The first objective in Lt. Gen. Earl Cornwallis’s first invasion of North Carolina was the capture of Charlotte. He intended to establish a post there, not only to control adjacent territory, but also to facilitate his communication with the south as he advanced farther.

At daybreak on September 7, 1780, accompanied by two 3-pounders, Cornwallis quit Camden, South Carolina, and marched towards Charlotte with the Royal Welch Fusiliers, the 33rd Regiment and the Volunteers of Ireland, leaving behind material numbers of their dead, sick and wounded. Two days later he reached the border settlement at the Waxhaws and was joined by Samuel Bryan’s North Carolina militia. The troops soon set up camp on Waxhaw Creek, living on wheat collected and ground from the plantations in the neighbourhood, most of which were owned by Scotch-Irish revolutionaries who had fled.

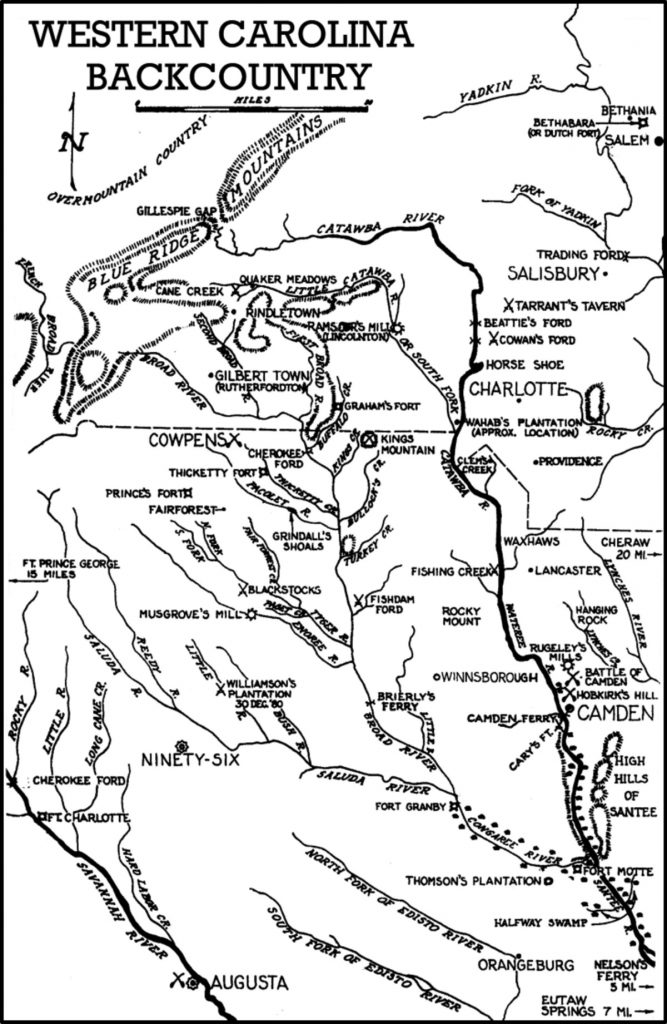

On September 8 Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton crossed the Wateree at Camden Ferry and advanced with the British Legion and a detachment of the 71st Regiment’s light troops towards White’s Mill on Fishing Creek. While there on the 17th, he fell ill of a violent attack of yellow fever. His entire corps, the command of which devolved on Major George Hanger, was now needed to protect him. Fearful that they would be attacked by enemy militia, Cornwallis dispatched his aide-de-camp, Lt. John Money, on the 22nd to report back. Money noted in his journal, “The post was such that the cavalry in case of attack could not act. Those who had carbines were dismounted and took post in a wood to the right, and every other precaution taken to strengthen the post and prevent a surprise.” The next day, much to everyone’s relief, Tarleton had become well enough to be moved by litter to Blair’s Mill on the east side of the Catawba. Crossing with him at the ford there, which was 600 yards wide and three and a half feet deep, the Legion joined Cornwallis. All in all, Tarleton’s illness was one of the main reasons for setting back the entry into Charlotte.

On the 24th the troops marched at four in the afternoon towards Charlotte. Halting at Twelve Mile Creek, they waited till the moon rose before proceeding towards Sugar Creek on the Charlotte road. No certain intelligence having been received that Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter had passed the Catawba, Col. Francis Lord Rawdon was detached with the Legion and the flank companies of the Volunteers of Ireland to attack him. On arriving at Bigger’s Ferry, they discovered that Sumter had passed the evening before and that Brig. Gens Jethro Sumner and William Lee Davidson of the North Carolina revolutionary militia had retired from McAlpine’s Creek. After taking post at the ferry, the detachment marched at daybreak on the 26th and joined the rest of the troops at the cross roads within four miles of Charlotte.

Assigned to form the van with the Legion, Hanger was later to remark, “Earl Cornwallis ordered me to be very cautious how I advanced as he expected a very large body of militia to be either in the neighbourhood or . . . Charlotte.” Skirmishing with a small party of the enemy along the Steele Creek Road, Hanger halted within sight of the village that the rest of the troops might close up, and in the meantime he endeavored to reconnoiter.

Charlotte lay on rising ground and contained about twenty houses built on two wide streets which crossed each other at right angles. At their intersection stood the court house, a frame building raised on eight brick pillars ten feet from the ground. Between them a stone wall had been erected three and a half feet high, the open basement serving as a market house. On the left of the village as Hanger faced it was an open common while on the right were one or two houses with gardens. “Determined to give his Lordship some earnest of what he might expect in North Carolina,” Lt. Col. William Richardson Davie occupied the village with his corps of 150 men and a few revolutionary militia commanded by Major Joseph Graham. One company was posted in three lines under the court house behind the stone wall whereas the rest were drawn up on either side of it or advanced behind the houses and gardens on Hanger’s right.

The Legion cavalry under Hanger’s immediate command were the first to enter the village. It was now about ten in the morning. Proceeding at a slow pace till fired on by an advanced party of the enemy, they then came on at a brisk trot to within fifty yards of the court house. There the enemy’s first line moved up to the stone wall and fired, wheeling outwards and down the flanks of the second line as it advanced. Believing the enemy was retreating, the Legion cavalry rushed up to the court house only to be met with a full fire from the enemy posted on either side of it. Immediately they wheeled about and retreated back from where they came, being fired on by the second line at the court house, but at rather too great a distance to have much effect. Hanger was freely to admit that militarily it was not his greatest day: “I acknowledge that I was guilty of an error in judgment in entering the town at all with the cavalry before I had previously searched it well with infantry, after the precaution Earl Cornwallis had given me.”

Yet Hanger did manage to retrieve the situation, as he himself explained:

We had a part of the Legion infantry mounted on inferior horses to enable them to march with the cavalry, ready to dismount and support the dragoons. These infantry of their own accord very properly had dismounted and formed before the cavalry were near out of the town. I ordered them to take possession of the houses to the right, which was executed before the light infantry and the remainder of the Legion infantry came up, who were left behind with Earl Cornwallis to march at the head of his column.

Reinforced, the Legion infantry pressed ahead under cover of the houses and gardens, exchanging a hot fire with the enemy, whose advanced parties had been withdrawn. Eventually the enemy’s position became untenable and Davie ordered a retreat by the Salisbury road. Ordered by Cornwallis to pursue with the Legion cavalry and infantry, Hanger was later to declare:

This service they performed with spirit, alacrity, and success. We had not moved above one mile in search of the foe when we fell in with them, attacked them instantly whilst they were attempting to form, dispersed them with some loss, and drove them for six miles, forcing them even through the very pickets of a numerous corps of militia commanded by General Sumner, who, supposing a large part of the army to be near at hand, broke up his camp and marched that evening sixteen miles.

From the enemy’s standpoint Major Joseph Graham has had one or two words to offer that would have been undoubtedly pleasing to Hanger’s ear:

The enemy seemed to understand this Parthian kind of warfare and maneuvered with great skill, the cavalry and infantry supporting each other alternately as the nature of the ground or opposition seemed to require. They taught us a lesson of the kind which in several instances was practised against them before the end of the war. During the whole day they committed nothing to hazard, except when the cavalry first charged up to the court house.

Returning at sunset to Charlotte, the Legion encamped across the street by which they had first entered the village. The rest of the troops encamped to the east, south-east and west of the court house. A veritable hornet’s nest of opposition was now stirred up, as Tarleton has made clear:

Charlotte town afforded some conveniencies blended with great disadvantages. The mills in its neighbourhood were supposed of sufficient consequence to render it for the present an eligible position, and in future a necessary post when the army advanced, but the aptness of its intermediate situation between Camden and Salisbury and the quantity of its mills did not counterbalance its defects. The town and environs abounded with inveterate enemies; the plantations in the neighbourhood were small and uncultivated; the roads narrow and crossed in every direction; and the whole face of the country covered with close and thick woods. In addition to these disadvantages no estimation could be made of the sentiments of half the inhabitants of North Carolina whilst the royal army remained at Charlotte town. It was evident, and it had been frequently mentioned to the King’s officers, that the counties of Mecklenburg and Rowan were more hostile to England than any others in America. The vigilance and animosity of these surrounding districts checked the exertions of the well affected and totally destroyed all communication between the King’s troops and the loyalists in the other parts of the province. No British commander could obtain any information in that position which would facilitate his designs or guide his future conduct.

The foraging parties were every day harassed by the inhabitants, who did not remain at home to receive payment for the produce of their plantations, but generally fired from covert places to annoy the British detachments. Ineffectual attempts were made upon convoys coming from Camden and the intermediate post at Blair’s Mill, but individuals with expresses were frequently murdered . . . Notwithstanding the different checks and losses sustained by the militia of the district, they continued their hostilities with unwearied perseverance, and the British troops were so effectually blockaded in their present position that very few out of a great number of messengers could reach Charlotte town in the beginning of October to give intelligence of Ferguson’s situation.

Matters were so bad that according to Charles Stedman, who was there, one half of the entire army one day, and the other the next, was needed to protect the foraging parties and cattle drivers. Hanger himself stated that the foraging parties were attacked by the enemy so frequently that it became necessary never to send a small detachment on that service:

Colonel Tarleton, just then recovered from a violent attack of the yellow fever, judged it necessary to go in person, with his whole corps or above two-thirds, when he had not detachments from the rest of the army. I will aver that when collecting forage I myself have seen situations near that town where the woods were so intricate and so thick with underwood (which is not common in the southern parts of America) that it was totally impossible to see our videttes or our sentries from the main body. In one instance particularly, where Lieutenant Oldfield[1] of the Quartermaster General’s Department was wounded, the enemy under cover of impervious thickets, impenetrable to any troops except those well acquainted with the private paths, approached so near to the whole line of the British infantry as to give them their fire before ever they were perceived. Charlotte town itself, on one side most particularly, where the light and Legion infantry camp lay, was enveloped with woods. Earl Cornwallis himself, visiting the pickets of these corps (which from Tarleton’s sickness I had the honour of commanding at that time) ordered me to advance them considerably further than usually is the custom and connect them more closely one with the other . . . As to the disposition of the inhabitants, they totally deserted the town on our approach. Not three or four men remained in the whole town.

When asked by a journalist what would throw his administration off course, the British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan replied, “Events, my dear boy, events.” It was now at Charlotte that unforeseen events conspired to terminate the autumn campaign.

The first of these was—as we have seen—the entirely unexpected ferocity with which the inhabitants of the locality continued resolutely to oppose the occupation of Charlotte itself. On October 3 Cornwallis commented to Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, the Commandant of Charlestown, “This County of Mecklenburg is the most rebellious and inveterate that I have met with in this country, not excepting any part of the Jerseys.” It soon became apparent that the village was completely unsuitable for a small intermediate post, so effectually would it have been blockaded and so high would have been the risk of its being taken out in detail. Preoccupied with defending itself, the post would have exerted no control over the surrounding territory and afforded no protection to messengers coming to and from Cornwallis as he pursued his onward march. Extraordinarily difficult as it already was to communicate with South Carolina (almost all of the messengers being waylaid), Cornwallis faced the prospect of totally losing his communication if he proceeded farther. He nevertheless contemplated advancing as late as the 11th, but as Rawdon explained to Balfour, the lack of communication with South Carolina brought about by the inveteracy of the Mecklenburg inhabitants, the uncertainty of cooperation with a diversionary force intended for the Chesapeake, and the possible consequences of a second event of calamitous proportions convinced him that he had to turn back. Abandoning the invasion, he quit Charlotte at sunset on the 14th.

The second event was the defeat of Major Patrick Ferguson and his loyalist militia. Instead of pressing ahead to join Cornwallis, he dallied and was overtaken on October 7 by revolutionary irregulars while posted on King’s Mountain near the north-west border of South Carolina. Ferguson was killed and his entire party consisting of the American Volunteers—a small British American corps—and some 800 militia was captured or killed.

Nothing is so certain as the unexpected, and it was the unexpected, magnifying the risks of losing territory to the south, that ultimately put paid to the northward invasion.

Bibliography

Davie, William Richardson, The Revolutionary War Sketches of William R. Davie, edited by Blackwell P. Robinson (Raleigh: North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1976).

Graham, Joseph, “Narrative”, in William Henry Hoyt ed., The Papers of Archibald D. Murphey(Raleigh: Publications of the North Carolina Historical Commission, 1914).

Hanger, George, An Address to the Army in reply to Strictures of Roderick M’Kenzie (late Lieutenant in the 71st Regiment) on Tarleton’s History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 (London, 1789).

Saberton, Ian, The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theatre of the American Revolutionary War, (Uckfield: The Naval & Military Press Ltd, 2010).

Saberton, Ian, George Hanger: The Life and Times of an Eccentric Nobleman (Tolworth: Grosvenor House Publishing Ltd., 2018).

Stedman, Charles, History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War(London, 1792).

Tarleton, Banastre, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America(London, 1787).

[1]A descendant of Sir Anthony Oldfield Bt, John Nicholls Oldfield (?-1793) was a Marine lieutenant and served with distinction on the staff of the Quartermaster General’s Department at Camden. He would resign his commission in 1789 and die on his small estate at Westbourne, Sussex, perhaps from the lingering effects of his wound. His only son John (1789-1863) would have a distinguished career in the Royal Engineers, rising to Colonel-Commandant with the rank of general, and being knighted for his services at the Battle of Waterloo and in the occupation of Paris (Oxford Dictionary of National Biography).

Recent Articles

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...