On June 20, 1775, Patriots of the Cumberland Association met at Liberty Point, the space currently located between the intersection of Bow Street and Person Street in what is now Fayetteville, North Carolina.[1] At the time, Cumberland County, which included the present-day counties of Moore, Hoke and Harnett, was inhabited by a large concentration of Scottish Highlanders, most of whom were loyal to the British government. Yet on this date, Cumberland Patriots took a stand for independence. A table was brought from Barge’s Tavern, and fifty-five men, led by Robert Rowan, signed the Cumberland Association, a document declaring a willingness to defend their rights against the abuses of the British government.[2]

The Cumberland Association said the following:

At a general meeting of the several committees of the district of Wilmington, held at the court-house in Wilmington, Tuesday, the 20th June, 1775;

Resolved, that the following association stand as the association of this committee, and that it be recommended to the inhabitants of this District to sign the same as speedily as possible.

The actual commencement of hostilities against this continent by the British troops in the bloody scene on the 19th of April last near Boston—The increase of arbitrary impositions, from a wicked and despotic ministry, and the dread of instigated insurrections in the colonies, are causes sufficient to drive an oppressed people to the use of arms:

We therefore the subscribers of Cumberland County, holding ourselves bound by that most sacred of all obligations, the duty of good citizens towards an injured country, and thoroughly convinced that under our distressed circumstances we shall be justified before God & man in resisting force by force; Do unite ourselves under every tie of religion and honour, and associate as a band in her defence against every foe, hereby solemnly engaging that whenever our continental or Provincial Councils shall decree it necessary, we will go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety: This obligation to continue in full force until a reconciliation shall take place between Great Britain and America, upon constitutional principles: an event we most ardently desire; and we will hold all those persons inimical to the liberty of the colonies, who shall refuse to subscribe this association; and we will in all things follow the advice of our General Committee, respecting the purposes aforesaid, the preservation of peace and good order, and the safety of individual and private property.[3]

The men who signed came from diverse backgrounds: Robert Rowan was a former Cumberland County Sheriff and current magistrate, others such as Lewis Barge and James Gee were hatters, many of them owned taverns, and Thomas Cabeen was a tanner.[4] Their signing indicated a willingness to risk their lives in the Patriot cause.

The Cumberland Association document was very similar to Wilmington-New Hanover’s Association’s statement signed the previous day.[5] New Hanover’s had not been a surprise, as Wilmington was a hotbed of Patriot sentiment.[6] Unlike New Hanover, Cumberland County had a very strong Loyalist presence. At the time, most of Cumberland County seemed sympathetic for the Crown; even those chosen as members of the Provincial Congress would later support the British at Moore’s Creek.[7] Cumberland, along with Anson and nearby Bladen counties, “led all the others in the number who fought in both the loyalist militia and the regularly enrolled Loyalist regiments.”[8] Historian Robert DeMond even estimated that as much as two-thirds of Cumberland County were Loyalists, drawing on a letter from Col. David Smith to Gov. Richard Caswell in July 1777, where he said that it was “evident that two-thirds of Cumberland county intend leaving this State and are already become insolvent,” as residents had refused to take oaths to the Revolutionary government.[9] Historian William Henry Foote noted that before 1776, “the majority of the inhabitants of what was Cumberland were in favor of the crown, and even disposed to assist Governor Martin.”[10] The strength of the Loyalists movement in Cumberland makes it all the more notable that a group of fifty-five men banded together and created the Cumberland Association.

The movement towards the Cumberland Association had begun back in 1774, in response to the Intolerable Acts and the closure of the Port of Boston. This had led to the First Continental Congress that fall in Philadelphia. The Continental Congress resolved to enter a nonimportation, nonconsumption and nonexportation agreement, known as the Articles of Association, in October.[11]

The Articles of Association were scheduled to go into effect in December and called for committees to be chosen in every city, county and town to enforce the Association. Committees of Safety soon formed to enforce the Continental Congress’s mandates.[12] By November, the Wilmington Safety committee formed to “carry more effectually into Execution the resolves of the late congress held at Philadelphia.”[13] By the end of 1774, North Carolina had eighteen counties and four towns with safety committees, and Wilmington’s was perhaps the most active, led by Cornelius Harnett, the “Samuel Adams of North Carolina.”[14] By January 4, 1775, the Wilmington and New Hanover committees combined.[15] Other committees formed in North Carolina, including in counties such as Rowan, Mecklenburg, Tryon and Pitt.[16]

Cumberland was part of the New Hanover region and Wilmington District.[17] Cumberland County had its own committee of safety, though original committee minute records have to date not been found.[18] The safety committees would enforce the resolves passed by the Continental and Provisional Congresses.

By April 1775, Royal Governor Josiah Martin had called the General Assembly, but at the same time, Patriots had assembled the Second Provincial Congress, which then promptly endorsed the Continental Association that the Continental Congress had published the previous fall, and said that the measures taken by the committees in the colony’s towns and counties were such that “they were compelled to take for that salutary purpose.”[19]

Shortly afterwards, Governor Martin dissolved the assembly. Martin declared on April 8 that the assembly was dissolved because it was now “incompatible with the Honour of the Crown and the safety of the people” along with subverting “the Constitution.”[20] By May, news of the Battle of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts had reached North Carolina.[21] This kicked the North Carolina committees of safety into action.

On May 20, following the dissolving of the General Assembly by Governor Martin, the Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee “Resolved that the Committees of the Respective Counties in this District be Invited to meet in Wilmington on the 20th of June next in order to deliberate on several matters of Importance that will be laid before them respecting the General Cause of America.”[22]

Soon after this, the Mecklenburg Safety Committee published their Mecklenburg Resolves on May 31.[23] Then in early June the Safety Committee of Rowan County resolved “that by the Constitution of our Government we are a free People, not subject to be taxed by any power but that of that happy Constitution.”[24]

By this time, Governor Martin was threatening to use force to resist all “Promoters of Sedition, and Disturbers of the Peace,” so this “pushed the combined safety committees from the town of Wilmington, as well as New Hanover, Brunswick, Bladen, Duplin, and Onslow Counties, to issue a new “Association” that had to be signed by all inhabitants of the Lower Cape Fear.[25] This association committed its signatories to resist “force with force” and sacrifice their lives for the Continental or Provincial Congresses.[26] On June 19, Monday, The Wilmington-New Hanover Association signed the Association of the Committee and “Recommended to the Inhabitants of this District to sign the Same as speedily as possible.”[27] The next day, Cumberland Patriots signed their association.

The associations were a test, used to force residents to publicly “declare their sentiments” to the Patriot cause.[28] Cumberland’s committee had members who had visited the Wilmington committee, and they were part of Wilmington’s district, making their Association a way of signing on to the Wilmington-New Hanover Association. By August, other committees made statements advocating for defense of their liberties, such as the Tryon County Committee’s Resolves, which resolved to obey the King, but only if he “secures to us those Rights and Liberties which the principles of Our Constitution require.”[29] The Cumberland Association fit neatly into the growing independence movement in America.

Cumberland’s Association was similar to the other published associations in North Carolina. In terms of language, it is almost identical to the first paragraph of the Wilmington-New Hanover Association, with only “Cumberland” in place of “New Hanover” and “General Committee” instead of “our Committee.” However, the Wilmington Association then goes on for another couple of pages, listing separate resolves regarding Governor Martin’s June 16 proclamation, while Cumberland’s stops after the one paragraph.[30] The language of the document is also similar to the Tryon Resolves of August, with both commenting on the actions of the British troops at Lexington and Concord and declaring the right to defend themselves and their rights against British violations.[31]

While the associations were very similar, the county of Cumberland was unique compared to the other counties that made associations in the spring and summer of 1775. Out of all the North Carolina counties that signed associations, Cumberland had the most active Loyalist population, shown through Loyalist claims made after the Revolutionary War (see Table 1). While this does not prove that the Loyalist movement was stronger in Cumberland than elsewhere (claims could be lost, and dead Loyalists did not always have associates who could make claims for their families), Cumberland had more Loyalists make claims after the war than all the other association counties combined, which indicates that the Loyalist movement was much stronger in Cumberland than the other counties. Two of the Cumberland’s signers themselves—Maurice Nowland and Aaron Vardy—later came out as Loyalists and were captured at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge.[32]

Table 1: Loyalist Claims by Association County[33]

| County | Loyalist Claim Filed |

| Mecklenburg | 1 |

| Rowan | 6 |

| New Hanover[34] | 27 |

| Cumberland[35] | 50 |

| Tryon | 3 |

| Pitt | 0 |

Cumberland was also the only county in the state which had Loyalists captured at Moore’s Creek who had previously been members of the Provincial Congress: Farquard Campbell, Thomas Rutherford, Alexander McKay and James Hepburn.[36] These Loyalists were elite men in Cumberland society: Farquard had served as a magistrate for at least eight years since 1761 and had served in the General Assembly before serving in the Provincial Congress.[37] James Hepburn had been a Cumberland County magistrate in 1774, and Thomas Rutherford served in both the General Assembly and had been head of the Cumberland County militia, and had previously served as a deputy secretary to Colonial Governor William Tryon.[38] The background and sheer number of Loyalists in Cumberland County makes the Cumberland Association stand out, since it was written in a county that was lukewarm at best towards Revolution.

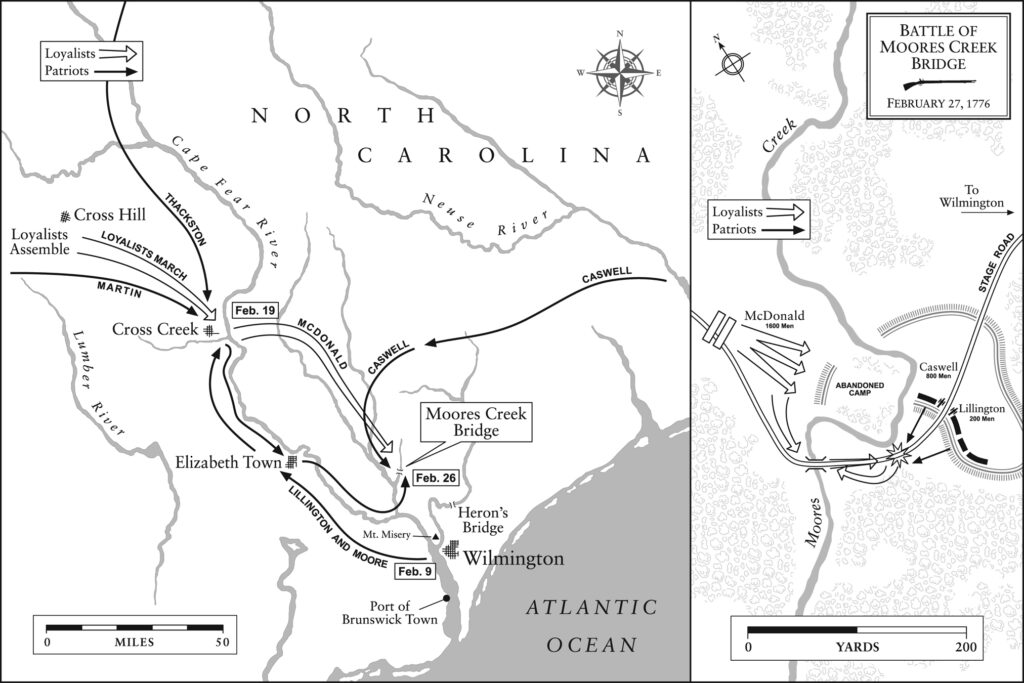

During the war that followed, many signers of the Cumberland Association suffered violence and great risk to their lives at the hands of local Loyalists. Before the Battle of Moore’s Creek in February 1776, Cross Creek was used as a staging ground for the Loyalist forces, with Rutherford calling on Loyalists to rally to the King’s Standard at Cross Creek.[39] When the Loyalists then gathered in Cross Creek, they confiscated the gunpowder that the Cumberland County Committee of Safety had been storing for Patriot use, maintaining control of the region.[40] Many Loyalists from the county then joined the march to Wilmington. Later in February, after the Battle of Moore‘s Creek, twenty-one Loyalists from Cumberland were taken prisoner.[41]

During the war that followed, many signers of the Cumberland Association suffered violence and great risk to their lives at the hands of local Loyalists. Before the Battle of Moore’s Creek in February 1776, Cross Creek was used as a staging ground for the Loyalist forces, with Rutherford calling on Loyalists to rally to the King’s Standard at Cross Creek.[39] When the Loyalists then gathered in Cross Creek, they confiscated the gunpowder that the Cumberland County Committee of Safety had been storing for Patriot use, maintaining control of the region.[40] Many Loyalists from the county then joined the march to Wilmington. Later in February, after the Battle of Moore‘s Creek, twenty-one Loyalists from Cumberland were taken prisoner.[41]

After the Patriot victory at Moore’s Creek, the Loyalist movement in the region died down for a while, before coming back with a vengeance in 1780-81, during the Tory Wars. Signers Robert Rowan and Theopolius Evans were captured by Tories around this time and had to escape up a chimney to avoid being hung.[42] Rowan’s wife, Susannah, was then threatened after his escape, and barely escaped with her life.[43] In the summer of 1781, a Tory raid of Cross Creek, led by Col. Hector McNeil on August 14, 1781 resulted in the capture of numerous government officials, including Robert Rowan. Fellow signer Col. James Emmett hid out in the swamp to avoid capture but was captured anyway when he tried later to exit the swamp.[44]

Even those who did not actively fight had to endure hardship and deprivation during the struggle. Signer Lewis Bowell suffered considerable damage to his bakery when the British came through in the spring of 1781 and was afraid for his life.[45] Signer James Gee’s wife, Mary, had to trick Loyalist soldiers who had captured signers Theophilus Evans and John Oveler one night. She managed to get the Loyalist soldiers so drunk that she was able to sneak out and cut the prisoners free, though her life, as well as that of the signers, was in danger.[46] All told, there were at least twelve signers and wives who had dangerous run-ins with Loyalists during the war over ten recorded instances during the conflict.[47] During the Tory War, the violence was such that the Cumberland area has even been said to have been the scene “of perhaps the most sustained internecine warfare in the entire Revolution.”[48]

Despite this personal risk, many signers boldly took on roles in leading the Patriot forces in Cumberland County. Robert Rowan served in the 1st North Carolina Regiment in the North Carolina Continental Line and later served as Deputy Commissary of military stores and the deputy clothier general for the state during the Revolution.[49] George Fletcher served as the purchasing commissary for Cumberland County.[50] Arthur Council raised his own company (which included twenty fellow signers) for the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge and served in the 6th North Carolina Regiment.[51] James Emmet served in the 3rd and 1st North Carolina Regiment and later rose to the rank of colonel during the war.[52] The three Carver brothers all served in the Patriot forces and James Gee fought for both Gen. Francis Marion at the battle of Eutaw Springs and with Gen. Nathanael Greene at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, almost dying at Eutaw, where a musket ball shot off his hat.[53]

The men and families of the Cumberland Association risked much for the cause of independence during the Revolution, truly living up to the statement in the Association to “go forth and be ready to sacrifice our lives and fortunes to secure her freedom and safety.”

This project was supported through a grant from America 250 NC, a program of the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

[1] “Liberty Point Declaration of Independence,” Historical Markers Database, www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=24431.

[2] Jack Crane, “The Signing of the Liberty Point Resolves,” Fayetteville Observer, June 22, 1975, 1b.

[3] “Association adopted and signed by the Committees of the District of Wilmington, in North-Carolina,” in American Archives: Documents of the American Revolutionary Period, comp. Peter Force, vol. 2, doc. ID S4-V2-P01-sp32-D0392, Northern Illinois University Digital Library, digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A80845.

[4] This is taken from a forthcoming publication by the Cumberland County Public Library’s Local & State History Department on the Liberty Point Resolves that is part of an America 250 NC grant, from the NC Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

[5] The Colonial and State Records of North Carolina (CSR), vol. 10, 1775-1776, ed. William L. Saunders (Raleigh, NC, 1890), 29-30.

[6] Leora H. McEachern and Isabel M. Williams, ed, Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee Minutes 1774-1776, (Wilmington-New Hanover County American Revolution Bi-centennial Association: 1974), xxiii-xxiv.

[7] Farquard Campbell, Thomas Rutherford, Alexander McKay and James Hepburn. CSR, 10:594-595.

[8] Robert O. DeMond, The Loyalists in North Carolina during the Revolution (Archon Books, 1964), 59.

[9] DeMond, The Loyalists in North Carolina, 57, drawing on CSR 11: xviii; CSR 24:10-11.

[10] William Henry Foote, Sketches of North Carolina, Historical and Biographical, Illustrative of the Principles of a Portion of Her Early Settlers (Robert Carter, 1846), 142.

[11] “Continental Association, 20 October 1774,” Founders Online, National Archives, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0094.

[12] “Continental Association, 20 October 1774”; Alan D. Watson, “The Committees of Safety and the Coming of the American Revolution in North Carolina, 1774-1776,” The North Carolina Historical Review, Vol. 73, no.2 (April 1996), 132.

[13] McEachern and Williams, Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee Minutes, 1.

[14] Hugh T. Lefler, History of North Carolina, vol. 1 (Lewis Historical, 1956), 212; Milton Ready, The Tar Heel State: A New History of North Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 2020), 79.

[15] McEachern and Williams, Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee Minutes, 8.

[16] Ibid., xix.

[17] CSR, 10:24-25. The minutes of other committees make references to the “Committee of Cross Creek,” with Cornelius Harnett writing to them to secure Gunpowder at times.

[18] McEachern and Williams, Wilmington-New Hanover Safety Committee Minutes, 45; William C. Fields, ed., Abstracts of Minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions of Cumberland County, vol. 1, October 1755-January 1779 (Cumberland County Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 265.

[19] CSR, 9:1205, 1202.

[20] CSR, 9: 1211.

[21] See CSR 9:1229-1239.

[22] McEachern and Williams, Safety Committee Minutes, 26.

[23] There is still a debate today about whether the Mecklenburg Declaration happened or not. For more, see: Scott Syfert, The First American Declaration of Independence?: The Disputed History of the Mecklenburg Declaration of May 20, 1775 (McFarland & Company, 2014).

[24] CSR, 10:10.

[25] CSR, 10:16-19; McEachern and Williams, Safety Committee Minutes, 29-33.

[26] McEachern and Williams, Safety Committee Minutes, 31.

[27] Ibid., 31.

[28] Watson, “The Committees of Safety and the Coming of the American Revolution in North Carolina, 1774-1776,” 143; CSR 10:161-164.

[29] CSR, 10:163.

[30] Compare CSR, 10:16-29 for New Hanover’s to 10:29-30 for Cumberland.

[31] CSR, 10:162; Hershel Parker, “The Tryon County Patriots of 1775 and Their “Association,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 11, 2014, allthingsliberty.com/2014/08/the-tryon-county-patriots-of-1775-and-their-association/.

[32] Great Britain Audit Office, American Loyalists: Transcripts of the Manuscript Books and Papers of the Commission of Enquiry into the Losses and Services of American Loyalists, Volume 47 (1783-1790, transcribed 1900), 194, 282.

[33] Data compiled from Coldham, American Migrations, 609-653.

[34] Brunswick, Duplin, Onslow and Bladen counties ‘signed onto’ the second half of the New Hanover-Wilmington Association on June 19: “We, then, the Committees of the counties of New Hanover, Brunswick, Bladen, Duplin and Onslow, in order to prevent the pernicious influence of the said Proclamation …” (CSR 10: 27). Combined, those counties had another 48 Loyalist claims filed: 35 from Bladen, 12 from Brunswick and 1 from Duplin Counties. This data was compiled from Coldham, American Migrations, 609-653. Since these counties did not independently draw up their own association but instead were present at the New Hanover meeting on June 19 and agreed to it, they are not included in this table.

[35] This includes four who lived in what is now Moore County.

[36] CSR, 10:594-595; DeMond, The Loyalists in North Carolina, 80-81. These four individuals were the only representatives from Cumberland during the four Provincial Congresses, except for Alexander McAllister, at the third Provincial Congress, and David Smith, who was a member of the fourth Provincial Congress. CSR 9:1042, 1178, 10:165, 500, 914.

[37] William C. Fields, ed., Abstracts of Minutes of the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions of Cumberland County, vol. 1, October 1755-January 1779 (Cumberland County Bicentennial Commission, 1977), 89, 103, 121, 146, 168, 202, 229, 252.

[38] Fields, Abstracts of Minutes, 220; CSR, 22:413; CSR, 7:118.

[39] CSR, 10:452.

[40] Hugh F. Rankin, The Moore’s Creek Bridge Campaign, 1776 (Currie, North Carolina: Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 1996), 19.

[41] Peter Wilson Coldham, American Migrations 1765-1799 (Genealogical Publishing Company, 2000), 609-653.

[42] Hugh McDonald Papers, record ID PC.1178, State Archives of NC, digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/hugh-mcdonald-paper-n.d./411569, 12; Eli Caruthers, The Old North State Volume 2, 1856, 265-266.

[43] Hugh McDonald Papers, record ID PC.1178, State Archives of NC, digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/hugh-mcdonald-paper-n.d./411569, 12.

[44] CSR, 22: 566-67; 570-71.

[45] E.W. Caruthers, Revolutionary Incidents: And Sketches of Character, Chiefly in the “Old North State” (Hayes & Zell: 1854), 430-31.

[46] G. W. Lawrence, “The Liberty Point Declaration,” The Observer (Fayetteville), June 3, 1909.

[47] This is compiled for a forthcoming publication by the Cumberland County Public Library on the Liberty Point Resolves as part of an America 250 NC Grant.

[48] Blackwell P. Robinson, A History of Moore County North Carolina 1747-1848 (Moore County Historical Association: 1956), 91.

[49] J. D. Lewis, NC Patriots 1775-1783: Their Own Words, vol. 1, The NC Continental Line (Published by the author, 2012), 3; CSR, 13:903-904.

[50] J. D. Lewis, NC Patriots 1775-1783: Their Own Words, vol. 2, The Provincial and State Troops (Published by the author, 2012), pt. 1, 377, and pt. 2, 303.

[51] J. D. Lewis, “Capt. Arthur Council,” Carolana, 2013, carolana.com/NC/Revolution/patriots_nc_capt_ arthur_council.html; CSR, 22:411-412.

[52] NC DAR, Roster of Soldiers, 34.

[53] The Carver information is in the forthcoming Cumberland County Public Library publication “The Patriot Gee and His Brave Wife,” February 10, 1905; William Willis Boddie, Marion’s Men: A List of Twenty-Five Hundred (Heisser Printing, 1938), 2; W. J. Fletcher, “The Gees of Cumberland County, North Carolina,” The Gee Family: Descendants of Charles Gee (d. 1709) and Hannah Gee (d. 1728) of Virginia (Tuttle Publishing), 1937, 101.

Recent Articles

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

The Killing of Jane McCrea

Recent Comments

"The Tryon County Patriots..."

Just stumbled upon this Tryon Assoc signers article from 8+years ago. Col...

"The Killing of Jane..."

Jane lived in the area of Ft. Edward, the seat of the...

"The American Princeps Civitatis:..."

I enjoyed this excellent article, thank you very much.