As we know from our history books, the War for Independence began with the shots fired at Lexington and Concord. Those shots required gunpowder, a substance that was in short supply throughout the colonies. In 1775 there was only one American gunpowder mill, the Frankford Mill in Pennsylvania, and it was turning out a miniscule amount compared to what would be needed to wage a successful war.[1] In addition, this mill was not turning out the high-quality powder needed for artillery use. If the Patriots were going to have any chance of victory, the colonies needed to step up production or import it. Had it not been for the French assistance in supplying the Americans with gunpowder from 1776 throughout the war, American forces would not have been able to fight and win the battles that they did.

Gunpowder is a mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate that must be combined in specific ratios. While this sounds simple enough, it must be remembered that in 1775 the state of chemistry was rudimentary. Potassium nitrate itself is a compound of nitrogen and potassium, neither element of which had been identified at that point in time.[2] What they did know was that what they called “nitre” was needed, which, in some recipes, involved soaking soil in urine from both animals and humans, and then allowing it to dry. The dried urine-soil was then boiled to produce saltpeter. Not all recipes agreed with this method which added to the problems in making gunpowder. Unfortunately this required half a year or more to produce nitre-bearing soil and created a bottleneck in the production of gunpowder in America.

When the War for Independence started American supplies of powder were what they had gathered from Royal sources or their own local supplies. The amount was not enough to sustain an army in the field. While Congress was hopeful that they could establish enough mills to create their own self-sustaining sources of gunpowder, they also decided to seek additional supplies from overseas which meant European suppliers. The Journals of the Continental Congress are full of references to purchasing gunpowder in the West Indies. To do so meant selling American goods which involved adjusting the rules under the Association agreement of 1774. As several congressional delegates noted, gunpowder was needed or else the whole enterprise was lost. A Secret Committee was set up on September 19, 1775 to contract and agree to importation of gunpowder not to exceed 500 tons.[3] In addition, saltpeter and sulfur could be bought to make up part of the 500 tons.

This illustrated just how desperate the Continental Congress was for gunpowder as well as the poor state of affairs in gunpowder manufacturing in the colonies. It also brings us to a question about why gunpowder manufacturing was so miniscule for colonies that had been involved in a series of wars between Great Britain and France for almost a century as well as an on-and-off-again conflict with Native Americans along the frontiers. The first known colonial powder mill was mentioned in an order of the General Court of Massachusetts on June 6, 1639.[4] Then as it was during the Revolution, the production of saltpeter was recognized as a barrier to gunpowder manufacturing. Steps were taken to alleviate that situation and small scale gunpowder manufacturing were in operation throughout the remainder of that century and the 18th until the Seven Year’s War.[5]

The burgeoning trade between Great Britain and her colonies in North America that flourished from the 1750s onward apparently included gunpowder as one commodity that was cheaper to make in Britain than in the colonies. France found her gunpowder manufacturing had slipped as well by 1774, partly due to the importation of cheap saltpeter from India, a trade controlled by Great Britain. Fortunately for the French and later the Americans, Antoine Lavoisier was appointed to head France’s Gunpowder Commission where his recommendations quickly brought France back to full production of both gunpowder and saltpeter. Saltpeter again was the key ingredient for both nations. Trade with the American colonies was controlled by Britain through the Navigation Acts and industrial production discouraged by various laws.[6] One of the results of this was that the colonists allowed their powder mills to decay and closed them as it was far more convenient and cost effective to import gunpowder from Britain. The result would be that the colonies found themselves in dire need of powder mills in 1775.

Due to the nature of the colonial governments and their relationship with the Continental Congress, it was felt by many that gunpowder production was something left to the state governments. At first production was renewed and several thousand pounds produced, but the lack of available saltpeter quickly throttled back production. Only the arrival of imported saltpeter allowed some mills to continue production, but that varied on what ports the saltpeter arrived in as well as the difficulty in obtaining contracts from Congress, who was purchasing most of the saltpeter. In addition, the quality of the gunpowder from these hastily erected mills ranged over a wide margin. In Massachusetts both Generals William Heath and George Washington noted the poor quality of that gunpowder.[7] The result was one which would last throughout the entire war, that of a persistent demand for gunpowder which would never be met by domestic production at any point in the conflict.

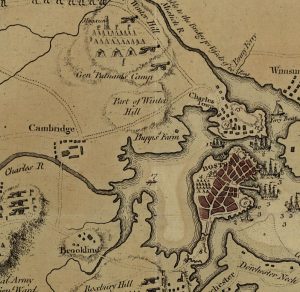

The shortage of powder was felt early in the conflict; one factor (not necessarily a main one) in the British victory at Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775 was the limited amount of gunpowder possessed by the Patriot forces.[8] In late April, General Artemas Ward, commander of the Massachusetts Bay forces besieging Boston, had taken stock of the powder in his army’s control and found it to be woefully short prompting that colony’s Committee of Safety to request gunpowder from the towns and villages.[9] This situation improved, but in August another inventory ordered by George Washington found supplies to be so short that only a half pound per man could be furnished. Gen. John Sullivan said that Washington on hearing of this report did not utter a word for half an hour.[10] Requests were sent to colonial governments for gunpowder which arrived in short order. We can only speculate on what might have happened had the British made an attempt to break the siege before that critical shortage of gunpowder was eased.

Desperate for powder, no matter where it was located, both Washington and Congress eyed the British powder magazine on the island of Bermuda. Unbeknownst to each other both undertook separate operations to seize the powder. Governor Bruere of Bermuda described the raid organized by Congress on the powder magazine as follows:

I had less suspicion than before, that such a daring and Violent attempt would be made on the Powder Magazine, which in the dead of night of the 14th of August was broke into on Top, just to let a man down, and the Doors most Audaciously and daringly forced open, at the great risk of their being blown up; they could not force the Powder Room Door, without getting into the inside on Top. They Stole and Carried off about one Hundred Barrels of Gun powder, and as they left about ten or twelve Barrels, it may be Supposed that those Barrels left, would not bare remooving. It must have taken a Considerable number of People; and we may Suppose some Negroes, to assist as well as White Persons of consequence…

The next morning the 15th instant (of August), one sloop Called the Lady Catharine, belonging by Her Register to Virginia, George Ord Master, bound to Philadelphia, was seen under Sail, but the Custom House Boat could not over take Her.[11]

The “Negroes” and “White Persons of consequence” the governor referred to were people on the island of Bermuda who assisted the Americans steal the powder. The ship sent by Washington arrived weeks later only to find the powder gone.

The campaign in Canada, threats along the western frontier from Native Americans, the looming expectation of a major British attack at New York, and the needs of naval forces all meant that even more gunpowder would be needed. The new powder mills would fall short of expected needs in 1776 and as the initial supplies of saltpeter ran low, only imported amounts allowed the mills to produce any real supplies of gunpowder at all. While sources disagree on the percentage of powder produced by these mills during this period compared to imported amounts, they do agree that without imported or captured gunpowder the Continental Army would have run out several times during that year’s campaigns. This situation was made dire by the loss of supplies at Forts Washington and Lee in New York in November of 1776 where over 400,000 rounds of ammunition were captured at Fort Lee alone.[12]

Fortunately for the American cause, interests in Europe were such that aiding the Americans was seen by several nations as a means to weaken Great Britain. The Dutch were more than happy to trade with American ships at St. Eustatia throughout the conflict until the British attacked and captured the island in 1781.[13] Gunpowder from Europe, mainly French, transferred hands and was sent to America as well as saltpeter. Prior to the French agreeing to supply clandestine aid to the Americans, enterprising French merchants had already arranged to ship large quantities of arms and gunpowder through the West Indies despite the obvious violations of international law.[14] The various colonial legislatures had also been busy arranging for gunpowder purchases as well. This was fortuitous because the large losses by the Continental Army left little available for the colonial militias.

The clandestine aid from France arrived at a time when it was desperately needed. The powder mills in the colonies began to run out of saltpeter in 1777 and production fell abruptly.[15] Silas Deane, the Continental Congress’s representative in France served as a middleman and arranged for the shipment of almost a million pounds of gunpowder. Washington’s shortage of gunpowder had led him to issue orders prohibiting its wastage in 1775 and he had to repeatedly reissue similar orders throughout the war despite the French supplies of gunpowder.[16] Estimates place the percentage of French supplied arms to the Americans in the Saratoga campaign up to 90%, but the gunpowder used was for all practical purposes supplied by the French entirely. The critical shortage of gunpowder played a major role in the continued stalemate in the north in 1780 as General Knox’s estimates of the powder needed for a siege of New York City was more than the Continental Army could reasonably expect to have available that year.[17]

The inability of the Americans to manufacture an adequate supply of gunpowder was just one of the many critical problems the rebels faced during the Revolutionary War. Domestic production, though promising at first, never came close to fulfilling their needs. This shortage created a situation that necessitated an American search for foreign supplies as well as revealing the necessity of foreign aid. Fortunately, the conflict between Great Britain and her rebellious colonies created a situation that other nations, particularly France, exploited in order to hurt Britain’s place in the balance of power. Had it not been for the French assistance in supplying the Americans with gunpowder from 1776 throughout the war, American forces would not have been able to sustain their war effort and win the battles that they did, and ultimately the war and independence.

[1] David L. Salay, ”The Production of Gunpowder in Pennsylvania During the American Revolution,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 99, No. 4 (Oct. 1975), 422.

[2] J.L. Bell, “How Not to Make Saltpetre,” Boston 1775, April 3, 2013. http://boston1775.blogspot.com/search/label/gunpowder (accessed August 9, 2013).

[3] Library of Congress, Journals of the Continental Congress, September 19, 1775. http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc00282)): (accessed August 8, 2013).

[4] Records of the General Court of Massachusetts, quoted by J.L. Bishop, History of American Manufacturers (Philadelphia: Young, 1864), II, 24.

[5] Orlando W. Stephenson,”The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jan. 1925), 271.

[7] Jack Kelly, Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, and Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World (New York: Basic Books, 2004), 162.

[8] Robert Middlekauf, The Glorious Revolution: The American Revolution 1763-1789, rev. ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 297.

[9] Erna Risch, “Supplying Washington’s Army, Center of Military History, US Army” (Washington, D.C.: US Army, 1981), 5.

[10] John Sullivan, Letters and Papers of Major-General John Sullivan, ed. Otis G. Hammond, 3 vols. (Concord: New Hampshire Historical Society, 1930-39), 1:72.

[11] Letter Governor Bruere to Lord Dartmouth, August 17, 1775 and September 13, 1775. William Bell Clark, editor, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 1 and vol. 2, (Washington, DC: U.S. Navy Department, 1964, 1966), 91.

[12] John Ferling, Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 154.

[13] J. Franklin Jameson, “St. Eustatius in the American Revolution,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Jul. 1903), 689.

20 Comments

Nice bit of work on the powder situation with the colonies. If I may be so bold as to add a bit of info regarding the shortage of powder in Massachusetts following the Battle of Bunker Hill, it seems that one of the interesting tidbits to be learned from examining the letters of John Stuart in June 1775 was that a powder shipment for Savannah was expected in July and that Governor Wright intended the cargo for Cherokee and Creek Indian allotments. At that time, the colonists suspected Stuart of stirring up trouble with the Cherokee and rumors (likely false at that point) ran roughshod.

In any event, the Committeemen from both South Carolina and Georgia waylaid the Governor’s ship and confiscated 16,000 lbs of powder of which 7,000 went to South Carolina and 9,000 went to Georgia. Now, the Georgia Committee had already confiscated the state’s supply of powder and, with this addition, had some and to spare. So, when Drayton brought word of Massachusett’s shortfall, they sent a ship with 5,000 lbs to Philadelphia, of which, at least a portion is thought to have gone with Arnold to Canada.

Yep, true believers them Georgia boys. 🙂

Wayne,

Thanks for the compliment. I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The Georgia situation was remarked on by O.W. Stephenson in an article written in 1925, “The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776.” It is in the American Historical Review, vol. 30, no. 2.

Please let me know of any sources you have on this situation in Georgia and South Carolina so I can add to this article in future endeavors. A lot of the powder was sent to Washington after his discovery of the critical shortage of powder in August 1775. He must have gotten enough to equip the two pronged attack on Canada. I think in hindsight he might have wished he hadn’t received enough to allow him to make that decision.

For the Gunpowder stories from GA and SC, I would look to:

1. Memoirs of the American Revolution, John Drayton

2. The History of Geogia, Hugh McCall

3. Documentary History of the American Revolution, Robert Gibbes (Wright v Gage, June 27, 1775)

4. Letters of Joseph Clay

For some more recent secondary sources:

1. Militiamen, Rangers, and Redcoats, James Johnson

2. The American Revolution in Georgia, Kenneth Coleman

There is a James Habersham biography that I have not read but I suspect it will focus on the events of 1775 in which he was a key player.

Thanks Wayne! The more sources we have available to use the better a job we can do to construct a deeper understanding of the events of the past.

A portion of the powder for the Canada campaign came from the powder mill that Judge Robert R. Livingston built in the summer of 1775 on his Clermont land. He was able to produce some powder but the real value of his mill came from the remilling of damaged powder found at Fort Ticonderoga and in the city of Albany. He sent the good powder back to Schuyler while he was planning for the attack. Livingston’s mill blew up shortly before he died in December of 1775. His son, John, rebuilt that mill and another mill in Dutchess county shortly there after.

That’s consistent with the record on American gunpowder manufacturing. The biggest problem the Americans faced was the lack of nitre which itself was due to the imperfect knowledge of the era and colonies on the production of saltpeter. Gunpowder production could have resulted in a self-sustaining supply at some point during the war had they known how to produce saltpeter, but even then they would have had problems with sulfur production.

Any way you look at it, the colonies went into a war very unprepared to fight it and desperately needed foreign aid of many kinds. I’ll be following up on this article with another one on how the Continental Congress sought foreign aid. I’ve already covered the establishment of the Committee of Secret Correspondence in an earlier article last month.

Right you are Jimmy. I think one of the myths of the Revolution is that the alliance with France relieved the Continental Army’s shortages in weapons and materiel, including gunpowder. The alliance certainly provided for many of these items but not nearly enough, as you astutely point out. In the campaign for the Hudson in 1779, like the operations around New York in 1780 that you mention, the Continental Army remained critically short of gunpowder, among many other items, and Washington issued orders for its conservation. In this campaign, Washington skillfully husbanded his resources by using economy of force operations to knock the British onto the defensive. Thanks for an interesting piece on an important topic.

Thanks, Mike. This brings up the global aspect of the conflict and the goals of the French, Spanish, and Dutch regarding the US. I’m working on this for future articles. The War of American Independence was far more complex than most people think. So much of the conflict was dictated by decisions made in European capitals and could very easily had a different outcome.

Gave you a credit on

What’s New on the Online Library of the American Revolution.

Thank you very much for the credit. Always glad to share the knowledge.

I enjoyed your 2013 article on the shortage of gunpowder during America’s War for Independence. I am submitting a similar article soon on the Continental Powder Works which was the first congressional approved, state funded powder works in our nation, located in Chester County Pennsylvania. The mill was located just eight miles from the historic winter encampment at Valley Forge. I must admit, I did not read your article until researching article guidelines to submit my piece, but the two articles should compliment each other, nicely. As most readers know, Washington was very frustrated by the lack of powder and voiced this frustration through many of his early letters.

So very glad to have found this site. My husband and I are military history historians and teachers.

I use the site for my students when we reach the period on the Revolution. One of my objectives in teaching the survey courses is to develop an appreciation of history in students. Informative sites like this with fact checking help to show a wider range of history within a specific period which can engage students on a different level than a textbook. More than one student has read through the articles fascinated at the complexities involved in the Revolution.

An interesting occurrence created by lack of gunpowder in America at this time was the establishment of the du Pont Powder Works along the Brandywine River in northern Delaware. E.I. du Pont founded his gunpowder mills in 1802 at the urging of Tho. Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, de Marques de Lafayette and others. They knew that E.I. du Pont had studied the best practices of gunpowder manufacturing in the French powder yards in the 1780s, and knew first hand of course the conundrum Washington had experienced in the revolutionary war facing the British with critically short gunpowder supplies. With the creation of the du Pont Powder Works, this problem was largely allayed for later U.S. military engagements . Today many of the structures of this former powder works are beautifully preserved near Wilmington as the Hagley Museum and Library. There you can learn the powder making process and get a great sense of what was like as a 19th Century powder worker.

Most people don’t realize, you also had the Continental Powder Works along French Creek in Chester County Pa. not 15 miles from Valley Forge. The CPW was congressional funding. The powder works had a short production life going into operation in summer of 1776, but was destroyed by suspected arson in March 1777. The ruins were discovered and destroyed more by the British patrols along French Creek during the raid and destruction of the Valley Forge in September of 1777, three months before Washington’s occupation at Valley Forge during the winter and spring of 1777-1778.

Scott Houting

U.S. Park Ranger

Valley Forge National Historical Park

Hello Scott, I just came upon your post. I am a history buff, not a scholar. But I have a few questions if you don’t mind. Who owned the CPW?, When was it created? Who worked there? Was there a contract from Congress for powder like there was for the Frankford Powder Mill? Approximately how much powder was produced by the Mill? What British regiment helped destroy the site? Who was in command near Valley Forge? Was it Is there a historical marker for it today?

Thanks in advance for any information.

The Statia connection was always quite interesting, especially with recent scholarship regarding importation of foodstuffs and animals from the North American colonies to the British west Indies and in fact to all of the West Indies.

Given the return on one acre of cane vs an acre of cabbage, it made economic sense

to purchase foodstuffs from North America. Cape Cod produced dried stock fish on an industrial scale for Europe and a cheap inferior grade called India flake for the West Indies (see COD by Kurlansky), while the Carolinas produced salt herring in Edenton and swaths of rice,originally West African species oryza g. (see BLACK RICE by Carney). Middle colonies supplied pork products and Rhode Island I believe horses.

Although the British parliament tried to ban trade between colonies, American colonies provided food which also helped allay slave revolts (even today dried cod is the national dish in Jamaica, an island surrounded by a plethora of seafood). With the upcoming naval blockades, Caribbean planters of many nationalities were fearful of revolts that would come with hunger. So even British planters would come to Sint Eustatius to barter and trade with American smugglers who would trade for arms and powder.

While the Dutch were neutral the entrepôt was safe. With the entry of the Netherlands into the war, things changed and Admiral Rodney under cover of Dutch colors entered and occupied the port imprisoning locals and even brits there who had been trading. And enriching himself. The irony is that his fleet was supposed to be guarding the capes at the mouth of the Chesapeake. They weren’t there so the French won the Battle of the Capes on September 5,1781, blocking British reinforcements, and thus Yorktown fell a few weeks later ending the land war on a grand scale.

The gunpowder was fascinating as even in the debates in Parliament regarding the crisis in America mention that there was no more than six months worth of powder in America.

Came onto your article quite late but enjoyed it nonetheless

How can I learn something about the history of some powder mills on the Exeter river in Exeter, NH, circa 1776? I know there was a least one on a diversion channel at a place called King Falls.

I’m currently writing a book on the last explosion at the hazard powder mills in Enfield CT – as part of the story I’m currently researching Allen Loomis ( who founded the original mill ) and his connection to Colonel laflin – who began making salt peter in 1764 ( or thereabouts ) in Westfield MA –

References mention he supplied potassium nitrate to the militias in new England – but I’ve yet to find a mention of WHO purchased the ingredient – and mixed it to create gunpowder.

Any references anyone has come across that might help clarify TO WHOM his salt peter was sold would be wonderful…the search continues…

Does anyone know if any of the saltpeter works on Market Street in Philadelphia still exist or even where it was if it is no longer around?