When people think about Thomas Jefferson, they think of a founding father, an advocate of liberty, and an American Patriot. But what people don’t normally think about is Thomas Jefferson’s scientific mind. Jefferson was a man who explored anything and everything that attracted his interest. He took it upon himself to value knowledge above almost everything else, including politics. But he did not merely acquire knowledge. Rather, whenever possible, he found practical uses for it. This fascination of his led to many incredible discoveries that certainly promoted the growth of the American scientific community. Many of his discoveries and ideas even hold influence over how we do things today.

While each scientific field during the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century was arguably much smaller than they are today, the fact that Jefferson explored nearly all of them is a remarkable aspect of his life. He was an avid agriculturist, botanist, geologist, meteorologist, and even paleontologist. The fact that he was able to discover so much with the limited resources of his time makes his accomplishments all the more impressive.

During Jefferson’s life, most of what is now considered science was instead labeled as philosophy.[1] In 1743, Benjamin Franklin established the American Philosophical Society, which still exists today. Thomas Jefferson joined the American Philosophical Society in 1780 during the heat of the Revolutionary War. In 1781, he was elected as a counsellor. Throughout the thirty-five years he was a member, he served on many committees and in other important positions. In 1797, Jefferson was elected president of the society, and he retained that position for the following eighteen years. He said his election to president of the society was the most “flattering incident of his life”[2] – even though just days before he had become Vice-President of the United States. Clearly the appeal of science had a greater impact on him than politics.

It was through the American Philosophical Society that Jefferson contributed much of his efforts to the scientific community. He was passionate about his work for the organization, and once said he wanted “to contribute any thing worthy the acceptance of the society.”[3] Indeed, that is precisely what he did. Many of the fossils he discovered he donated to the Society for further study. Other discoveries by Jefferson were contributed as well, and undoubtedly the society made good use of his theories for handling archeological sites. He served on what was known as the “Bone Committee,” which held the rather ambitious goal of procuring and assembling an entire skeleton of a mammoth. When he paid for a major dig led by William Clark at Big Bone Lick, Kentucky, more than three hundred bones were shipped back, many of which he donated to the society.[4]

Jefferson went on a tour of several lakes in New England to study plant life. However, it is unfortunate that none of his botanical work was ever presented to the society.[5] He also financed a great deal of exploration of the West to the Pacific Ocean, utilizing the American Philosophical Society as a valuable resource. These expeditions brought back much information about the Native Americans who lived there, along with geographical and botanical data.[6]

Although they rejected his resignation as president three separate times, the society finally accepted it in 1815. When Jefferson died eleven years later, they voted to have the President’s chair draped in black for six months.[7] His passion and contributions to this organization make a compelling statement regarding his desire to improve science as a whole. There is no question that he personally improved the capabilities of the society during the time he was there, even before he became its president. The American Philosophical Society is the oldest scholarly organization in the United States, and it has made significant contributions to science over the years. Were it not for Jefferson’s efforts, the society’s accomplishments would likely not be so numerous or profound.

Thomas Jefferson wrote extraordinarily detailed information in his Notes on the State of Virginia, which depicted just about everything, including the state’s cities, ports, climate, military capabilities, natives, government, religion, customs, currency, history, and geography. When he wrote in his notes about the various rivers that flow within Virginia, he listed important information such as which ones were navigable and, if applicable, which parts of rivers were navigable. If certain rivers were not navigable, he described sections of them which were accessible by canoe or other small watercraft. Also included were many of the tributaries to these rivers. Specifically, he provided detailed information regarding the Roanoke, James, Nansemond, Pagan, Chickahominy, and Appomattox Rivers. Waterfalls and other hazards were mentioned as necessary.[8]

His notes contained extensive information about Natural Bridge. The way he described it, one had to crawl on hands and knees in order to peer over the side and look down from its great height. He said that doing so for more than a minute gave him a “violent headache.”[9] He also, on a more positive note, said of the view that the “rapture of the spectator is really indescribable!”[10]

His notes detailed the Blue Ridge and Appalachian Mountains in the western portion of his state. He described their location, height, patterns, and where the mountain ranges led outside the state of Virginia.[11] These notes were highly valuable for cartographers and geographers who held interest in Virginia’s beautiful and diverse landscape. The observations from Jefferson helped the scientific community in America further their understanding of Virginia’s weather patterns, plant life, and other aspects related to natural science.

Jefferson’s desire to understand the rich qualities of North America did not stop within the boundaries of Virginia. During his presidency, he purchased the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon Bonaparte for fifteen million dollars. Afterward, he wanted to know exactly what it was he had procured for the country, so he commissioned a small expedition of army servicemen led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to venture out west in search of a water passage leading to the Pacific Ocean.[12] This venture was successful. While every watershed ended at the Rocky Mountains, Lewis and Clark were ultimately able to find another water route once they crossed the Rockies that did in fact lead to the Pacific.[13] They brought back a great deal of intelligence about Native American tribes along with information about wildlife and plants. Once they returned, Jefferson made good use of this information for the benefit of the United States.[14]

In the front room of Monticello, there is a map of the United States that Jefferson owned which displays in great detail the political boundaries and geological features of the country prior to the Louisiana Purchase.[15] After completing the Louisiana Purchase, he funded enormous efforts to map the North American continent. Lewis and Clark contributed a great portion of these efforts, but there were other cartography projects that occurred as well. By the end of Jefferson’s life, Americans possessed a great deal more knowledge about what lay to the west. There can be no doubt the new maps that came into existence as a result of Jefferson’s work encouraged Americans to settle in the West with a renewed vigor. After Jefferson’s death, the famous Oregon Trail led settlers across the entire North American continent, an event likely influenced by Jefferson’s cartographic efforts.

At Monticello, Jefferson placed various artifacts and objects from his studies on display in the front room of the house. In fact, he intentionally designed the front room so it did not have a staircase and served as a pseudo-museum full of items from his collection. The stairs instead were built in the middle-rear of the home, and they were narrow and steep. This design, while often grueling and uncomfortable (especially for the pregnant women of his household), conserved a great deal of space.[16]

Among the items put on display for his guests were an abundant number of Native American artifacts hung along the walls and second-floor railing. These were colorful and beautiful souvenirs of the expeditions Jefferson sent out west.[17] There was another item he had on display that was particularly remarkable: a jawbone from the long-extinct mastodon. It wouldn’t be difficult to imagine how this fossil in particular absolutely bewildered his guests.[18]

Jefferson developed new methods for handling archaeological sites. Previously, archeologists would simply dig away at the earth until they found something, which often destroyed artifacts. Upon discovering an Indian burial mound on his property, Jefferson devised a way to excavate it that was well ahead of methods existing at the time. Instead of digging straight down into the ground, he systematically cut wedges into the mound. Doing so allowed him to examine the various rock and soil layers as he progressed downward. This, of course, enabled him to roughly determine the age of the various artifacts discovered and to do so without risking their destruction. This method is still used today in some archeological sites, although his precise method is considered primitive by modern standards.[19]

In order to understand how Thomas Jefferson’s scientific mind affected his extraordinary influence on the scientific community, it is crucial to discuss several of his inventions. Most of these were designed and constructed at his plantation home near Charlottesville, Virginia, the magnificent Monticello. As a man of science, Jefferson always carried on his person a variety of tools which he used to quickly capture ideas and information. Among these objects were a pocket notebook, pencil, small telescope, compass, drafting instruments, thermometer, architect’s scale, pocket knife, and even an odometer so he could measure the distances of his travels. Another object he usually kept nearby was a portable lap desk.[20] These items can be viewed at the Jefferson Foundation Museum just down the mountain from Monticello. Many of these tools were undoubtedly used to help compile his Notes on the State of Virginia along with other documentation and samples that were sent to the American Philosophical Society.

One of the items he invented was a special plow made specifically as an upgrade to the existing plow design. He believed agriculture was the most important science, understandable since agriculture was the backbone of human civilization at the time.[21] Jefferson’s plow was specifically engineered to run through the dirt as effectively as mathematically possible. Using principles that originated from Sir Isaac Newton’s work, his final design was impressive, effectively doing precisely what he wanted it to.[22] Explaining his plow, he said, “It is on the principle of two wedges combined at right angles, the first in the direct line of the furrow to raise the turf gradually, the other across the furrow to turn it over gradually. For both these purposes the wedge is the instrument of the least resistance.”[23]

Unfortunately, the plow never became popular as he had hoped. It is uncertain why that was, because improving something as significant and important as the plow would obviously render a vast amount of farm work much, much easier. Still, surprisingly, the American Philosophical Society never did seem to catch on to the idea, so they never spread Jefferson’s design across America.[24] His plow did receive a certain amount of recognition, however. The Italian Agricultural Society in Florence, Italy, awarded him a prestigious certificate. Also, the plow appeared in the Domestic Encyclopedia thanks to James Mease, which adds even more curiosity as to why the design never caught on. The French Society of Agriculture gave Jefferson a medal and membership in their organization as a foreign associate. Jefferson never wanted a patent for it, however, and his main desire was for the knowledge to be spread and used by others for their benefit. To him, knowledge was something to be shared with all mankind.[25]

Thomas Jefferson was also an avid meteorologist. For more than fifty years he took rigorous notes on weather patterns around Virginia in order to better understand climate in the eastern United States. His methods for doing so are similar to those utilized today by the National Weather Service. That is to say, he consistently measured the highest and lowest temperature each day and any precipitation that occurred. He woke at dawn every day, which was when he considered the atmosphere to be the coldest throughout any twenty-four hour period, and immediately recorded the temperature. He also took care to measure again at four o’clock in the afternoon every day, which was when he thought the temperature was the hottest.[26]

He constructed a weathervane on top of the roof of Monticello. It was linked to a compass underneath which could be seen with convenience. It was through this that he collected much of his wind data at Monticello.[27] Although Jefferson also attempted to record information about winds and humidity, it proved to be a nearly worthless effort due to the unreliable tools that existed during his time. However, he is often considered to be the “Father of Meteorology” since he devoted so much effort to studying Virginia’s climate.[28]

At Monticello, Jefferson designed and built a fully functional sundial that he placed on one of the wooden walkways leading away from the house. This provides great insight into his mathematical as well as scientific genius, as designing and building a sundial requires very specific calculations and a thorough understanding of geometry. His device, a sphere constructed of locust wood, measured 10.5 inches in diameter. He drew large lines on the sundial to mark hours of the day, labeled with Roman numerals, and lines of a smaller length in between to mark the minutes in five-minute intervals. A bar called a meridian made of metal could rotate around the sphere with each end attached to the poles. To operate the device, one would simply move the meridian to where the dark-side shadow began. Here, it was possible to determine the time of day to an astonishing accuracy of two minutes.[29]

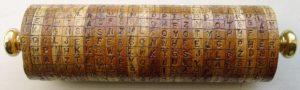

After the Revolutionary War, Jefferson served as the United States’ minister to France. He often had to exchange letters with other important individuals involved in the war. Most of the letters were hand-delivered, and French postmasters always opened and read them. Since Jefferson saw this as an obvious security risk, he invented a device that would encode the contents of each letter so only the recipient would understand its meaning.[30] The device was called a “wheel cipher.” It had random letters on it and was comprised of twenty-six disks arranged in a specific order. The wheel could be used to transform a message into a secret code that was meaningless to the nosy postmasters. Upon delivery of the letter, the recipient would use an identical wheel cipher to decode the message. Although the wheel was tedious to use, it was highly effective for sending secret messages.[31]

Jefferson was an avid botanist. At Monticello, he spent an abundant amount of his time gardening. Much of this was to find out what could be grown in eastern North America, as he suspected Virginia possessed a climate similar to that of Mediterranean Europe. He grew plants from all around the world and recorded his observations about them in a garden book. One of the plants he tried to grow in Virginia was grapes from Europe. Unfortunately, he never mastered this, and his attempts at growing a successful vineyard to produce wine failed year after year. Not until after his death was the right species for this discovered, and it became possible to own a vineyard in Virginia.[32]

He enjoyed the notion of developing a new American style of gardening that differed from that of Europeans. The idea was to create plots amidst the forest instead of out in the open. This was inspired by his philosophy that the entire forest and wilderness was really a giant nature-formed garden that should be admired and respected. In fact, he is quoted as saying, “The unnecessary felling of a tree, perhaps the growth of centuries, seems to me a crime little short of murder.” [33]

Thomas Jefferson also played a significant role in the development of patent law in the United States. In 1789, Congress created a three-man review board for patents. The leader of that board was Jefferson himself. While only a handful of patents were granted each year, the board saw many, many more applications. The result of the board was a renewed enthusiasm for inventions and improvements.[34] Jefferson, with his passion for science and technology, was thoroughly excited about this: “An act of Congress authorising the issuing patents for new discoveries has given a spring to invention beyond my conception. Being an instrument in granting the patents, I am acquainted with their discoveries. Many of them indeed are trifling, but there are some of great consequence which have been proved by practice, and others which if they stand the same proof will produce great effect.”[35]

Jefferson held a firm belief that as few patents as possible should be issued. Each consideration was based upon how original the invention was and also how it would affect society. This, of course, had much to do with his belief that knowledge belonged to everyone. He didn’t like the idea of anyone holding a monopoly on anything, much less an idea or invention that could benefit society as a whole.[36] Ultimately, the law was changed and an independent patent office was created. Its powers were a smooth blend between Jefferson’s beliefs that almost no patents should be granted and a rather automatic process of granting them to anyone who wanted one. The final iteration of this law came about in 1836, and it still exists today.[37]

Thomas Jefferson corresponded with several scientists in France, including Count George-Louis Leclerc Buffon. One of the big issues of the time was Buffon’s “scientific” account of the New World in his encyclopedia called Histoire Naturelle, where he claimed every animal and person who lived there was “degenerate.” He proposed this idea based on the notion of America’s humidity and climate, saying it made animals and people weaker and more fragile. American animals were always smaller than their European counterparts, and therefore less useful.[38] Jefferson, of course, took great offense to this and went on a mission with James Madison to debunk Buffon’s theory, as it unjustly tarnished America’s reputation. He informed Buffon that his researchers were subjective and flawed in their observations, that they had already decided their opinion on the matter before ever arriving in the New World to conduct research.[39]

James Madison used the weasel for proof. It was a species that existed in both Europe and in America, so it made an exemplary candidate for comparisons. Of course, average measurements between specimens from Europe and America were virtually identical, providing evidence that Buffon’s theory was wrong.[40] In his Notes on Virginia, Jefferson brought attention to the moose, one of the largest animals he could think of. This, of course, was pleasantly overkill for the argument. After sailing to Paris in 1784, he met with Buffon and described the moose to him. Buffon thought it was simply a misclassified reindeer, but Jefferson replied that a reindeer could walk underneath a moose’s belly.[41] Buffon told him that if he could produce an antler from a moose, he would relent from his theory of degeneracy. When Jefferson did so, Buffon was supposedly convinced. However, he died before he could make any retraction of it in his next edition of Histoire Naturelle.[42]

Thomas Jefferson also wrote to the famed British chemist Joseph Priestley. Priestley made incredible discoveries regarding electricity and light, and he developed carbonated water. Priestley combined science with theology, and angered many who felt threatened by his views. One of the most volatile opinions he possessed was the noble idea that the Bible was compatible with science. These ideas, naturally, fascinated Thomas Jefferson so much that he befriended Priestley.[43] When Priestley’s home in Britain was destroyed by a mob, he moved across the Atlantic to live in Philadelphia. Here he was welcomed and respected, particularly by Jefferson, who regarded Priestley as a mind who would strengthen America’s abilities in natural science.[44]

After Priestley’s arrival, he fell ill. Jefferson wrote him an invitation to stay at Monticello, saying the excursion away from Philadelphia might help him recover. He also wrote, “I learnt some time ago that you were in Philadelphia, but that it was only for a fortnight; & supposed you were gone. It was not till yesterday I received information that you were still there, had been very ill, but were on the recovery. I sincerely rejoice that you are so. Yours is one of the few lives precious to mankind.” [45]

There is a very tangible possibility that had he not been needed in the tumultuous American politics of his time, Thomas Jefferson would have been purely a scientist and philosopher. And odds are he would still be a famous individual today just as any other significant American scientist in our history books. He inspired Americans to seek out and pursue knowledge as the most precious commodity on the planet. He once said, “when men of sober age travel, they gather knowledge which they may apply usefully for their country.”[46]

[1] “Jefferson Lab: What did Thomas Jefferson do as a scientist?” accessed May 4, 2014, http://education.jlab.org/qa/historyus_01.html.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “The Jefferson Monticello: American Philosophical Society,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/american-philosophical-society ; Jefferson to Matlack, April 18, 1781, in Julian P. Boyd, editor, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 5 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1952), 490.

[4] “The Jefferson Monticello: American Philosophical Society.”

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (Richmond: J.W. Randolph, 1853).

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] “The Jefferson Monticello: The Lewis and Clark Expedition,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/lewis-and-clark-expedition.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Thomas Jefferson’s map of the United States on display at Monticello. Information was acquired via a guided tour of the house.

[16] Layout of Monticello on display at Monticello. Information was acquired via a guided tour of the house.

[17] Thomas Jefferson’s collection of Native American artifacts on display at Monticello. Information was acquired via a guided tour of the house.

[18] Thomas Jefferson’s collection of fossils on display at Monticello. Information was acquired via a guided tour of the house.

[19] “An outline History of Archaeology,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.age-of-the-sage.org/archaeology/history_of_archaeology.html.

[20] Jefferson’s many tools on display at the Jefferson Foundation Museum.

[21] “Jefferson Lab: What did Thomas Jefferson do as a scientist?”

[22] Ibid.

[23] Thomas Jefferson, 1794. Quote on display at the Jefferson Foundation Museum.

[24] “Jefferson Lab: What did Thomas Jefferson do as a scientist?”; “Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the Peacock Plow,” The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 1814, accessed May 22, 2015, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-08-02-0048.

[25] “The Jefferson Monticello: Dig Deeper – Agricultural Innovations,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/jefferson/dig-deeper-agricultural-innovations.

[26] “Thomas Jefferson’s Weather Records,” Library of Congress, 1776-1818, accessed May 22, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj7.059_0055_0102/.

[27] “Monticello’s Clever Windvane,” accessed May 14, 2015, http://boingboing.net/2009/06/25/monticellos-clever-w.html.

[28] “The Jefferson Monticello: Weather Observations.”

[29] “The Jefferson Monticello: Spherical Sundial,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/spherical-sundial.

[30] “The Jefferson Monticello: Wheel Cipher,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/wheel-cipher.

[31] “Jefferson’s Description of a Wheel Cipher,” Founders Online National Archives, Prior to 22 March, 1802, accessed May 22, 2015, http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-37-02-0082.

[32] “A Man of Wine, 200 Years ahead of his Time,” accessed May 14, 2015, http://www.dailyclimate.org/tdc-newsroom/2014/12/jefferson-wine-virginia.

[33] “The Jefferson Monticello: The Trees of Monticello,” Unknown Date, accessed May 22, 2015, http://www.monticello.org/site/house-and-gardens/trees-monticello; “Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book,” Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive, 1766-1824, accessed May 22, 2015, http://www.masshist.org/thomasjeffersonpapers/doc?id=garden_1.

[34] “The Jefferson Monticello: Patents,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/patents.

[35] “Jefferson to Benjamin Vaughan,” June 27, 1790, Library of Congress, accessed May 22, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/resource/mtj1.012_0663_0665/.

[36] “The Jefferson Monticello: Patents.”

[37] “The Jefferson Monticello: Patents.”

[38] “Slate: Thomas Jefferson Defends America With a Moose,” accessed May 4, 2014, http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2012/09/thomas_jefferson_s_moose_how_the_founding_fathers_debunked_count_buffon_s_offensive_theory_of_new_world_degeneracy_.html.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] “National Museum of American History: The Statesman and the Chemist: Thomas Jefferson and Joseph Priestley,” accessed May 4, 2015, http://blog.americanhistory.si.edu/osaycanyousee/2014/02/the-statesman-and-the-chemist-thomas-jefferson-and-joseph-priestley.html.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Jefferson to Joseph Priestley, March 21, 1801, in Barbara B. Oberg, ed., Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 33 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), 393-394.

[46] Thomas Jefferson, 1787. Quote on display at the Jefferson Foundation Museum.

3 Comments

An alternate history suggests itself from this account: Had the British simply granted their American Colonies representation in Parliament following the French and Indian War, the rebellion would likely have fizzled, without the necessity for revolution, never mind charges of treason &c. that would have driven prospective members of the Continental Congress beyond the pale of civilized British Imperial society.

Jefferson, Franklin, Warren and others might then have been engaged in even more pursuit of natural philosophy than they each managed anyway, and a golden age of British global influence over its European rivals could well have resulted.

Of course, history would have missed out on the bold and innovative commentaries on the relationship between citizens and their governments, as well as the outburst of developments in commerce and exploration that resulted from the Revolution and its subsequent events…. but it does make for a fascinating thought experiment,

Thank you for this detailed and informative discussion of a side of Jefferson’s personality that makes him all the more appealing as an historical figure!

And what of Jefferson’s pioneering anthropological thought as revealed in “Notes on the State of Virginia”? Specifically, his beliefs on race?

Of course, that is one of TJ’s less appealing traits…..

Anyone interested in a good read covering the “degenerate” episode would do well to read “Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Natural History in Early America” by Lee Alan Dugatkin. It is a great read and fairly short, but the book covers the subject very well.