The Royal Governor’s April 21, 1775 removal from Williamsburg’s Powder Magazine of gunpowder essential to Virginia’s defense caused an immediate furor among Virginians as news spread throughout the colony. The governor’s action was in response to George III’s direction to colonial governors to take control of arms and powder throughout the colonies, direction which had precipitated the clash at Lexington and Concord two days previously. The most famous reaction to the governor’s action was the march on the capitol by the Independent Company of Hanover County under the leadership of Patrick Henry, in what was the first armed revolt of the American Revolution in the South. During a tense morning in May just west of Williamsburg, Henry obtained payment for the gunpowder from crown officials in lieu of its return, averting a confrontation with the king’s military forces. At the same time, volunteers from the Independent Company of Albemarle County embarked on a similar march towards Williamsburg with the same goal, though with less dramatic results. Their action has been described in several accounts over the years, with varying degrees of consistency and detail.[1] This account seeks to put that action in historical context and describe it as thoroughly as the record allows, thus demonstrating that Albemarle County patriots were within days of preempting Patrick Henry in this historic affair.

Virginia’s Independent Companies

The Continental Association was established by the First Continental Congress in October 1774, under which each county was required to establish a committee to enforce its actions locally. By the end of 1774, many of Virginia’s counties, including Albemarle, had complied by establishing a committee of observation.[2] As the American Colonies’ relations with Great Britain deteriorated, at least twenty-seven of those counties also created independent companies of volunteers, which provided enforcement capability to the committees of observation, to whom they were responsible. Albemarle County’s Independent Company was organized in the spring of 1775 with “Terms of Inlisting” that required its volunteers “to be at all times ready to execute the command of the committee in defence of the rights of America.”[3] At that time the company consisted of a total of 155 rank and file.[4] By the summer of 1775 the company’s size had swelled to nearly 300.[5]

Dunmore Starts the Action

By the spring of 1775, His Excellency John Murray, Earl of Dunmore—Virginia’s royal governor—was unsettled by the actions being taken in Virginia that, in his view, were in preparation for conflict with Great Britain. The colonies had held their first Continental Congress in 1774 and in March 1775 the Virginia Convention had met to discuss how to deal with deteriorating relations with Great Britain. Since the governor had earlier been instructed by the king to control the colonists’ access to gunpowder, arms and ammunition, Dunmore decided to remove the supply of gunpowder stored in Williamsburg for colonial defense. He accomplished this by giving the keys to the town’s Powder Magazine to the Royal Navy’s Lieutenant Henry Collins, commander of the armed schooner HMS Magdalen, which lay in the James River below Williamsburg. During the early morning hours of Friday, April 21, Lt. Collins and a detachment of marines removed fifteen barrels of powder from the Magazine, transported them to the Magdalen, and thence to the frigate HMS Fowey, located near Norfolk. Colonists detected Lt. Collins’ party removing the powder and raised the alarm immediately.

Colonial authorities confronted the governor later that day and demanded the return of the powder. Dunmore indicated he had removed it to Royal Navy ships for security and would return it if needed for Virginia’s protection. For the moment this assurance, however mendacious, calmed matters in Williamsburg, but not throughout the rest of the colony where the response was heated. The news arrived in Fredericksburg on April 24, the very day the local independent company had mustered for drill. The company immediately notified its counterparts in adjacent counties, prepared to march to Williamsburg, and sent an emissary to gauge the reaction there. Peyton Randolph, Speaker of the House of Burgesses, counseled the companies against a march on the town based on the governor’s assurances concerning the return of the powder. Satisfied by this reassurance, on April 29, officers of the independent companies gathered in Fredericksburg and the local committee of observation voted not to march.[6]

Reaction in Albemarle County

News of the powder confiscation probably reached Charlottesville by April 24, but many members of the Independent Company of Albemarle County lived throughout the county and did not learn of it immediately. The news was sent to its members, but it was April 29 before the company could assemble to consider what action to take. The leaders of the company sent an express message to George Washington stating that the county in general and the independent company in particular were “truly alarmed and highly incensed” about the removal of the powder, and that they were willing to march to Williamsburg “properly equipped and enforce an immediate delivery of the powder or die in the attempt.”[7] They sought Washington’s counsel as to how to proceed, even though they had learned that the Independent Company of Spotsylvania County had already voted not to march.[8] By May 2, nothing had been heard from Washington; since the Albemarle County Committee of Observation was unavailable for guidance, the Independent Company voted to proceed to Williamsburg and “demand satisfaction of Dunmore for the powder.”[9] That decision was probably made after an eloquent address by Doctor (and Lieutenant) George Gilmer and was supported by the volunteers’ confidence in the leadership capabilities of Captain Charles Lewis.[10] Gilmer’s speech fell on receptive ears since the volunteers came to the May 2 meeting physically prepared to march.[11] They departed for Williamsburg that day.

Reaction in Hanover County

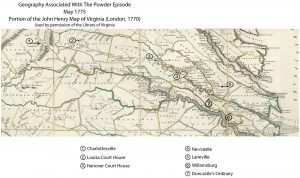

In Hanover County, Patrick Henry initiated action which would result in his meeting the Albemarle County Company on their march toward Williamsburg on May 5. Late in April, Henry had sent word to the Independent Company of Hanover County to meet on May 2 at Newcastle in eastern Hanover to consider what action to take. The deliberations of the Hanover County Committee and Independent Company lasted until late in the evening and included an emotional speech by Henry in which he decried the “recent plunder of the magazine in Williamsburg,” which he said was “part of the general system of [British] subjugation.”[12] The speech so inflamed the men’s enthusiasm that the decision was made to march to Williamsburg to demand a return of the powder or compensation therefor, and Henry was made captain of the volunteer company. He immediately dispatched a troop under Ensign Parke Goodall on a thirty-six-mile ride to Laneville, the home of His Majesty’s Receiver General Richard Corbin in southeast King and Queen County, to procure payment for the confiscated powder. Goodall’s men started from Hanover the evening of May 2, and arrived at Laneville later that night. They picketed Corbin’s house, but upon learning the next morning that Corbin was in Williamsburg, the troop continued their march to the capitol.[13]

The main body of the Hanover Independent Company left Newcastle on May 3 following a direct route to Williamsburg. They halted at Doncastle’s Ordinary, about fifteen miles west of Williamsburg, where Goodall’s contingent joined them that evening. By then, Henry’s forces numbered a reported “150 men and upwards.”[14] Corbin was eventually located in Williamsburg and provided a bill of exchange for £330—the presumed value of the powder—which was delivered to Henry on the morning of May 4.[15] Henry deemed that amount acceptable, and that same afternoon he and his men left Doncastle’s Ordinary to return to Hanover County.[16] Members of the company living near or west of Hanover Court House, forty-six miles from Doncastle’s Ordinary, arrived home no earlier than the afternoon of May 5, shortly before encountering the Albemarle Company on their march to Williamsburg.[17]

March of the Albemarle Volunteers

Information about the Albemarle Company march is limited to accounts written many years later, which provide only an outline of events. Philip Mazzei (1730-1816) commented on the march in his memoirs written thirty-five years later. Though he interwove events from the march with those related to an attack on Hampton, Virginia later in 1775, the two can be untangled with some degree of confidence.[18] Mazzei stated that the company left Charlottesville on foot rather than mounted. That is apparent based on the four days required for the march to Hanover Court House, compared with the three days required to reach Williamsburg by Lt. Gilmer and a mounted party which left July 11 in an action described below.

| Members of the Independent Company of Albemarle County Known to have Begun the March toward Williamsburg on May 2, 1775[19] | ||

| Charles Lewis, Captain | Thomas Martin, Corporal | Charles Liln. Lewis, Private |

| George Gilmer, Lieutenant | David Allen, Corporal | James Quarles, Private |

| John Marks, Lieutenant | John Lowry, Drummer | Reuben Lindsay, Private |

| William Wood, Sergeant | Edward Garland, Private | William Johnson, Private |

| William Terril Lewis, Sergeant | John Henderson, Private | Benjamin Harris, Private |

| John Martin, Sergeant | Isaac Wood, Private | |

| Fred. Wm. Wills, Corporal | Falvy Frazer, Private | |

Mazzei estimated the group was comprised of roughly 100 men, a surprising two-thirds of the 155 company members, with the number doubling by the next day as others joined the march. Presumably all were armed, though not all had gunpowder. Mazzei also stated that a portion of the Independent Company of Orange County joined the march on the second day, as his company was “crossing the boundary into Orange County.”[20] While it seems doubtful that their route extended as far north as Orange County, it is certain that the Company followed the Old Louisa Road which swings northeast towards Orange County, rather than the more direct Three Notched Road. The Orange County volunteers probably joined the march southeast of present day Gordonsville. Capt. Lewis’ apparent strategy was to march through the county seats of Louisa, Hanover, and New Kent Counties in order to increase the size of his command before reaching Williamsburg.[21]

A limited but important mention of the march’s terminus was made by Sgt. John Martin, who recalled that the company marched through Louisa County to Hanover County. His Albemarle County neighbor, Samuel Murrell, was more specific in stating that the company marched to Hanover Court House, at which point the march was countermanded. Benjamin Harris stated that he marched to Scotchtown, home of Patrick Henry.[22] It is likely that as the volunteers marched eastward through Louisa County, they encountered westbound travelers who passed on information that the Hanover Company had marched earlier, causing them to dispatch men to Scotchtown to determine whether the latter had already returned, while the main body continued on towards Hanover Court House.[23]

The company probably covered the seventy-four miles from Charlottesville to Hanover Court House in four days. Mazzei wrote of spending “four nights in the open.”[24] Presumably these were the nights of May 2–5. John Martin recalled he had spent “eleven days or upwards” that included two days getting to Charlottesville from his home.[25] That would allow at least nine days for the round trip from Charlottesville to Hanover Court House, with only the eastern leg being a forced march, consuming four days. This limited evidence shows that the volunteers made a rapid march to Hanover Court House, averaging eighteen miles a day, consistent with the objective of getting to Williamsburg quickly. The Independent Company of Albemarle County thus arrived at Hanover Court House at approximately the same time that Patrick Henry and the central-western Hanover members of his company arrived there from Doncastle’s Ordinary.[26]

This coincidental timing was fortuitous since it forestalled a redundant march to Williamsburg by the men from Albemarle County. No doubt Henry briefed them on his encounter with colonial authorities and reimbursement for the powder, which by that time reposed on HMS Fowey. According to Mazzei, “before his own companies drawn up in formation, with ours opposite, [Henry] made an eloquent speech of thanks.”[27] Mazzei thought that Henry had “no superior in eloquence or in patriotism.” Capt. Lewis asked his company for a vote on whether “to return as they came, or disband” and the men opted to disband.[28] This decision allowed the Albemarle County volunteers to make their individual ways home, at a more leisurely pace than that which brought them to Hanover County. Nevertheless, it would have been a footsore company that returned home around May 10. Though it had not culminated in conflict, the nearly 160 miles of marching on this “campaign” was a quick introduction to soldiering for the company’s members.

Afterward

Patrick Henry’s success in obtaining crown payment to the colony for the gunpowder was described in the May 5 edition of the Virginia Gazette. Copies of the latter reached Albemarle County by May 8, when the local Committee expressed their thanks to the Hanover volunteers for their actions. Members of the Independent Company of Albemarle County might have reflected that they had acted from similar motivation and at the same time (actually several hours earlier), and in a similar way, and deserved the same recognition that was accorded the Hanover County volunteers.[29] Distance from Williamsburg alone prevented the Albemarle contingent from taking the lead in obtaining restitution for the stolen gunpowder.

George Gilmer led a contingent of twenty-seven members of the Company on another trip to Williamsburg in July 1775, though with no clearer objective than to be available to oppose actions by Dunmore. They were joined by members of independent companies from fourteen other counties. This small “army” accomplished little and was asked to disband late in July by the Virginia Committee of Safety. Soon thereafter the independent companies were replaced by a military district system under which battalions of minute men were to be recruited. The Independent Company of Albemarle County thus had a lifespan of perhaps five months.[30]

Under the military district system, Albemarle County was included in the Buckingham District along with Amherst, Augusta (Eastern part), and Buckingham counties. Officers in the Buckingham District Minute Men who had served in the Independent Company of Albemarle County were Charles Lewis, William Lewis, Hastings Marks, Hudson Martin, and George Thompson. Little is known of the activity of this organization; indeed it may have had a shorter history than did the independent companies since Virginia began recruiting for its regular regiments in late 1775.[31]

Several former members of the Independent Company of Albemarle County are known to have served in Virginia regiments in the Continental Army. Samuel Carr, Edward Garland, and James Lewis served in the 9th Virginia Regiment, Charles Lewis, Falvy Frazer, and John Marks served in the 14th Virginia Regiment, and Matthew Jouett served in the 7th Virginia Regiment.[32] No doubt there were many other members of the Company who served in regular regiments or the militia. The Revolutionary War experience for all of these men began with the Independent Company of Albemarle County.

Appendix

The size of the Independent Company of Albemarle County has been understated in a number of publications, beginning with the first transcription of George Gilmer’s commonplace book in 1887.[33] The following is based on an analysis of Gilmer’s original commonplace book.[34] The Virginia Historical Society confirmed that during the conservation process there the individual pages of the Gilmer commonplace book were laminated, then “gathered artificially” into signatures such that the leaf containing pages 11-12 was inserted between the leaves containing pages 10 and 13.[35] (These page numbers have been added since the book was originally written, probably during restoration after the book was reconstructed.) The list beginning on page 10 immediately follows the “Terms of Inlisting.” It begins with an unnumbered list of the 13 officers, then numbers the first 10 privates. The list of privates is continued on page 13, numbered from 119 to 142. At the bottom of page 13 (following the list of privates) is this notation: “Those marked [the mark is a triangle with a cross beneath] had powder. Those marked with the chemical character for gold [i.e. the alchemical symbol, which is a circle with a dot in the center] marched from Charlottesville, or joined us on the way to Wmbgh in order to demand satisfaction of Dunmore for the powder…the 2d May 1775.” The triangle/cross symbol is found only on page 10 while the symbol for gold is found on pages 10 and 13 (only), effectively linking those two pages. The names of privates from numbers 11 to 118 must have been on a leaf which should be between pages 10 and 13, but is no longer a part of the commonplace book.[36] The single column on page 10 records twenty-seven names or lines of text, so the missing leaf, arranged in double-columns as is page 13, would have had the space necessary for the missing 108 names. Therefore the strength of Albemarle’s Independent Company on May 2, 1775 was 155 (13 officers and 142 privates).[37]

Examination of the leaf containing pages 11-12 shows that it contains a different list from that on pages 10 and 13; page 11 is headed “List of Volunteers present at [page torn] 17th June 1775” and contains no numbering of members. Thus its current location in the commonplace book only confuses the determination of the strength of the Albemarle Company.

[1] Rev. Edgar Woods, Albemarle County in Virginia (Harrisonburg: C.J. Carrier Company, 1978), 29-30, 363-364; Irving Brant, James Madison/The Virginia Revolutionist (New York: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1941), 179-180; John Hammond Moore, Albemarle: Jefferson’s County 1727-1976 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia: 1976), 49. The Virginia Gazette (Pinckney), May 11, 1775, mentioned that volunteers from counties other than Albemarle were also known to be on the march, but the surviving record provides little detail about their activities.

[2] These committees were also called county committees of safety. They are called committees of observation herein to avoid confusion with the Virginia Committee of Safety which functioned as the state’s executive arm at this time.

[3] Larry Bowman, “The Virginia County Committees of Safety, 1774-1776,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (hereafter cited as VMBH) 79 (July 1971): 323-324, 335; William E. White, “The Independent Companies of Virginia, 1774-1775,” VMBH 86 (April 1978): 151-152; R.A. Brock, ed., Collections of the Virginia Historical Society, New Series, 6 (Richmond, 1887): 82-85.

[4] See Appendix for a discussion of the size of Albemarle County’s Independent Company.

[5] Brock, Collections, 122.

[6] Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia: The Road to Independence (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977), 3: 3-7. According to John Pendleton Kennedy, ed., Journal of the House of Burgesses 1773-1776 (Richmond, 1905), 223, the governor removed 15 barrels, each containing about fifty weight or 56 pounds of powder, assuming long weight.

[7] Peter Force, American Archives, 4th Series, 2:422.

[8] Scribner and Tarter, Road to Independence, 3: 71.

[9] Brock, Collections, 84; Beverly H. Runge, ed., The Papers of George Washington: Colonial Series (Charlottesville, 1983-1995), 10: 349-350; Gilmer Papers, 13; Moore, Albemarle, 48. While the entire Committee was not available for guidance, a number of its members were also members of the Independent Company, so the decision to march was likely to be consistent with the full committee’s wishes. The April 29 letter to Washington did not reach him until May 3, when he responded via letter. By then the Albemarle volunteers were on the march.

[10] Gilmer’s speech is in Brock, Collections, 77-80.

[11] Peter Force, American Archives, 4th Series, 2:422.

[12] White, “Independent Companies”, 157-158; Scribner and Tarter, Road to Independence 3: 7-8, 111-112; Robert Douthat Meade, Patrick Henry: Practical Revolutionary (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1969), 49; William Wirt, Sketches of the Life and Character of Patrick Henry (Philadelphia, 1817), 137-141.

[13] Wirt, Patrick Henry, 137-141; Virginia D. Cox and Willie T. Weathers, Old Houses of King and Queen County Virginia (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1973), 69, endpaper map. Wirt indicates that Goodall spent a night picketing Laneville; that could only have been the night of May 2.

[14] Scribner and Tarter, Road to Independence 3: 8-10.

[15] Henry’s receipt in Scribner and Tarter, Road to Independence 3:87-88 states that he promised to deliver the money to Virginia authorities for use in purchasing gunpowder for the colony’s defense.

[16] John Burk, Skelton Jones and Louis Hue Girardin, The History of Virginia (Petersburg, Virginia: M.W. Dunnavant, 1816), 4: 12; Virginia Gazette (Purdie), May 5 and 19, 1775. The fact that Goodall’s troop took most of the day on May 3 to travel the 17 miles from Laneville to Doncastle’s Ordinary suggests that they did some recruiting along the way. No doubt Henry did likewise. This is consistent with Burk’s statement that Henry’s party had been joined by volunteers from King William and New Kent Counties. Doncastle’s (sometimes written Duncastle’s) Ordinary, later Bird’s Ordinary, normally provided both food and lodging, though Henry’s force would have overwhelmed both resources.

[17] According to Revolutionary War Pension Application (RWPA) of Edward Mitchell (W23991), National Archives, Washington, DC, the Hanover Company was mounted and thus able to cover perhaps 30 miles in a day. Based on Scribner and Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, 3: 87-88 and Virginia Gazette (Purdie), May 5, 1775, they could not have left Doncastle’s Ordinary on their return to Hanover before early noon on May 4, since Henry had sent Robert Carter Nicholas, Virginia’s Treasurer, then in Williamsburg, an offer of protection and had to await a response. Thus the time required for the Hanover Company to travel the forty-six miles to the vicinity of Hanover Court House was somewhat over a day.

[18] “Memoirs of the Life and Voyages of Doctor Philip Mazzei,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Second Series 9 (1929): 172-173.

[19] Gilmer Papers, 10, 13; RWPA of Benjamin Harris (W7664), National Archives, Washington, DC.

[20] Mazzei, Memoirs, 172. Mazzei probably confused the boundary between Albemarle and Louisa Counties with that of Albemarle and Orange Counties.

[21] Gilmer Papers, 13, 23; RWPA of John Martin (S30563), National Archives; Brant, James Madison, 179-180. Assuming the marchers comprised the same percentage of the total Albemarle Company membership that can be derived from markings in the Gilmer Papers, 10 and 13, that contingent would have numbered less than sixty. Perhaps the turnout among privates was much higher, Mazzei’s memory is to blame for the difference, or volunteers from other counties swelled the ranks to 100. John Martin participated in this march and one in July, and was particular in describing the two different routes followed. Brant’s opinion was that the meeting of the Albemarle and Orange companies had been arranged “at least one day before [the expedition] started.” That seems likely.

[22] RWPA of Benjamin Harris (W7664).

[23]RWPAs of John Martin and Benjamin Harris. Murell provided a supporting deposition to Martin’s RWPA, but did not participate in this march.

[24] Mazzei, Memoirs, 172.

[25] RWPA of John Martin.

[26] Mazzei, Memoirs, 173; Martin RWPA. A pace of fifteen miles per day would have been reasonable for an infantry company of the day. However, the Independent Company of Albemarle County was comprised of fit young men, accustomed to the outdoors, and the circumstances surrounding their march indicates a desire to confront the governor quickly; hence the faster pace.

[27] Mazei, Memoirs, 173.

[28] Mazzei, Memoirs, 173.

[29] Virginia Gazette (Purdie), May 19, 1775.

[30] Brock, Collections, 89; White, “Independent Companies”, 159-161.

[31] Scribner and Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, 4: 80-81, 85.

[32] Woods, Albemarle County, 241, 253, 263 and John G. Gwathmey, Historical Register of Virginians in the Revolution (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1987), 132, 288, 297, 431, 471, 500.

[33] Brock, Collections, provides several lists, made at different times and containing different groups of names; combining those lists yields a total of 108 unique names. Woods, 364-365 contains two of these lists (though with omissions). None of these purport to be complete lists nor does either source estimate the size of the company. Scribner and Tarter, Road to Independence, 3: 48-49 list 13 officers and 10 privates. Michael A. McDonnell, The Politics of War (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 46 gives the size of the Company as 23.

[34] Gilmer Commonplace Book, Gilmer Papers, MSS5:5 G4213-1, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond. Pages 10 and 13 of the commonplace book contain the relevant lists.

[35] Email from Lee Shepard (Virginia Historical Society) to Bill Reynolds, September 6, 2011, “Gilmer Commonplace Book.”

[36] The list in Brock, Collections, 82-84, is a combination of the lists on pages 10 and 13 of the commonplace book and it includes the acknowledgement that “this list is incomplete, a leaf of the original MS. being missing.” Hence the elusive leaf was missing from the commonplace book as early as 1887.

[37] Brock, Collections, 122 indicates that the Albemarle Company’s strength continued to grow, reaching nearly 300 later in the summer of 1775.

3 Comments

Great information on a little known facet of the actions that led to Virginia being second only to Massachusetts in rebelling against British authority and expelling it from the colony.

But a question — and a request for guidance.

You say in the first paragraph of your article “The governor’s action was in response to George III’s direction to colonial governors to take control of arms and powder throughout the colonies, direction which had precipitated the clash at Lexington and Concord two days previously.”

I have been looking into the almost simultaneous actions at Lexington/Concord and at Williamsburg for some time now in an effort to find documentation that anyone in British Government instructed, authorized or even encouraged colonial governors to seize arms and ammunition already in the colonies. So far all I have been able to find is an October 1774 resolution of Parliament prohibiting the export of arms and ammunition to the colonies for six months (“Order of the King, in Council, prohibiting the exportation of Gunpowder, or any sort of Arms or Ammunition from Great Britain,” Peter Force, American Archives, S4-V1-p0881) and a circular letter from Lord Dartmouth to the Colonial Governors instructing them to use their utmost endeavors to enforce that resolution (“Circular Letter from the Earl of Dartmouth to the Governors of the Colonies.” Ibid, S4-V1-p0881.) I have been able to find nothing to suggest that Colonial Governors were directed or encouraged to take control of arms and powder that was already in the colonies.

If you could point me in the direction of documentation which suggests that the Colonial Governors were directed or encouraged to take control of arms and ammunition already in the colonies, I would appreciate it very much. Such documentation would put the almost simultaneous actions of Gage and Dunmore and, perhaps even more significantly, the inaction of the eleven other Royal Governors in in a new light.

Norman,

I found the same sources you mention in your comment. Apparently Gage and Dunmore interpreted their instructions more broadly than they were written when they acted to confiscate powder already in the colonies.

Bill

The day before (20 April), the newly-formed Secret Committee in South Carolina decided on a coordinated raid, which took place on the night of the 21st, to steal arms and ammunition from the State House in Charleston as well as two magazines on the outskirts of the city. They were acting on recommendation of the General Committee, which convened in Charleston for a new session on 19 April and learned of Lord North’s “Conciliatory Plan” to the individual colonies that attempted to weaken the Continental Congress and divide the colonies by picking off individual provinces willing to make a deal with the Crown. The General Committee, recognizing the intentions of North’s plan, decided the province’s military stores needed to be seized, and formed the Secret Committee to carry out the measure. Whatever notice may have been sent from the King for governors to secure these stores was ignored and to the best of my knowledge never mentioned by William Bull, the lieutanent governor and acting governor.