer, Maj. Francis Murray, on furlough at the time of his capture, was not as fortunate during his second time as a prisoner of war; he was not as quickly exchanged by the British. Washington noted that Murray was with a “number of respectable inhabitants” when seized “at Newtown with his family.”[24] He was confined as a prisoner-of-war on Long Island until traded nearly two years later on December 25, 1780. The following year, Murray retired from military service and went into politics on the county level, ultimately elected a Commissioner of Bucks County. In 1783 he returned to the military, appointed first as Lieutenant of Bucks County and in 1790 commissioned as a general in the Pennsylvania militia. He went on to become a merchant in Newtown, opening a retail store only a short distance from where the 1778 fighting took place. As compensation for his military service, he was awarded 750 acres in western Pennsylvania.[25]

All in all, the Newtown, and other similar raids, were militarily successful for the Loyalists. At Newtown, the Loyalists achieved complete surprise, accomplished their mission without a single loss, and covered fifty-six miles in only twenty-two hours; however, in the end, all of these extraordinary efforts into the countryside were for naught. On June 17, the last of the British troops (except for a few stragglers that were caught by American forces) departed Philadelphia leaving a devastated city to be re-occupied as the American capital. These tragic civil war-type actions that ran rampant throughout the American Revolution may be best summarized by a Hessian officer, Adjutant General Maj. Carl Leopold Baurmeister, who had the opportunity to view first-hand the devastation. “Everybody is disillusioned, and a disastrous indecision undermines all the American provinces. No matter how this war may end, as long as this mess continues, the people suffer at the hands of both friend and foe. The Americans rob them of their earnings and cattle, and we burn their empty houses; and the moments of sensitiveness, it is difficult to decide which party is more cruel. These cruelties have begotten enough misery to last an entire generation.”[26]

[1] Gordon S. Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (New York: Penguin Press, 2004), 190.

[2] Robert L. Tonsetic, Special Operations During the American Revolution (Havertown, PA: Casement Publishers, 2013), 247-248.

[3] George Washington to Nathanael Greene, February 12, 1778, Richard K. Showman, et al, eds., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, 1 January 1777-16 October 1778, 13 vols. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980), 2:281.

[4] Washington to Thomas Wharton, February 12, 1778, Samuel Hazard, Pennsylvania Archives, Series 2, 19 vols. (Philadelphia: Joseph Severns & Company, 1852), 6:254

[5] John Lacey to Wharton, February 15, 1778, Ibid, 265.

[6] Willis M. Rivinus, Early Taverns of Bucks County (New Hope, PA: 1965), 57-58.

[7] Walter Stewart to Wharton, February 21, 1778, Pennsylvania Archives, 285.

[8] Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission (PHMC), Historical Marker Nomination Form: Loyalist Raid of 1778 , submitted by David B. Long. Harrisburg, 2000; Terry A. McNealy, Bucks County: An Illustrated History (Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Historical Society, 2001), 129

[9] Joseph P. Tustin, Diary of the American Way: A Hessian Journal-Captain Johann Ewald (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 120.

[10] G.D. Scull, ed., The Montresor Journals (New York: New York Historical Society, 1881), 495.

[11] Todd Braisted, e-mail message to author, January 21, 2018.

[12] William Henry Siebert, The Loyalists of Pennsylvania (Boston: Gregg Press, 1972), 49.

[13]Individuals including John Granger, Richard Swanwick, John Roberts, John Knight, Christopher Sower Abraham Iredell and Gideon Vernon admitted to acting as guides for British Army and Loyalist raids into Bucks and Philadelphia Counties (present day Montgomery County was originally a part of Philadelphia County at this time); John W. Jackson, With the British Army in Philadelphia 1777-1778 (San Rafael, CA: Presidio Press, 1979, 320; “Fulling” was a process of shrinking and pressing cloth in order to increase its weight and bulk.

[14] Montresor, Journals, 495-496

[15] Ewald, Diary, 120.

[16] Pennsylvania Ledger or the Philadelphia Market-Day Advertiser, February 21, 1778.

[17] Montresor, Journals, 496.

[18] Ewald, Diary, 120.

[19] Pennsylvania Ledger, February 21, 1778.

[20] Ernst Kipping, and Samuel Stelle Smith, eds., At General Howe’s Side 1776-1778: The Diary of General William Howe’s aide de camp, Captain Friedrich von Muenchhausen (Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1974), 48.

[21] Theodore G. Tappert and John W. Doberstein, eds., The Journals of Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, 3 vols, (Camden, ME: Picton Press, 1993), 131.

[22]Journals of the Continental Congress, February 27, 1778, Worthington Chauncey Ford, Journals of the Continental Congress 1774-1788, 34 vols. (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1908) 10:204-205.

[23] Rene Chartrand, American Loyalist Troops 1775-1784 (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2008), 14; Walter T. Dornfest, Military Loyalists of the American Revolution: Officers and Regiments, 1775-1783 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2010), 164, 334.

[24] Washington to Wharton, February 23, 1778, Edward G. Lengel, ed., The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Series, December 1777-February 1778, 24 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), 13:651.

[25] Edward R. Barnsley, The Tory Raid on Newtown in 1778 (Doylestown, PA: Bucks County Historical Society, 1976), David Library of the American Revolution Vertical Files.

[26] Bernhard A. Uhlendorf, trans., Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals 1776-1784 of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces (New Brunswick: NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1957), 362

One thought on “The Loyalist Raid on Newtown: The Consequences of Being Surprised”

A beautifully written and well-researched piece! Just one question, though, regarding your reference to the later action at Crooked Billet. Were any Bucks County Volunteers at Crooked Creek with Simcoe? Or were they ALL busy carting Joseph Galloway’s furniture down the road in the other direction from Trevose to Philadelphia through the night of 30 April 1778? I’ve been trying to research who guided Simcoe and the QR to Crroked Billet, but had ruled out any of the Bucks men.