When a party is formed within the State which ceases to obey the sovereign and is strong enough to make a stand against him, or when a Republic is divided into two opposite factions, and both sides take up arms, there exists a civil war.

… it is perfectly clear that the established laws of war, those principles of humanity, forbearance, truthfulness, and honor … should be observed on both sides in a civil war.

Emer de Vattel, The Law of Nations, 1758[1]

One of the prickly issues facing George Washington as his army waited outside Boston in the summer of 1775 concerned prisoners taken by both American and British forces. As the leader of a rebelling faction, this was entirely unfamiliar territory to him; the treatment of captured British soldiers presented a distinct conundrum. The era’s rules of war most clearly applied to warring nations, whereas a civil war, as de Vattel’s highly regarded treatise Law of Nations defined, seemed to require something different, apropos employing equitable attributes of “humanity, forbearance, truthfulness, and honor.” Erring on the side of leniency and compassion was Washington’s inclination, but when faced with the countering positon of British General Thomas Gage, it was not so easy.

To the British commander there were no such delicate issues for this was an outright, unwarranted affront to established law, one that needed to be crushed before it spread. Coddling captured rebels hardly merited much concern; to Gage, the availability of the more draconian sanctions de Vattel described appeared most prominent in his mind.[2] It was a position that became all too real as the war unfolded and some 8,500 American soldiers died while in custody, hidden away in whatever ramshackle facilities might be available, including “local jails, barracks, warehouses, churches, underground mines, ships.”[3]

The two men’s positions become clear through an exchange taking place that August. After learning of conditions that captured American officers experienced in Boston, Washington angrily wrote to Gage of their having “been thrown indiscriminately into a common gaol appropriated for felons; that no consideration has been had for those of the most respectable rank, when languishing with wounds and sickness; that some have been even amputated in this unworthy fashion.”[4] He reminded Gage of his responsibility for their care, instructing that “the obligations arising from the rights of humanity and claims of rank, are universally binding and extensive.” Washington concluded with a stern warning:

My duty now makes it necessary to apprize you, that, for the future I shall regulate my conduct towards those gentlemen, who are or may be in our possession, exactly by the rule which you shall observe towards those of ours who may be in your custody. If severity and hardship mark the line of your conduct (painful as it may be to me) your prisoners will feel its effects; but if kindness and humanity are shown to ours, I shall with pleasure consider those in our hands only as unfortunate, and they shall receive the treatment to which the unfortunate are ever entitled.

Responding two days later, condescendingly refusing to acknowledge the rebel leader’s rank by addressing him as “George Washington, Esq.,” Gage opened with “To the glory of civilized nations, humanity and war have been compatible, and compassion to the subdued is become almost a general system.”[5] While this conciliatory language appears in agreement with Washington’s position, he continued, “your prisoners, whose lives, by the law of the land, are destined to the cord [emphasis in original], have hitherto been treated with care and kindness, and more comfortably lodged, than the king’s troops in the hospitals; indiscriminately it is true, for I acknowledge no rank that is not derived from the king.”

Gage then took Washington to task for his own treatment of British prisoners: “My intelligence from your army would justify severe recrimination. I understand there are of the king’s faithful subjects, taken some time since by the rebels, labouring, like negro slaves, to gain their daily subsistence, or reduced to the wretched alternative to perish by famine, or take arms against their king and country.” After expressing hope that Washington would similarly treat his prisoners with “sentiments of liberality” he ended by referring to the war’s illegality, while also expressing confidence in his own men’s loyalty and integrity: “I trust, that British soldiers, asserting the rights of the state, the laws of the land, the being of the constitution, will meet all events with becoming fortitude. They will court victory with the spirit their cause inspires, and from the same motive will find the patience of martyrs under misfortunes.” Clearly, on the issue of prisoners Gage had assumed an unquestioned position on the side of law and order portending little regard for compassion.

Piqued at Gage’s refusal to at least recognize the prerogative of rank that allowed officers and common soldiers to live separate from one another, Washington immediately retaliated against those under his control. “Very contrary to his disposition,” according to his secretary Joseph Reed in writing to the Massachusetts Council, Washington ordered that British officers held in Watertown and Cape Ann receive the same treatment as American prisoners, directing their confinement in Northampton jail to live alongside those of lower rank. Reed does not explain why, but the following day Washington relented with regard to one favored group of prisoners who had “committed no hostilities against the people of this country” and directed they be allowed parole to travel within a specified distance from where they were detained.[6]

Washington was already communicating with various provincial committees concerning the confinement of enemy soldiers and arrangements were in place to house those of less importance in jails in Ipswich and Taunton, while others of more renown were taken to Northampton. Notwithstanding, Reed made clear in his directions that it was Washington’s wish they carefully handle them “such as to compel their grateful acknowledgement that Americans are equally merciful as brave.”

As Washington wove this difficult course in assigning appropriate conditions of confinement commiserate with the degree of danger a particular prisoner posed, he responded to Gage’s latest missive in equally condescending tone. He told Gage that he had investigated allegations of mistreatment of British prisoners and found them wholly unfounded. Then, after dismissing the remainder of his complaints, he ended on a dire note: “I shall now, Sir, close my correspondence with you, perhaps forever. If your officers who are our prisoners receive a treatment from me, different from what I wished to shew them, they, & you will remember the occasion of it.”[7]

Washington didn’t know that just as he was threatening retaliation a situation dropped squarely into his lap testing his resolve. As he waited for Gage’s reply to his first letter, the supply ship Hope out of Cork, Ireland, was making its way up the Delaware River, ignorant that the colonies were in full rebellion. The Pennsylvania Committee of Safety ordered the vessel seized, discovering clothing for two regiments destined for Gage’s army onboard accompanied by five British soldiers enroute to Boston: Irishman Major Christopher French, 22nd Regiment of Foot, Ensign John Rotton, 47th Regiment, volunteer Terrence McDermot, and two private soldiers acting as their servants. The committee ordered these men detained and brought before them on August 16.[8]

Before their appearance before the committee, French, as senior officer speaking on the behalf of the others, lodged a protest. He argued that they had arrived in America not under arms and without knowing hostilities had broken out, therefore they could not be considered prisoners of war. This contention was rejected out of hand. Described the following year as “about fifty years of age, wears his hair, is small of stature, hard favored,” the obstinate French was no stranger to North America or to the laws applicable to prisoners of war as described by de Vattel.[9] He had entered the army in 1744 as ensign with the 22nd and by the end of 1756 was a captain commanding a company during the French and Indian War. Most recently, while in England in June 1775, he was promoted to major and ordered to join his regiment, only to be interrupted in the effort by Pennsylvania authorities.[10]

French, Rotton and McDermot were brought before the committee which quickly concluded they had “designedly came hither with an intention of joining the ministerial army at Boston, under the Command of General Gage, who is now acting in a hostile & cruel manner against his majesty’s American subjects.”[11] Deciding that Washington was the appropriate official to decide the fate of these early prisoners of war led by an officer of unwavering loyalty and resolve, and to prevent their “becoming additional instruments of oppression,” the committee granted them parole to travel to Cambridge. French, however, first extracted a document from the committee attesting that he claimed he was not a prisoner of war because of the circumstances he found himself in when taken. He was also successful in obtaining the return of their baggage, but unsurprisingly he failed to obtain the clothing destined for the British army. The committee then arranged for two gentlemen to accompany the parolees on their trip.

first one on August 15, 1776 (George Washington Papers, Library of Congress).

As they awaited their departure, French wrote directly to Washington on August 15, also refusing to address him by rank as Gage had done, simply calling him “Sir.” He requested that Washington forward two letters, to Gage and another officer, explaining why they had been unable to join them. When Washington received his letter the situation in Cambridge was one of great confusion and hardly an environment conducive to watching over prisoners. He wrote to the Pennsylvania committee directing that they be taken to Hartford and placed under the supervision of the local committee, while also responding directly to French that he had forwarded his letters and of the change in plans, of which he had “no doubt of your acquiescence.”[12]

French received Washington’s letter on September 3 just as he reached Framingham, only twenty miles short of his destination. Clearly frustrated at being prohibited from continuing, French responded in a most dictatorial and legalistic fashion, lecturing Washington on his obligations:

I consented [to signing my parole] rather than accept the alternative of remaining prisoner at Philadelphia; I must farther offer to your justice & knowledge of military rules that before I would sign to my parole … I objected to our being by any means considered as prisoners, first because we came to America unknowing of any hostilities having been commenced, secondly that in case we had arrived, having heard of it at sea, the custom of war allots a certain period for the departure of the ships & subjects of the inimicable nation; neither of these reasons however had sufficient weight with the committee.[13]

He then brazenly told Washington that because of his particular circumstances, he expected to be allowed to return to his regiment without an exchange of prisoners taking place.

As French wrote, Reed was doing likewise, advising the British officer that:

General Gage’s treatment of our officers, even of the most respectable rank, would justify a severe retaliation. They have perished in a common jail, under the hands of a wretch who had never before been employed but in the diseases of horses. General Washington’s disposition will not allow him to follow so unworthy an example. You and your companions will be treated with kindness, and upon renewing your parole at Hartford, you will have the same indulgence as other gentlemen under the like circumstances.[14]

However, after receiving French’s latest admonition that he expected to receive special treatment, Reed responded on Washington’s behalf in scathing fashion:

The General has directed me to acquaint you that on the fullest consideration he is of opinion that your detention is both justifiable & proper. While the appellation of Rebel [recently used by Gage] is supposed to sanctify every species of perfidy & cruelty towards the inhabitants of America, it would be a strange misapplication of military rules to enlarge such gentlemen as may think themselves bound by a mistaken notion of duty to become the instruments of our ruin.[15]

If things were rocky then, much more was in store for all parties.

At the time of their parole the British prisoners were allowed to retain their swords, a trifling indulgence of little importance that French never fully appreciated and which raised the next set of problems when he reached Hartford. As the local committee explained to Washington on September 18:

… he soon began to raise objections against conforming to the same regulations with the other officers, prisoners, here, insisted that there was an essential difference, he not being taken in arms, as he said, but this was not all, he gave out, in high tone, that had he joined his regiment he should act vigorously against the country, & do everything in his power to reduce it, in short, he talked in so high a strain that the people viewed him as a most determined foe; & in this light, they would not bare with his wearing arms at any rate.[16]

Of course, nothing was easy with French and that same day he dashed off another missive to the beleaguered Washington explaining his side of the story. The committee had acted most egregiously against them, he said, based upon complaints coming from the “lower class”:

… they put in a new [parole] clause to which they desired our acquiescence vizt: That we should not wear our swords. The day before their meeting (Monday) I had been informed that the lower class of townspeople took umbrage at our wearing them, and therefore represented to the sub-committee that we had been permitted at Philadelphia to wear them as soon as we had given our paroles, and that I supposed the permission general as well as our paroles, & both equally binding, & therefore requested we might not be insulted by being obliged to surrender them here, merely to gratify the populace; I also informed them it was customary for officers (& volunteers, being Gentlemen,) on their paroles to be allowed to wear their swords.[17]

Never missing an opportunity to argue a point, French then launched into a fine legal analysis concerning the authority of citizens over their committee and his faith that Washington, with his superior knowledge of the law, would make it all aright:

… however injurious we consider an act done by a convention of people not legally a court, since deficient in numbers to determine for, as well as against us till your pleasure is known, which from the stating of the matter in it’s real & true light, your long service & intimate acquaintance with military rules & customs, to which I once more appeal, I make no doubt will be in our favor….

Days later, a clearly exasperated Washington responded to both the Hartford Committee and French over what seemed such a trivial matter. He thanked the Committee for housing the prisoners, asking their further consideration in setting a good example because, “We know not what the chance of war may be—but let it be what it will the duties of humanity & kindness will demand from us such a treatment as we should expect from others the case being reversed.”[18] With French, it was another matter:

When I compare the treatment you have received with that which has been shown to those brave American officers who were taken fighting gallantly in defense of the liberties of their country, I cannot help expressing some surprise that you should thus earnestly contest points of mere punctilio. The appellation of Rebel has been deemed sufficient to sanctify every species of cruelty to them, while the ministerial officers, the voluntary instruments of an avaricious & vindictive ministry claim upon all occasion the benefit of those military rules which can only be binding where they are mutual. We have shown on our part the strongest disposition to observe them, during the present contest, but I should illy support my country’s honour and my own character if I did not shew a proper sense of their sufferings by making the condition of the ministerial officers in some degree dependent on theirs.[19]

He then told French that, “My disposition does not allow me to follow the unworthy example set me by General Gage to its fullest extent. You possess all the essential comforts of life, why would you press for indulgences of a ceremonious kind which give general offence?” Finally, he made a wise recommendation that,

You will easily conceive how much more grateful a compliance with the wishes of the people (among whom your residence may be longer than you expect) will appear when it is the result of your own prudence and good sense rather than a determination from me: I therefore should be unwilling to deprive you of an opportunity of cultivating their esteem by so small a concession as this must be.

Not one to let another have the last word, and perhaps recognizing the futility of continued insistence on the return of swords, French wrote again. This time he denied engaging in pettiness or his role as a “ministerial” officer, while also assuming an apologetic tone:

… would it not be the greatest meanness (not punctilio) in us to submit lamely, and without representing it? As I never held any commission from a minister I cannot conceive with what propriety you can call me a ministerial officer, You are pleased to observe I am an old officer, true Sir, I have served His Majesty, King George the third, and his royal grand-father near thirty three years, I flatter myself, with honor, I have always done it, & do so still from that motive, and shall at all times think I do right in obeying his ministers acting under his legislative power (as I am satisfied they now do) from constitutional principles.[20]

And, unsurprisingly, there was more as French requested Washington to allow his party to be relocated to Middletown where there was a congregation practicing the dictates of the Church of England.

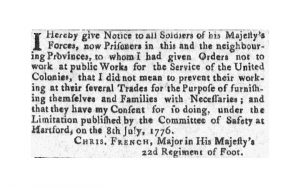

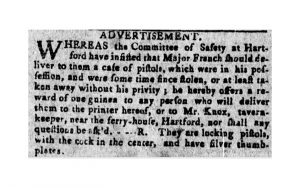

keeping track of it in captivity was difficult. He placed this ad in the

Connecticut Courant; it ran on August 19, 1776 and again the following week.

As these exchanges took place, Washington received a welcome visit of a three-man committee headed by Benjamin Franklin, ordered by the Continental Congress to address some of his most critical needs. While manning and supplying the army constituted much of the discussion, Washington’s list of twenty-nine questions included two dealing with prisoners. The British officer as his third concern: “Major French’s case about his Sword & dispute with the Committee of Hartford: something to be done in it;” while issue number twenty-two asked, “In what manner are Prisoners to be treated? What allowance made them and how are they to be cloathed?”[21] While nothing was decided with regard to French specifically, they resolved that others “be treated as Prisoners of War – same rations as soldiers & that officers may be furnished with cloathing upon their bills.”

Just before the committee arrived, Washington wrote to French that he planned to bring up the sword issue with them, warning that “My time & other engagements does not admit my continuing this correspondence.” However, after meeting with Franklin and learning that no arrangements had been made concerning the swords, Washington did write once again. This time he made clear that the swords would not be returned “as it gives such general dissatisfaction to the good people of the country” and that he had no objection to his being moved to accommodate his religious needs providing Connecticut governor Jonathan Trumbull agreed. He closed with yet another request that French not cause further problems, “I wish you all the happiness consistent with your situation & while the inhabitants of America treat you with humanity & kindness, I trust you will make a suitable return. It is not grateful to me to hear the respectable citizens of any town treated with incivility or contempt.”[22]

Two weeks later, French dashed off another missive taking Washington to task for his legal analysis concerning the swords, but also promising “I shall not give you any more trouble on this topic.”[23] Once again insisting on having the final word, the condescending officer also wrote that he was mystified over any allegation of his being rude to the population, “I have endeavored to find out in what instance I have treated the respectable citizens of any town with incivility or contempt, and affirm I cannot, upon the strictest revisal of my letters, observe the least trace of it, unless my calling Hartford a little paultry town can be so interpreted.”

The “paultry” town of Hartford had put up with much in providing housing for the many British soldiers allowed parole. The influx of unwanted visitors took up residency in houses and taverns, fully expecting the local population to provide them with food, clothing and money; French himself demanded that he and his fellow soldiers receive seventeen shillings six pence each day.[24] They also peppered the local committee with petitions to allow them to travel farther than their paroles allowed.

In fact, French had larger designs that included receiving permission to return home to Ireland. He wrote to Horatio Gates with so many requests that in February Washington’s headquarters responded, denying the request and asking him to consider the treatment afforded the captured Ethan Allen:

I am also commanded to tell you that the General is surprised a Gentleman of Major French’s good sense & knowledge should make such a request—Let him compare his situation with that of such Gentlemen of ours who by the fortune of war have fallen into the hands of their enemy—what has been their treatment? Thrown into a loathsome prison and afterwards sent in irons to England. I repeat—Let the Major compare his treatment with theirs & then say whether he has cause to repine at his fate.[25]

Tensions in Hartford were mounting at that time as word of the defeat at Quebec on December 31 arrived. With an enraged population surrounding them, French and his men were subjected to threats as bands of men sought to harm them. While avoiding injury, they remained under close scrutiny in the next months as allegations of involvement with Loyalists, spying, and possession of firearms were hurled at them. French brought himself into further disrepute for defensing of one of his men suspected of speaking disrespectfully of the Continental Congress, engaging General Charles Lee in a spirited discussion in defense of Parliament, and for reportedly seeking ways for British prisoners to cause mayhem among the populace.[26]

Conditions persisted and on March 21, 1776, French and nine others decided it was time to involve the Continental Congress. They explained to Congress, in their petition seeking removal to another location and additional clothing, that

It is their earnest wish and design to avoid giving any just and reasonable cause of offense to the inhabitants in their neighborhood, yet the most trivial incidents are industriously misrepresented and maliciously propagated through the country, insomuch that their personal safety is actually endangered by mobs, there being none of the Continental troops here to grant them a safeguard.[27]

Unwilling to put up with further abuse, one of the men escaped shortly thereafter, only to be captured and, “after having tied him, knocked him down, & beat & abused him in the grossest manner,” thrown into the local jail.[28]

The challenges posed by the Hartford detainees were hardly unique, being experienced in other locales as well. Congress finally enacted regulations dealing with them. These included, in part, that: persons taken in arms on board any prize or in the land service be deemed prisoners of war and treated “with humanity;” officers not be permitted to live in or near any seaport town or public post-road; officers and privates “be not suffered to reside in the same places;” officers be allowed two dollars a week for subsistence, to be repaid when released from captivity; officers allowed freedom on parole or, if they refused, to be jailed; and local committees of inspection and observation be authorized to supervise and coordinate among themselves everything pertaining to prisoners of war.[29]

With their authority now unquestioned, the Hartford committee imposed additional requirements on the detainees, prohibiting their being out after dark. French was himself accused of intending “to head a party of Tories and cut all their throats,” leading to searches of the prisoners’ quarters for weapons. When Springfield and Westfield authorities actually seized weapons from prisoners, additional rules were imposed not allowing them to leave town or place of work without a permit, and restricting their access to spirituous liquors.[30]

Conditions had now reached such a level that French decided it was time to present Washington with his latest demand. It had been almost a year since he and his fellows were detained and on July 22 he wrote that it was his understanding when they signed their paroles it was for a twelve-month period. With that time about to expire he wanted Washington to “give orders,” presumably a renegotiation of the terms of his parole.[31] Washington surely must have chuckled at such a notion, sending a copy of the demand to John Hancock at the Continental Congress and writing to the Hartford committee:

This conduct I must confess appears very extraordinary as he cannot be ignorant that he has been hitherto considered as a prisoner of war, and that accepting his parole at first was an indulgence granted, solely to make his situation more easy & comfortable, & to prevent his experiencing the disagreeable effects of a close confinement.[32]

But he saved his most damaging assessment for French himself, telling him that he consulted with those of “knowledge and experience” and none could agree he was entitled to relief. Even if he was inclined to help out, Washington advised it was “not in my power, even if your general line of conduct as a prisoner had been unexceptional.” Then, after mentioning the possibility of an exchange of prisoners in the future, he closed, “it will then be a pleasing part of my duty to facilitate your return to your friends and connections, as, I assure you, it is now a painful one to disappoint you in an expectation which you seem to have formed in a full persuasion of being right and in [which] on mature deliberation, I am so unhappy as totally to differ from you.”[33]

The following day, perhaps recognizing the stinging effect of his words, Washington wrote once again, this time reassuring French “that both duty & inclination lead me to relieve the unfortunate & that I agree with you, that your long & early captivity gives you a very just claim to special notice, & I shall be happy in furthering your wishes as far as my station will admit.”[34]

As he fought for his freedom, French ran afoul of the local committee when he issued orders to a fellow parolee, Fort Ticonderoga’s former commander Captain William Delaplace, to not attend services at a church where the rebel cause was receiving favorable reviews. While Delaplace initially resisted, he eventually obeyed, but not before the committee found out and brought French up on a charge of interfering with their authority over prisoner affairs. When ordered to sign a new parole, French refused and was immediately put into jail, guarded at times by a young man patrolling outside. British successes on Long Island filtered in and the two conversed about the situation, with the youth telling French that if the British made it to Hartford the prisoners would not live to see it. When French asked why, the boy told him “he was ‘sartin sure’ the people would put us all to death, as he had heard some of them declare they would.”[35]

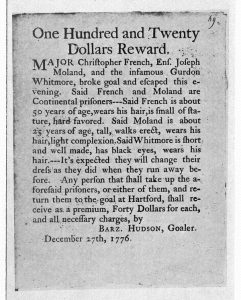

With pressure increasing, on September 10 two prisoners escaped, leaving French behind to experience yet increased surveillance day and night. Then, after two months of planning, on November 16 he and four others departed, only to be quickly recaptured.[36] Undeterred, on December 27, success was finally achieved when French and two others managed to escape once again and evade their pursuers. Upon his return to British lines, French remained in America, serving briefly with the Queen’s Rangers before rejoining the 22nd Regiment, then the 52nd, before retiring homeward in 1778.[37]

Major Christopher French represented a unique challenge for both Washington and the Continental Congress as they faced one of the more difficult problems presented by warring factions. There were no binding rules of conduct; only those traditionally accorded combatants in the past and concepts of honor, chivalry, and respect stood in their place. As Washington and Gage bespoke their own perceived notions of what all of this meant, while also struggling to understand how positions of societal and military rank affected each consideration, officer and soldier prisoners alike suffered. Allowing paroles was certainly the least restrictive method in their control when wholesale incarceration was out of the question, but it then placed undue pressures on communities, and their various committees, to see the paroles honored. The British had no such luxury, working in a distant land with little ability or available resources to devote to the niceties that might otherwise be allowed the jailed. So, as horrendous as the conditions were for American prisoners, they simply reflected a want of capacity that resulted in so many of their deaths. Whereas the British also employed a degree of harshness in the face of these stark realities, Washington and the Congress could afford to exercise a more tolerant point of view and, to their credit, give full weight to “those principles of humanity, forbearance, truthfulness, and honor” that de Vattel described in his Law of Nations.

I am most grateful for the enthusiastic assistance of Don N. Hagist in the preparation of this article. Don is avid student of Christopher French and graciously loaned me his copy of the Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin described below and which contains French’s journal.

Unfortunately, article length does not allow for a full recitation of French’s entries, but for anyone inclined to seek it out, it is a wonderful account of the travails of an intelligent, educated, legally-inclined, protective, and persistent British officer attempting to single-handedly uphold England’s honor under difficult circumstances. Suffice it to say, French in no way, at any time, ever bent to the will of his captors and consistently exhibited a disdain for any attempt to do so.

[1] Emer de Vattel, The Law of Nations or the Principles of Natural Law Applied to the Conduct and to the Affairs of Nations and of Sovereigns, translation of the 1758 edition (Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1916), 338; see also, Hugo Grotius’s 1625 work, The Rights of War and Peace (London: B. Boothroyd, 1814). While de Vattel provides no definition of a revolution per se, he does state that “the term rebellion is only applied to an uprising against lawful authority, which is lacking in any semblance of justice.” Since the British and Americans interpreted their respective positions in opposing ways, de Vattel’s description of a civil war as the equivalent of two nations at odds, and obligated to conduct themselves in accord with the rules stated, is adopted for this article.

[2] For example, refusing to give quarter, confining, fettering, refusing to feed when lacking resources, execution if security is threatened, enforced slavery, demanding ransom, and taking family members prisoner.

[3] Charles Royster, A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army & American Character, 1775-1783 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979), 378; Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, The Spirit of Seventy-Six (New York: HarperCollins Publisher, Inc., 1958), 845.

[4] George Washington to Thomas Gage, August 11, 1775, American Archives, Series 4, vol. 3:245.

[5] Gage to Washington, August 13, 1775, The London Magazine or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer for the Year 1775 (London: By His Majesty’s Authority, 1775), 44:519-520.

[6] Joseph Reed to James Otis, August 14, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0227), FN 1. This group of prisoners was the captain and crew of a British surveying expedition working along the Maine coast in July 1775; when they put into Machias harbor without knowledge that hostilities had already broken out they were immediately taken into custody.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The uniforms were for the 22nd and 40th Regiments, which had landed in Boston in June. Some accounts misstate the quantity of clothing, giving figures up to 7500 uniforms; a detailed inventory was taken, however, and indicates about 750 uniforms. Inventory of sundry clothing received at Cambridge, George Washington Papers, Series 4 Reel 33, Library of Congress.

[9] Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania from the Organization to the Termination of the Proprietary Government (Harrisburg: Theo. Fenn & Co., 1852), 303; “Advertisement for Apprehension of Major French and Others,” December 27, 1776, American Archives, Series V, 3:1255.

[10] E. Alfred Jones, “A Letter Regarding the Queen’s Rangers,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (Richmond, VA: 1922), 30:371.

[11] Minutes of the Provincial Council of Pennsylvania, 302.

[12] Washington to Christopher French, August 31, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0284).

[13] French to Washington, September 3, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-01-02-0301).

[14] Ibid., FN 1.

[15] Ibid., FN 3.

[16] Thomas Seymour to Washington, September 18, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0014).

[17] French to Washington, September 18, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0009).

[18] Washington to the Hartford Committee of Safety, September 26, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0045).

[19] Washington to French, September 26, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0043).

[20] French to Washington, October 9, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0119).

[21] Questions for the Committee, October 18, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0175-0002).

[22] Washington to French, October 25, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0216).

[23] French to Washington, November 13, 1775, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0335).

[24] Herbert H. White, “British Prisoners of War in Hartford during the Revolution,” Papers of the New Haven Colony Historical Society (New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1914), 8:259.

[25] “Charles Lee to Washington, January 15, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-03-02-0066), FN 1.

[26] White, “British Prisoners of War in Hartford,” 266-268.

[27] Memorial from the British Prisoners at Hartford to the Continental Congress, American Archives, Series 4, Vol. 5:452-453.

[28] Major French’s journal, 22 May 1776, in Sheldon S. Cohen, “The Connecticut Captivity of Major Christopher French,” The Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin 55, nos. 3-4 (Summer/Fall 1990): 147.

[29] Journals of the American Congress, 1774 to 1788 (Washington, DC: Way and Gideon, 1823), 1:349-351.

[30] White, “British Prisoners of War in Hartford,” 269-270.

[31] French to Washington, July 22, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0312).

[32] Washington to the Hartford Committee of Safety, August 7, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0454).

[33] Washington to French, August 7, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0450).

[34] Washington to French, August 8, 1776, Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0466).

[35] White, “British Prisoners of War in Hartford,” 272-273.

[36] Ibid., 274.

[37] Jones, “A Letter Regarding the Queen’s Rangers,” 370.

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"James Lafayette (James Armistead),..."

Hi Ken, Thank you for this article! I thought you might like...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...