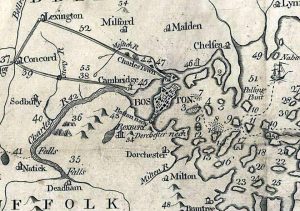

When Parliament passed the Boston Port Bill in 1774, in an attempt to break the Massachusetts colonists of their resistance to crown policy, it also authorized Gen. Thomas Gage to undertake any military measures necessary to help bring the colony under control. Gage quickly responded by requesting naval warships be sent to the New Hampshire coast, to Cape Ann and to Boston’s south and north shores. He also dispatched soldiers and loyalists to Middlesex, Essex and Worcester Counties with instructions to map the roads and topography, sample the political moods of the countryside and discover what they could about suspected provincial supply depots.[1]

In late winter and early spring of 1775, Gage received a series of dispatches from London ordering him to not only arrest the leaders of Massachusetts’s opposition party, but to launch a major strike against the apparently growing provincial stockpiles of weapons and munitions. As he contemplated these orders, Gage considered a variety of military options, including a long-range strike against the large store of weapons located in the shire town of Worcester, forty miles west of Boston. Realizing that this was much too risky a venture, the general decided instead to seize the military supplies reportedly stored at Concord, only half as far away as Worcester.

Gage’s plan called for approximately seven hundred men composed of the elite grenadiers and light infantry from several regiments and a company of marines, to march from Boston to Concord under cover of darkness on April 18, 1775. This “strike force,” under the command of Lt. Col. Francis Smith of the 10th Regiment of Foot, was ordered to proceed “with the utmost expedition and secrecy to Concord where you will seize and destroy all the artillery, ammunition, provisions, tents, small arms and all military stores whatever. But you will take care that the soldiers do not plunder the inhabitants, or hurt private property.”[2] Gage instructed Smith to dispose of provincial supplies by breaking the trunnions off of cannon barrels, burning tents, dumping gunpowder and shot into local ponds and eradicating stories of food “in the best way you can devise.” To counter the problem of colonial alarm riders spreading word of the expedition, the general informed Smith that “a small party on horseback is ordered out to stop all advice of your march getting to Concord before you.”

However, one group that was noticeably absent from Gage’s instructions or subsequent accounts of the Battles of Lexington and Concord were the Loyalist guides who either volunteered or were recruited to assist the military expedition. Little has been written about the role Loyalists played in Gage’s military operation. Many historians suggest that perhaps two to three Loyalists accompanied Smith’s regulars. Likewise, the role of armed and mounted Loyalists present with General Percy’s relief force has been almost completely overlooked.

According to the Rev. William Gordon, “several” Loyalists were present with the army. “On the first of the night, when it was very dark, the detachment, consisting of all the grenadiers and light infantry, the flower of the army to the amount of 800 or better, officers included, the companies having been fitted up, and several of the inimical torified natives, repaired to the boats, and got into them just as the moon rose, crossed the water, landed on Cambridge side, took through a private way to avoid discovery, and therefore had to go through some places up to their thighs in water.”[3]

A review of primary sources, including Loyalist claims for compensation after the American Revolution, suggest that at least six Loyalists were recruited to assist Lieutenant Colonel Smith’s expedition by navigating colonial roads and assisting troops in locating military stores in Concord. Among the guides were former Harvard classmates and friends Daniel Bliss of Concord and Daniel Leonard of Taunton. Both were well established attorneys who were forced to flee to the safety of Boston in 1774.[4] It was suspected by many Massachusetts Loyalists that Leonard was the anonymous author “Massachusettensis,” who had published prior to Lexington and Concord a series of pro-government letters drafted in response to the political arguments of John Adams.

Also present as guides were Dr. Thomas Boulton of Salem and Edward Winslow Jr. of Plymouth. Boulton was a vocal supporter of Crown policies towards Massachusetts and was forced to flee to Boston in 1774. Winslow held several political and legal posts in Plymouth County. Sensing a radical shift in the political mood in October of 1774, he abandoned his estate and also retreated to Boston.[5] Another Loyalist was Boston-born William Warden, a shopkeeper, grocer and barber. Unlike many of his station, Warden had been opposed to the political and violent activities of the Massachusetts “patriots” since the Stamp Act.

It appears that the guides were interspersed throughout the British column of march. Lt. William Sutherland of the 38th Regiment of Foot references on two separate occasions a “guide” at the front of the column. “When I heard Lieut. Adair of the Marines who was a little before me in front call out, here are two fellows galloping express to Alarm the Country, on which I immediately ran up to them, seized one of them and our guide the other, dismounted them and by Major Pitcairn’s direction gave them in charge to the men.” In a separate letter, Sutherland describes how a Loyalist guide identified a captured American prisoner as being a person of importance. “I mett coming out of a cross road another fellow galloping, however, hearing him some time before I placed myself so that I got hold of the bridle of his horse and dismounted him, our guide seemed to think that he was a very material fellow and said something as if he had been a Member of the Provincial Congress.”[6]

A newspaper account from May 3, 1775 suggests that some of the guides were armed. According to the Massachusetts Spy, “A young man, unarmed, who was taken prisoner by the enemy, and made to assist in carrying off their wounded, says, that he saw a barber who lives in Boston, thought to be one Warden, with the troops . . . he likewise saw the said barber fire twice upon our people.”[7]

In addition to leading the column to Concord, the guides had the responsibility of assisting search parties in locating military stores. “The troops renewed their march to Concord, where, when they arrived, they divided into parties, and went directly to several places where the province stores were deposited. Each party was supposed to have a Tory pilot.”[8] An American prisoner captured during the retreat from Concord later recounted that British troops identified the “Boston barber” Warden as “one of their pilots”.[9]

General Gage had also made contingency plans in case the expedition to Concord was in danger or jeopardy of failure. In the event of an emergency, Gen. Hugh, Earl Percy and his brigade of four regiments with artillery support were to march to the expedition’s aid. At six o’clock on the morning of April 19, a rider from Lieutenant Colonel Smith arrived in Boston requesting assistance. After some delay, over one thousand soldiers marched out of Boston towards Lexington.

At least seven Loyalists were present in Percy’s relief force. George Leonard of Plymouth served as a mounted scout.[10] A successful businessman in his own right, Leonard noted that “he went from Boston on the nineteenth of April with the Brigade commanded by Lord Percy upon their march to Lexington. That being on horseback and having no connexion with the army, he several times went forward of the Brigade, in one of which excursions he met with a countryman [fellow American] who was wounded supported by two others who were armed. This was about a mile on this side of Lexington Meeting House. The deponent asked the wounded person what was the matter with him. He answered that the Regulars had shot him. The Deponent then asked what provoked them to do it – he said that some of our people fired upon the Regulars, and they fell on us like bull dogs and killed eight and wounded nineteen. He further said that it was not the Company he belonged to that fired but some of our Country people that were on the other side of the road. The Deponent enquired of the other men if they were present. They answered, yes, and related the affair much as the wounded man had done. All three blamed the rashness of their own people for firing first and said they supposed now the Regulars would kill everybody they met with.”[11]

Two other men, Abijah Willard of Lancaster and John Emerson of Worcester, also volunteered to serve as mounted guides. Emerson, a house joiner and carpenter by trade, was given the dangerous task of delivering “despatches from the British headquarters in Boston to Earl Percy, then covering the retreat of the troops from Concord.”[12] Willard, a veteran of the Siege of Louisbourg and French and Indian War, was positioned in advance of the column to identify any “ambush laid for the troops.”[13]

Loyalists Thomas Beaman of Petersham, Thomas Aylwin of Boston, and Walter Barrell of Boston, all asserted that they joined Percy’s relief column either on their own volition or at the request of General Gage. According to Barrell, “when the Lexington affair of the Rebells firing on His Majesty’s troops occurred, he voluntarily associated with a number of friends to Government who offered their services to General Gage in any capacity to oppose the rebels.”[14] Aylwin recalled, “on the day of the skirmish at Lexington, General Gage asked him to enrol himself as a volunteer.”[15]

Not all Loyalist guides and volunteers made it back to the safety of Boston. John Bowen was a former officer of the 45th Regiment of Foot. In 1767 he retired from military service and settled in Princeton, Massachusetts. However, because he refused to recognize the authority of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, he was arrested and confined to a jail cell in August, 1774. Upon release, he fled to Boston. On April 19, Bowen recognized that “Gage had failed to procure [guides] for Lord Percy’s Brigade, he volunteered for the duty and conducted the force to Lexington.”[16] Later that day, the retired officer “was taken prisoner in returning from that skirmish.”[17]

One guide asserted, somewhat questionably, that he accompanied the British expedition out of mere curiosity. “The Petition of Samuel Murray, now a Prisoner of War, in the Town of Rutland, humbly sheweth: that on the nineteenth day of April AD 1775, Your Petitioner being then, an Inhabitant of the Town of Boston, & a Student of Physick there, was unfortunately induced, from mere Curiosity, unarmed & as a Spectator only, to follow the British Troops on their March to Lexington – but long before they reached that Place, recollecting the Troubles & dangers, to which he might be exposed, actually separated himself from them, & on his Return, being known to some People of Cambrige, was apprehended by them, on suspicion only & confined.”[18] Given his status as a prisoner of war, it was more likely Murray was merely attempting to craft a defense to the accusations leveled against him.

Some individuals were mistakenly identified by Massachusetts locals as guides. Harvard tutor Isaac Smith Jr. made the grave error of merely directing Percy’s relief column towards the correct turn at a fork in a road. For his efforts, Smith was vilified by many colonists.

The presence of Loyalists with the British column eventually garnered the attention of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. On June 16, 1775, the congress proposed to pardon all enemies who surrendered, except General Gage, Admiral Graves, “and all the natives of America, not belonging to the navy or army, who went out with the regular troops on the nineteenth of April last, and were countenancing, aiding, and assisting them in the robberies and murders then committed.”[19]

Following Lexington and Concord, many of the Loyalist guides were recruited into Timothy Ruggles’ Loyal American Association. By July 5, 1775, the association was composed of five companies of Loyalists. The companies were charged with the responsibilities of protecting various neighborhoods of Boston via “constant patroling party from sunset, to sunrise [to] prevent all disorders within the district by either Signals, Fires, Thieves, Robers, house breakers or Rioters”[20] The organization also would be called out in the event of fire: “In case of Fires your company officers & privates to repair immediately to ye place without arms to assist in extinguishing it & upon all duty to wear a white Scarf round the left arm to prevent Accidents.”[21]

Unfortunately, the official reports of April 19, 1775 from Lieutenant Colonel Smith, Major Pitcairn, Lord Percy and General Gage fail to mention the contributions of the Loyalist volunteers who served with the British regulars that day. It is likely the omission was intentional as the officers wished to protect the safety of their guides. As the war progressed, the guides continued to provide military and logistical support to the Crown. Following the war, many of them resettled in Canada or returned to England.

In May, 1775, Thomas Beaman was appointed a wagon master to the British Army.[22] Beaman died in Bedford, New York in November, 1780. After the war, his widow and children settled in Digby, Nova Scotia.[23] In 1777, Daniel Bliss was appointed an assistant commissary general with General Burgoyne’s Army. Following Burgoyne’s defeat, he was placed in charge of the whole commissariat from Niagara Lake to the most westerly British outposts.[24] In September, 1778, he was formally banned from Massachusetts by the Massachusetts legislature. On November 28, 1780, John Hancock signed the order declaring Bliss’s Massachusetts estate forfeited and seized. Following the war, Bliss was appointed a Judge of the Court of Common Pleas in New Brunswick, Canada. He died there in 1806.

George Leonard would finance the construction of seven armed vessels and three transports for service with the British Navy stationed at Newport, Rhode Island. This small fleet successfully destroyed eleven American vessels harbored at Martha’s Vineyard and forced the island to turn over necessary provisions for the British Army.[25] At the end of the war, he settled in New Brunswick and was active in politics for thirty-six years. He died on April 1, 1826.

The barber William Warden was recruited to engage in intelligence operations against the local rebels. On one occasion, “he was sent by General Gage to Salem and Marblehead to receive intelligence from Dr. Benjamin Church, but failed to execute his business.”[26] He also served as a courier, delivering messages to various British posts around Boston. In 1776, he and his family fled from Boston to Shelburne, Nova Scotia.[27]

After Lexington and Concord, Daniel Leonard continued his legal service to the Crown in Bermuda and England. At the conclusion of the war, he retired to London, England. On June 27, 1829, Leonard committed suicide by shooting himself.[28]

[1] E. Alfred Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts: Their Memorials, Petitions and Claims (London: Clearfield Company, 1930), 26-27. One loyalist recruited for scouting missions was Thomas Beaman. Beaman was a prominent Loyalist who owned property in Petersham, Murrayfield and Lancaster, Massachusetts. An outspoken critic of the growing violence and political chaos in Massachusetts, on January 2, 1775, he and thirteen other Loyalists signed a petition declaring that they would “not acknowledge or submit to the pretended authority of any Congress, Committee of Correspondence or other unConstitutional Assemblies of men but at the risk of our lives if need be oppose the forcible exercise of all such authority.” On multiple occasions, Beaman was recruited by Gen. Thomas Gage to travel the countryside to “discover the real designs of the leaders of the rebellion.” Ibid.

[2] General Gage to Lieutenant Colonel Smith, April, 18, 1775, Thomas Gage Papers, William L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan.

[3] An Account of the Commencement of Hostilities between Great Britain and America, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, by the Rev. Mr. William Gordon, of Roxbury, in a letter to a gentleman in England, May 17, 1775 (emphasis added). Northern Illinois University Libraries, Digital Collections and Collaborative Projects, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A83085.

[4] Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts, 35-36 and 191-194.

[5] Ibid., 43-44 and 300.

[6] Lieutenant William Sutherland to Sir Henry Clinton, April 26, 1775; Lieutenant William Sutherland to General Thomas Gage, April 27, 1775, Allen French, General Gage’s Informers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1932), 58-61.

[7] Massachusetts Spy, May 3, 1775. Northern Illinois University Libraries, Digital Collections and Collaborative Projects, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A83085.

[8] Ibid. The quote also asserts “[one] party went into the goal yard, and spiked up and other ways damaged two cannon belonging to the province, and broke and sat fire to the carriages – They then entered a store and rolled out about an 100 barrels of flour, which they unheaded, and emptied about 40 into the river; at the same time others were entering houses and shops, and unheading barrels, chests, etc., the property of private persons; some took possession of the town house, to which they set fire, but was extinguished by our people without much hurt. Another party of the troops went and took possession of the North bridge.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts, 194-195.

[11] Deposition of George Leonard, Boston, May 4, 1775. Allen French, General Gage’s Informers, 57-58.

[12] Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts, 128-129.

[13] Ibid., 297-298.

[14] Ibid., 24-25.

[15] Ibid., 18. Thomas Beaman identified himself as a “volunteer” and “guide to Lord Percy”. Ibid., 26-27.

[16] Ibid., 45-46.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Petition of Samuel Murray to the Massachusetts House of Representatives, March, 1777. Lorenzo Sabine, Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution (Boston, 1864), 520. According to Sabine, Murray graduated from Harvard College in 1772. In a general order issued on June 15, 1775, Murray was released from custody and ordered confined at his father’s homestead in Rutland. In 1778, he was banished from Massachusetts by legislative order. He died prior to 1785 in exile.

[19] Massachusetts Provincial Congress, June 16, 1775. Northern Illinois University Libraries, Digital Collections and Collaborative Projects, http://amarch.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A78567.

[20] Timothy Ruggles to Francis Green, November 17, 1775; Great Britain, Public Record Office, Audit Office, Class 13, Volume 45, folio 476.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts, 26-27.

[23] Ibid., 26-27.

[24] Ibid., 35-36.

[25] Ibid., 194-195.

[26] Ibid., 290.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid,, 191-194.

One thought on “The Loyalist Guides of Lexington and Concord”

Enjoyable and informative article, Alex. Loyalist involvement on the 19th of April has always been on the fringes of my historical consciousness but I’ve never done any looking into the topic. I must admit more of those folks had an involvement than I suspected. Thanks for filling one of the many gaps in my knowledge.

Having a connection with the Canadian Maritimes, I always enjoy reading about the people who settled there. To this day, many Maritimers talk of closer ties with Boston and New England than with the rest of Canada.