It is considered the oldest, continuously serving military unit in the United States. The 1st Company, Governors Foot Guard has as much a storied history as the state that it serves. It came into existence in 1771, when the Connecticut General Assembly approved a petition that had been submitted by a group of prominent Hartford citizens to form an independent militia company. Among them was Samuel Wyllys, the son of the secretary of state and future Continental army colonel. The petition created “a distinct military company by the name of the Governor’s Guard…consisting of sixty-four in number, rank and file, to attend upon and guard the Governor and General Assembly annually on election days and at all other times as occasion shall require, equipped with proper arms and uniformly dressed.”[1]

It would hold the name “Governor’s Guard” until 1775 when a group of New Haven citizens, among them Benedict Arnold, petitioned the General Assembly to raise a second company in that city. It would be known as the First Company, Governor’s Guard for only two years when in 1778, with the organization of the Governor’s Horse Guards, they again modified their name to its current one, the First Company, Governor’s Foot Guard.

It has been a long held tradition that the unit played a very minimal role during the Revolutionary War. Its official history, published in 1901, only mentions two occurrences where they believed that the company played a significant role during the conflict. The first being in the fall of 1780, where they provided a military escort to two French commanders, Gen. Comte de Rochambeau and Adm. de Ternay through the streets of Hartford where they were to meet with George Washington at the State House. They referred to it as “the most interesting and imposing event in their entire history.”[2] The second event was the company’s seemingly uneventful participation in the Saratoga Campaign.

During the unit’s centennial commemoration an address was given by Col. Henry C. Deming in which he recounted the event:

It was the darkest hour of the Revolutionary struggle. Burgoyne had broken through the gates of Canada, swept out from St. Clair from Ticonderoga, captured and dismantled all the fortresses from the foot of Lake George to the head waters of the Hudson, and was in triumphant progress to join Sir Henry Clinton and cut off New England from New York…All the troops in the Eastern States were rallied to prevent the consummation of the fatal design. The Guard was not obliged to go. They were not liable to the draft. Their duty was limited to guarding the Governor and the General Assembly. Under no circumstance could they be forced to the front, unless the governor went in person. But…the Guard unanimously resolved to go and actually went, under Captain Jonathan Bull, and while an advanced guard of reinforcements hurrying to Saratoga, they were crossing the Rhinebeck Flats they were met by a messenger with the joyful intelligence that Burgoyne had surrendered, and wheeling about marched with alacrity, it is presumed, for the banks of the Connecticut.[3]

According to Deming, the company, as volunteers, had marched over ninety miles, only to be turned back, disappointed at not reaching the scene to participate in either of the battles of Saratoga. Only until recently, that was all that was known about their participation in the campaign.

The real story is that the Governor’s Foot Guard played a much larger role in the Saratoga campaign than anyone had previously reported. In fact, they may have actually played a larger role in the war than previously believed. While researching another topic, I came across the pension application of John Roberts. According to his application, Roberts was born on September 15, 1759 and resided in Hartford at the outbreak of the war. He never states his involvement in the Governor’s Guard until 1777, but he mentions serving under officers that were part of the company. For his first term of service, Roberts, in May 1775, joined a company of volunteers in Hartford under Lt. William Knox, a member of the Governor’s Guard, and marched to Fort Ticonderoga in New York. There they escorted British prisoners of war back to Hartford. Roberts remained as a prison guard until the following February, where he assisted the movement of military supplies to the Continental army then engaged in the siege of Boston.[4]

Roberts states that in June 1777 the First Company volunteered as a unit and was sent over sixty miles away to the Connecticut coastal town of Fairfield. There they served for three months, where they were “constantly employed in guarding the sound coast.” Discharged on the first of September, they returned to Hartford.[5]

By the last week of September, a dispatch rider arrived in Hartford carrying requests for reinforcements from Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam, the commander of Continental forces along the Hudson River, then stationed at Peekskill, New York.[6] It was feared by Putnam that he was about to be attacked by a British force under the command of Sir Henry Clinton who was then moving up the Hudson River in order to cooperate with Gen. John Burgoyne.

It is here that we can join Deming’s narrative of events. His assertions thus far were correct; the company, despite not being obliged to go, volunteered their services during the fall of 1777. However, it was not to reinforce Saratoga, but to aid Peekskill. Under the leadership of Capt. Jonathan Bull, Lt. William Bull and Ens. James Tiley, they joined a drafted militia brigade under the command of Brig. Gen. Erastus Wolcott.[7] After marching over a hundred miles, they arrived at Peekskill on October 9, two days after the British captured Forts Montgomery and Clinton, just across the river.[8]

According to Roberts, when they arrived they did not serve with the other militia units. They were instead attached to the 3rd Connecticut Regiment, part of the Continental army.[9] This was probably because the regiment’s colonel, Samuel Wyllys, was the prime organizer of company and was its commander before the war. He apparently wanted his company to serve with him.

After the British established a base at Fort Clinton, they began launching naval raids up the river in attempt to help Burgoyne, who was then engaged near Saratoga. Since its capture, along with Fort Montgomery, Putnam had been moving his force northward along the east bank of the Hudson in order to observe British movements.

On October 16, a British force landed at Kingston, the wartime capital of New York, about sixty five miles north of Peekskill. They marched inland, captured the city and set it ablaze. Instead of marching to Kingston, Putnam, learning of Burgoyne’s surrender at Saratoga, halted his force. That same day he issued a general order informing his men of the surrender and “Congratulates the troops and orders them to Halt and Remain … untill further orders and Cook Provisions & Refresh them Selves …” [10]

The next day, George Clinton, the governor of New York, sent requests southward to Putnam for assistance. He feared the burning of Kingston was only the first of several intended British targets. He might have also been nervous that they might make an attempt to free Burgoyne’s captured army. Putnam responded quickly by sending most of his force northward towards Rhinebeck, located just opposite of Kingston, the very same day.[11]

The 3rd Connecticut Regiment, with the Governor’s Foot Guard, marched about six miles in the lead of the main force. While we cannot verify that the First Company was in the advance guard, like Deming asserted, we now know for sure that at least their regiment was in the lead.[12] They were also advancing, despite having heard of Burgoyne’s surrender the previous day. This was in contradiction to Deming’s statement because he stated that upon hearing the good news, they turned around and headed back to Connecticut. They did not turn around, but instead pressed ahead to Rhinebeck where they arrived on the 18th. There they were able to view the British force that was still on shipping in the river.[13] Roberts noted this in his pension application that at this time they were “employed watching the movement of the Enemys ship board up the river.”[14]

They would remain here for about a couple days, until the British commander, learning of the surrender at Saratoga and realizing that he was basically surrounded by thousands of American troops, withdrew first towards Fort Clinton and then eventually back to New York City.[15] The Governor’s Foot Guard retired southward with the rest of the force back to Peekskill where they were discharged and sent home in early November, having served for about a month.[16] This would be the first and last time that they would outside the border of Connecticut.

The service of the First Company, Governor’s Foot Guard along the Hudson River during the latter parts of the Saratoga Campaign has been completely forgotten. It might be because they did not participate in the battles of Saratoga or because the members did not see the need to memorialize a month of service in a six year long war. Though the unit today does not claim to have served in a combat role, this month of service brought it very close. In thirty days, a unit that was organized to only serve the Governor and General Assembly marched over three hundred miles. For about two weeks, they were under arms and part of an American army that was actively monitoring British movements up and down the Hudson River. Had the British continued raiding after Kingston, they probably would have seen combat. Even if this does not constitute the official guidelines to earn them a battle honor, their service during the fall of 1777 deserves to be so much more than just a footnote in the history of Connecticut and its contributions during the Revolutionary War.

[1] Charles J. Hoadly, ed., The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, 15 vols. (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood, & Brainard Co., 1890), 13:544.

[2] History of the First Company Governor’s Foot Guard, Hartford, Connecticut, 1771-1901 (Hartford, CT: Danforth Press, 1902), 11. The event is still commemorated every September by members of the company. Each “Rochambeau Day” current members reenact the march in Hartford.

[3] Ibid, 10.

[4] John Roberts Pension Application, National Archives and Record Services, Washington D.C. In late 1776, Major Christopher French, who served in the British 22nd Regiment of Foot, was taken prisoner. He would be housed in the tavern belonging to William Knox and guarded/escorted by members of the Governor’s Foot Guard.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Charles J. Hoadly, ed., The Records of the State of Connecticut State Records, 4 vols. (Hartford, CT: Case, Lockwood, & Brainard Co., 1894-1942), 2:405.

[7] Ibid.; John Roberts Pension Application.

[8] Israel Putnam, General Orders Issued by Major-General Israel Putnam When In Command of the Highlands, In the Summer and Fall of 1777, Worthington C. Ford, ed. (Brooklyn, NY: Historical Printing Club, 1893), 82-83.

[9] Ibid, 83.

[10] Ibid, 84.

[11] George Clinton, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795—1801-1804. 2 vols. (New York: Wynkoop Hallenback Crawford Co., 1900), 2: 457-459, 460-461.

[12] Ibid, 460.

[13] Ibid. Putnam writes his letter from “Leroy Statsford,” which is today Staatsburg. He claimed that Wyllys’ Regiment was six miles ahead of his position, which is a close estimate to the distance between Staatsburg and Rhinebeck.

[14] John Roberts Pension Application.

[15] Brendan Morrissey, Saratoga 1777, Turning Point of a Revolution (Hailsham, UK: Osprey Publishing, Ltd., 2000), 86, 90.

[16] John Roberts Pension Application. Roberts, beginning in 1780, went on to serve on the three privateers before the war ended. Serving on the Active in 1781, he might have participated with its captain in the defense of New London when it was attacked that September by the British. However, he makes no mention of participation.

12 Comments

Thank you for the story of the Governor’s Foot Guard. I live in Avon, CT which is home to the Governor’s Horse Guard (it still participates in ceremonial events), and I knew very little about the Governor’s Guard and was not aware it had been involved in a military campaign. It might interest you to know that the Governor’s Horse Guard is still cherished ,and although it has shrunk in size, the citizens refuse to eliminate the budget for it ,and horse and riders( all volunteers) proudly marched in the last Veteran’s Day Parade in Hartford.

You’re welcome! Glad you enjoyed it Jane. I’m a former member of the 1st Company and remembering marching with the Horse Guard during the Veteran’s Day parade.

The research for this article came from an idea we had tossed around about recreating the march. Back then we believed it was only from Hartford to Rhinebeck. But the more I dug through primary sources, the more I realized the story might actually be a lot different.

I remember finding a document which stated the company was reimbursed by the Continental Congress for service at Peekskill, which right away contradicted the “official story.” Then I ran in Robert’s pension application by accident. He might be the only member that mentions his service in his application. I looked up several members and they were completely silent about the affair.

We owe Roberts a lot of credit, otherwise this cool little story would have been lost to history.

Matthew,

Question: if this is “the oldest, continuously serving military unit in the United States,” what does that do to the Massachusetts Independent Company of Cadets, founded 1741? See: http://www.history.army.mil/html/forcestruc/lineages/branches/mp/0211mpbn.htm

Was the Governor’s Foot Guard ever taken out of service and then reactivated?

Thanks, enjoyed your article.

Gary, I guess you could make the argument either way.

But unlike the Independent Company, the Governor’s Foot Guard has always kept its name and maintained a separate identity. It’s never been merged into the National Guard, but remains part of the active state militia. To the best of my knowledge, it has never been deactivated or reactivated, but has a continuous record of service since 1771.

I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

Thanks for the additional info., Matt.

Regarding uniforms, Fort Ticonderoga recently obtained an original one used by the Independent Corps of Cadets and which is interesting as it is “the oldest surviving America military coat”: http://www.fortticonderoga.org/blog/seeing-red/

Perhaps there is some kind of a fashion connection that can be inferred for the Governor’s Foot Guard.

Gary,

I was actually up at Fort Ticonderoga for the first time just a couple weeks ago. I did see the uniform of which you speak. It was pretty cool to see it in person!

As far as the Foot Guard uniform. The only reliable period description I know of is in Major Christopher French’s journal. When he was captured, French was guarded by the Foot Guard and he left a description of their uniform. I haven’t been able to get a copy so I haven’t seen the full description. From what I remember he said it was red with black facings. So there might be a connection. Their grenadier cap was also modeled after the British Warrant of 1768.

I’ve seen some far fetched undocumented sources saying the uniform they currently wear was modeled after ones captured from Major Acland’s grenadiers at Saratoga. I don’t have much faith in that one at all.

Matt

Matt,

I actually have images of French’s journal as transcribed and reported by the Connecticut Historical Society in 1990, which was kindly loaned to me by Don Hagist in preparing a prior article on French’s role as a prisoner of war (https://allthingsliberty.com/2015/05/major-christopher-french-prisoner-of-war/)

The journal runs about 110 pages and I briefly took a look at it, but, not to say it is not there, did not see any descriptions of his guards’ uniforms. However, if it was the Governor’s Foot Guard watching over him, it is clear that French and his fellow prisoners made their lives a living hell in the Hartford gaol!

I have a particular interest in the Independent Company of Cadets (whose lineage actually extends back to 1634 when it was known as the Boston Cadets) as they constituted the only trustworthy body of men that Governor Bowdoin could rely on at the time of Shays’s Rebellion. They were essentially his personal bodyguard, described as “men of good standing and influence in the community, high-spirited and manly and quick to resent an affront.” I do not know what kind of uniform they had, but in 1854 it was reported that up to that time it was white and trimmed in red. Bowdoin also commissioned another group of volunteers in Boston at the time called the “Republican Volunteers.”

As I describe in my book, Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786-1787, Bowdoin issued an arrest warrant for Shattuck (my half-uncle) in the early days of the “rebellion” and which was executed by the Independent Company along the snowy, icy banks of the Nashua River in November 1786. Unfortunately, they nearly severed his right leg when one of them (Lt. Fontesque Vernon was his name) struck out with a saber during the arrest. It was this shedding of blood that radically transitioned the, comparatively speaking, peaceful protests by farmers into the bloody confrontation that Shays had with militia troops at Springfield in January 1787, and which resulted in four deaths.

I don’t sense that these kinds of organizations had much high regard within the organized military establishment, but were mainly tolerated as a way to allow the well-to-do “dandys” to contribute to the effort without having to sign on for extended periods of time.

That’s really disappointing! I remember reading a brief contemporary description somewhere of them having a red uniform with black facings. Thought it was in French’s journal, but I guess not. Makes me really wonder where I saw it and why I didn’t write it down.

In one of the unit histories, it does claims that the uniform was based off of one captured from a grenadier at Saratoga. I suppose its possible, but with no citation you can check to reliably of the source.

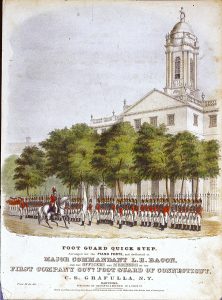

I very much enjoyed this article! As a musician, I was drawn to the 1845 illustration of the Foot Guard, which appears to include some members of the Guard who are playing instruments on the far left of the print. It’s interesting that no drum is shown in the band. I’m also curious about the citation for the print, which credits the “Hartford Courant,” a newspaper.

The print is obviously a piece of sheet music (not from a newspaper), and bears the title “Foot Guard Quick Step.” A ‘quick step’ was a type of march that later became a popular dance. It would have been performed prior to this publication by bands and/or orchestras, as this piece of sheet music is “arranged for piano.” That it is a separately published piece of music is also confirmed by the fact that it is offered for sale (Price .30? cts net), and states on the cover that it is published by Danforth & Brewer, No. 6 State Street, in Hartford.

I found a better copy of the music at the “Levy Sheet Music Collection,” which can easily be found with an online search.

Hi James, glad you enjoyed the article! You are correct the image is from sheet music. When I submitted images for the article, there were three of them, the editors obviously chose this one because it was definitely the better of the three and the only one to show the company in formation. The company did not have a band until the early 1800’s. Historians disagree as to what their Revolutionary War-era uniforms looked like and this shows them, in 1845, dressed in what is considered their traditional ceremonial uniforms. The one they wear today is just like the one pictured.

The reason it was credited to the Hartford Courant was that the image was obtained through Courant website. They used the same image for an article they wrote about the unit’s 200th anniversary.

I dug a little deeper after reading your comment and it looks like the Courant got the image from the Connecticut Historical Society, so it really should be credited to them. I’ve written to the editors suggesting they change the credit caption.

I would like to echo everyone’s comments on a job well done Matt! You did a fantastic job with this and I wish we had the opportunity to re-enact that march to New York!

Great article Matt. I just saw this article today, one of my friend sent it to me.

I was able to visit Newport, RI, and stop by Trinity Church to pay my respect to Admiral C. de Ternay (I know his family well enough…:)…) and I live in New York so I’m not that far away.

I have great interest for history and as you can imagine, the US war of independence as always interested me.