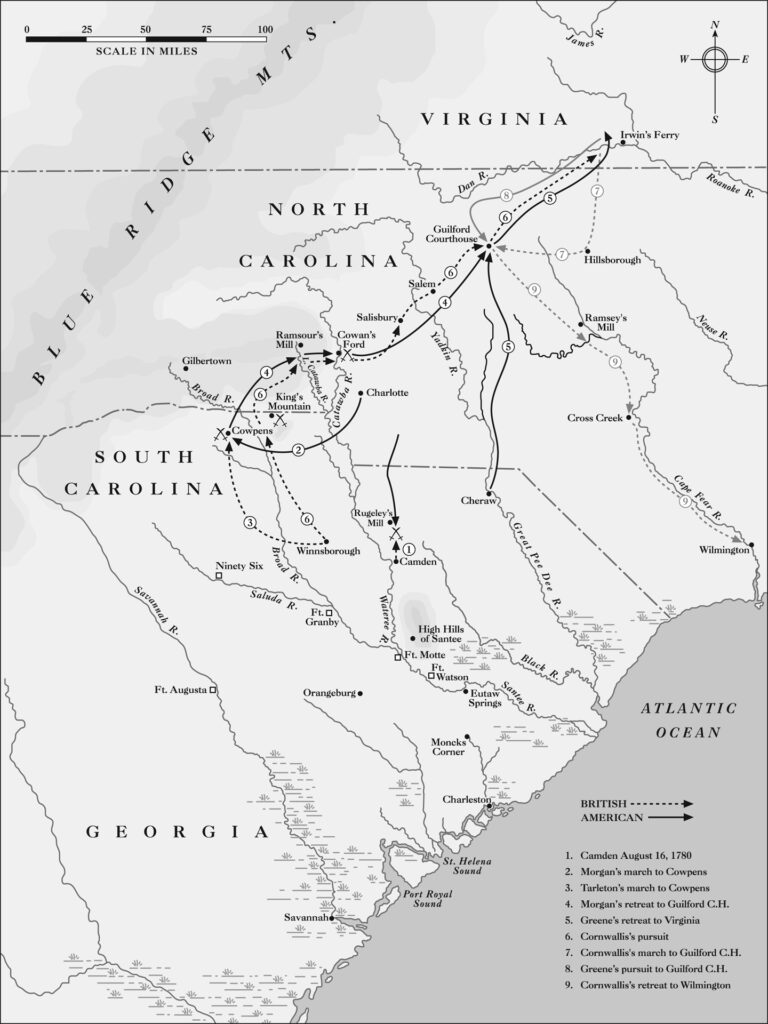

The Race to the Dan is the name given to the campaign of maneuver and retreat that followed the Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781.[1] The major event in the campaign was the single confrontation of the opposing armies at the fords of the Catawba River on February 1. In the traditional view of the engagement at the Catawba, the American commander, Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, coldly committed the militia to a hopeless defense of the river while he quietly extricated his Continentals from danger. An examination of the traditional view of the battle and Greene’s conduct in dealing with his militia subordinates suggests a different interpretation.

Brig. Gen. Daniel Morgan had defeated a detachment of 1,000 British soldiers at the Battle of Cowpens. Morgan realized he did not muster the strength to contest the main British army under Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis that was waiting nearby. Morgan took his 1,000 men and 600 British prisoners north, then northeast, ultimately heading for safety and supplies in Virginia.

Rivers, swollen in the winter rains, were obstacles to movement for both armies. Morgan divided his force into two, one assigned the mission of managing the prisoners, the other containing most of his fighting men.[2] The two divisions, small and nimble, crossed the South Fork of the Catawba River, then paused at the main branch of the Catawba. Cornwallis, his army reinforced with 1,500 men, was slow to start and moved more ponderously. He stopped at Ramsour’s Mill on the South Fork to burn most of his wagons in an effort to pare down the plodding, elephantine nature of his large force.

At the outset of the campaign, Greene was camped near Cheraw, South Carolina. He was new to command, having arrived on December 3 to take over the southern department of the Continental army.[3] He chafed at inaction, and yearned for his chance at Cornwallis, then resting securely at his base in Winnsboro, South Carolina. The Race to the Dan was a stream arising from several wells. One was Cornwallis’s decision to pursue the retreating Morgan, motivated in part, at least, by his desire to recover the British soldiers captured at Cowpens. A second was Greene’s intention to fight Cornwallis.[4] Greene had recently served in the north as a staff officer to George Washington, and longed to earn his spurs in independent command.

Morgan’s report of Cowpens, dated January 19, reached Greene on January 23.[5] News of the victory was cheering, but Morgan told Greene nothing of Cornwallis’s movements.[6] Morgan’s next letter, dated January 23, was a spike to action for Greene. This letter reported the kind of opportunity Greene had wanted: Cornwallis had left his base in South Carolina and was in pursuit of Morgan across North Carolina.[7] Greene received Morgan’s letter on January 27.[8] The next day he departed with a small escort for Morgan’s position at Sherrills Ford on the Catawba River, north of Charlotte, North Carolina.[9]

Greene arrived on January 30 to find a fluid tactical situation.[10] Cornwallis had sent a detachment probing eastward from Ramsour’s Mills and was expected at the river any day.[11] The militia commander, Brig. Gen. William L. Davidson, sent a cavalry reconnaissance to the western side of the river to look for the advancing British.[12] The two divisions of Morgan’s army crossed the river independently, then joined at Sherrills Ford. The British prisoners continued northeast under a militia guard.[13] Morgan tasked Davidson with guarding the river crossings below Sherrills Ford.[14]

It was a tribute to Morgan’s acumen that he fought Cowpens with an army that included a huge militia component. The best accounting gave Morgan only 290 regular infantry under John Eager Howard, and 80 regular cavalry under William Washington, a total of 370 men.[15] There were casualties among the Continentals at Cowpens, leaving Morgan with 350 regulars on the Catawba. Joseph Graham, the author of the most detailed memoirs of the fighting on the Catawba, claimed that before Greene arrived, Morgan “sent on the troops under his command with Colonel Howard directly towards Salisbury.”[16]

Salisbury lay thirty miles east of the Catawba River. The regular infantry in Salisbury was two days’ march from the British crossing the river. More to the point, it was two days away from any ability to support the American militia posted on the Catawba fords.

As Graham told the story, Greene arrived, met with Morgan and Davidson, then sent Washington to follow Howard on the road to Salisbury.[17] The militia would defend the river crossings by themselves. The Continentals would rest safely in Salisbury. Cornwallis, crossing on February 1, would meet only the militia.[18]

Graham’s narrative became the focus of controversy. Many later authors resisted the idea that the American commander left the militia alone to defend the river. After all, if the British were too dangerous for the Continentals, why were the militia ordered to remain, alone and isolated, an island of amateurs in a sea of professionals? This was a valid question, but as bad as things looked, Greene was about to make them much worse.

Graham’s narrative became the focus of controversy. Many later authors resisted the idea that the American commander left the militia alone to defend the river. After all, if the British were too dangerous for the Continentals, why were the militia ordered to remain, alone and isolated, an island of amateurs in a sea of professionals? This was a valid question, but as bad as things looked, Greene was about to make them much worse.

Greene arrived at the last minute, literally as the British were about to cross the river. This was not due to any fault of his own. Morgan’s second letter was his first intelligence of Cornwallis’s chase of Morgan. When he arrived, he inherited the tactical situation on the Catawba. Morgan had issued orders not knowing when, or whether, Greene would arrive. Greene accepted Morgan’s dispositions and took steps to amplify what Morgan had done. Greene faced an army of 2,700 British regulars, American Provincials, and German auxiliaries.[19] He had 350 regulars and 800 militia.[20] Greene immediately sent letters to three prominent militia commanders, Thomas Sumter, Isaac Shelby, and William Campbell, asking them to bring as many men as they could raise to the Catawba fords.[21]

When Greene left Cheraw, he left his army under the command of Brig. Gen. Isaac Huger. His orders to Huger on departing Cheraw were verbal, and therefore subject to some question. William Johnson, Greene’s first biographer, asserted Greene had ordered Huger to take the army to Salisbury.[22] Greene’s next order was in writing. On January 30, he unequivocally ordered Huger to Salisbury.[23] There is no order from Greene directing Huger to defend the river.

Greene’s letters of January 30 continued Morgan’s template: militia to the river, Continentals to the rear. Greene faced impossible odds. Although he requested help from three militia commanders, he soon realized there was no way they could respond in time to provide any benefit in defending the river crossings. Acknowledging defeat before his army could be destroyed in a futile effort to resist the crossing, Graham asserted that Greene joined in Morgan’s decision to abandon the river. Morgan had sent the regular infantry to Salisbury on January 30. Greene then sent the Continental cavalry rearward after he arrived. Both moves occurred before the British crossed on February 1.

Greene put the historians following in Graham’s wake in a terrible predicament. The problem arose in Greene’s dealings with the militia. Greene quickly and correctly assessed his tactical problems. On January 31, he reported to Congress:

The enemy are in force and appear determined to penetrate the Country, nor can I see the least prospect of opposing them with the little force we have, naked and distressed as we are for want of provision and forage. Our numbers are greatly inferior to the enemy’s when collected and joined by all the Militia in the field, or that we have even a prospect of getting.[24]

Not convinced he had made his point, he spelled it out: “The difference in the equipment and discipline of the troops give the enemy such a decided superiority that we cannot hope for any thing but a defeat.”

Greene’s pessimism formed the background to his actions with the militia. On January 31, he told Congress, “the fords are so numerous upon this river and our force so small it will be impossible to prevent their passing.”[25] The same day, he communicated a vastly different message to the local militia. He chided them for what saw as a tepid response to recruiting. Davidson’s 800 men were not enough to make a dent against Cornwallis, and he told them so: “the inattention to his call and the backwardness of the people is unaccountable.”[26] He made sure they grasped the nature of the problem: “if . . . you neglect to take the field and suffer the enemy to run over the Country you will deserve the miseries ever inseparable from slavery.”

Greene’s plans for the militia diverged sharply from his plans for the Continentals. He made this point crystal clear to the militia officers:

Let me conjure you, my countrymen, to fly to arms and repair to Head Quarters without loss of time and bring with you ten days provision . . . If you do not face the approaching danger your Country is inevitably lost. On the contrary if you repair to arms and confine yourselves to the duties of the field Lord Cornwallis must certainly be ruined.[27]

Greene, entirely candid with Congress, was much less so with the militia. Graham insisted Greene had no intention of risking a single Continental in a hopeless defense of the Catawba fords, a position strongly supported by the general’s letters. The militia would face the British unassisted. Thus far, Greene’s urgings to the militia have painted him in a difficult light. But, it was his next statement that magnified the discomfort in later generations.

Without betraying a trace of hesitation, Greene assured the militia of plentiful support: “The Continental Army is marching with all possible dispatch from the Pedee to this place.” Everything in the record we have seen—Graham’s eyewitness testimony as much as Greene’s correspondence—paints this statement as a lie. As he wrote this line, the Continental army was in two groups. Graham placed one marching away from the river to Salisbury; Greene’s letters placed the other marching toward Mask’s Ferry, with orders to proceed to Salisbury. No one had orders to march to the river. Greene was raised a Quaker and usually gets high marks for his ethics.[28] How, then, do we reconcile the idea of an ethical general committing to a course of action so Machiavellian?

Graham’s view of Greene’s actions on the Catawba fed into the views, held by most historians, of Greene as the master strategist of the southern war: here was a man willing to sacrifice the militia in order to accomplish the larger, strategic goal. In actuality, there was another, much more mundane force at work. In a word, Greene, new to the job, made rookie mistakes. His performance as a master strategist would have to wait, because in the short run, he was the new guy indulging a slow slog through a series of poor decisions.

There are few memoirs or pension depositions by Continentals shedding any light on Greene’s decisions. Two Delaware soldiers painted Greene entirely differently from the traditional picture. Robert Kirkwood was the commander of the Delaware corps, reduced to company size by illness and combat losses. In his orderly book, he recorded arrival at the Catawba on January 23. His next entry was on February 1: “March’d to Col. Locke,” a reference to the home of Francis Locke, a militia commander living a few miles from Salisbury.[29] Kirkwood was a master of minimalism, but even with this in mind, he made it clear the Continentals moved east on February 1, the day of the British river crossing, not the night before.[30] His sergeant major, William Seymour, kept a log with better detail. Seymour related more of what happened. After arriving at the river on January 23, the Continentals took a position at Sherrills Ford:

We remained on this ground until 1 February, waiting the motion of the enemy, who this day crossed the river lower down than where we lay, and coming unawares on the militia commanded by Genl. Davidson, on which ensued a smart skirmish . . . We marched off this place for Salisbury on the first of February.[31]

Kirkwood and Seymour attested to the fact that Graham was wrong. Greene did not abandon the militia to the savagery of a professional army more than three times more numerous. The traditional view of a shrewd Greene manipulating men and events falls short of the more prosaic reality. Greene deployed the Continentals at a ford on the river, withdrawing them only after learning the British had crossed elsewhere.

The Catawba River had half a dozen fords in the area of operations of the Race to the Dan. Of these, Sherrills Ford was the northernmost. Cornwallis ultimately crossed at the next two in line south, Beatties and Cowan’s, but Cornwallis maneuvered his army so as to deceive the Americans on his intended crossings.[32]

The position of Sherrills Ford affected deployments by both Morgan and Greene. Morgan, thinking he divined Cornwallis’s plan, originally decided to “Leave Open” Sherrills Ford and defend only the downstream river crossings.[33] Morgan, again trying to decide where Cornwallis would cross, revised his plan. On January 29, he wrote that he kept the Continentals at Sherrills Ford.[34] He had moved Sherrills Ford from last to first place in priority. Rather than leave it undefended as an unlikely target for Cornwallis, he moved it to most likely, and defended it with his best soldiers.

Greene inherited Morgan’s deployments, and likely his thinking. Greene kept the Continentals at Sherrills Ford. As luck would have it, and from the American standpoint it was pure luck, Cornwallis crossed downstream, bypassing the Continentals. Greene then withdrew the Continentals toward Salisbury. Graham, not a party to the councils of strategy between the three generals, misapprehended everything, the planning as well as the execution.[35]

For his part, Greene left inconsistent records. New to independent command, his reporting to Congress was unpolished and imperfect. A commander telling the civilian authorities he expected only defeat was asking for trouble. If things were so bad, why was he risking men and resources in a futile attempt to defend a lost cause? His reporting was a classic rookie mistake, much like his unguarded statements to the militia officers. Huger was not marching toward the Catawba River. He was marching in the direction of the river, but with orders to stop in Salisbury. In his efforts to create enthusiasm for the project, Greene overstated his case.

In the traditional view of the fighting on the Catawba, Greene emerged clever, almost diabolically so. He brilliantly maneuvered the militia to the river where they delayed the British and caused the enemy to suffer casualties, all the while allowing the regulars to escape harm, saving them for the major battle to come. The fact that he used lies and deceit was part of his aura. Greene, his gaze fixed on the mission, did whatever it took to win.

For better or worse, this traditional view does not reflect what actually happened. Greene, new in command, floundered. His letters to Sumter, Sevier, and Campbell on January 30 were absurdities in a world where Morgan expected Cornwallis to cross the river as early as January 31.[36] His misstatement to the local militia officers, that the Continental army was marching toward the Catawba, was capable of creating false hopes in men facing unimaginable danger.

Greene’s performance as a master strategist would have to wait. He had been yearning for his chance at Cornwallis and he took it. He made the worst possible beginner’s mistake: he decided to defend the river with half his army. Greene threw caution to the wind and jumped at his first opportunity to fight Cornwallis. He was saved by mere chance. Cornwallis decided to cross below Sherrills Ford. Had he decided otherwise, his juggernaut of professional soldiers, still fresh from repose in South Carolina and unbloodied in this campaign, would have crushed Greene’s army, permanently.

The fighting at the Catawba left Greene’s integrity and ethics intact. He used neither lies nor deceit in his dealings with the militia. His skills as a master strategist, however, would emerge later. At this point in his career, he was a great strategist in waiting.

[1] Some historians limit the actual “race” to the final days of the campaign, e.g., John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997), 352. For convenience, this article will use the term to cover the entire campaign. Andrew Waters, To the End of the World: Nathanael Greene, Charles Cornwallis, and the Race to the Dan (Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2020), likewise, treats the entire campaign as well.

[2] Daniel Morgan to Nathanael Greene, January 23, 1781, in Richard K. Showman, Dennis M. Conrad, Roger N. Parks, and Elizabeth C. Stevens, eds., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, vol. 7: 26 December 1780–29 March 1781 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 7:178; William A. Graham, General Joseph Graham and His Papers on North Carolina Revolutionary History (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1904), 287−288.

[3] Greene to Thaddeus Kosciuszko, December 3, 1781, in Richard K. Showman, Dennis M. Conrad, Roger N. Parks, and Elizabeth C. Stevens, eds., The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, vol. 6: 1 June 1780 –25 December 1780 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 6:515.

[4] As one example among many, Dennis Conrad, a distinguished Greene scholar, remarked on the general’s “wish to engage Cornwallis’s army,” “General Nathanael Greene: An Appraisal,” in Gregory D. Massey and Jim Piecuch, eds., General Nathanael Greene and the American Revolution in the South (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2012), 17.

[5] Greene to John Matthews, January 23, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:174.

[6] Morgan to Greene, January 19, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:152−155.

[7] Morgan to Greene, January 23, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:178.

[8] Edward Stevens to Thomas Jefferson, February 8, 1781, in Julian P. Boyd, Lyman H. Butterfield, and Mina R. Bryan, eds., The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 4: 1 October 1780 to 24 February 1781 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 4:562, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-04-02-0698.

[9] Most of the Catawba fords have a multiplicity of spellings, including, in this instance, Sherrill’s, Sherels, and Shreve’s. Beatties, mentioned below, is rendered Beattie’s, Beatty’s, and Baty’s, among others. Cowan’s Ford, the site of the major fighting, was McGowan’s in the eighteenth century.

[10] Greene to William Campbell, January 30, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:218.

[11] Morgan to Greene, January 28, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:211.

[12] Graham, General Joseph Graham, 288−289.

[13] Morgan to Greene, January 28, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:211; Graham, General Joseph Graham, 287−288.

[14] Morgan to Greene, January 28, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:211; Graham, General Joseph Graham, 288.

[15] Morgan’s biographer reported that the “army returns and muster rolls” counted 980 American soldiers at Cowpens. James Graham, The Life of General Daniel Morgan, of the Virginia Line of the Army of the United States, With Portions of His Correspondence, Compiled from Authentic Sources (New York, 1859), 295. William Johnson broke this down into the numbers shown here. William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, 2 vols. (Charleston, 1822), 1:374−377.

[16] Graham, General Joseph Graham, 288.

[17] Ibid., 289.

[18] Cornwallis to George Germain, March 17, 1781, in Ian Saberton, ed., The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre, 6 vols. (Uckfield, UK: The Navy and Military Press Ltd, 2010), 4:13.

[19] “Return of Troops at the Battle of Guilford” in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:63; “Return of Casualties in North Carolina Prior to the Battle of Guilford,” in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:62; “State of Troops Fit for Duty, 15th January to 1st April 1781,” in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:61; Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 3:11n4.

[20] The militia numbers have been hotly contested. The number in the text is from Morgan to Greene, January 29, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:215.

[21] Greene to Thomas Sumter, January 30, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:221; Greene to William Campbell, January 30, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:218; Greene to Isaac Shelby, January 30, 1781, in Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:221.

[22] Johnson, Sketches of the Life, 1:401, 413. Johnson found support in a letter from a staff officer, who reported to North Carolina’s governor that Huger had orders to proceed to Mask’s Ferry, on the Pee Dee River in North Carolina, as part of Greene’s strategy to counter an anticipated British move to Salisbury, Lewis Morris to Abner Nash, January 28, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:209.

[23] Greene to Huger, January 30, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:219−220.

[24] Greene to Samuel Huntington, January 31, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:226.

[25] Greene to Huntington, January 31, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:225.

[26] Greene to the Officers Commanding the Militia in the Salisbury District of North Carolina, January 31, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:227.

[27] Ibid., 7:228.

[28] For example, his most recent biographer praised his “virtue.” Terry Golway, Washington’s General: Nathanael Greene and the Triumph of the American Revolution (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2005), 3.

[29] Joseph Brown Turner, ed., The Journal and Order Book of Captain Robert Kirkwood of the Delaware Regiment of the Continental Line (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1910), 13.

[30] His minimalism was apparent in his account of the Battle of Cowpens, which he limited to two lines: “Jan. 16th. March’d to the Cowpens. Jan. 17th. Defeated Tarleton.”

[31] William Seymour, Journal of the Southern Expedition, 1780-1783 (Wilmington, DE: Historical Society of Delaware, 1896), 15−16.

[32] Cornwallis to Germain, March 17, 1781, in Saberton, Cornwallis Papers, 4:13.

[33] Morgan to Greene, January 28, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:211.

[34] Morgan to Greene, January 29, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:215.

[35] Graham described Greene’s meeting with Morgan and Davidson on his arrival, which he was able only to watch from a distance. A militia captain at the time, he had no entry into the councils of high command. Graham, General Joseph Graham, 289.

[36] See Morgan to Greene, March 29, 1781, in Showman et al., Papers of Nathanael Greene, 7:215, where Morgan reported Cornwallis’s main army was only ten miles distant, and “their advance is in sight.”

Recent Articles

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

This Week on Dispatches: Brady J. Crytzer on Pope Pius VI and the American Revolution

Advertising a Revolution: An Original Invoice to “The Town of Boston to Green and Russell”

Recent Comments

"The Tryon County Patriots..."

Just stumbled upon this Tryon Assoc signers article from 8+years ago. Col...

"The Killing of Jane..."

Jane lived in the area of Ft. Edward, the seat of the...

"The American Princeps Civitatis:..."

I enjoyed this excellent article, thank you very much.