Aside from John and Abigail, what was the best husband-wife duo of the Revolution? Why?

The best husband wife team–better than John and Abigail in my opinion–was George and Martha. We don’t have much in the way of detail about their relationship because Martha burned all their correspondence after Washington died. But we have significant glimpses of how much George shared with her. When John Adams defeated Thomas Jefferson for president in 1796, Martha quietly conveyed George’s congratulations–clear evidence that he had not supported Jefferson.

–Thomas Fleming

I really want to say Benedict Arnold and his wife or Aaron Burr and his Theodosia because their real lives are better than a novel but I will go with George & Martha Washington because their lives were epic too including during the Revolution.

–Robert Scott Davis

Nathanael and Catharine (Caty) Greene. She was the belle of the ball. All the men from Washington on down drooled over her, and Gen. Anthony Wayne courted her after Nathanael died. One jealous Philadelphia matron suggested Caty’s marriage to former ironmonger Nathanael was evidence of her class: “I think I hear the clink of the iron on the anvil at every step she takes.” But Caty was more than a pretty, charismatic face. She provided what we now call venture capital for Eli Whitney’s cotton gin—and some say she helped invent it.

–Don Glickstein

I cast my vote for Mercy Otis Warren and her husband, James Warren. In my opinion, Mercy Otis Warren was the most important woman of the Revolutionary era – she was an essayist, playwright, and historian, taking public political positions that Abigail Adams only voiced to her husband in private. James Warren, while not among the top tier of the founders, was prominent in the opposition to British policy from the beginning of the protests against the Stamp Act until the end of the war. He was active in the Sons of Liberty, served as a representative in and later speaker of the Massachusetts legislature, fought at Bunker Hill, and became president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. He also held a major general’s commission in the state militia and was paymaster general of the Continental Army. He was an important figure, but his wife’s achievements overshadowed his.

–Jim Piecuch

Nathanael and Caty Green. Nathanael Green was arguable one of the most effective of the Patriot generals, not unlike Adams, who was one of the most effective Patriot politicians. Caty Green comes across as intelligent, knowledgeable and as assertive in her own way as Abigail. She traveled to be with her husband several times, something Abigail did not do. And she often did it while pregnant, something Martha Washington didn’t have to deal with when she traveled to visit George.

–Norman Fuss

“Best” is an intriguing adjective—in the eyes of whom? George and Martha, First Couple to be, might be an obvious choice. I take the question to mean which couple were the best for each other. In this capacity, I cast my vote for Peggy and Benedict Arnold. In all my reading, they seem to have been devoted to each other and mutually supportive. Arnold even suggests in a letter that they had a fulfilling sex life as well. As Philadelphia’s ‘first couple” from 1778-1780 they made, in today’s parlance, a great team. In Arnold’s treason, she appears to have been a willing accomplice or at least an accessory. She instigated contact with Andre, introduced Arnold to a Loyalist courier and helped with the correspondence. When Washington appointed Arnold to the command of West Point, Peggy quickly joined her husband, in part because of their closeness but also to continue their efforts in selling West Point. Finally, at the moment of discovery, her wild and noisy behavior helped divert attention so Arnold could make good his escape, whether intended as a ruse or because she felt she had just lost her husband forever. After Arnold fled to the British, she remained with him, continued to support his business and raise their children, all the while treated with some reservations. Even after Arnold’s death she worked hard to pay his considerable debt and maintain his name.

–Steven Paul Mark

Revolutionary war historians are thoroughly versed in the contributions of General John Stark but the general public today is far more familiar with his wife Molly. John was a highly accomplished battlefield commander who invoked the image of his wife in a stirring pre-battle oration at Bennington Vermont that ended with “There are your enemies, the Red Coats and the Tories. They are ours, or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow!”

In addition to this legendary battle cry, Molly’s contemporaries gratefully recognized her for nursing numerous sick and wounded soldiers in her home. Hence her name, not John’s, is more prominently memorialized. There are numerous mountains, parks, lakes, streets, businesses and schools named after her throughout New England and as far west as Minnesota.

–Gene Procknow

Timothy and Rebecca Pickering were a devoted, and relatively unknown, husband-wife duo of the Revolutionary era. Pickering, a Harvard graduate, was admitted to the bar, joined the militia, became adjutant general to General Washington in 1777, then served on the Board of War. He was appointed Quartermaster General of the Continental Army from 1780-1785. Yet, throughout, it was said of him that “family life always formed with him the central object of existence.” Family life was also important to Rebecca, and she unswervingly supported her husband. During the war, Rebecca packed up their three sons (they eventually had ten children) and the little family following Pickering by wagon and coach as he shifted from one location to another. And why did she do this? Rebecca had no family in America, she loved and respected her husband, and, as she wrote Timothy in 1780, “Your convenience is right for my happiness.”

For unrestrained mutual devotion, as demonstrated by the wonderful love letters between the two, consider Henry and Lucy Knox. During the Revolutionary War General Henry Knox was the masterful commander of the Continental Army’s artillery. It can be argued, however, that he never assumed command of his wife, Lucy—nor would she have permitted him to do so. Indeed, soon after their marriage, the independent Lucy wrote her new husband that “I hope you will not consider yourself as commander in chief of your own house, but be convinced…there is such a thing as equal command.” Nevertheless, Henry and Lucy Knox adored each other; their correspondence is peppered with such phrases as “My dearest dear friend,” “Your anxiously tender husband,” and “My dearest hope and only love.” Regrettably, Henry Knox suffered an untimely death in 1806. Lonely and sad, Lucy— in poor health, with little money—passed away eighteen years later.

–Nancy K. Loane

If “best” means the duo that best aided the American Revolution, I am sure there must have been countless nameless men who bore arms while their spouses at home made bullets. But of those with whom I am familiar, I opt for Joseph and Esther Reed. He played an important role in Pennsylvania’s insurgency, served in the army and as Washington’s secretary, played a crucial role in the Continental army’s escape after the Second Battle of Trenton, sat in the Continental Congress, and was the chief executive of his state for three years. She organized the Ladies Organization in Philadelphia in 1780 and published a broadside urging women not to purchase unnecessary consumer items, but instead to donate the money that they saved to aid the soldiery in the Continental army. Altogether, her campaign raised nearly $50,000 in four states.

–John Ferling

Henry and Lucy Knox. Married at 23 and 17 in 1774, they were a youthful, smart, committed, and virtually inseparable couple. Henry’s father had abandoned him and Lucy’s Loyalist parents disowned her and fled for England, so they leaned on each other heavily. Lucy was very supportive of Henry. When they were apart, Henry fretted about Lucy’s safety and wrote her lengthy letters. When they were together, they seemed quite close. You can’t help but sense the deep devotion and affection between the two.

–Daniel Tortora

Besides John and Abigail, my favorite power-couple of the War was Paul Revere and his second wife, Rachel Walker. The two met outside his silver shop and fell deeply for each other, and he wrote her love poems on the back of receipts. On the night of the infamous “midnight ride”, Rachel worried about him so much that when he didn’t come home when he approximated, she gave a member of the Sons of Liberty £125 to track down her husband. Adorable.

–Jerome Palliser

I decided to look for a couple in which the wife did more than assist her husband in his work, even breaking out of the traditional role of a housewife. My choice is therefore Mercy and James Warren of Plymouth, Massachusetts.

James was a Massachusetts sheriff and legislator who rose steadily among the province’s Whigs until in 1775 he was President of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress and then Speaker of the Massachusetts General Court. At the time, Massachusetts was the main theater of the Revolutionary War. James assisted that military effort not only as a senior member of the local government but as first paymaster general of the Continental Army. He remained active in Massachusetts but never worked at the national level.

Mercy Warren was more unusual since she was a rare female writer on political topics. In the 1770s she published plays satirizing Crown officials like The Adulateur and The Group, her authorship an open secret in Massachusetts even before she collected her poetic writings into a book. In 1788 Mercy wrote Observations on the New Constitution, a pamphlet opposing ratification of the new document without a Bill of Rights, and she collaborated with James on other Anti-Federalist essays. In 1805 Mercy published her three-volume History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution; like the Warrens’ politics, her history (especially the footnotes) slanted toward the Jeffersonian party, and that damaged her friendships and later reputation.

Mercy Warren also raised five sons, maintained correspondence with other women of her class (including Abigail Adams, whom she intimidated at first), and produced eye-popping needlework. In other words, she did everything a genteel housewife was expected to do—and she became one of the period’s more influential political authors.

–J. L. Bell

At the risk of cliché, the runner-up “Best Husband-Wife Duo of the Revolution” title would have to belong to George and Martha Washington. Usually not an outgoing person, Martha rose to the occasion of being a social hostess when needed and carried out her duty to public service commitment such as knitting socks for Continental Army troops and raising clothing and food donations. But most importantly, Martha sought to be with the Commander-in-Chief at his war camps throughout the entire Revolution. Her visits made George Washington noticeably relaxed, Mercy Otis Warren noticed. Nathanael Greene said of the duo, “They are happy in each other.” Mount Vernon historian Mary Thompson has estimated that Martha visited George 52 – 54 months out of the 103 months of the war. In other words, literally during half the war, Martha brought some serenity to her troubled husband with her mere presence.

–John L. Smith, Jr.

I would say Nathanael and Catherine Greene. They seemed very devoted to each other, and Catherine was a vivacious, attractive woman who was not content to stay at home and was able to distract Greene, as well as Washington and other officers, from the drudgery of their military toils. After Nathanael died tragically in 1786, Catherine stepped up and handled his estate and obtained reimbursement of Nathanael’s out-of-pocket expenses from Congress. (I believe Benjamin Franklin tried to hit on Catherine when she was a teenager in Rhode Island; she was raised on Block Island.)

–Christian McBurney

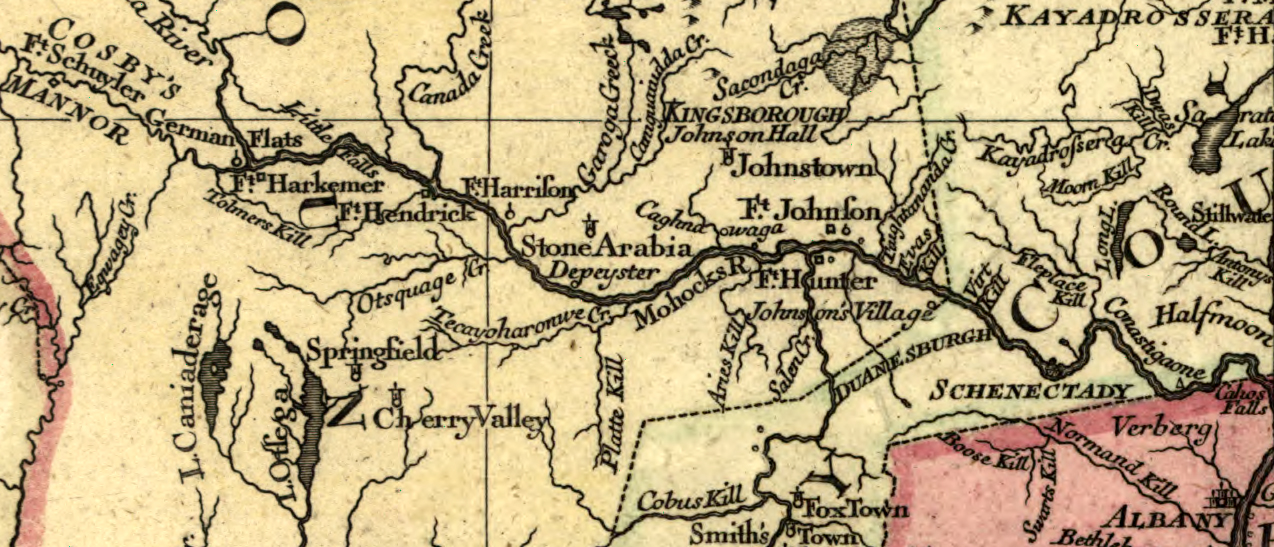

I submit Philip Schuyler and Catharina van Rensselaer Schuyler for consideration. This Albany, New York couple had many responsibilities. Philip commanded the Northern Department of the Continental Army. Congress charged Schuyler with invading Canada, a task he undertook only when ordered because he felt his men ill-equipped for the task. Catharina did her best to keep Philip going when his ague struck. She also managed their Albany and Saratoga estates and cared for their 7 children, three of whom she gave birth to between 1774 and 1781. Finally, this power couple played the role of gracious host and hostess to a defeated John Burgoyne and his retinue. This role must have been difficult for the Schuylers. Philip’s planning (along with Benedict Arnold’s bravery) had played a major role in the Patriots’ victory, but he did not receive credit. Also, Burgoyne burned down their Saratoga estate during the Battle of Saratoga.

–Elizabeth M. Covart

This might be an obvious choice but I think George and Martha Washington are at times underrated in that regard. The lack of significant correspondence between the two has no doubt contributed to that, but Martha sacrificed greatly for the benefit of the new nation and contributed in her own way during her numerous camp visits.

–Michael D. Hattem

The best husband-wife duo might be the best kept secret held in plain sight: Thomas Jefferson and Martha Wayles Skelton Jefferson. Many think that historians don’t know enough about Martha to make informed observations about her alone, much less engage in analysis about her significance in Revolutionary affairs. Most Jefferson historians dismiss, or just disregard, her, just as they do her mother. But as a historian of first ladies, and First Ladies, I can happily report that rarely have so many been so wrong about so much regarding such a subject. Forget the musical 1776. Martha was a savvy, literate, even pious businesswoman who learned from her hard-nosed father, and knew, more than almost anyone around her, the nature of freedom, given that she lived and worked daily with close relatives whose enslavement, compared to her liberty, could only be explained, with any logic, by the staunchest of Calvinists—only the law and outrageous fortune separated their conditions. Yet she, who owned vastly more property than her husband, managed their holdings during the years that made Jefferson who he was. She determined crop rotation as easily as she could play Methodist hymns or discuss physiocracy. Martha Jefferson was the ultimate realistic whom could allow Thomas to dream; she saw and dealt with the world as it was, while her husband thought of the world that could be. And became. But without her, there would have been no him, and, consequently, no us.

–Taylor Stoermer

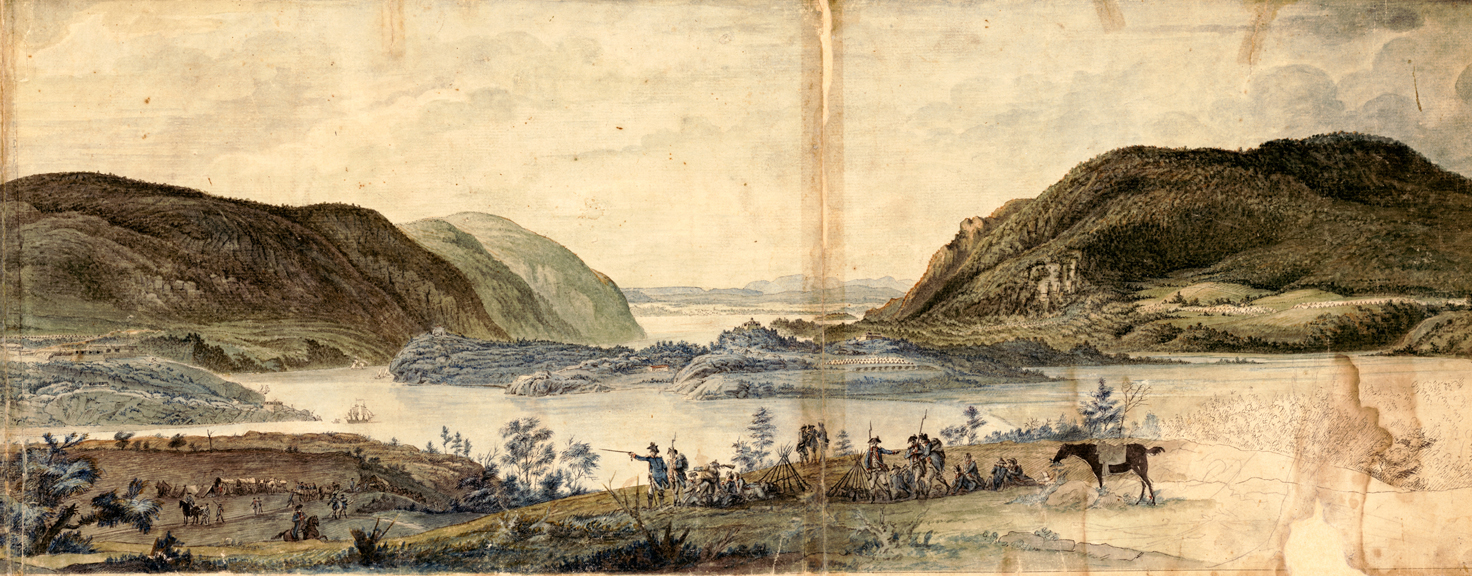

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: “The Washington Family” painting by Edward Savage. Current location: National Gallery of Art]

6 Comments

I seem to never disagree with John Ferling. He has chosen my absolute & sentimental favorites, Joseph & Esther Reed. Individually & as a couple, theirs is a story worth much closer study.

Just a thought, but there were more than just Rebel couples involved in the American Revolution. Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel, Baron/Freiherr zu Eisenbach and his wife Frederika Charlotte Louise von Massow, Baroness/Freifrau Riedesel zu Eisenbach have a fascinating story from the opposite side well worth sharing. From the Burgoyne Campaign on, their journey took them across the Northeastern parts of North America and into and out of the lives and stories of many other fascinating people and events.

John and Sarah Livingston Jay! She was the daughter of a Signer and he was, among many other positions, an ambassador who signed the Treaty of Paris and the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Their lengthy correspondence has been preserved and reveals a loving, useful, and incredibly patriotic family.

I believe Sarah Livingston Jay was the daugther of William Livingston of New Jersey, not Philip Livingston, the signer. Philip woudl have been her uncle I think.

How about Gil and Lana Martin of “Drums Along the Mohawk” written by Walter D. Edmonds in 1936 and characterized by both Henry Fonda and Claudette Colbert in the 1940 screenplay! While both actors obviously did not live during the Revolution, they certainly represented and portrayed so many couples living during that time! Reading the classic and seeing the movie show how difficult it was for frontier couples to live and survive!

John Pearson

I concur with the submissions for the Washington’s, Greene’s, Warren’s, Knox’s and Revere’s.

Among the “best” husband-wife duos, we should not overlook John Dickinson and his wife Mary (Polly) Norris Dickinson. Theirs lives exemplify the best of the vibrant cultural, economic, political and civic traits of the Quakers of from the distinct Mid-Atlantic/Delaware Valley sub-culture region.

An energetic republic needed an educated citizenry (men and women). Their greatest legacy derived from the donated land and library (the Norris family library was one of the largest in the colonies) that became the first university originating in the new United States, Dickinson College, founded by Benjamin Rush (originally named John and Mary’s College)