Even though American colonists protested the Stamp Act, the Declaratory Act, the Townshend Acts, the Boston Massacre and the Septennial Act, nothing pushed the colonies’ relationship with Britain to the point of no return more than the Boston Tea Party. It was premeditated, it destroyed private property, it violated the Tea Act, and customs officials were intimidated into moving to Castle Island.[1] Unknown at the time, the destruction of tea on the evening of December 16, 1773, began something that now could not be stopped.

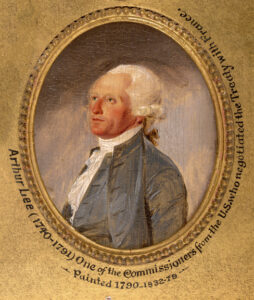

Arthur Lee, born December 20, 1740, was the youngest son of Thomas and Hannah Lee. At the time, the Lee family was one of the wealthiest families in Virginia. Arthur had three brothers, Richard Henry Lee, Francis ‘Lightfoot’ Lee and William Lee. The first two men would serve in the Virginia House of Burgesses and the Continental Congress and the third would serve as the Commissioner to the Court of Frederick the Great during the war. Arthur, however, had the broadest background. All of his education took place in Britain. When he was young, his father sent him to Eton College in England.[2] As soon as he completed his studies at Eton, his father enrolled him at the University of Edinburgh where in 1764 he graduated with a degree in medicine. Lee then returned to Virginia and opened a practice. After two years he lost interest in medicine. In 1766, he returned to London and began to study law at the Middle Temple. In 1770, he graduated with a degree in law and opened a practice for the next six years. In the same year, he was appointed Benjamin Franklin’s backup agent for the Colony of Massachusetts to the merchants of London and Parliament. During his ten years (1766-1775) in London, he became acquainted with a number of influential men in politics and commerce.

Many of his letters home were addressed either to his brothers or, surprisingly, to Samuel Adams; between December 1770 and July 1775 Lee and Adams exchanged fifty letters.[3] In his correspondence Lee showed his knowledge of what was occurring in the colonies as well as in Parliament, offered suggestions as to how to write any further appeals or remonstrances to Parliament or the King, and identified who in the Privy Council and Parliament could be trusted. What follows are two letters, the first addressed to Samuel Adams and the second most likely to Richard Henry Lee:

London, February 8, 1774

Dear Sir, I informed you in my last of the insolent abuse which the solicitor-general, Mr. Wedderburne, poured forth against Dr. Franklin before the privy-council, at the hearing of your petition.[4] Dr. Franklin bore it all with a firmness and equanimity which conscious integrity alone can inspire. The insult was offered to the people through their agent; and the indecent countenance given to the scurrilous solicitor by the members of the privy council, was at once a proof of the meanness and malignity of their resentment . . . .

I mentioned that they threatened to take away Dr. Franklin’s place. That threat they have now executed. The same cause which renders him obnoxious to them, must endear him to you. Among other means of turning their wickedness to their own confusion and loss, this of the post-office is not the least desirable, or most difficult . . . .

The present time is extremely critical with respect to the measures which this country will adopt relative to America. From the prevailing temper here, I think you ought to be prepared for the worst. It seems highly probable that an act of parliament will pass this session, enabling his majesty to appoint his council in your province. On Tuesday last the Earl of Buckinghamshire made a motion in the house of lords for an address to the king, to lay before them the communications from Gov. Hutchinson to the secretary of state.[5] He prefaced his motion with declaring, that these papers were to be required merely out of form; for that the insolent and outrageous conduct of that province was so notorious, that the house might well proceed to punishment without any farther information or enquiry. That it was no longer a question whether this country should make laws for America, but whether she should bear all manner of insults and receive laws from her colonies … One can hardly conceive a man’s uttering such an absurd rhapsody even in the delirium of a dream, much less in a deliberate, premeditated speech, and upon the most important question to this country that can ever come before the legislature. He was answered by the Earl of Stair, who said it could be consistent neither with humanity, justice, nor policy, to adopt the noble lord’s ideas against America. Lord Dartmouth then begged the motion might be withdrawn, not, as he said, from any desire to throw cold water on the noble lord’s zeal, but because the despatches were not yet arrived, and they would be laid before the house in due time. The motion was withdrawn . . . .

By very late letters from New-York we understand that it is settled to return the tea, as at Philadelphia; and that the governor will not interfere. This completes the history of that unfortunate adventure; but it leaves Boston singled out as the place where the most violence has been offered to it. Your enemies here will not fail to take advantage of it, and Mr. Hutchinson’s representations I presume will not soften the matter. They will shut their eyes to what is obvious, that his refusal to let it repass the fort compelled you to that extremity. Be prepared therefore to meet some particular stroke of revenge during this session of parliament; and instead of thinking to prevent it, contrive the means of frustrating its effect. I have already mentioned the alterations of your charter relative to the election of the council; but I am in hopes true patriotism is too prevalent and deep-rooted among you, to suffer them to find twelve men even upon the new establishment abandoned enough to betray their country.[6]

London, March 18, 1774

Dear Brother, The affairs of America are now become very serious; the minority are determined to put your spirit to the proof. Boston is their first object. On Monday the 14th, it was ordered in the house of commons that leave be given to bring in a bill, ‘for the immediate removal of the officers concerned in the collection and management of his majesty’s duties of customs from the town of Boston, in the province of Massachusetts Bay, in North America; and to discontinue the landing and discharging, lading and shipping of goods, wares and merchandize at the said town of Boston, or within the harbour thereof.’

If the colonies in general permit this to pass unnoticed, a precedent will be established for humbling them by degrees, until all opposition to arbitrary power is subdued. The manner, however, in which you should meet this violent act, should be well weighed. The proceedings of the colonies, in consequence of it, will be read and regarded as manifestos. Great care therefore should be taken to word them unexceptionably and plausibly. They should be prefaced with the strongest professions of respect and attachment to this country; of reluctance to enter into any dispute with her; of the readiness you have always shown and still wish to show, of contributing according to your ability and in a constitutional way to her support; and of your determination to undergo every extremity rather than submit to be enslaved. These things tell much in your favor with moderate men, and with Europe, to whose interposition America may yet owe her salvation, should the contest be serious and lasting. In short, as we are the weaker, it becomes us to be suaviter in modo,[7] however we may be determined to act fortiter in re.[8] There is a persuasion here that America will see, without interposition, the ruin of Boston. It is of the last importance to the general cause, that your conduct should prove this opinion erroneous. If once it is perceived that you may be attacked and destroyed by piecemeal … every part will in its turn feel the vengeance which it would not unite to repel, and a general slavery or ruin must ensue. The colonies should never forget Lord North’s Declaration in the house of commons, that he would not listen to the complaints of America until she was at his feet. The character of Lord North, and the consideration of what surprising things he has effected towards enslaving his own country, makes me, I own, tremble for ours. Plausible, deep and treacherous, like his master he has no passions to divert him, no pursuit of pleasure to withdraw him from the accursed design of deliberately destroying the liberties of his country. A prefect adept in the arts of corruption, and indefatigable in the application of them, he effects great ends by means almost magical, because they are unseen. In four years [9] he was overcome the most formidable opposition in this country, from which the Duke of Grafton fled with horror. At the same time he has effectually enslaved the East India Company, and made the vast revenue and territory of India in effect a royal patronage. Flushed with these successes, he now attacks America; and certainly if we are not firm and united, he will triumph in the same manner over us. In my opinion a general resolution of the colonies to break off all commercial intercourse with this country, until they are secured in their liberties, is the only advisable and sure mode of defense. To execute such a resolution would be irksome at first, but you would be amply repaid, not only in saving your money, and becoming independent of the petty tyrants, the merchants, but in securing your general liberties . . . .[10]

The primary position of Arthur Lee in all of his letters is best represented in letter dated December 22, 1773:

Believe me sir, the harmony and concurrence of the colonies is of a thousand times more importan[t] in this dispute than the friendship or patronage of any great man in England. The heart of the king is hardened like that of Pharoah against us. His noble are so servile that they will not attempt any thing to which he is averse, unless necessity should compel both him and them to assume a virtue which they do not possess. That necessity must come from your general, firm, permanent opposition. To cultivate and preserve that, is therefore the first object of American policy[11]

The insights and the information that Arthur Lee was able to send back to the Continental Congress cannot be measured. Frequently what he learned was included in a letter and on board a ship for Philadelphia within twenty-four to forty-eight hours after he had secured it. The individuals he had access to ran from ships’ captains to merchants to men in coffee-shops to members of Parliament to printers to court officials. As a source of political, diplomatic and commercial information from London, for ten years Lee was second only to Benjamin Franklin.

[1] “The who[le] Affair was conducted with the greatest dispatch, Regularity & Management, so as to evidence that there were People of Sense & of more discernment than the Vulgar among the Actors.” Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011), 132.

[2] At the time considered the best grammar school in England.

[3] Samuel Adams and Harry Alonzo Cushing, The Writings of Samuel Adams (Salt Lake City, UT: Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, 2000), Volumes 1, 2 and 3. Arthur Lee was encouraged to befriend Adams by Stephen Sayre, a friend. He wrote to Adams on January 10, 1770 and introduced himself. After conveying his respect for Adams’ steadfastness and commitment to liberty, he hoped that Adams would consider being his information source on what was transpiring in Boston:

I observe that those who write in the public papers here against your town, are furnished with very speedy and accurate intelligence on all political affairs with you, which they communicate in such portions and manner as may best prejudice the public and promote their purposes. I have often lamented the want of authentic information to refute them, where from the general complexion of their story I conjectured it was fraudulent and false. It will not, however do to hazard one’s conjecture on this ground, because being once wrong would fix mistrust on every future attempt. I shall therefore be always obliged to you for such intelligence as will enable me to detect their falsehoods, and defend the province and the town from their unjust aspersions. [Richard Henry Lee, Life of Arthur Lee, LL. D. (Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1829), 1:250-51]

[4] The petition from the Massachusetts House of Representatives for the removal of Gov. Thomas Hutchinson and Lt. Gov. Thomas Oliver.

[5] The Secretary-of-State for the Colonies was William Legge, the Earl of Dartmouth.

[6] Richard Henry Lee, Arthur Lee, LL. D. (Boston: Wells and Lilly, 1829), 1:240-42.

[7] “Pleasantly in manner.”

[8] “Powerfully in deed.”

[9] Lord North became the Prime Minister of England on January 28, 1770.

[10] Lee, Life of Arthur Lee, 1:207-09.

[11] Arthur Lee to Samuel Adams, December 22, 1773, ibid., 1:239.

Recent Articles

The New Dominion: The Land Lotteries

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

A Strategist in Waiting: Nathanael Greene at the Catawba River, February 1, 1781

Recent Comments

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...

"Ebenezer Smith Platt: An..."

Sadly, no

"Comte d’Estaing’s Georgia Land..."

The locations of the d'Estaing lands are shown in Daniel N. Crumpton's...