Departing from Morristown, New Jersey, the Continental Army’s Maryland Division, Delaware Regiment, and 1st Continental artillery (approximately 1,400 men), were ordered south in April 1780 to break the siege of Charlestown and reinforce Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln’s beleaguered garrison. Upon reaching Petersburgh, Virginia, in early June, the surrender of Charlestown on May 12 became known. Despite this, Gen. George Washington authorized their commander, Maj. Gen. Baron Johann DeKalb, to continue his march south in order to support Southern militias and reestablish some semblance of the army’s Southern Department.

DeKalb’s command reached Hillsboro, North Carolina, on June 22 after a difficult march plagued with heat and a lack of provisions. Unable to sustain his army, DeKalb kept moving south, eventually reaching Cox’s Mill on Deep River (present day Randolph County, North Carolina) on July 19.[1]

During DeKalb’s march the Continental Congress on June 14 officially appointed Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates as commander of the Southern Department. Washington had preferred Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, but Gates, the Hero of Saratoga, was the popular choice—his reputation preceded him. A former British officer, he had served during the Seven Years War until being severely wounded at Fort Duquesne in 1755. Retired and living in Virginia at the start of the Revolution, he embraced the Patriot cause and served as the Continental army’s adjutant general where he earned a reputation as an able administrator.

Gates arrived at Cox’s Mill on July 25, relieved DeKalb of command and assumed leadership of the Southern Army. The following day he officially renamed the Southern Army the “Grand Army” and, wasting little time, ordered his new army to march into South Carolina on July 27.

Little did Gates know that the movement and actions of Patriot militia forces from July 23 through August 6 would determine the Grand Army’s fate. As the Grand Army prepared to march south from Cox’s Mill, two Patriot militia forces launched offensive operations within the Camden region—one in the east, a North Carolina militia army of 1,200 men commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard Caswell, and the other Brig. Gen. Thomas Sumter’s 600 mounted men in the west. While Caswell planned to push the British out of the Cheraw Hills and Pee Dee region; Sumter determined—after his unsuccessful attack on Rocky Mount July 30—that an all-out attack on Hanging Rock might trigger a British withdrawal from all their northern outposts.

General DeKalb and his officers considered a direct march to Camden logistically unsustainable, but General Caswell’s perception of the Pee Dee as “a plentiful Country” encouraged him to march south towards the Cheraw Hills. Unlike DeKalb, he was familiar with the region and the route to Camden, having marched his militia brigade through the area that May.[2]

Forcing Maj. Archibald McArthur’s 71st Highlanders to fight or abandon their Cheraw Hills outpost and occupy the Pee Dee region would strategically put Caswell’s militia “beyond the Scotch settlements of Cumberland, and thus interpose a strong patriot force between the hot-bed of Toryism and the line of British posts through South Carolina,” wrote historian John A. Moore in 1880.[3] Such thoughts may have influenced Caswell’s decision making.

But Caswell would not or could not wait for Gates to assume command of the regulars, let alone remain within supporting distance of the Grand Army. On July 23, two days before Gates arrived at Cox’s Mill, Caswell began his march down both sides of the Pee Dee River, scavenging and foraging all before it, leaving little subsistence for Gates’ Grand Army which followed on the 27th.

Gates had little option but to chase after Caswell’s militia army in an attempt to consolidate forces. Like DeKalb before him, Gates wrote several dispatches asking Caswell to countermarch or halt so his Continentals could link up, but Caswell—a former governor of North Carolina—kept marching, seemingly indifferent, preferring an independent command. Even so, his advance acted as a screening force for the Grand Army, albeit unintentionally. It also succeeded in finessing McArthur’s 71st Highlanders out of Cheraw Hills. As Caswell approached, the 71st dutifully fell back to Black Creek to await further orders.

Three Plans, One Attack

Lt. Col. Francis, Lord Rawdon ordered McArthur to assume a defensive position at Big Lynches Creek ferry and ordered the 33rd Regiment under Lt. Col. James Webster forward join them. He put his Volunteers of Ireland at Little Lynches Creek bridge with several pieces of artillery, prepared to support Webster or the Hanging Rock camp. He had never considered Camden defensible and determined a delaying action was preferable to falling back to defend the town.[4]

An examination of Rawdon’s situation August 5 reveals a viable if not tentative defensive perimeter within the Camden District. Lt. Col. George Turnbull’s New York Volunteers remained fortified at Rocky Mount; Bryan’s North Carolina Refugees, Royal North Carolinians, the Prince of Wales American Regiment, Legion infantry and others were established at Hanging Rock; the 23rd Welch Fusilier Regiment was in held in reserve at Rugeley’s Mill; and McArthur’s new defensive position at Big Lynches Creek seemed secure.[5]

That day, August 5, Sumter’s men were marching to attack Hanging Rock, and coincidentally Caswell planned to attack Rawdon’s troops defending at Big Lynches Creek. If launched, both American assaults—Hanging Rock and Big Lynches Creek—would take place on August 6. Were the attacks coordinated? Part of a greater strategy? No American source makes mention, although Rawdon, writing in 1801, did have his suspicions that Gates “waited the issue of an enterprize that was meditated against Hanging Rock.”[6]

Caswell plotted his surprise attack for early morning using information gleaned from a visitor who reported 700 British troops defending at the ferry.[7] Another surprise was that Rawdon planned to attack Caswell the same day! A Loyalist informant reported Caswell’s camp defenses were flawed and vulnerable. Did Patriot and Loyalist informants pass each other on the road? North Carolina’s Royal Governor-in-exile Josiah Martin, accompanying the British troops, remembered that Rawdon, “hearing that Caswell, with his Militia Corps, was within 13 Miles of us . . . determined to attack him that night or early in the morning.” However, a few hours later, Martin mentioned that Rawdon hurriedly aborted his attack when it was learned Gates’s army was encamped nearby.[8] Caswell too abandoned his plan upon receiving a new and exaggerated report that Rawdon intended to attack him with 2,900 men![9]

Unlike Caswell and Rawdon wrangling for advantage, Sumter attacked Hanging Rock as planned on the morning of August 6 with devastating effect. He sent a concise report to his friend and fellow South Carolinian Thomas Pinckney, one of Gates’s aides-de-camp:

The enemy had three large encampments in their Lines, so extensive that it was impossible to attack the Whole at once. In consequence of which I proceeded against the Most considerable of the Tory encampments and that of the British, which Lay in the Center, all upon exceeding advantageous hights. In about half an hour I had possession of Col. Bryant’s camp, the action Still Continuing very hot in the British, who were well posted, and had the advantage of a field-piece and open ground all around them. They had Detached a Colum to support Bryant, who, through a swamp, found means to turn my Right flank. The action was again Renewed upon that quarter. At length every man of them was either Kild or taken. The British camp was then attacked with greater violence and They sustained it with Great Bravery for Near an Hour; at length gave way, leaving me in full possession of their Camp also. They rallied again in Col. Robinson’s encampment, and Notwithstanding their opposition was but feeble, and I in possession of two-thirds of their camp also for More than Half an hour, yet was obliged to leave them from Several Causes, the action having Continued without Interruption for three hours, men fainting with heat and Droughth, Numbers Kild and Wounded; but the true Cause of my not totally defeating them was the want of Led, having been obliged to make use of arms and ammunition taken from the enemy.[10]

Although he failed to totally overrun the Loyalist defenders, Sumter’s attack was an extraordinary success. His 600 mounted militia surprised an estimated 500-800 Loyalists inflicting 150-200 casualties.[11] The Loyalist Prince of Wales American Regiment was knocked out of the war, Bryan’s corps scattered, and significant loss inflicted on Tarleton’s Legion infantry. Sumter confided to Pinckney: “Both British and Tories are pannick struck, and I am well Convinced that fifteen hundred men can go through any part of the State with ease. This will Not be the Case ten or fifteen days hence.”[12]

Later, on the evening of August 6, Rawdon was “pannick struck.” He recalled: “news was brought to me that Sumpter had surprised & carried that post [Hanging Rock]. The defeat of that detachment was soon confirmed by a number of fugitives from every corps . . . except the Legion infantry.”[13]

Based on this misinformation, Rawdon’s strategic dilemma seemed clear. Sumter, with nothing to stop his mounted infantry, “would lose no time in pushing for Camden” down the Flat Rock Road. “I should have had him on my rear whilst Gates pressed my front,” Rawdon determined. To his mind, the only recourse was to defeat Sumter with alacrity and dispatch. Gathering his officers around him, Rawdon “told them, in hearing of the soldiers that we were in a scrape from which nothing but courage could extricate us, & that we must march instantly to crush Sumpter.”[14]

Making a night march, Rawdon aimed for Grannies Quarter Creek and Rugeley’s Mill intending to block the main road to Camden. Imagine Rawdon’s surprise when he received word in the early morning hours of August 7 that Hanging Rock outpost had held and Sumter had withdrawn.

Rawdon ordered the 23rd Regiment to advance to Hanging Rock, secure that outpost and reconsolidate Loyalist units.[15] He then countermarched to meet Gates’s army—understanding that reoccupying his original fighting position on Big Lynches Creek was no longer feasible. Instead, Rawdon’s men occupied new ground: “I immediately hastened to occupy the bridge across the western branch of [Little] Lynches Creek.”[16]

During these maneuvers the Americans failed to detect British movements. Col. Otho Williams, Gates’s adjutant general, concluded Rawdon’s threatened attack on Caswell had been a ruse. Maybe it was. “Under the judicious mask of offensive operations,” wrote Williams, “the commanding officer of the post [Rawdon] on Lynch’s Creek evacuated it, and retired unmolested, and at leisure, to a much stronger position on Little Lynch’s Creek.”[17] Rawdon’s night-adventure march had been far from leisure. Ruse or not, fatigued British soldiers occupied a strong blocking position fifteen miles from Camden, a day’s march.

Following this drama Caswell’s militia and Gates’s Continentals finally consolidated forces at Cross Roads (near Anderson Creek) onAugust 7, triggering an unscripted moment of “brotherly affection.” This “enlivened the countenances of all parties,” Williams observed, “a good understanding prevailed among the officers of all ranks.”[18]

Gates’s new unified Grand Army, now numbering close to 3,500, resumed its march on Camden. Facing no opposition, they pushed over Big Lynches with Lt. Col. Charles Porterfield’s light infantry screening ahead of the main body. On August 8, Porterfield reached Little Lynches bridge.

Rawdon ordered what remained of the Hanging Rock troops, “weakened & depressed,” to fall back behind Grannies Quarter Creek; not because this was a better defensive position but because he could effectively support them from his new location at the bridge. He also directed the 23rd Regiment to join him while he set a trap for Gates: a trap to “seduce Gates . . . into ruinous error.” “I retired a mile from my causeway in order to get him to pass the creek,” said Rawdon, where “I might have attacked him where branches of the swamp would have hindered him from profiting by his numbers; but he was too wise to make the attempt.”[19]

Colonel Williams described the terrain:

The army advanced, but approaching the enemy’s post on Little Lynch’s Creek, it was discovered by good intelligence, to be situated on the south side of the water, on commanding ground, that the way leading to it, was over a causway on the north side to a wooden bridge, which stood on very steep banks; and that the creek lay in a deep muddy channel, bounded on the north by an extensive swamp, and passable no where within several miles, but in the face of the enemy’s work. The enemy was not disposed to abandon these advantages, without feeling the pulse of the approaching army.[20]

Gates’s army came to a standstill. While he hesitated, Rawdon saw an opportunity to attack him using a ford across Little Lynches Creek which the Americans had failed to discover. The twenty-six-year-old Lord Rawdon dreamed of victory and much else until he realized “Ld. Cornwallis was then on his way to join us; and had I achieved victory it must have been tarnished by the consciousness that I had availed myself of temporary command to snatch a palm which ought to have been reserved for my General.”[21]

For Gates and his officers, Rawdon’s position at Little Lynches Creek required a major decision, a definitive course of action. Despite the heat, inhospitable terrain, Loyalist sympathizers, and short rations, Gates had successfully marched by the most direct route towards Camden until this moment. Now, he had three basic courses of action to consider: (1) Attack, (2) Withdraw, or (3) Move against Rawdon’s left or right flank.

Baron DeKalb, second in command, urged Gates to attack, but the Hero of Saratoga decided a direct assault would fail, believing it was like “taking a bull by the horns.” Gates also opposed a withdrawal, saying it would demoralize his soldiers—especially the militia which served for a limited enlistment. He was equally dismissive of the opportunity to move against Rawdon’s right flank, knowing it would put the Grand Army out of supporting distance from Sumter’s militia in the west as well as anticipated Virginia militia reinforcements and provisions coming from Charlotte. Ultimately, after ordering several feints against Rawdon’s right, he ordered the Grand Army to march northwest up the east side of Little Lynches Creek towards Rugeley’s Mill.

Tarleton believed Gates missed a victory opportunity by not flanking Rawdon’s right and going straight for Camden to capture the town’s magazines and provisions.[22] Years later, Rawdon disputed Tarleton’s analysis. “Tarleton, with a childish pretension to Generalship, censures me for not having thus collected my troops at Camden & arraigns Gates for incapacity,” Rawdon bristled. “Gates did know . . . that there was no turning my right flank without going fifty miles down Lynche’s Creek.”[23]

Rawdon maintained his position at Little Lynches bridge until patrols alerted him to Gates’s northwest movement. When Porterfield’s Virginians were detected nearing the vicinity of Rugeley’s Mill on April 12, Rawdon ordered all forces to fall back and rally at Log Town (one and one-half miles north of Camden). He ordered Hamilton and Bryan’s North Carolinians to evacuate Rugeley’s Mill and then broke up the bridge, fortifications, and causeway at Little Lynches Creek. To safeguard Lieutenant Colonel Turnbull and his New York Volunteers at Rocky Mount (in danger of being cut off) he ordered them to move west to join troops under Maj. Patrick Ferguson at Little River.[24]

Rawdon’s delaying operation was extraordinarily successful. Rawdon commented that Gates had moved laterally thirty five miles to the west, “throwing himself across the country into the other road above Hanging Rock Creek, and gave us three days to prepare to meet him, in a country likewise very favorable for us.”[25] He jauntily declared: “My view of gaining time, of course, had succeeded.”[26]

Rawdon and the Battle of Camden: August 16-17

Sometime on August 6-7, Rawdon sent several expresses to Charleston urging Cornwallis to return to Camden. He also requested reinforcements from the Loyalist garrison at Ninety-Six which straightaway sent four light infantry companies.[27] Cornwallis, arriving at Camden on the night of August 13-14, immediately consulted Rawdon on the overall situation. Asking Rawdon his thoughts on a possible course of action, Rawdon replied: “I had intended to wait till my spies should apprize me of Gates’s being approached within an easy march, when I meant to move forward & attack him.”

According to Rawdon:

Ld. Cornwallis entered at once into the reasoning, adopted my plan, & reposed himself for its prosecution on the measures I had taken to secure information. In the meantime, he made all the arrangements which he judged expedient. It was I who brought to him the intelligence that Gates had arrived at Kingsley’s Plantation [Rugely’s Mill]. With a pencil I sketched for him the ground, with which I was well acquainted, indicating the position of the enemy, as I understood it by the relation of the spies, & pointing out a path from the main road by which we might possibly get undiscovered on the enemy’s flank. On these data the attempt against the enemy was determined.[28]

Cornwallis did not need much persuading. Like Rawdon, he quickly grasped that Gates’s army was poorly positioned and vulnerable. Even Gates’s aide Thomas Pinckney feared an attack, saying “Rugely’s was a bad position, a small detour would have placed an enemy on either flank.”[29] Cornwallis ordered the army to march at 10 p.m. (August 15) up Flat Rock Road to attack Gates at Rugeley’s the next morning.

As fate would have it, Gates determined a tactical defense would be the smartest utilization of his Continentals and untested militia. Like Cornwallis, he ordered his army to break camp at 10 p.m. and conduct a road march south to prepare defensive positions consisting of redoubts and abatis on the north bank of Sanders Creek. Gates was convinced that when the British discovered his new defensive line the next morning it would either trigger a British withdrawal from Camden or an ill-advised if not forlorn attack.

2:30 a.m.

According to Tarleton:

Lieutenant-colonel Webster commanded the front division of the army: He composed his advanced guard of twenty legion cavalry, and as many mounted infantry, supported by four companies of light infantry, and followed by the 23d and 33d regiments of foot. The center of the line of march was formed of Lord Rawdon’s division, which consisted of the volunteers of Ireland, the legion infantry, Hamilton’s corps, and Colonel Bryan’s refugees: The two battalions of the 71st regiment, which composed the reserve followed the second division. Four pieces of cannon marched with the divisions, and two with the reserve: A few waggons preceded the dragoons of the legion, who composed the rear guard.[30]

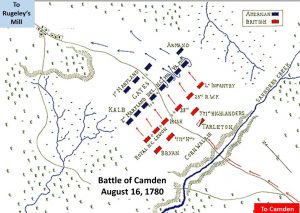

Sometime around 2:30 a.m. the columns of both armies crashed into each other, touching off a violent firefight. As the melee died down and order was restored Rawdon, dismounting his horse, examined the uniforms and buttons of several American dead and informed Cornwallis they were Continental soldiers. Both armies were surprised to discover they faced their enemy’s main army. Rawdon reassured Cornwallis “that he could not have better ground to fight upon, as it was a sort of neck between two swamps which would prevent the enemy from getting round his flanks.”[31] During the night, Gates deployed his army in line of battle while Cornwallis, deploying only the 33rd and 23rd regiments to block the road, ordered his remaining troops to sleep on their arms while still in column.

In the early dawn of August 16 Cornwallis deployed his troops. Rawdon, commanding the British left wing, would go on to distinguish himself at the Battle of Camden. His beloved Volunteers of Ireland along with the Legion infantry and Loyalist militias would confront the Continental soldiers of Gen. Mordecai Gist’s 2nd Maryland Brigade. They would bend but not break, allowing Lieutenant Colonel Webster’s division on the British right to put Patriot militia to flight and outflank what remained of Gates’s army. It resulted in the worst battlefield defeat of an American Patriot army during the Revolution.

Of his exploits Rawdon would say:

In the battle which ensued, I behaved neither better or worse than my neighbors: therefore Lord Cornwallis’s mention of me in common with Webster was the fair compliment paid as a matter of course to officers of rank after a successful action . . . But the preliminary events had not been unimportant, nor had the management been such, I venture to affirm, as had no claim upon Lord Cornwallis’s special acknowledgement either as an officer or as a man.[32]

Giving Rawdon His Due

Francis, Lord Rawdon’s pacification measures, strategy, and tactics, helped determine the outcome of the Camden battle. During his command of the Camden District (his first independent command), he gained experience as an administrator and military leader. He dealt with fleeing Loyalist refugees, selected local Loyalists like Henry Rugeley to interact with the civilian population, managed the hospital and logistical operations of the Camden base, as well as communications, troop reinforcements, and convoy movements supporting three northern outposts. He inspected his troops and his outposts to ensure that leaders and soldiers were healthy, provisioned, well-trained and mission capable.

As Camden’s senior military officer, Rawdon coordinated and conducted pacification efforts, including detaining possible insurgents. He established an intelligence network extending into North Carolina using spies, scouts and informants. He attempted to weaponize money, using it to maintain the loyalty of wavering Loyalists, buy information, and to induce Patriots to betray the American cause. He personally led his Volunteers of Ireland into the Waxhaws to recruit Loyalists and discourage/disrupt Patriot sympathizers and militia. He supported the use of patrols to destroy rebel arms caches and snatch influential Patriot leaders. One byproduct of his operations were his interactions with subordinates—building trust and trusting them.

Rawdon’s strategy and tactics, his skillful execution of delaying actions within the Camden District, is ample evidence that he more than grasped the basic tenants of what military leaders call the operational art. And rightfully so—his delaying operations altered Gates’s route of march, bought the British three extra days to prepare and consolidate forces, diverted the Grand Army to Rugeley’s Mill, and resulted in the king’s troops fighting upon favorable ground.

Author Paul David Nelson believed “Lord Rawdon had matured into a highly effective officer, showing at times brilliance in strategic and tactical thinking, logistics, and the handling of small armies against commanders who had much more military experience than he.”[33]

Following Tarleton’s lopsided defeat at Cowpens January 17, 1781, Cornwallis took most of the king’s troops into North Carolina in pursuit of Gen. Nathanael Greene. Cornwallis reposed so much faith and confidence in Rawdon that he appointed him commander of remaining British forces in South Carolina.

Later, Rawdon applied his intimate knowledge of Camden to successfully attack Greene’s larger army at Hobkirk’s Hill on April 25, 1781—his first victory as an army commander. And although his smaller force was outnumbered and eventually compelled to give ground over time, in his last significant action of the Revolution (June 19, 1781), he relieved the Loyalist garrison at Ninety-Six, breaking Greene’s twenty-eight-day siege. Rawdon safely escorted the Loyalist garrison and the king’s friends to Charlestown, from there he would leave America never to return in August 1781.[34] He would go on to do great things elsewhere; but it was in America that Francis, Lord Rawdon learned his trade, becoming a “seasoned and skillful officer” rated the “ablest of all” according to British army historian Sir John Fortescue.[35]

[1]For an excellent account see: Andrew Walters, “The Mysterious March of Horatio Gates,” Journal of the Revolution, September 24, 2020, allthingsliberty.com/2020/09/the-mysterious-march-of-horatio-gates/.

[2]Thomas J. Kirkland and Robert M. Kennedy, Historic Camden Part One, Colonial and Revolutionary (Columbia, SC: State Company, 1905), 135. Caswell with 500 militia had been marching towards Charlestown with Buford when they heard of Charlestown’s surrender. Caswell’s men returned to North Carolina via the Pee Dee region.

[3]John W. Moore, North Carolina: From the Earliest Discoveries to the Present Time (Raleigh: Alfred Williams & Co., 1880), 276.

[4]In an 1813 letter to American Col. Henry Lee, Rawdon wrote: “Camden had always been reprobated by me as a station; not merely from the extraordinary disadvantages which attended it, as an individual position; but from its being on the wrong side of the river, and covering nothing; while it was constantly liable to have its communication with the interior district cut off.”Kirkland and Kennedy, Historic Camden, 258.

[5]Banastre Tarleton, A history of the campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the southern provinces of North America (Dublin: Colles, 1787), 98.

[6]Francis, Lord Rawdon to Colonel McMahon, January 19, 1801, in Arthur Aspinall, ed., The Correspondence of George, Prince of Wales (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967), 194.

[7]John A. Stevens, “The Southern Campaign 1780: Gates at Camden,” Magazine of American History 5, no. 4 (October 1880), 262.

[8]Josiah Martin to George Germain, August 18, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Volume 14, 49-56.

[9]Stevens, “The Southern Campaign 1780,” 262

[10]Thomas Sumter to Thomas Pinckney, August 9, 1780, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, Volume 14, 540-543.

[11]Estimates of Loyalist numbers engaged vary from 500 to 1,400.

[12]Sumter to Pinckney, August 9, 1780. Colonial and State Records.

[13]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 194.

[15]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 98.

[16]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 194.The western branch was also referred to as Little Lynches Creek.

[17]Otho Williams, “A Narrative of the Campaign of 1780,” in William Johnson, Sketches of the Life and Correspondence of Nathaniel Greene (Charleston, SC: A.E. Miller, 1822), 490.

[19]Aspinall, Correspondence,195.

[20]Williams, “Narrative,” 490.

[21]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence,195.

[22]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 102.

[23]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 195.

[24]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 102.

[25]Henry P. Johnston, “De Kalb, Gates and the Camden Campaign,” Magazine of American History 8, no. 7 (July 1882), 496-497.

[26]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 196.

[27]They arrived on August 13.

[28]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 196.

[29]Robert Scott Davis Jr., “Thomas Pinckney and the Last Campaign of Horatio Gates,” South Carolina Historical Magazine 86, no. 2 (April 1985), 84-87.

[30]Tarleton, A history of the campaigns, 107.

[31]Aspinall, ed., Correspondence, 196.

[33]Paul David Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Marquess of Hastings: Soldier, Peer of the Realm, Governor-General of India (East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Press, 2005), 56.

[34]Rawdon had trouble getting home. He was captured by a French Privateer, eventually taken to France, and finally arrived in England while on parole in December 1781. See Nelson, Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 89-90.

[35]John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. New York, 1997), 131. Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings, eventually The Earl of Moira, would go on to serve in the Napoleonic Wars, defeat the fierce Gurkhas as Governor-General of India (1813-1824), and serve as Governor of Malta from 1824 until his death in 1826.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...