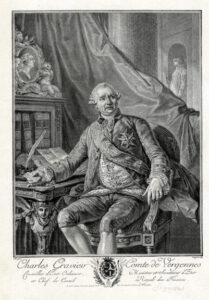

Historians generally agree on who were America’s principal Founders, but the roll call invariably omits the name of one individual without whose steadfast assistance the United States would have been unlikely to have gained independence. Comte Charles Gravier de Vergennes, France’s foreign minister throughout the long, desperate war, was a crucial player in America’s victory and realization of independence.

France had suffered a devastating defeat in 1763 at the hands of Great Britain in the Seven Years’ War. The French navy had been laid waste and France lost Nova Scotia, Acadia, Quebec, all the territory it had claimed east of the Mississippi River, some West Indian colonies, its commanding share of the Newfoundland fisheries, and Senegal and assorted African slave-trading posts. Spain, France’s Bourbon ally, also sustained shocking losses in the peace settlement of 1763. Both countries soon began rebuilding their navies, aiming to eventually possess numerical superiority, but it was a time-consuming process that could not be achieved overnight.[1]

France’s long-term goals were redemption and retaliation against Great Britain. As it was axiomatic at Versailles that British hegemony stemmed from the wealth it derived from its colonial possessions in America, France twice dispatched secret agents to the colonies after 1765 when protests erupted against Britain’s new colonial policies. The operatives were to determine if the uprisings might lead to war. The agents reported that as the colonists did not possess the capability to respond with force, a revolutionary war was not imminent.[2]

By 1774 the situation in America had changed and Comte de Vergennes, the scion of a noble family in Dijon, had become France’s foreign minister. In June, the fifty-four year old Vergennes was serving as ambassador to Sweden when the new king, twenty-one year old Louis XVI, summoned him to take the reins as foreign minister. Writing to Vergennes of the “good that I hear spoken of you from all sides,” the monarch asked him to come quickly to Versailles.[3]

Vergennes took office as the long-simmering tensions between America and Britain reached a crescendo. In September, the First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia to determine whether to submit or defy the imperial authorities. Congress chose defiance and within Vergennes’ first year in office the Revolutionary War began.

Louis XVI emphasized his wish to avoid war. Vergennes also sought to avoid hostilities, at least until the navy’s rehabilitation was complete, likely around 1778. That did not constrain him from taking risks. Vergennes’ cherished goal was the restoration of French power and prestige, and he understood that the Anglo-American war might be a heaven-sent opportunity to fatally diminish Britain’s strength. Convinced that Britain would be seriously, possibly fatally, weakened should it lose its American colonies, Vergennes contemplated aiding the rebels. First, however, he required a better understanding of the rebellion. In the fall of 1775, Vergennes sent Achard de Bonvouloir, a French army officer, to Philadelphia to assess the mood in America and Congress. Bonvouloir arrived near the end of the year and met covertly in Carpenter’s Hall with Congress’s Secret Committee. The committee members asked if France would sell military supplies to the Americans and also provide two capable army engineers. Bonvouloir promised to pass along the requests to the foreign ministry. He also advised Congress not to send an envoy to France. Should Britain learn that a congressional emissary was in Paris, he cautioned, France might decline to send assistance. Congress ignored his advice and dispatched Silas Deane with instructions to request arms and ammunition for an army of 20,000, as well as one hundred pieces of artillery.[4]

Bonvouloir’s sanguine report reached Vergennes in February 1776. The envoy divulged that the Continental army was well-led, the colonies teemed with militiamen, and the congressmen were prepared “to fight to the end for their freedom.” Britain would “have to chop them to bits” to win the war, he added. Bonvouloir also disclosed that the rebels lacked every sort of provision required for a military force. Convinced that it was now or never if France was to benefit from Britain’s American troubles, Vergennes moved quickly. After gaining Spain’s assurance that it was willing to aid the American rebels, he sought the approval of the Conseil de Roi, the king’s advisory council, for aiding the Americans.[5]

The monarch was wary of supporting a republican insurrection and some members of the council opposed aiding the Americans. The most substantial resistance was offered by Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, the recently appointed Comptroller-General. Turgot argued that French assistance was unnecessary as Britain could never crush the colonial insurgency. He also feared that French meddling would result in a catastrophic war with London that “will drive the state to bankruptcy.”[6]

Vergennes countered with two memoirs, “Considerations” and “Reflections.” Aid to the Americans would be “cloaked and hidden” so as not to provoke the British, he advised. He added that if the Americans gained independence, Britain would be severely weakened, France could gain much of the American trade, and French national security would be enhanced. Vergennes had outlined a plan for a proxy war. The Americans would do the fighting and dying to gain their objectives and eventually France would reap handsome rewards from the faraway war. In May 1776, Louis XVI sided with Vergennes and approved an appropriation of one million livres in assistance to the Americans.[7]

Vergennes turned to Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a commoner who had become France’s best known playwright following his hit “The Barber of Seville,” for the monumental task of acquiring weaponry and other military paraphernalia and getting it to the Americans. Beaumarchais had lobbied for the assignment, confident that he could make a tidy profit by trading French goods for American tobacco and other articles. Though not a businessman, he resolutely declared that his zeal would overcome his inexperience in commerce. Beaumarchais created a company, Roderique Hortalez et Compagne, and set to work on the months-long job of obtaining the materials and getting them to ports for shipment. As Amphitrite, the first ship laden with goods for the Continental army, would not sail until December, the Americans were on their own in the campaign of 1776.[8]

It was not a good year militarily for the Americans. Defeat followed defeat in Canada and New York, bringing on what Thomas Paine ever afterward called the “dark period” of the Revolutionary War. Some congressmen anguished that the war was lost and, in December, an onlooker described Gen. George Washington’s army as “dirty, ragged, badly clothed, badly disciplined and badly armed.” Washington himself lamented that “affairs are in a very bad way” and the “game is pretty much up.”[9]

The dark clouds lifted somewhat in December and January 1777 following Washington’s spectacular victories at Trenton and Princeton, and again in March when the first two of Beaumarchais’ vessels, Mercure and Amphitrite, arrived in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Washington was informed that the French ships were “deeply laden” with muskets, mostly in “very fine” condition, as well as gunpowder, uniforms, blankets, and shoes. Six additional French vessels packed with arms and clothing to outfit an army of 30,000 would be coming. By June, 200 pieces of French artillery, 30,000 light flintlock muskets, and thousands of bayonets and tents had arrived. Flints, lead for shot, and blankets sent by Spain had also arrived.[10]

Vergennes did not foresee an immediate end to the Anglo-American war. He envisaged a war lasting two or more years. He hoped that the better-armed and provisioned Americans would thwart Britain’s armies, causing London to eventually see the futility of continuing to fight. In 1777, Vergennes worried less about Britain scoring a decisive victory than the possibility that the war would deadlock, leading the weary rebels to accept a negotiated settlement through which they would remain in the British Empire.

That was not Vergennes’ only worry in 1777. The arms shipments, as well as the departure of the Marquis de Lafayette and other volunteers to assist the American rebels, had been provocative steps, and Vergennes was anxious that Britain might retaliate by going to war with France. By mid-year, he was confident that Britain would not strike back. However, as he knew that the reclamation of the French navy would not be completed for several months, Vergennes understood that France must avoid additional inflammatory acts that might draw Britain into the war. He refused the request of American diplomats – Deane, Benjamin Franklin, and Arthur Lee – for a commercial accord. Nor would he tolerate American privateers selling their prizes, cargoes seized from captured British merchant ships, in French ports. All the while, he anxiously awaited word of the outcome of the fighting in America in 1777, where a British army under Gen. John Burgoyne had invaded New York and another under Gen. William Howe was targeting Philadelphia.[11]

It is possible, even probable, that Vergennes always suspected that the American rebels could not achieve independence with covert Bourbon assistance and that someday France would have to enter the war. During 1777 he engaged in lengthy discussions with Spain’s foreign minister, Conde de Floridablanca, about the two nations going to war with Britain in 1778. The “time has come to decide” whether to “abandon America to its own devices or . . . effectively come to its side,” Vergennes declared. Floridablanca replied that Spain would not be ready for war in 1778. Vergennes was prepared to come to the rebels’ side, but he was not about to engage in a losing cause. He waited for word on the outcome of the 1777 campaign.[12]

It arrived in December when Franklin learned from a relative in Boston that “God be prased . . . General Burgoyne and his Whol Armey [are] Prisoners of War” at Saratoga. The tidings allegedly made Franklin weep with joy. He and his colleagues wasted no time in notifying Vergennes. The news, they said, “occasion’d as much general Joy … as if it had been a Victory of their own Troops over their own Enemies.” Washington was not as successful in defending Philadelphia but, according to Congress, he emerged from the campaign in command of “a good army.”[13] Vergennes was profoundly impressed by word of Washington’s surprise attack on Howe’s army at Germantown outside of Philadelphia. Although the strike failed, Vergennes was stirred by the American commander’s vigor and boldness. John Adams, who was in Paris, was told that Washington’s daring assault was pivotal in convincing the French that “America would finally succeed.”[14] To this point, Vergennes appears to have thought that if France someday opted to enter the war, it would be because the Americans were too weak to fend for themselves any longer. Suddenly, the Americans had never seemed stronger. An entire British army had been vanquished and the Continental army, led by a daring commander, had survived the campaign of 1777. Convinced “of the ability and resolution of the states to maintain their independency,” and presciently apprehensive that Britain would now offer the colonists favorable terms for reconciliation, Vergennes directed his secretary to ask the American envoys to request an alliance.[15]

Before taking that step, Vergennes required the monarch’s approval for entering into hostilities, as allying with the colonists assuredly meant war. He also hoped the king would consent to the dispatch of a large naval squadron that might destroy the Royal Navy’s fleet in American waters. In mid-summer, the Conseil de Roi had preliminarily committed to war, though it deferred a final decision until it learned the outcome of the 1777 campaign. Some council members had opposed going to war, largely from fear that it would be economically catastrophic. Following word of Saratoga, Vergennes countered with arguments that supported French belligerence. He maintained that the rebels would be a dependable ally and hostilities would not be protracted. As Britain would face two adversaries, Vergennes contended that it would be more vulnerable than ever. He also stressed that the Americans could not win independence unless France came into the war. The moment to act had arrived, he told the king’s advisors. If France did not enter the war, Britain and its colonies would reconcile, a step that would restore and preserve British power. Simultaneously, Vergennes made one last stab at bringing Spain into the fray. Louis XVI and his counselors approved an alliance and the commitment of a naval task force. Spain declined to enter the war and advised that it would remain neutral in 1778.[16]

Negotiations with the American envoys proceeded rapidly. In February, a month after the talks began, the French and Americans signed two accords, a Treaty of Amity and Commerce and a Treaty of Alliance. In the Treaty of Alliance, the two countries pledged not to make a separate peace with Britain and to remain at war until Britain recognized American independence. France forswore “forever the possession” of Canada and the United States was to retain whatever additional possessions “or conquests that their Confederation may obtain during the War.” A few days after the treaties were signed the American envoys were introduced to Louis XVI as the “ambassadors of the Thirteen United Provinces.” Vergennes lauded their “wisest, most reserved conduct,” but the alliance with France was largely the result of the American victory at Saratoga, the survival of the Continental army through three distressing years of war, and the completion of France’s naval rearmament at just the right time. Nothing was more crucial than Saratoga, a triumph that in all likelihood could never have been achieved without the arms sent earlier in the year by France. Caleb Stark, who soldiered in a New Hampshire regiment and was wounded at the Battle of Bemis Heights in October 1777, was spot on in his assertion that had it not been for what he called “the Beaumarchais arms,” Burgoyne would have made “an easy march to Albany.”[17]

Washington was ecstatic at news of the alliance. He exclaimed that events were “verging fast to one of the most important periods that America ever saw.” French belligerency would drive away the “dark and tempestuous Clouds which at times appeared ready to overwhelm us,” he said, adding that it would give “a most happy tone to all our affairs.” Washington exuberantly predicted that the alliance would “chalk out a plain and easy road to independence” and put “the Independency of America out of all manner of dispute.”[18]

Washington’s buoyance was misplaced. A French naval squadron consisting of twelve ships of the line and five frigates arrived in June 1778, but during the next two years the fleet accomplished nothing beyond taking a couple British islands in the Caribbean. Commanded by Charles-Hector Théodat, Vice Adm. Comte d’Estaing, the fleet found New York’s harbor too shallow to enter. Versailles’ expectation that the Royal Navy’s smaller fleet would be surprised and destroyed was foiled. D’Estaing next sought the destruction of the British army in Newport, but in August that endeavor failed as well due to an abundance of mistakes and ill fortune. Late in 1778, d’Estaing sailed to the West Indies to see to French interests in that theater. Another year of war had ended inconclusively and during the year the American economy collapsed and morale on the home front showed unmistakable signs of fatigue. Washington now asked: “Can we carry on the War much longer?” He answered, “certainly No.” Lamenting that the struggle was trying “the patience, fortitude & virtue of Men,” Washington sensed that Britain would do what it could to prolong the war. He anticipated that his adversary would seek to extend hostilities until, in time, morale was so eroded that Americans were willing to accept British peace terms short of independence.[19]

Given the promise of French naval superiority, Vergennes had also expected success in 1778. Instead, the war stalemated with no end in sight. Victory, he was compelled to acknowledge to Louis XVI, hinged on the “combined operations” of the Bourbon powers. He confessed that Madrid’s price for entering hostilities would be “gigantic,” but their terms must be met. The monarch consented and in April 1779 France and Spain concluded the Treaty of Aranjuez. Spain would enter the war to acquire Gibraltar, Florida, Minorca, and to drive the British out of Campeche, modern Belize, Honduras, and Guatemala. Spain demanded a joint invasion of England, as it was convinced that taking control of territory in England was the only means of prying Gibraltar from Britain. Vergennes reluctantly met what he regarded as Spain’s extortionate terms.[20]

Spanish belligerency did not lead to rapid victory. Indeed, Vergennes found 1779 to be as disappointing as the previous year. The projected invasion of England failed due to disease and miscalculations. Shortly thereafter, Admiral d’Estaing returned from the Caribbean and in October attempted to liberate Savannah, which the British had taken in 1778. But a siege operation failed and an attack by Allied troops was repulsed with heavy losses. Washington spoke of the “Disaster at Savannah,” while Gen. Henry Clinton, commander of the British army in America, rejoiced that d’Estaing’s failure was “the greatest event that has happened in the whole war.” Just as Washington had earlier envisioned, Clinton saw time as his ally. Washington knew that it was his enemy. Washington despaired that “difficulties surround us on every side” and added that America’s “prospect is gloomy.” Confiding that he had “almost ceased to hope” that independence could be achieved, Washington in the wake of the barren campaign of 1779 understood that America’s success hinged on French perseverance.[21]

Vergennes persevered, although he had come to feel betrayed by Washington. In private, he asserted that whereas Washington’s conduct had been distinguished by “spirit and enterprize” prior to the alliance, he had exhibited nothing but “inactivity” thereafter. Knowing that Lafayette would pass along his observations to Washington, Vergennes wrote to him of his displeasure with the Americans’ “lack of zeal.” He warned that if the American army did not “put more vigor into their conduct,” he would have to conclude that they now had “but a feeble attachment” to securing independence.[22]

Vergennes was troubled by more than Washington’s alleged inertia. Concern over France’s tenuous economic situation had grown as the nation’s indebtedness and military expenditures steadily mounted. Jacques Necker, who had succeeded Turgot in 1777, warned of the political, economic, and social perils caused by the war. Some at Versailles pushed for ending the war through a negotiated settlement. Others, who wished to continue, stressed that France’s military ends could best be attained in Europe, not in America, and particularly by acting in concert with Spain against British-held Gibraltar. If all this wasn’t sufficiently vexing, Vergennes was aware that Necker was putting out peace feelers to men of influence in England and Spain was engaged in supposedly secret talks with British intermediaries.[23]

Through it all, Louis XVI continued to think the war could be won and that the prizes that might come with victory were too alluring to be cast aside just yet. Vergennes advised that the best chance of victory was in North America, not in Europe, but he and others conceded that strategic changes were necessary. Secret aid and d’Estaing’s large fleet had been insufficient to gain French ends. Inexorably, talk centered on the need to send an army, a proposal made by Lafayette among others. Lafayette provided sound counsel to Vergennes, assuring him that Washington could be depended on, but warning that the Continental army was on its last leg. He urged that France send 15,000 muskets and tons of powder to the Americans, as well as an army of 4,000. Not surprisingly, the twenty-two year old Lafayette also proposed that he be given command of the army.[24] The issue percolated for weeks and was finally resolved early in 1780. France committed to sending an army of 7,500 under Lt. Gen. Jean-Baptiste-Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau – who had become a general officer before Lafayette’s birth – and a naval squadron roughly half the size that d’Estaing had commanded. Problems arose at the port of embarkation and the fleet sailed with 4,000 men and a promise that the remainder would depart later. Before Rochambeau’s army arrived in July 1780, Vergennes emphasized to Lafayette that the Franco-American armies were to “effectually” cooperate in the operations he expected.[25]

Rochambeau and Washington met at Hartford, Connecticut in September. The French commander refused to act until the remainder of his army arrived, but he and Washington agreed that the campaign of 1781 would center on retaking New York. Meanwhile, the Americans suffered a series of disasters. Clinton took Charlestown, South Carolina, in May—which Vergennes said provoked keen “astonishment” at Versailles—and the British destroyed an American army at Camden, South Carolina, in August. In the eighteen months between December 1778 and the summer of 1780, the Allies had suffered 10,000 wounded and killed in military engagements in the South. In September, Benedict Arnold committed treason, an act that a shocked Vergennes labeled as an “abominable” and “infamous” crime. As 1780 wound down, Washington deplored the sense of despair that was creeping into the corners of the country. A South Carolina congressman declared that after Camden the “Spirit to oppose the Enemy” had vanished within his state. Even in lionhearted Massachusetts some officials were heard to say that a peace settlement short of American independence was inevitable. In the midst of these crumbling spirits, Washington could only lament that the Allied armies had been “compelled to make an inactive campaign” while the enemy was “preparing to push us in our enfeebled state.”[26]

At the dawn of 1781, Vergennes was awash with problems. Another year had gone by without an Allied victory, Washington and Rochambeau had not taken the field against the British army, Floridablanca was still talking with the British, the French economy remained acutely troubled, and Europe’s neutral nations—led by Russia and Austria—were calling for mediation through an international conference to end the war. Vergennes wanted one more year to seek a decisive victory, although he privately acknowledged his willingness to end hostilities in America on terms of uti possidetis, each belligerent keeping what it possessed at the moment the guns fell silent. Vergennes thought Britain must relinquish New York, but otherwise London would be left in possession of much of the western territory above the Ohio River, the northern reaches of Maine and Vermont, Georgia, much or all of South Carolina, East Florida, and possibly North Carolina. An independent United States would possess the scraps that were left east of the Appalachians. The contemplated international conference to end the war in 1781 never met and an agreement to end the war through a settlement based on uti possidetis never materialized, in large measure because Spain and Britain were unwilling to lay down their arms. Spain wished to continue fighting in hopes of gaining Gibraltar. Britain gambled that it could recover more of what it had possessed or claimed prior to the war. After consulting John Adams, whom Congress had appointed to negotiate peace when that day came, Vergennes advised Russia and Austria that mediation was off the table due to American objections.[27]

Vergennes weathered the peace storm and, in fact, crucial decisions by the Conseil du Roi soon followed that gave the foreign minister renewed hope for the coming campaign in 1781. Although it was decided not to send the promised second division to General Rochambeau, Louis XVI committed to a gift of six million livres to the United States and agreed to dispatch a squadron of twenty ships of the line across the Atlantic. The armada would include more than 3,000 marines and it was assumed the fleet commander might pick up additional ships in the Caribbean to go with the eight in Newport. In January, the naval department chose François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, to command the task force and promoted him to rear admiral. His instructions were to sail to the Caribbean, but with Spanish approval he was to proceed to North America late in the summer. The instructions said nothing about his destination in North America. At the same moment, Vergennes yet again urged that “vigorous measures” be taken in 1781 by the Allied armies in America.[28]

De Grasse, in August 1781, sailed to Chesapeake Bay, where a British army of some 7,500 men under Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis was posted at Yorktown on the York River. On September 5, in the Battle of the Virginia Capes, de Grasse repulsed a British fleet under Rear Adm. Thomas Graves, who had been sent from New York to drive away the French squadron. Cornwallis’s army was trapped and Graves’ severely damaged fleet could not be repaired in time to attempt to rescue the snared soldiers. Once the Allied forces gathered in October – 8,600 French troops, 8,280 Continentals, and 5,535 American militiamen – Cornwallis’s army was doomed. He surrendered on October 19, 1781, six and a half years to the day since the war began at Lexington and Concord. The evisceration of Cornwallis’s force was the elusive decisive victory that Vergennes had for years anticipated, and in due course it led to peace negotiations and the recognition of American independence.

Vergennes had sought American independence, though he preferred that the new American nation be small and largely surrounded by British-held territory, rendering the United States a client state – a dependency – of France. But he did not intrude on the peace negotiations conducted by the American envoys in 1782, and in the Treaty of Paris the United States gained its independence and nearly all of the transmontane West, a bounty that held the promise of enabling the new nation to one day be powerful, secure, and truly independent.

Like America’s principal Founders, Vergennes had sought American independence since 1776, though he was driven by the belief that America’s escape from the British Empire would be in the interest of France. Also like America’s Founders, Vergennes ran considerable risks to enable the colonists to break free of British control. In the course of his unwavering support, he played an instrumental role in providing secret assistance to the colonists, allying with the United States, sending a fleet to assist it in winning the war, and ultimately in dispatching Rochambeau’s army and Admiral de Grasse’s naval squadron. It is doubtful that the American rebellion could have survived beyond 1777 without French assistance and virtually certain that independence could not have been won without the helping hand provided by France. Vergennes is never likely to be seen as a Founder alongside Washington, Franklin, Adams, Jefferson and others, but as one who played an instrumental role in sustaining the American war effort and the achievement of American independence, perhaps he is due a ghostly presence in the ranks of America’s Founders.

[1] Jonathan R. Dull, The French Navy and American Independence: A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774-1787 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1975), 8-12, 16-19.

[2] Edward S. Corwin, French Policy and the American Alliance of 1778 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1970), 40-44.

[3] Orville T. Murphy, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes: French Diplomacy in the Age of Revolution, 1719-1787 (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1982), 14-207.

[4] Orville T. Murphy, “The View from Versailles: Charles Gravier Comte de Vergennes’s Perceptions of the American Revolution,” Diplomacy and Revolution: The Franco-American Alliance of 1778, eds. Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1981), 107-30; Committee of Secret Correspondence Minutes of Proceedings, March 2, 1776, Paul H. Smith, ed., Letters of Delegates to Congress, 1774-1789 (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1976-2000), 3:320-22 (LDC); Robert Morris to Silas Deane, April 4, 1776, ibid., 3:489.

[5] Larrie D. Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016), 53-54; Leonard W. Labaree, et al., eds., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1959 – ), 22:310-18 (PBF).

[6] Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 44-48.

[7] Jonathan R. Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 57-61; Henri Doniol, ed., Histoire de la participation de la France `a l’éstablissement des États-Unis d’Amérique (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1886-99); Benjamin F. Stevens, ed., Facsimiles of Manuscripts in European Archives Relating to America, 1773-1783 (New York: AMS Press, 1889-1898), 13: no. 1316.

[8] Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais to Louis XVI, September 21, 1775, Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris, eds., The Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants (Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merrill, 1958), 1:245-46; Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms, 47-49, 52, 54-61.

[9] John Adams to Abigail Adams, April 28, 1776, L. H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Family Correspondence (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963 – ), 1:399-400; Adams to Samuel Parsons, August 19, 1776, L. H. Butterfield, ed., Adams Diary and Autobiography (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1961), 3:449; Samuel Adams to Joseph Warren, November 29, December 25, 1776, LDC, 5:552, 661; William Gordon, The History of the Rise, Progress, and Establishment of the Independence of the United States of America (New York: Hodge, Allen, and Campbell, 1789), 2:354; The Journal of Nicholas Cresswell, 1774-1777 (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1968), 163-64; George Washington to John Augustine Washington, November 6 [-19], 1776, Philander Chase, et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington: Revolutionary War Series (Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1985 – ), 7:105 (PGW); Washington to Lund Washington, December 10 [-17], 1776, ibid., 7:370-71.

[10] Joseph Reed to Washington, February 13, 1777, PGW, 8:328; Nathanael Greene to Washington, March 24, 1777, ibid., 8:628, 628n; William Whipple to John Langdon, January 3, 1777, LDC, 6:29; Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms, 61-63; Thomas F. Chávez, Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift (Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), 49; American Commissioners to the Committee of Secret Correspondence, March 12 [-April 9], 1777, PBF, 23:467.

[11] American Commissions to the Committee of Secret Correspondence, December 8[-10], 1776, January 4, 1777, PBF, 23:30-31, 113-14; editor’s note, ibid., 24:322-23; Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution, 77-81.

[12]Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms, 95.

[13] Jonathan Williams, Sr. to Franklin, October 25, 1777, PBF, 25:113; The Committee for Foreign Affairs to the American Commissioners, October 31, 1777, ibid., 25:134; The American Commissioners to Vergennes, December 4, 8, 1777, ibid., 25:236, 260-61; American Commissioners to the Committee for Foreign Affairs, December 18, 1777, ibid., 25:305.

[14] John Adams to James Lovell, July 26, 1778, Robert J. Taylor, et al., eds., The Papers of John Adams (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977 – ), 6:318-19.

[15]Conrad-Alexandre Gérard to the American Commissioners, December 5, 1777, PBF, 25:246; editor’s note, ibid., 15:246.

[16] Munro Price, Preserving the Monarchy: The comte de Vergennes, 1774-1787 (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 49-50; Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 84-94.

[17] Franklin and Silas Deane to the President of Congress, February 8, 1778, PBF, 25:634-35; Caleb Stark, Memoir and Official Correspondence of Gen. John Stark, With Notices of Several Other Offices of the Revolution (Boston: Gregg Press, 1972), 351, 357. The two treaties are printed in PBF, 25:585-626.

[18] Washington to Richard Henry Lee, May 25, 1778, PGW, 15:216-17; Washington to Nicholas Cooke, May 26, 1778, ibid., 15:223; Washington to John Augustine Washington, May [?], 1778, ibid., 15:285-86; Washington to Robert Morris, May 25, 1778, ibid., 15:221.

[19] Washington to Gouverneur Morris, October 4, 1778, ibid., 17:253; 20:385; Washington to Andrew Lewis, October 15, 1778, ibid., 17:388; Washington to William Fitzhugh, April 10, 1779, ibid., 20:31.

[20] Chávez, Spain and the Independence of the United States, 127-28; Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms, 114-15; Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 142-43; Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution, 107-9; Murphy, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, 261-77.

[21] David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775-1780 (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 135-92; Washington to Philip Schuyler, November 24, 1779, PGW, 23:421; Washington to Laurens, November 5, 1779, ibid., 23:159; Washington to Friedrich Steuben, April 2, 1780, ibid., 25:288-89; Washington to Continental Congress Committee on Reducing the Army, January 28, 1780, ibid., 24:224; Washington to Joseph Reed, May 28, 1780, ibid., 26:221; Henry Clinton to William Eden, November 19, 1779, Stevens, Facsimiles of Manuscripts in European Archives Relating to America, 10, no. 1032.

[22] Vergennes to Marquis de Lafayette, August 7, 1780, Stanley Idzerda, et al., eds. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1976-1983), 3:129; Murphy, “The View from Versailles,” in Hoffman and Albert, Diplomacy and Revolution, 140-41.

[23] Price, Preserving the Monarchy, 51-52; Richard B. Morris, The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 14, 52, 89-93; H. M. Scott, British Foreign Policy in the Age of the American Revolution (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1990), 313-14.

[24] Lafayette to Jean Frédéric Maurepas, January 25, 1780, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 2:344-45; Lee Kennett, The French Forces in America, 1780-1783 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977), 8-10; Louis Gottschalk, Lafayette and the Close of the American Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942), 58-65.

[25] Kennett, The French Forces in America, 9-14; Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 187-88, 190; Vergennes, Instructions for Lafayette, March 5, 1780, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 2:366.

[26] Vergennes to Lafayette, August 7, 1780, December 1, 1780, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 3:129, 238; Washington to Franklin, December 20, 1780, PGW, 29:572; Washington to Samuel Huntington, December 15, 1780, ibid. 29:522; Aedanus Burke to Alexander Hamilton, April 1, 1790, Harold C. Syrett and Jacob E. Cooke, eds. The Papers of Alexander Hamilton (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961-1987), 6:336; Arthur Lee to Adams, September 18, 1780, Papers of John Adams, 10:185.

[27] Murphy, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, 330-31; Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 197-98; Price, Preserving the Monarchy, 52, 62; Samuel Flagg Bemis, The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (New York: Appleton-Century, 1935), 181-83; Dull, A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution, 130-31; Morris, The Peacemakers, 173-90; Austro-Russian Proposal for Anglo-American Peace Negotiations,” July 11, 1781, Papers of John Adams, 11:408-10; Adams to President of Congress, July 11, 14, 15, 1781, ibid., 11:410-11, 318, 419-20; Adams to Vergennes, July 7, 13, 16, 18, 19, 21, 1781, ibid., 11:405, 413-16, 420-22, 424-25, 425-29, 431-33; Adams, Memorandum, July 7, 1781, ibid., 11:405-6; Vergennes to Adams, July 18, 1781, ibid., 11:423-24.

[28] Murphy, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, 312-32; Ferreiro, Brothers at Arms, 235-36; E. James Ferguson, The Power of the Purse: A History of American Public Finance, 1776-1790 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1961), 126-27; Dull, The French Navy and American Independence, 216-21; Charles Lee Lewis, Admiral de Grasse and American Independence (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press,1945), 95-101; Lafayette to Nathanael Greene, April 4, 1781, Richard K. Showman, et al., eds., The Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1976-205), 52.

2 Comments

Early Vermonters agreed with you that Vergennes was a critical US founder! With the support of the infamous Ethan Allen, Michel Guillaume St. Jean de Crevecoeur (J. Hector St. John) successfully petitioned the Vermont legislature to name a city after Vergennes at the spectacular falls of Otter Creek in 1788. Additionally, Legislators were so appreciative of the Vermont naturalized Frenchman’s support that they named St. Johnsbury in his honor.

Wonderfully-informative article, Dr. Ferling. I learned a great deal from this and I consider myself a “fan” of the French Army and Rochambeau & Lafayette in particular. I can see now that the Comte de Vergennes’ contributions to the ultimate Patriot success have been under-valued.