On the morning of November 18, 1780, Maj. Archibald McArthur’s troops, a battalion of the 71st and a detachment of the 63rd Regiments of Foot, were washing their clothes and bathing in the still-warm waters of the Broad River in central South Carolina. Stationed at Shirer’s Ferry, their responsibility was to guard the ferry to ensure communication between Lord Cornwallis in Winnsboro with the post at Ninety-Six as well as to protect the grist mills along the river that provided flour for Cornwallis’s encampment fifteen or sixteen miles further in.

After the Patriot disaster in Charlestown, followed in August by the destruction of an American army at Camden, all that was left of the Rebel cause in South Carolina consisted of the partisan bands led by Thomas Sumter, Andrew Pickens, and Francis Marion. General Cornwallis had recently attempted to utilize Charlotte as a staging base for an anticipated fall campaign to “pacify” the still unruly rebels in the Piedmont. Moving from the Waxhaws to Charlotte on September 27, 1780, the British immediately encountered evidence of the inveterate hostility of the inland Presbyterian communities to the Crown starting with the bloodying of an advance guard as they rode into the Queen City.

Shortly thereafter, Loyalist forces were annihilated at King’s Mountain only about thirty miles away from Charlotte. Moreover, the supply line back to Camden, even with local forage, was tenuous. Consequently, Lord Cornwallis retreated to what he thought would be a more supportive location, the farming community at Winnsboro. The Fall Campaign died with the withdrawal.

Major McArthur’s soldiers were nearing the end of their bathing and washing when some armed men appeared across the Broad River on its western side. These unknown men began taking potshots of the not yet completely dry or clothed British soldiers. The few of McArthur’s men still in the water grabbed their clothes and quickly scurried out of the water to safety.

Major McArthur began assembling a force of one hundred and fifty men to promptly chastise the impertinence of these interlopers. Before they could set off in pursuit, an additional body of troops arrived: Banastre Tarleton and his British Legion. Tarleton promptly sent part of his force across the Broad River via the ferry and part a few miles down river at a nearby shoals. After crossing, Tarleton’s Legion went in pursuit of the enemy: Thomas Sumter and the South Carolina Militia.

The battle that followed, Blackstock’s Farm, ended in a stinging rebuke to Tarleton. The impetuousness of “that boy” led to severe loss to the Legion and, though wounded, the escape of Sumter meant he would rise to fight again. This was an ill-omened passage for Tarleton. He was to pass by Shirer’s Ferry one more time: on his way in January 1781 to his brigade’s destruction at the Cowpens, largely as a result of the impetuosity he exhibited at Blackstock’s.

But where was Shirer’s Ferry? It would seem that the location of such an establishment would be easily located from the various histories and maps from the time. However, the exact location disappeared for some fairly simple reasons. This report intends to identify where it was located.

Shirer’s Ferry

The early to middle 1700s saw colonization of the interior parts of South Carolina. The town of Ninety-Six was established to facilitate trading with the Cherokee Indian Nation. During this time, an influx of immigrants from various Protestant German-speaking principalities settled in the area between the Saluda and Broad Rivers. This area became known as the Dutch (corruption of “Deutsch”) Fork. In the same area, a Native American settlement called the Congarees occupied a central and convenient point at the junction of the Saluda and Broad Rivers. Northward were settlements stretching into North Carolina that used trading routes to Charlestown along the Broad River that passed through.

A crossing of the Broad River from the upper part of the Province to the Congarees was needed to support the growth of the Dutch Fork. Roads, ferries, causeways and other infrastructure were regulated by the South Carolina General Assembly which vested these state establishments, setting tolls, maintenance conditions, and the like. The first ferry on Broad River was established by the General Assembly in 1770.[1]

The ferry was on granted land given to Martin Scheurer, who later was known by the Anglicized name of Martin Shirer. His wife Elizabeth Scheurer also was given a grant of land used by the ferry. They had two children, Isaiah and Barbara. The ferry was granted for a term of fourteen years, a period that extended past the future British military occupation.

The ferry apparently prospered until 1773 when Elizabeth Shirer passed away, leaving all her property to her children as, according to her probated will, her husband Martin had predeceased her. There followed a period until the British troops arrived that the ferry could possibly have been run for the children by Caspar “Bierley.” There are earlier references to interactions between the Scheurers and the “Byerleys” in the sub-allocation of land from the grants as well as in Elizabeth Shirer’s will. Ultimately, vesting of the ferry was to run out in 1784, requiring general assembly action to continue.

As the time for re-vesting approached, the British occupation of the province caused a hiatus in general assembly proceedings. In 1785 Shirer’s ferry was temporarily put into the hands of Minor Winn for three years, during which time Isaiah Shirer and his sister Barbara sold their property to Richard Strother, who owned property further up the river at another spot conducive to ferry operation. (The ferry has had several alternate names applied to it, along with Shirer: Shirar, Shiror, Brierley, Byerley and Bierley. The possibility that the ferry was run under the name Brierley at the time of the British occupation likely stems from the operation of the ferry after the death of Elizabeth Shirer.)

Soon thereafter Richard Strother died intestate and his property was divided by the probate court into several parts. His daughter Nancy inherited one of the grants given to Martin Shirer and his wife. Later she married George Ruff, in whom the General Assembly revested the ferry. In time, the ferry became the property of one Hughey in the mid-1800s, apparently without vesting as a public ferry, and then disappeared altogether. Roads on contemporaneous 1800s-1900s maps were named Ruff’s Ferry in Fairfild County and Hughey’s Ferry in Newberry County.

Locating Shirer’s Ferry

Plats exist for two grants on Broad River for the Shirers, but plats are generally without the necessary information to place them with respect to geo-locatable surface features. The bearings define the property well enough, but they are not in any geographic coordinate system. Creeks, rivers, hills, towns or other physical features are almost always missing or vestigial. Without these physical identifying features, placing the plats on an actual map is fanciful at best. Additional sources must be searched to geo-locate Shirer’s Ferry.

An obvious place to start is the British military records from the time. Considerable useful information concerning Shirer’s Ferry as well as military activities nearby along the Broad River is available in the military correspondence of General Cornwallis.

On November 12, 1780, Cornwallis ordered a detachment from 63rd and a battalion of the 71st Regiments of Foot to be posted at Shirer’s Ferry. Major McArthur stated that he was at the ferry and that Lt. John Money arrived the previous day and spent the night of the previous evening at Sommers Mill, three miles down the river.[2]

Similar to the situation with plats, where these two features are would be open to speculation. In this case there were maps of the river and environs that might be expected to include cadastral features like towns, roads, structures, churches, etc. The problem is that accurate maps with proper longitude and latitude were generally scarce, and South Carolina, being recently settled, had few roads, villages, towns, etc, with few features identified.

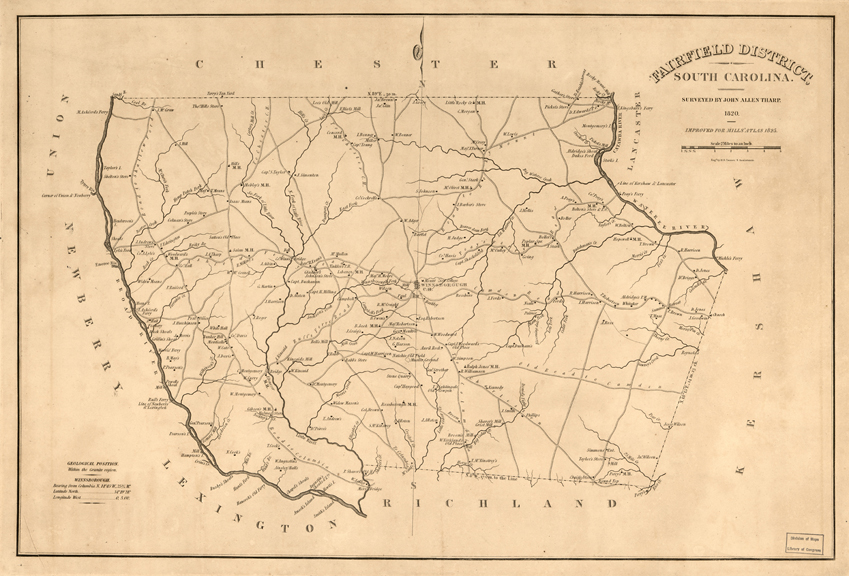

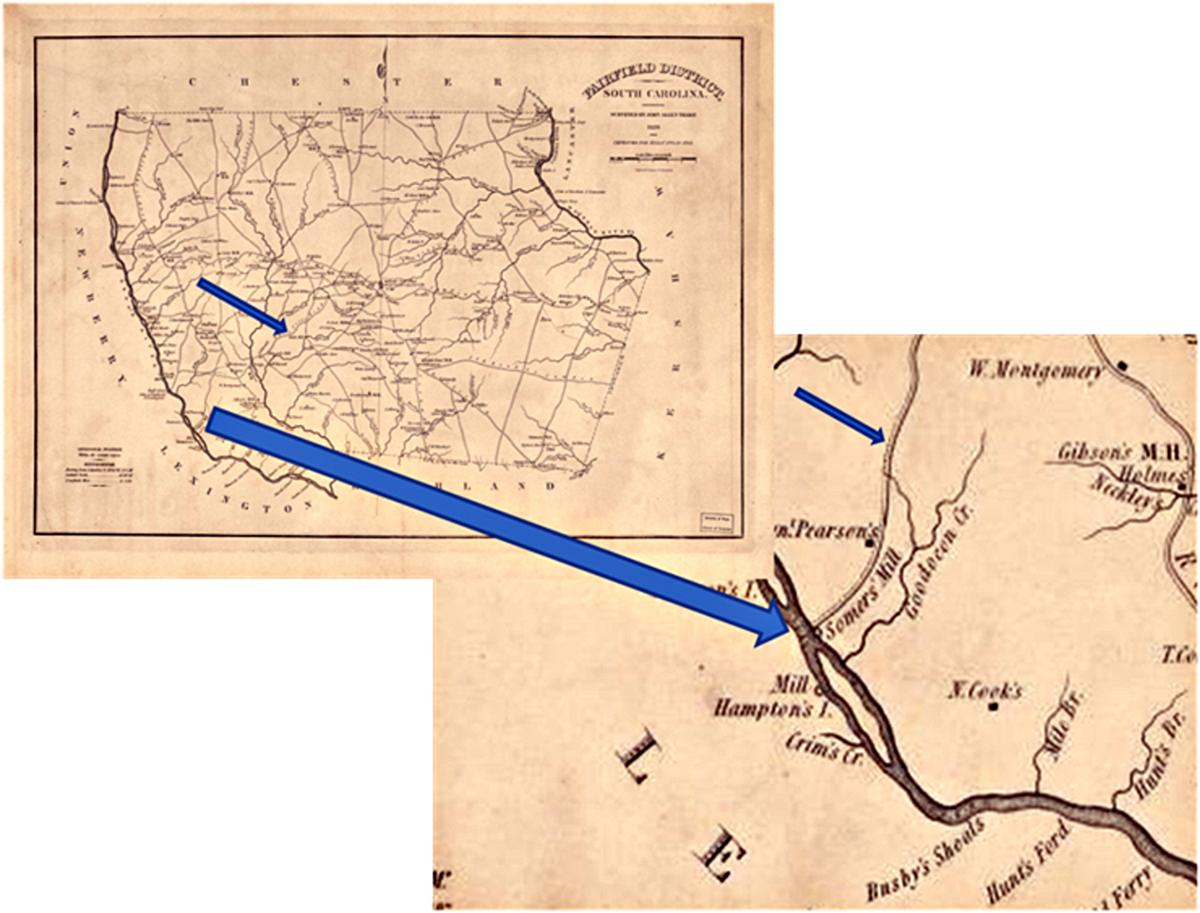

In 1816-1820, the State of South Carolina determined to have the state surveyed. The General Assembly ordered surveys, an effort lead by John Wilson. From these surveys the noted Mills 1825 Atlas was produced. Figure 1 shows the Mills maps for Fairfield County shows the town of Winnsboro, Lord Cornwallis’ headquarters. Figure 2 has the Fairfield County map; overlaid is a blow-up of the area in the southwest corner of the county.

Shirer’s Ferry passed from the Richard Strother family to George Ruff’s with his marriage to Rachel Strother. Ruff’s Ferry Road can be seen leading from Winnsboro to the Broad River and crossing between the “Newberry” and “Lexington” labels in the bottom left of the blown-up insert. Moreover, there are two mills identified further down the river, one “Somers Mill” and the other just “Mill” near “Hampton’s I[sland].” It should be noted that Lord Cornwallis was concerned about supplies for his troops at Winnsboro and was aware that of more than one mill in the area. There are references in Cornwallis’s correspondence of occasional damage to the mills on the south side of Broad River that were susceptible to marauders in that no-man’s land.

What makes Somer’s Mill and Shirer’s Ferry identifiable is the statement “three miles lower down the river.” We have the river, two features, a specified distance between the two features and a properly surveyed map. These facts enable quantitative analysis using Geographical Information System tools. Before applying GIS to finding the ferry location, it is important to confirm that this mill was indeed the one under British protection.

Sommer’s Mill and Shoals in Local Lore

In 1954, Claude and Irene Neuffer began publishing, via the Department of English at the University of South Carolina, a collection of historical names known in the state of South Carolina. Claude and Irene Neuffer’s Names in South Carolina assembled the various names and associations for twelve years. The publication continued for several years later. In the various volumes are several references to mills, shoals, stores; a search finds several related in the Dutch Fork area:[3]

“Parr Shoals, originally named Somer’s Shoals for a Mr. Somer who operated a mill near the shoals in the early 1800’s, are just north”

“Although several individuals operated mills adjacent to the shoals, they remained known as Somer’s Shoals or Summer’s Shoals”

“The central figure in the Dutch Fork School of Writers, O.B. Mayer (1818-1891) sets most of his fiction in the Dutch … Fork area of his childhood and early manhood.”

“O.B. Mayer Birthplace. ‘Where I was born, and where I passed much of my early life,’ says Mayer. It was the home of his grandmother, Eve Margaret Summer Mayer (1775-?), who was the daughter of Johannes Adam Summer, Jr. (1744-1809)”

“Cohee’s Shoals. Also known later as Summer’s Shoals … Mayer located the Shoals as on Broad River midway between the points where Cannon’s and Crim’s Creeks empty into the river.”

“Lakin’s Mill. Mayer locates this mill at two places. In ‘The Easter Eggs’ (1848) it is said to be on the Fairfield County side of Broad River between Hampton’s (Number 9) and Pearson’s Islands. In The Dutch Fork, it is three-quarters of a mile below Cohee’s Shoals (Number 6) and one mile above Peak (Number 14). John Adam Summer, Sr., is said to have taken possession of this ‘mill-seat.’”

These extracts from the Names show that the name Somer or Sommer or Summer was well known in the early 1800’s Dutch Fork community on the Broad River, moreover, these names are associated with both mills and shoals which are possible crossing places on the Broad.

The GIS Synthesis

With the locations identified and their relative placement given as a fixed distance, the methods and tools of GIS can be used to locate Shirer’s Ferry with respect to a properly georeferenced map. As a start, a “canvas” of properly georeferenced features must be found. Somewhat immutable features are hydrologic: streams, creeks, rivers, lakes, etc. Assuming that the original maps were accurately done, the national hydrology data sets of the United States Geological Survey are a good starting place. These maps of the United States contain carefully located hydrological features across the country. They are available in digital form at high resolution, ideal for use in GIS mapping applications.

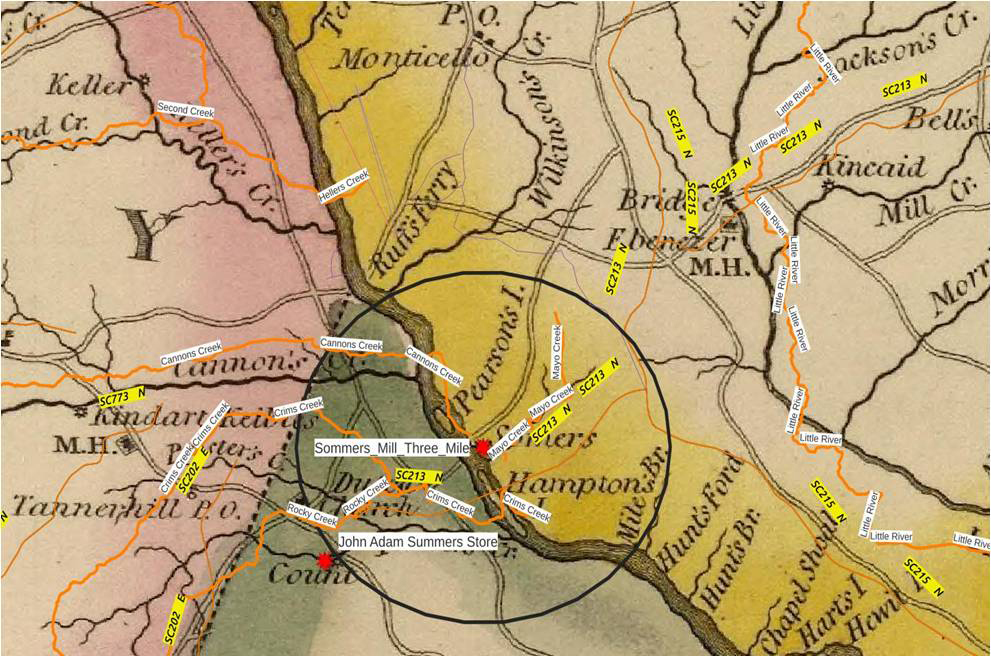

With the water features, the Wilson Surveys or Mills maps can be laid out to make a basis for location of roads, towns, etc. The process of warping, rotating and digital conversion is called georeferencing. The georeferencing technique consists of several steps. Digital copies of the Wilson or Mills maps (in a geographical coordinate system, i.e. latitude and longitude) are obtained, as well as the hydrological map. Then a set of reference points are found on the hydrology map – these could be junctions of creek and river, springs, etc. The same location is identified on the target map and selected. This process is continued until a small database is created, relating objects on the target map to where they should be on a properly georeferenced canvas.

With enough points chosen for the warping equation to be used, all points on the target map are transformed to produce a new digitized map, with the target map features “mathematically moved” to new coordinates. The new map is then saved and used as the correctly projected base map, matching surface features.

The McArthur information that Somer’s Mill was three miles further down river is used to generate a map feature that is three miles in radius with center located on the re-projected Mills map where Somer’s Mill is indicated.

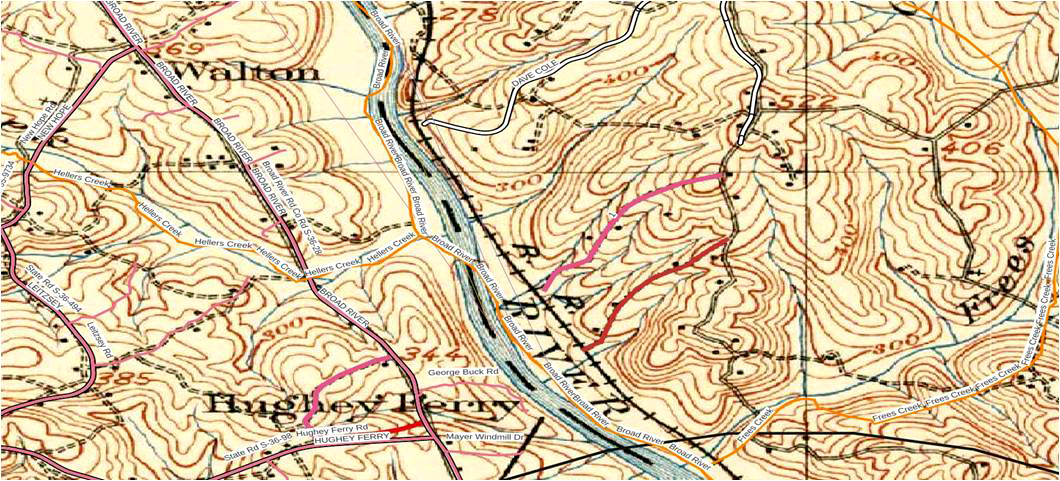

The map now shows that upriver from Somers Mill as shown on the Mills map is Ruff’s Ferry. It is above Cannon’s Creek and below Heller’s Creek on the west side of Broad River and at Wilkinsons’s Creek. This latter has been a point of confusion for the search for Shirer’s Ferry, since Wilkinson’s Creek has been found on several plats, indicating paths to Shirer’s Ferry. Yet modern maps put Wilkinsons’s Creek much further up Broad River. The reason is that the Wilson-Mills maps have occasional errors; the correct name for the creek is Free’s Creek. Wilkinson’s Creek is close to Terrible Creek, and above Heller’s Creek, which can be seen in Figure 3.

Relation to the Folklore

There are several instances of consistency in the Names in South Carolina excerpts. Somer’s Mill was above Crim Creek and below Cannon’s Creek. Laken’s Mill is given as the original name for Somer’s Mill and is located between Hampton Island and Pearson’s Island, consistent with the Wilson-Mills maps. So there is strong consistency between the local traditional history and the map representation. There were known to be additional mills in this area, with one shown on the map and referred to in the Names in South Carolina excerpts.

Moving to the Modern

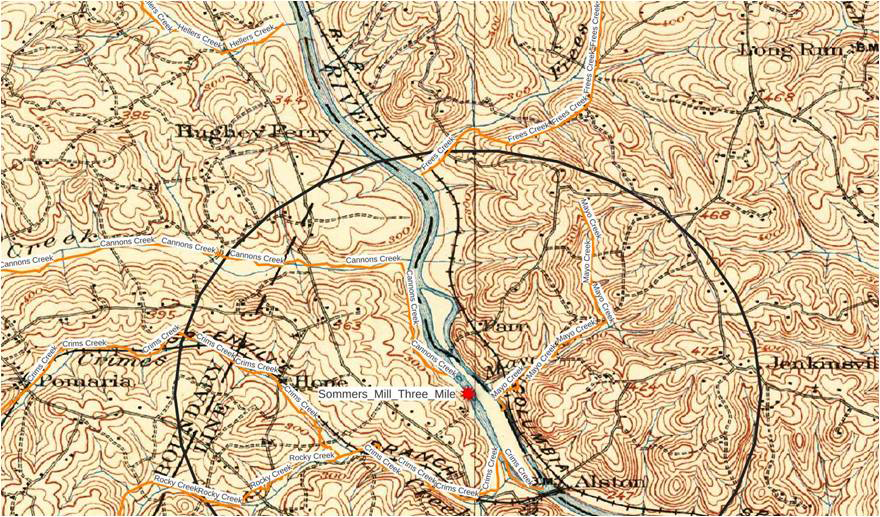

Topographic maps of certain parts of South Carolina began to be produced in the early 1900s. These maps used proper projections and accurate coordinates. The area around Columbia, South Carolina was mapped in early 1900s by the U.S. Geological Survey. These maps, of very high quality, contain residual roads and road beds from the past as well as many roads that are identifiable in their modern form. One example is the 1904 Columbia Quadrangle shown in Figure 4.

The 1904 topographic map was also georeferenced against the hydrology features in the area. This map is reproduced in Figure 4 with the Somer’s Mill location superimposed as well as the three-mile fixed distance. Again the ellipticity of the three mile locus comes from the fact that geographical (longitude and latitude) transforms distances differently in vertical direction, latitude compared to horizontal, longitude.

What the Map Tells Us

What can we infer from this placement of Somer’s Mill, the three-mile locus and the location of Shirar’s (Brierley’s) Ferry? The crossing of the three-mile locus over Broad River to the north occurs at the properly named Free’s Creek. Moreover, a road identified as Hughey Ferry is indicated on the 1904 map. We know that Hughey Ferry Road across the river on the Fairfield County side was known as Ruff’s Ferry Road from a close inspection of the original Mills map. We also know that George Ruff operated a ferry that came to him through his wife Rachel, who in turn inherited it from the original Shirer property as part of the Strother estate. The Shirers operated one ferry granted in 1770 from their two properties originally granted to Martin and Elizabeth Shirer (Scheurer.)

The 1904 map can be further enhanced by overlaying modern roads with names to produce the map in Figure 5. On this map, Hughey Ferry road is still seen as the modern name of the identified road. Two roads have been notionally laid out on the east side of the river and two on the west side, near Hughey Ferry Road along paths that can be seen on the 1904 topographical map. These four roads do not exist as modern roads but tracks in the same location appear in aerial photographs.

The major and historic “River Road” known as Broad River Road is easily seen on the Mill’s map. Free’s Creek (the correct name for Wilkinson’s Creek) is also seen. The left side of the map is Newberry County, South Carolina, while the right or east side is Fairfield County. The black arc near the bottom is the locus of three miles from the identified Somer’s Mill.

Modern Location of Shirer’s Ferry

Development along the Broad River has left unchanged many of the roads originally in existence during the Revolution, although some parts have been straightened. The largest change and impediment to identification of the actual location of Shirer’s Ferry has been the installation of the Parr Hydroelectric Dam and Reservoir. An additional reservoir, Monticello Reservoir, is behind the the Broad River on the east side. Moreover, the hydroelectric dam area is also the location of the V.C. Summer Nuclear power plant in the same property, now owned by Dominion Power.

The road from the ferry to Winnsboro (and likely Lord Cornwallis’ camp) shown on the Mill’s maps as “Ruff’s Ferry Road” is today along state route SC213 N. The last section of that road approaching the old ferry is apparently under Monticello Reservoir. The old road to the north from the ferry is now called “Cole Trestle Road” and is in the power plant property.

The modern Newberry County road, Hughey Ferry Road “S-36-98”, ending at modern Broad River Road is likely the original path to the ferry, which continued a short distance on to the river. This extra distance is approximately 950 yards.

CONCLUSIONS

Banastre Tarleton crossed the Broad River at what he identified as “Brierley’s Ferry,” first in 1780 during his pursuit of Thomas Sumter that led to Tarleton’s defeat at Blackstocks Farm, and second on January 1, 1781, on his way to the Battle of Cowpens

Over time, the location of this highly significant, sometimes misnamed ferry, originally established by Martin Scheurer as “Shirer’s Ferry,” faded into obscurity. Passed to owners who maintained ferries across the Broad River near where the ferry location was, the ferry was apparently closed, reopened under other names, and then finally abandoned. Plats registered by the owners and grantees of land exist, but plats are deficient in geolocation. They almost all lack features or other landmarks that can be identified on a general map for an area. Other sources of information must be found to remedy the deficiency.

Major Archibald McArthur’s correspondence with Cornwallis gives specific distances between his location at the ferry and a local grist mill. This information, interpreted quantitatively by modern Geographical Information System analysis, leads to the conclusion that the ferry used by Banastre Tarleton known as Shirer’s or Brierley’s in his crossings of the Broad River was just above Free’s Creek on the east side of Broad River in South Carolina. The location is at Hughey’s Ferry Road, continued from its intersection with Broad River Road to the banks of the Parr Shoals Reservoir of Broad River on the Newberry County side. On the Fairfield County side the crossing is down Cole Trestle Road leading to abandoned paths to the same reservoir. The path from the ferry to Winnsboro is submerged under Monticello Reservoir at its beginning and emerges from the water as road SC213 N until near the town of Winnsboro.

There are several small roads and locations in and around the Hughey Ferry Road terminus that could be excellent spots to establish markers for Shirer’s Ferry. The maps created in this report can be used to guide the selection of suitable sites directly relatable to the Shirer’s Ferry site. This will allow the permanent recognition and identification of this newly-found location so integral to the Patriot cause in South Carolina.

Acknowledgements

This report would have not been possible without the dogged support of John Favors of the Newberry County Museum. John continued to strongly resist the location of Shirer’s Ferry at what was called Strother’s Ferry. The only excuse for the bias towards other locations was that others, such as Professor McCrady in his The Revolution in South Carolina published in 1902 identified Brierly’s as Strothers. But as always, the best excuse is no excuse at all.

[1] The Statutes At Large of South Carolina, edited by David J. McCord, Vol. 12 (Columbia, SC: A.S. Johnson, 1841), 238.

[2] Ian Saberton, The Cornwallis Papers, Vol. III (Uckfield, UK: The Naval and Military Press, 2010), 316.

[3] Names in South Carolina Vol. XXX (Winter 1983).

Recent Articles

Announcing the 2025 JAR Book of the Year Award!

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: The Present Status of the Controversy

Belonging: An Intimate History of Slavery and Family in Early New England

Recent Comments

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Interesting! Thanks, from a Charlotte NC Am Rev fan.

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

A great overview of that controversial document. I tend not to accept...

"The Mecklenburg Declaration of..."

Although a skeptic on the Mecklenburg Declaration, I think it is an...