In May 1780, British Maj. Patrick Ferguson outlined a plan for constructing fortifications and securing the province of South Carolina. His proposals hinged on fortifying the junctions of major land and water routes from Charlestown (today Charleston) to prominent villages across the interior. Although known primarily for his design of a breech-loading rifle, Ferguson had learned facets of military engineering at Britain’s Royal Military Academy at Woolwich, and had overseen the reconstruction of the fort at Stony Point on the Hudson River when it was re-occupied by British forces in 1779.

Ferguson was appointed by Gen. Sir Henry Clinton to Inspector of Militia Corps on May 22, 1780, only ten days after the fall of Charlestown, with the directive of organizing Loyalist militia regiments in the backcountry districts.[1] Like Clinton, Ferguson believed that the backcountry populace was comprised predominately of loyal subjects who would rise to arms upon the arrival of British forces. Ferguson argued that British troops, with the assistance of Provincial regiments and Loyalist militia raised from amongst the local inhabitants, could “very easy afterwards with a very small force, by the establishment of 4 or 5 Block house redoubts, to command at once all the Principle avenues & means of transportation by land & water where they cross each other; so as to check in their infancy all combinations of the disaffected.”[2] In other words, Ferguson maintained that by fortifying a few strategic points throughout the interior of South Carolina, the loyal civilians of the backcountry would assume responsibility for their own security and swiftly subdue the rebellion at minimal expense in casualties and capital to the British government.[3]

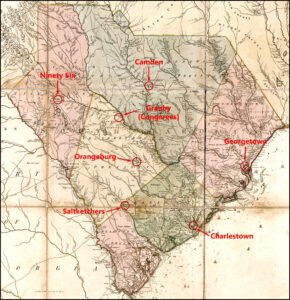

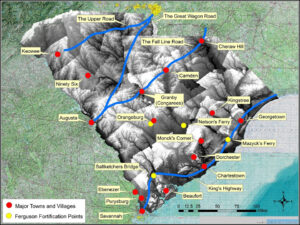

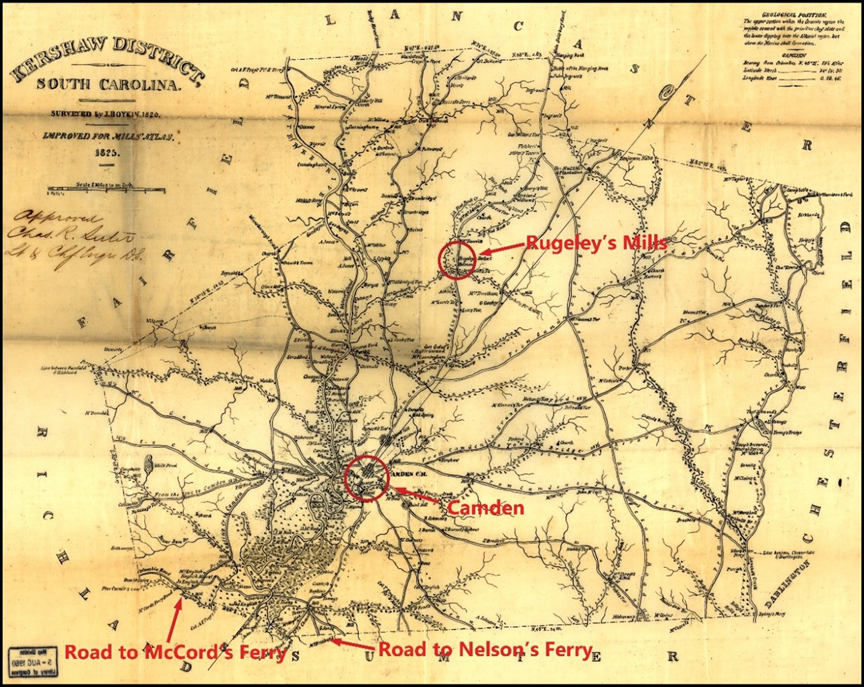

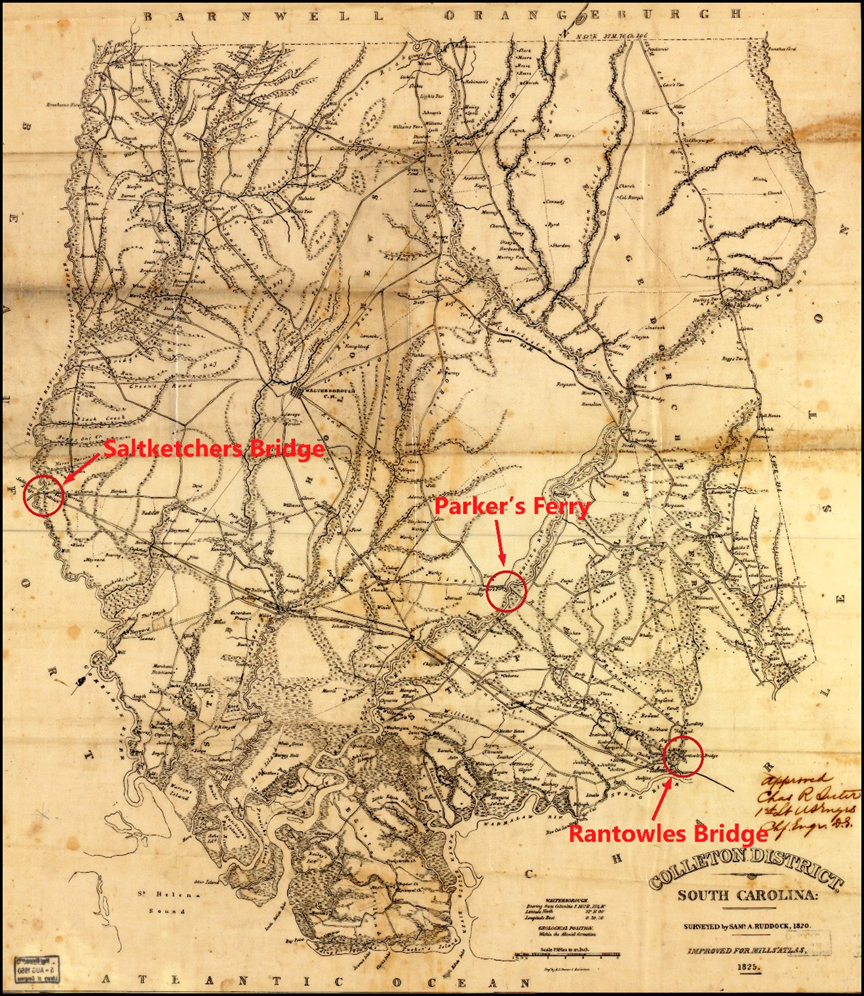

Ferguson’s plan called for each blockhouse to be strategically placed in a location that would not only prevent rebel parties from gathering and organizing, but also intercept the transport of provisions and munitions necessary for maintaining the war effort. To accomplish this goal, Ferguson proposed four blockhouses located at road and river junctions to monitor the approaches to Orangeburg, Saltketchers, Camden, Congarees, Ninety Six, and Georgetown (Figure 1). According to Ferguson:

One work of this sort at Orangeburgh ca[u]s[e]way & river, one upon the Saltketchers road & river, one upon the upper Santee Ferry leading to Pedee & overlooking the roads to Cambden, Congaree & 96, with the upper navigation, & a fourth upon the Lower Santee river & George town road would enable us, with one third of the force otherwise necessary, to cover & posses this Country, command its resources, & give a free passage & safe retreat to & from every post without to which it might be necessary to detach.[4]

The villages of Camden, Ninety Six, Orangeburg, and the Congarees (also known as Granby) were in the backcountry. Camden was situated along the Wateree River, while Ninety Six lay near the Saluda River. Orangeburg was positioned near the North Fork of the Edisto River. The Congarees was just below the confluence of the Broad and Saluda Rivers. Saltketchers was a small Loyalist community situated along the present-day Salkehatchie River. Georgetown is a coastal port city on the Pee Dee River about halfway between Charlestown and Wilmington.

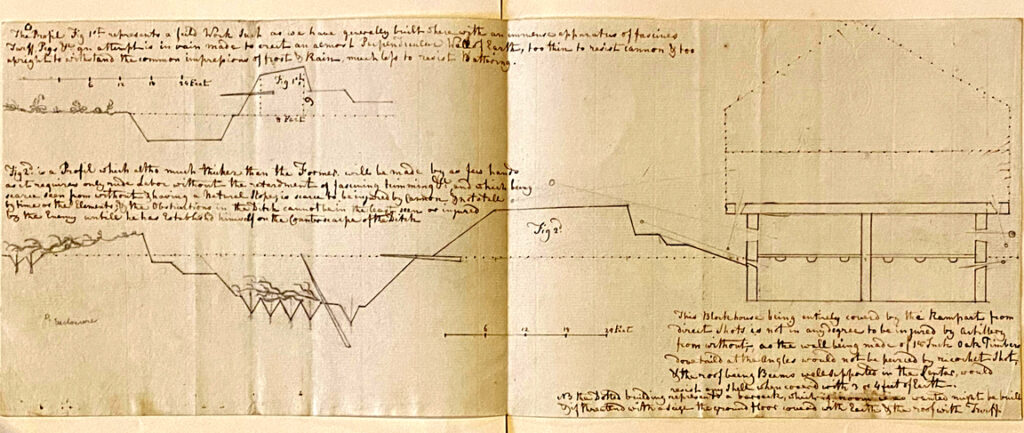

Ferguson’s May 16, 1780, proposal outlined specific plans for constructing blockhouses and converting two-story buildings into fortifications. Although he understood that the most secure fortifications were constructed with masonry revetments and arched casemates, he acknowledged that “this would require a great sum of money, a considerable length of time & great exertions of labor.” As a result, he argued that “the abundance of timber & of rough carpenters in America enable an Engineer to procure by contract without any trouble in a very short time & for a trifle of expence block houses to answer every purpose of casemates, & to secure the garrison from assault.”[5] Ferguson explained:

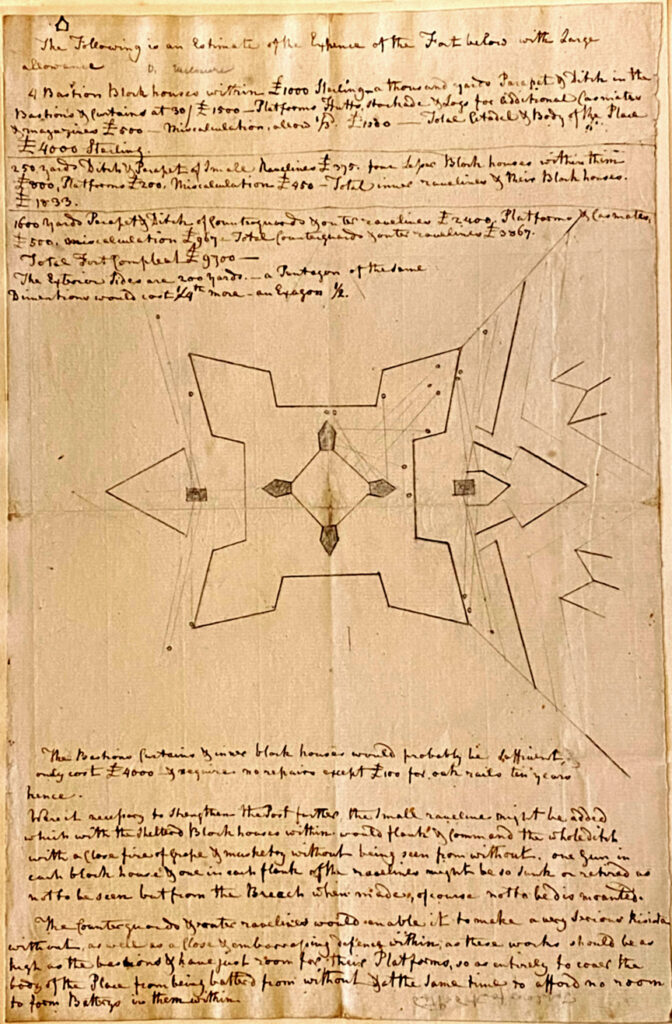

The Block houses should have five sides Bastion Fashion. The timbers both of the walls and roof of oak Eighteen Inches Square, & dovetailed at the corners, so as to resist ricochet shot & shells. One block house upon this Principle for every Bastion of the Fort placed within & sheltered by the Ramparts from Direct Shots, with loop holed stockade by way of curtain to run from the one to the other, would for a mere song of expence form at once Barracks that would last for ever . . . Casemates against shells & a retired Citadel within to secure a weak Garrison from alarm & assault & to enable a strong one to defend all the other works to the last without danger of a storm, & afterwards to begin a new Defence within.[6]

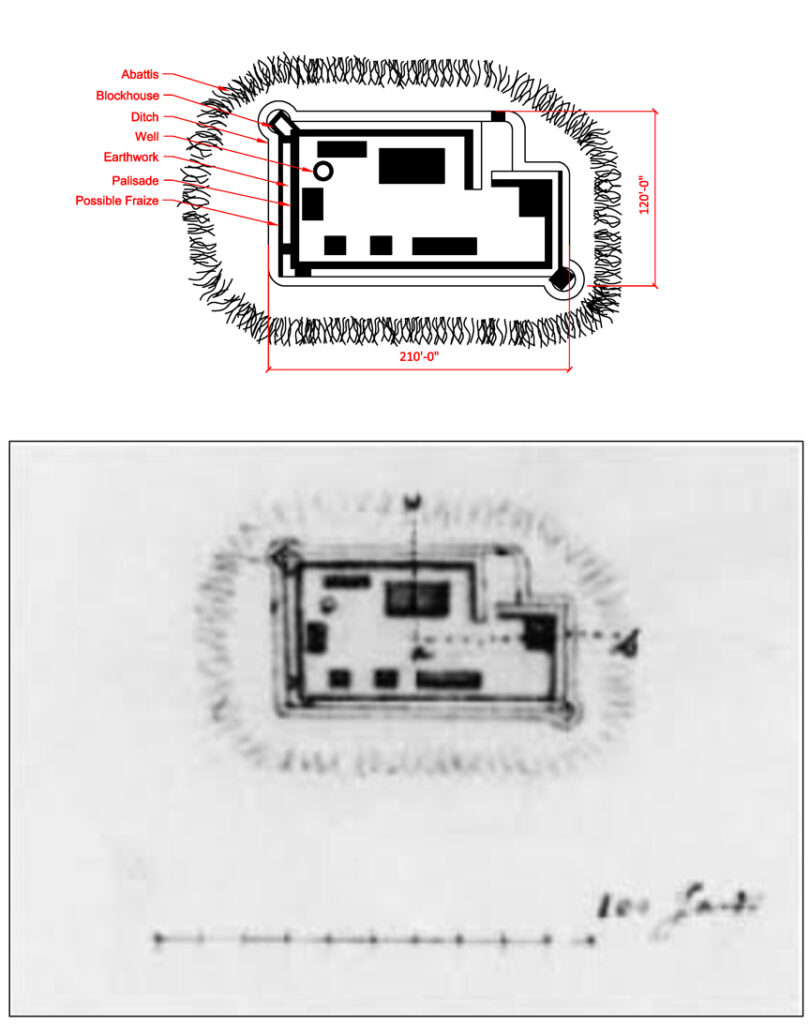

Ferguson drafted a plan for a small fort employing a typical four-bastion trace, but rather than placing blockhouses as the corner bastions, he recommended constructing four pentagonal blockhouses within the fort to act as strongpoints at opposing angles (Figure 2). The pentagonal form of these blockhouses maintained the typical shape of a bastion but could stand alone as a defensive structure with enfilading fields of fire. While the bastions allowed enfilading fire along the outer walls, the placement of the blockhouses would allow added cover throughout the interior of the fort in the event its walls were breached. The fort was designed to shelter the garrison from incoming fire while allowing a flanking “loop-holed fire of musketry crossing all sides.”[7]

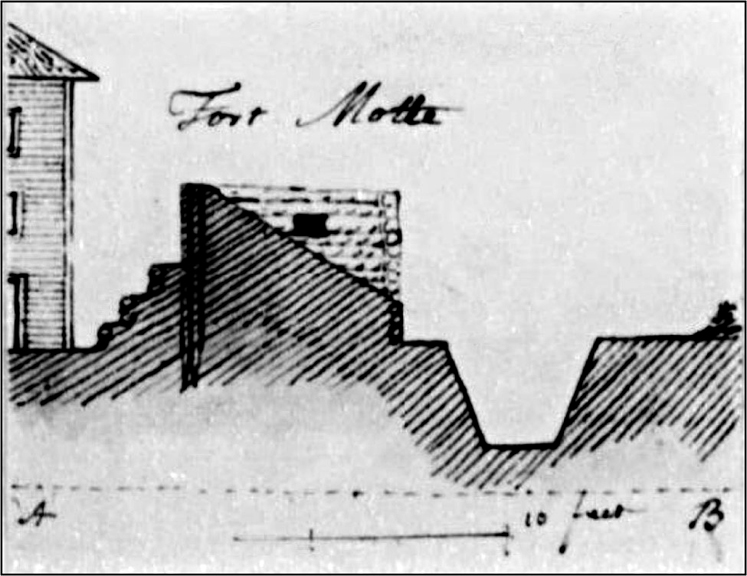

A profile of Ferguson’s proposed blockhouse design shows that it would have been protected from direct fire of light artillery and small arms by a rampart (Figure 3). The wall consisted of thick oak for protection against ricochet. The roof was constructed of beams with central supports and covered with several feet of soil to resist artillery shells. Ferguson also proposed an optional upper floor that would function as barracks. He estimated that the work could be constructed at a cost of £4,000 sterling, including the parapet, ditch, platforms, huts, stockade, and logs for casemates and magazines. He recommended constructing a work of this type only at Charlestown while placing individual blockhouses at strategic points across the interior.

While the blockhouse was a component of his plan for a small four-bastion fort, it’s form is consistent with the isolated blockhouses that he recommended at the junctions of roads and river crossings across the interior. He explained:

These block houses are singularly advantageous as forming at once barracks citadel & casemate, they may be raised of strong rough timbers by means of negroes in 4 or 5 Days & covered from summons by a redoubt, which could not be look’d at without a force deliberately assembled with cannon, nor taken or maintain’d whilst ten men remain’d in the Block house within. For each Post 30 Invalided soldiers with as many militia & 2 iron guns would prove sufficient.[8]

Ferguson was careful to specify that the blockhouse should be placed either “on a commanding eminence where an enemy would have difficulty in establishing himself near enough to support miners; or on a flat ground such as every where offer[ed] in this country, where there is water within two or three feet of the surface, so that miners cannot possibly cover themselves, or indeed approaches be carry’d on but by sap.” In addition to their pentagonal shape to allow enfilading fire, another key strategic benefit was that the blockhouses were designed to be portable. As Ferguson explained, “these blockhouses have other singular advantages, they can be prepared in a place of security beforehand, transported to the post to be occupy’d & in a week put up so as to secure the troops against every thing but an army with a train of heavy artillery: and if the fort is afterwards abandoned, they can either be carry’d off to answer the same purpose elsewhere, or burnt so as to render the Post indefensible.”[9]

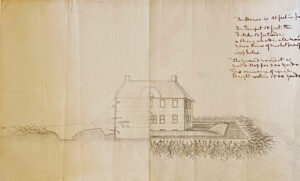

Ferguson also prepared a plan for converting a two-story building into a strongpoint (Figure 4). This fortification consisted of an earthen redoubt surrounding a building, which Ferguson noted measured “45 feet in front.”[10] The exterior of the earthwork was enclosed with abattis, and the fortification contained two lines of musket-proof loopholes. This plan was similar to Ferguson’s proposal to fortify the Lining’s residence near Charlestown. The Lining’s plantation was situated on the Ashley River, nearly opposite Charlestown, and provided a commanding view of the area.[11] On March 31, 1780, Ferguson wrote to Clinton:

Linings house may be converted into a two story Block-house surrounded by a Redoubt, and an Epaulement made by way of Curtain as at Savannah behind the abattis, so as to render it with two pieces of cannon a very defencible post; and as it has a narrow front and a great area within, for to lodge waggons stores &c.[12]

Ferguson requested that Clinton direct Maj. James Moncrief to provide engineers to construct the work, which he estimated could be completed in no more than three days.

Although Clinton praised Ferguson’s “skill as an Engineer” in a May 13 letter to Lord George Germain, it is not known if any of his proposals were implemented.[13] Interestingly, Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour commented to Lord Charles Cornwallis on May 30 that “as to Ferguson, his ideas are so wild and sanguine that I doubt [e.g., fear] it would be dangerous to entrust him with the conduct of any plan.”[14] Complaints about Ferguson were a common theme in correspondence from Balfour during late May through July 1780, with him declaring on June 27 that “I find it impossible to trust him out of sight.”[15] Nonetheless, Ferguson continued to hold the rank of Inspector of Militia Corps until his death at Kings Mountain.

Ferguson’s proposal to erect blockhouses on the Orangeburg causeway and river, the Saltketchers road and river, the upper Santee River, and the lower Santee River was intended to control the transportation infrastructure, and thus the province, with few troops and at minimal cost.[16] South Carolina was connected with the other colonies by four “interstate” road systems, consisting of the Upper Road, the Great Wagon Road, the Fall Line Road, and the King’s Highway (Figure 5). A network of smaller “intrastate” roads and paths connected the various towns and villages across the interior with these large roadways. Interestingly, rather than covering these four large “interstate” roadways, the four fortification points proposed by Ferguson were situated to the east of the Fall Line Road and principally appear to have been intended to secure the “intrastate” routes to and from Charlestown.

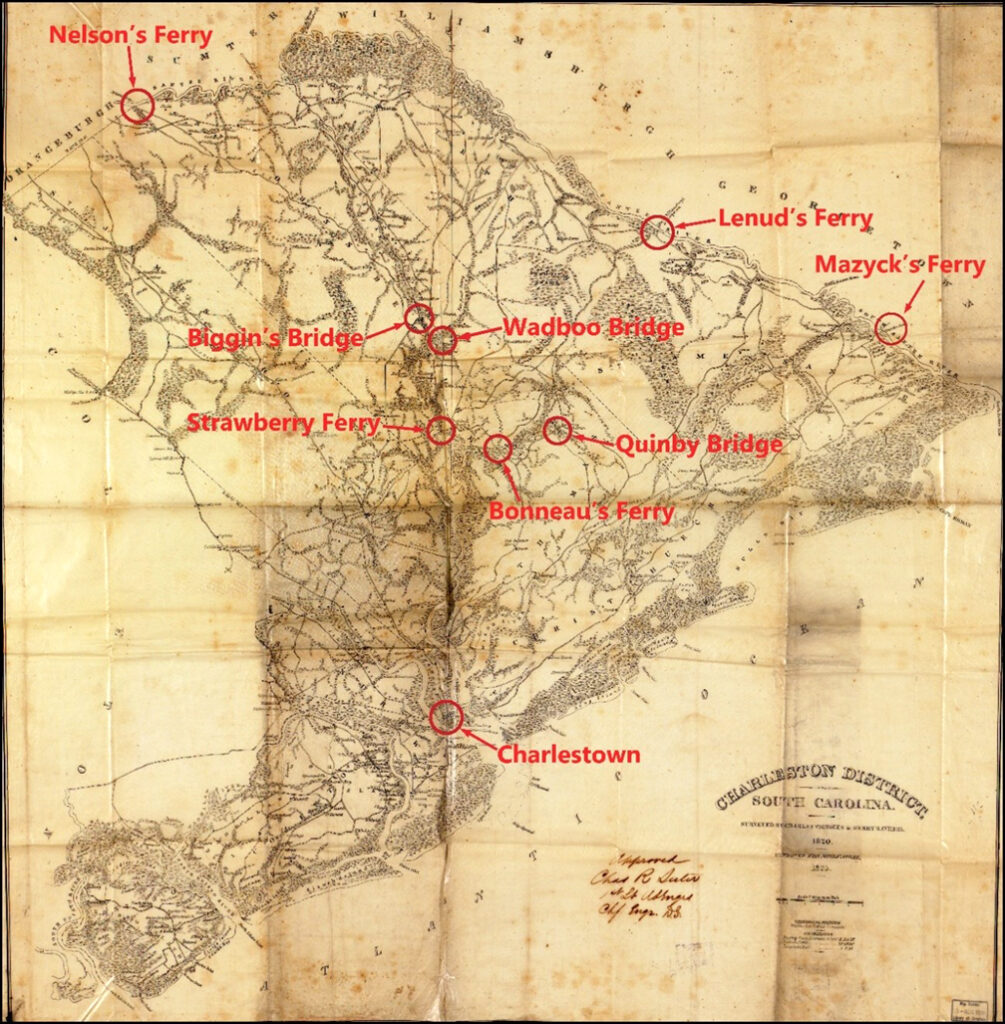

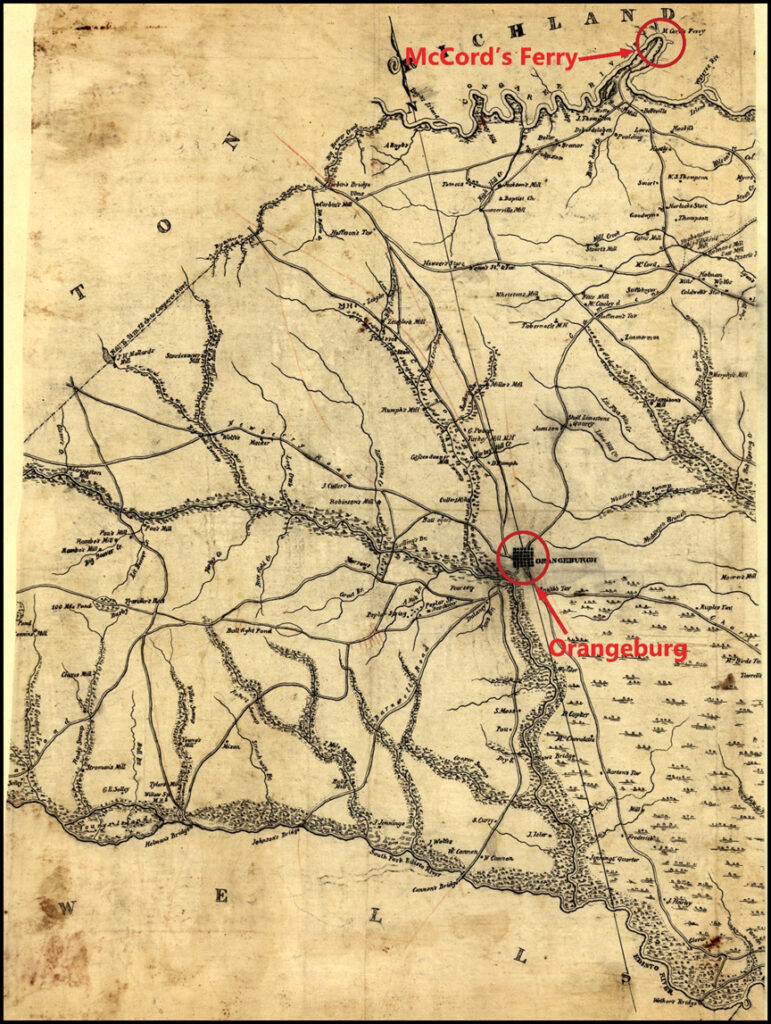

As British forces rapidly moved to secure the backcountry after the fall of Charlestown, detachments commanded by Cornwallis and Balfour crossed over the Santee River via Nelson’s Ferry and Lenud’s Ferry on their way to seize the villages of Camden and Ninety Six. Nelson’s Ferry was located on the upper Santee River and was the primary crossing point between Charlestown and Camden (Figure 6). Once across the Santee River, the road forked with one route following the east side of the Wateree River directly to Camden and another meandering northwestward toward the Pee Dee River. To the south of the Santee, the road leading to Nelson’s Ferry also continued westward with forks leading to Granby (Congarees), Orangeburg, and Ninety Six.

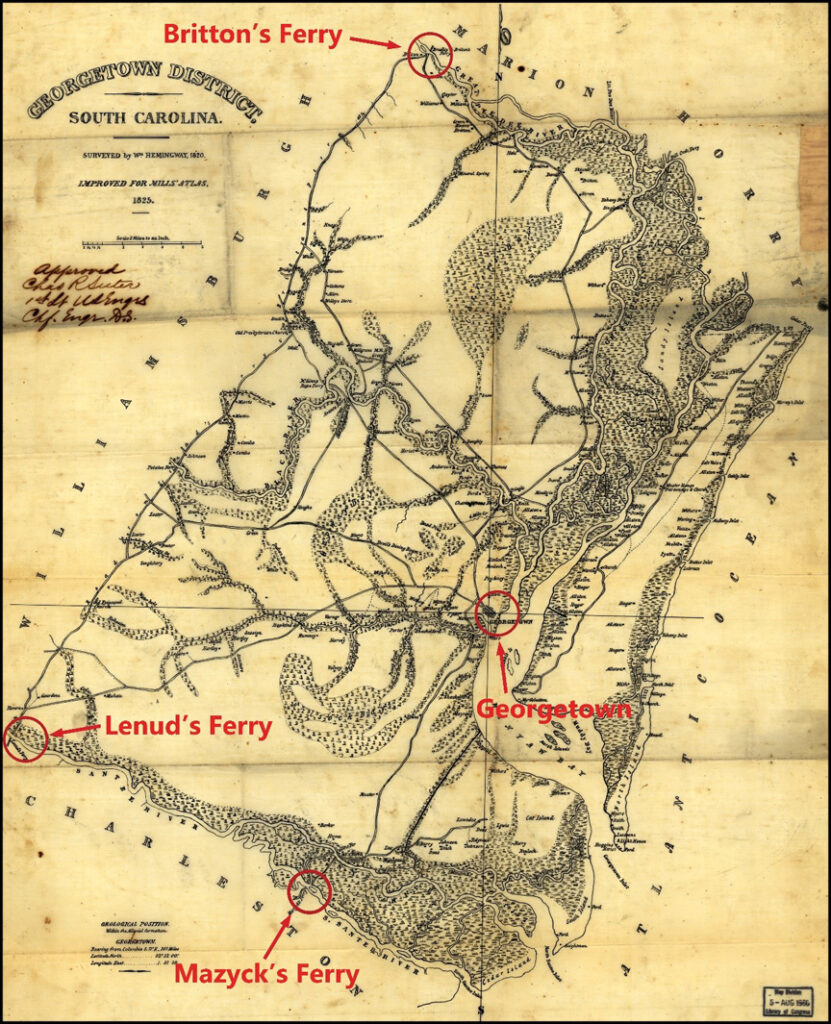

The location of Nelson’s Ferry at a junction of these routes leading to the most prominent villages in the backcountry is consistent with the fortification point on the upper Santee River suggested by Ferguson. The identification of the ferry on the lower Santee River is less clear. Historic mapping shows two ferries situated below Nelson’s Ferry with direct roads to Georgetown: Lenud’s Ferry and Mazyck’s Ferry; a January 25, 1781, dispatch from Balfour distinguishes “Lenew’s Ferry” from “the lower ferry of Santee.”[17] Given the location of Mazyck’s Ferry on the King’s Highway, its position is consistent with Ferguson’s description of the proposed fortification point on the lower Santee River.

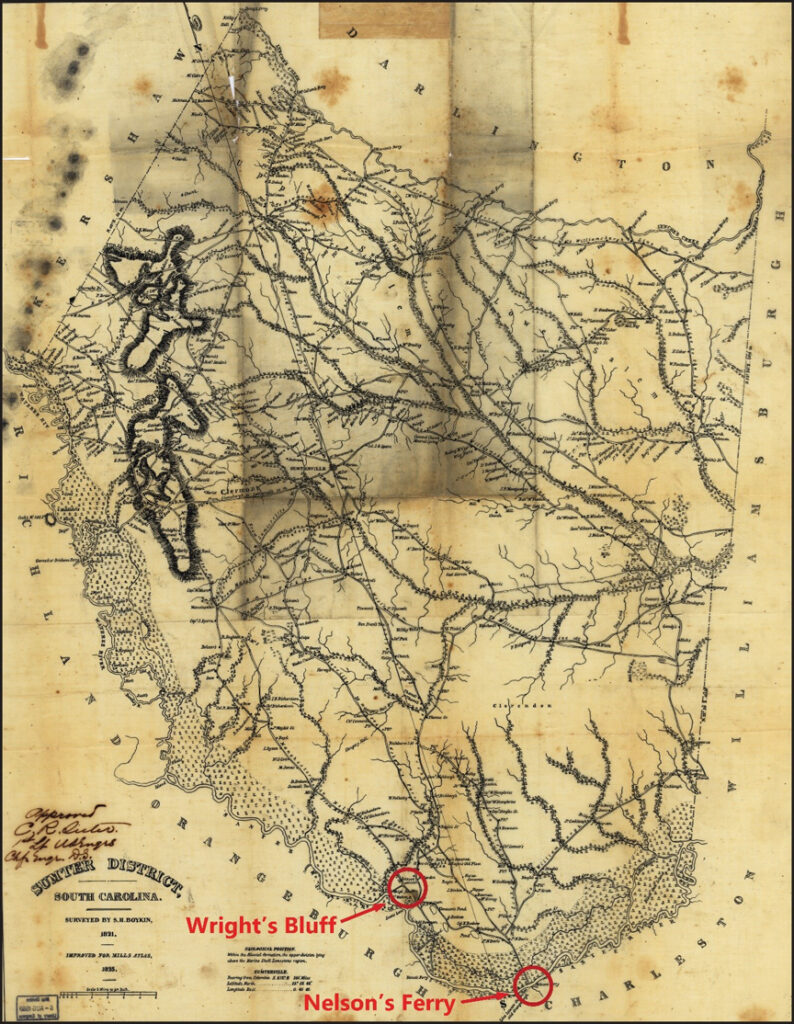

The roads from Charlestown to Nelson’s Ferry, Lenud’s Ferry, and Mazyck’s Ferry were also connected by several other ferries and bridges. The direct road from Charlestown to Nelson’s Ferry; Balfour encamped at Nelson’s Ferry in June 1780, before advancing to Ninety Six. British forces had fortified Nelson’s Ferry by early-September 1780, to secure the communications with Charlestown.[18] According to American Col. William Moultrie, the British fort was located on the south side of the river, which would have offered a view of the landing and command of the approaches to the Congarees and Ninety Six (Figure 7).[19] By late-December 1780 or early-January 1781, Fort Watson was constructed at Wright’s Bluff on the north side of Santee River to guard the road from Nelson’s Ferry to Camden.

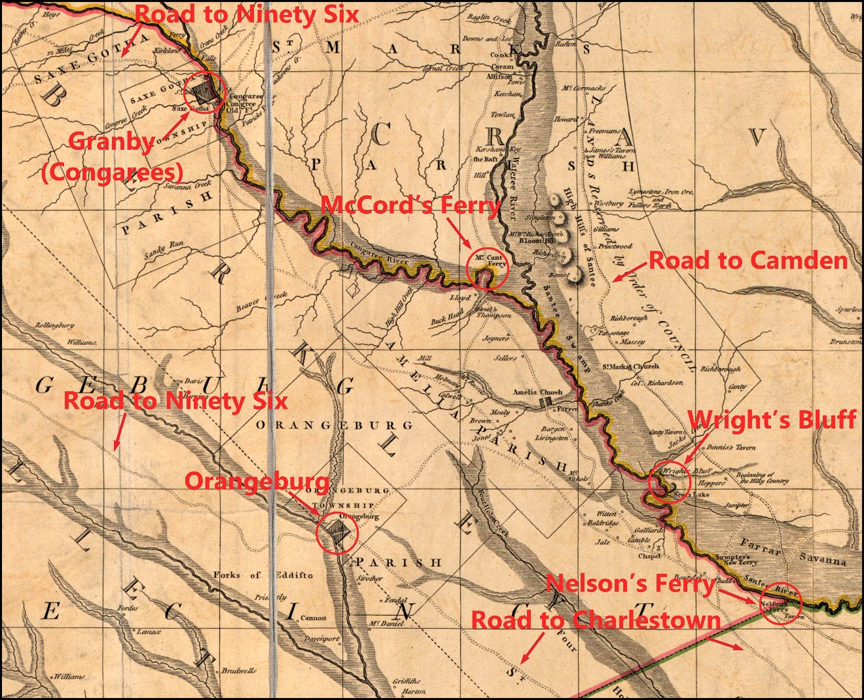

The road on the south side of the Santee River at Nelson’s Ferry continued to the northwest where it forked, with one route going to McCord’s Ferry and another to Orangeburg. The latter route also forked near the headwaters of Four Holes Creek with the southern road continuing to Orangeburg and a northern road going to Granby (Figure 8). The road over McCord’s Ferry followed the west side of the Wateree River directly to Camden Ferry (Figure 9). Although Ferguson had only recommended fortifying Nelson’s Ferry to guard the passes between Charlestown and Camden, British forces also established fortified posts at Thomson’s house and Fort Motte near McCord’s Ferry for this purpose.

The roads to Granby and Orangeburg both continued westward to Ninety Six. Although Ferguson proposed fortifying Nelson’s Ferry to secure the passes to and from Camden, Granby, and Ninety Six, his plan did not recommend fortifying these important villages themselves. Ferguson did recommend fortifying the Orangeburg causeway and bridge. The direct road from Charlestown to Orangeburg crossed the North Fork of the Edisto River on the west side of the village (Figure 10). Ferguson reconnoitered Orangeburg in June 1780, and reported that the courthouse was enclosed by a stockade. Although he recommended strengthening the post by adding abattis, he did not mention expanding the works. During the mid-nineteenth century, historian Benson Lossing reported that remnants of British earthworks were present roughly a half-mile west of the village, which suggests that some type of fortification was constructed at or near the causeway and bridge.[20]

Charlestown and Georgetown were connected by two direct roads: one that crossed the Santee River over Lenud’s Ferry and a second via Mazyck’s Ferry (Figure 11). Ferguson had proposed fortifying the ferry on the lower Santee River to secure the lines of communication between the two towns. The location of Mazyck’s Ferry at the junction of the King’s Highway and the Santee River would have made it a strategic point on the landscape. The King’s Highway was a coastal route that connected the villages of Georgetown, Charlestown, and Savannah.

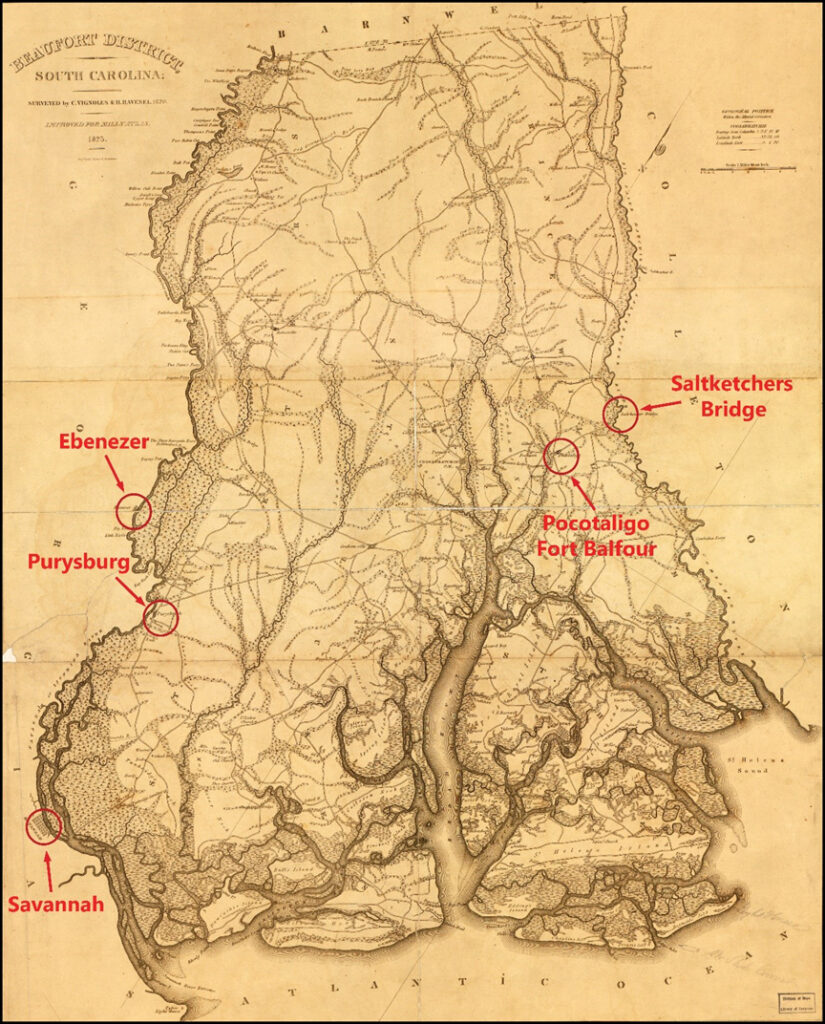

While Mazyck’s Ferry (or the lower ferry) connected the King’s Highway with the road to Georgetown to the northeast of Charlestown, it was linked with Savannah to the southwest by the Saltketchers Bridge (Figures 12 and 13). The bridge over the Saltketchers River was constructed prior to the American Revolution, but was destroyed by American militia in March 1780. The roads from Saltketchers Bridge ran westward to Purysburg and Savannah; southward to Beaufort on Port Royal Island; and eastward to Charlestown. A causeway was also present on both sides of the river. Although the bridge had been destroyed, the river was passable by ferry and there was a “Ferry House about a quarter of a mile from the River.”[21] Ferguson recommended fortifying the Saltketchers road and river to secure the communications between Charlestown and Savannah.

British forces constructed Fort Balfour in the community of Pocotaligo to secure the lines of communication between Charlestown and Savannah.[22] The post was also referred to as Pocotaligo Fort in American pension records and was established in either late 1780 or early 1781.[23] It was situated along the road from Saltketchers Bridge and “was approachable only by three points, all of which were well guarded by a deep creek and cannons.” Period descriptions of Fort Balfour only mention that it was well-fortified and surrounded with abattis. Vanbiber’s tavern was located approximately four-hundred yards from the fort and was used as a hospital by the British garrison. When the post was captured in April 1781, American forces “burnt the house and leveled the fort with the ground.”[24]

The description of the fort’s destruction might suggest that Fort Balfour was a fortified private residence; the burned house may also refer to Vanbiber’s tavern, which was located outside of the fort. Although Fort Balfour was constructed on the road from the Saltketchers River, it was situated approximately five miles southwest of the bridge.

Of the four points that Ferguson recommended securing using his improved blockhouse redoubts, British forces appear to have constructed some type of fortification at or near three. Although the post at Mazyck’s Ferry, or the lower ferry on the Santee River, does not appear to have been fortified, the British military constructed a redoubt at Nelson’s Ferry; a possible earthen redoubt at the Orangeburg causeway and bridge; and a bastioned fortification (either an earthen redoubt or stockade) at Fort Balfour on the road to the Saltketchers River and bridge. Unfortunately, all three of these sites have been heavily impacted by modern construction activities. Nelson’s Ferry is presently under Lake Marion; the possible earthworks described by Lossing in 1850 as being to the west of Orangeburg have been destroyed by modern urban sprawl; and the site of Fort Balfour in Pocotaligo has been impacted by the construction of South Carolina State Highway 17 and McPherson Road, as well as residential and commercial buildings.[25]

Because only a few partial historical descriptions exist, a detailed comparison of Ferguson’s engineering plans and the actual form of the fortifications built by the British military at these specific positions cannot be made. However, prior to his death at Kings Mountain, Ferguson was present at Ninety Six and Orangeburg, and offered suggestions for their fortification. He was also present at Monck’s Corner during the April 14, 1780, engagement. Given the early establishment of the post at Monck’s Corner, it is possible that it incorporated elements of his proposed design. Although the blockhouse at Biggin’s Bridge also may have followed his suggested improvements, it was unfinished when the post fell in November 1781 and no period maps or descriptions of its form could be located. Interestingly, period descriptions of the fortified barn/blockhouse at Rugeley’s Mills indicate that it was similar to the blockhouse design proposed by Ferguson in that it appears to have been enclosed by an earthwork. Similarly, the fortifications at Manigault’s Ferry also consisted of a log blockhouse, possibly similar to Ferguson’s design. No other details about the form or design of the fortifications at Rugeley’s Mills and Manigault’s Ferry have been identified.

Although the stockade at Orangeburg was already present during Ferguson’s reconnaissance in June 1780, one account indicates that the crossing over the North Fork of the Edisto River was fortified. Unfortunately, these earthworks are no longer extant, and no other details are presently known. In contrast, archaeological investigations at Ninety Six have identified elements of the British fortification system that allow a substantive comparison with Ferguson’s proposals. In addition, the existing historical and archaeological data at Fort Motte and Fort Granby also allows a comparison between these works and Ferguson’s plan for fortifying a two-story building.[26] Although both Fort Granby and Fort Motte were established after Ferguson’s death, it is possible that his ideas were incorporated into their architectural design. Both posts consisted of an existing building that was enclosed by an earthwork similar to his plan for converting a two-story building into a strongpoint. Of particular significance, period engineering plans of both Fort Granby and Fort Motte were prepared by American forces.

The fortifications at Ninety Six offer the best comparison to Ferguson’s improved blockhouse proposal. Upon assuming command of Ninety Six in June 1780, Balfour reported to Cornwallis that an engineer, Lt. William Frazer of the 42nd Regiment, could oversee the fortifications at both that post and at Augusta. Notably, Balfour insisted that Frazer conduct the work “without Ferguson’s assistance [emphasis in original].”[27] Ferguson had accompanied Balfour to Ninety Six and endeavored to persuade the senior officer to implement his blockhouse design. Cornwallis was concerned about the monetary costs and approved the works proposed by Balfour, which consisted of three small redoubts and abattis, on the caveat that they be “made on the footing of field works.”[28] On July 11, 1780, Ferguson offered to personally finance any additional expense for construction of fortifications at Ninety Six.[29] The following day, Balfour dispatched him to “a very strong post near Fair Forest [where] he shall not have it in his power to do mischief.”[30] A little over a week later, Ferguson reported to Cornwallis from Fair Forest: “I shall confine myself to what relates to the militia and principally to what appears to me the cheapest method of supplying them with provisions with the least opening for prerequisite or imposition.”[31] It appears that the fortification plan outlined by Ferguson, as well as his proposal to personally pay for any additional costs at Ninety Six, did not meet the approval of his superior officers. He remained at Fair Forest through at least August 9, when Capt. Abraham DePeyster was placed in command of an advanced guard to cover the country north of Ninety Six to the Pacolet River.[32]

In July 1780, Balfour returned to Charlestown and Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger assumed command of Ninety Six. The fortifications were largely completed by late October and were expanded under the direction of Lt. Henry Haldane in December. The blockhouses were reportedly constructed of notched logs, similar to the design proposed by Ferguson, and were located on the northeastern side of village near the star redoubt.[33] Given that Clinton considered Ferguson to be a skilled engineer, it is possible that Cruger may have implemented some of his proposals. Notably, upon his arrival at Ninety Six, Haldane commented that the fortifications were as strong as the best executed work and in a much better state than he had expected to find them. This suggests that Cruger received advice from someone with an academic knowledge of military fortification theory. Taking these circumstances into consideration, it is highly possible that at least one of the blockhouses at Ninety Six was constructed according to Ferguson’s plan.[34] Lt. Roderick Mackenzie, of the 71st Highland Regiment, noted that divisions were assigned to each blockhouse, which suggests that they may have been used as quarters and may have featured an upper floor similar to Ferguson’s two-tier plan. Archaeological investigations identified an outer ditch, palisade, and parapet enclosing the blockhouse bastions at the town stockade, which is also similar to Ferguson’s plan.[35]

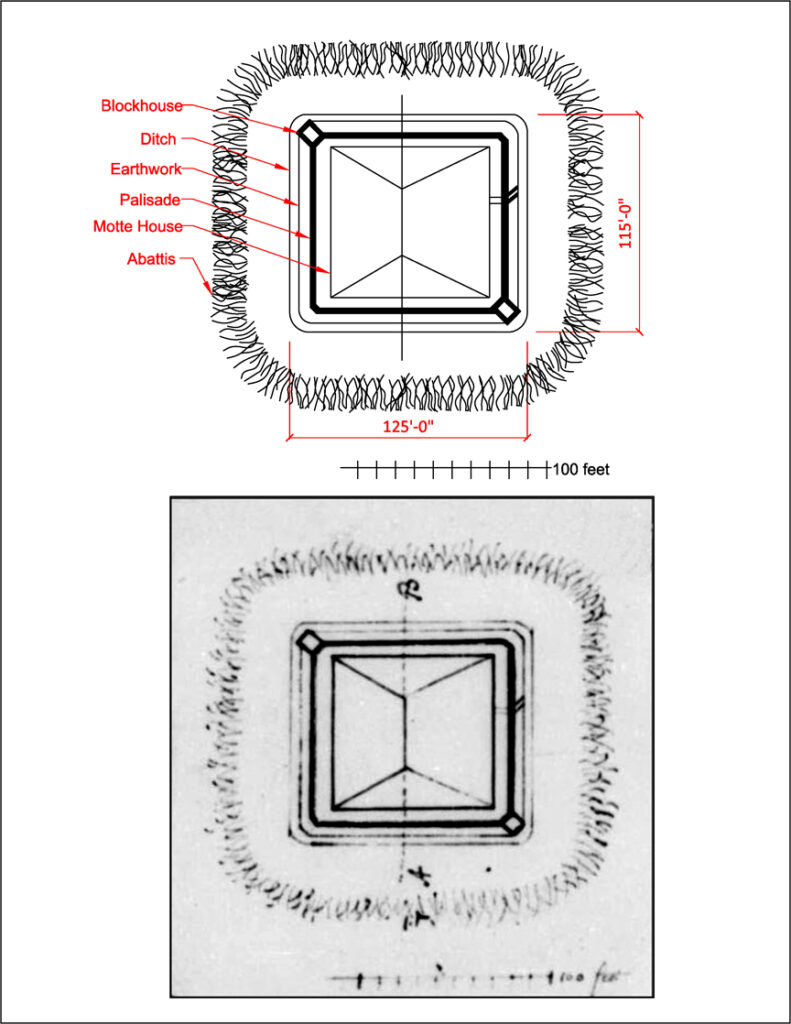

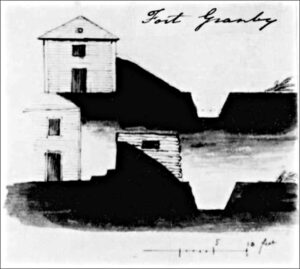

Although both Fort Granby and Fort Motte were established after Ferguson’s death at King’s Mountain, the British fortifications at these two posts provide the best comparisons with his plan for fortifying a building. Fort Granby was established in late December 1780 or early January 1781, and consisted of an earthen redoubt that enclosed the two-story residence and storehouses of Wade Hampton. Although the site of Fort Granby was not recorded archaeologically prior to its destruction, a detailed plan of the works was drafted by an unknown American engineer in May 1781 (Figure 14). Likewise, Fort Motte was established in April 1781, and consisted of an earthen redoubt that enclosed the three-story mansion home of Rebecca Motte at Mount Joseph plantation. American engineers also prepared a sketch of the British works at Fort Motte in May 1781 (Figure 15).

These contemporaneous sketches, along with the archaeological data and period descriptions, allow a comparison of both works with Ferguson’s plan for fortifying a building. The May 1781 plan of Fort Granby shows that it was a large compound laid out as a roughly L-shaped work with rounded, projecting bastions at two opposing corners. The bastion depicted on the upper left contained a blockhouse; it is unclear if the bastion shown at the lower right held a blockhouse or a gun platform. Although the profile of Fort Granby does not show a stockade revetment, the plan appears to depict a palisade along the inner wall of the parapet as well as possible fraize on the outer wall at two ends of the enclosure. The entire work was surrounded by abattis that was placed approximately thirty feet in front of the ditch.

On the other hand, Fort Motte was depicted as a rectangular work with somewhat rounded corners. The 1781 plan shows that it measured 115 feet by 125 feet; archaeological research revealed that it actually measured 115 feet by 130 feet.[36] The width of the outer ditch shown on the plan measured roughly five feet wide. The 1781 plan also shows blockhouse bastions at two opposing corners and abattis approximately thirty feet in front of the ditch. Unlike Fort Granby, the blockhouse bastions at Fort Motte did not project outward from the curtain.

The 1781 plan shows that the house measured approximately eighty by eighty-five feet across the roof. Based on the 1781 American plan, the larger rectangular building in the upper central portion of the enclosure at Fort Granby measured forty-five feet across and is consistent with the front length of the building described by Ferguson; however, the dimensions of the residence at Fort Motte were almost twice as large. Although the 1781 plan shows the house in the center of the earthwork, the archaeological investigations found that it was situated along the west wall with a plaza to the east. The 1781 plan also shows that the entrance to the fort was offset from the center of one of the longer sides of the work, but a geophysical survey shows that it was closer to a corner on one of the shorter walls.[37]

Comparatively, the sketch provided by Ferguson in circa May 1780 depicts an existing domestic residence enclosed by an earthen redoubt with an outer ditch and abattis. Although Ferguson did not include a scale, he provided measurements for the length of the house (forty-five feet); the height of the parapet (eighteen feet); and the width of the ditch (thirteen feet). Using these measurements, the length of the work proposed by Ferguson was extrapolated as approximately ninety-one feet across the inner edges of the ditch. This measurement is much smaller than Fort Granby but is fairly close to the shorter width of the rectangular enclosure at Fort Motte. The ditch proposed by Ferguson was larger than that constructed at both forts.

Based on Ferguson’s sketch, the parapet measured approximately twenty feet wide and the ditch was just over four feet deep. The 1781 plan of Fort Granby shows that the parapet was six feet tall with a twelve-foot rampart, while the ditch was four feet deep and five to seven feet wide (Figure 16). The earthwork was shown to adjoin one of the structures, which appears to represent the smaller building in the upper right corner of the plan. The two profiles of Fort Granby likely represent different buildings within the enclosure. The building in the bottom profile was situated adjacent to a blockhouse and appears to represent the long rectangular structure near the upper left corner of the enclosure. The interior of this portion of the work contained two banquettes. Notably, Ferguson did not propose blockhouse bastions in his plan for converting a two-story building into a strongpoint.

The 1781 profile of Fort Motte shows the house was enclosed by a nine-foot tall parapet that included a log palisade along the interior wall. The rampart measured from ten to eleven feet wide, with a ditch that was approximately seven and a half feet wide by six feet deep (Figure 17). Like Fort Granby, the 1781 plan shows the house situated adjacent to a bastion that was accessible by banquettes. Fort Motte contained three steps while Fort Granby had two. The blockhouses at both Fort Granby and Fort Motte appear to have been constructed with horizontal logs and contained loopholes. Another difference between both fortifications and Ferguson’s plan was the distance of the abattis from the outer ditch. While the 1781 plans of both works show the abattis approximately thirty feet in front of the ditch, Ferguson placed it directly at the outer edge. Interestingly, Ferguson’s proposal for an improved blockhouse suggested placing “a strong abattis both without and in the Ditch.”[38] Archaeological excavations at Fort Motte identified a small trench at the base of the ditch that suggests that it may have held fraize or perhaps abattis similar to Ferguson’s plan.

Although the 1780 Ferguson plan and the 1781 engineering plans of Forts Granby and Motte depict privately-owned buildings enclosed within an earthen redoubt surrounded by a ditch and abattis, there are marked differences between these defensive works. Principally, Ferguson proposed converting the building itself into a blockhouse citadel rather than erecting corner blockhouse bastions, and Forts Granby and Motte both contained log blockhouses at opposing corners. While the 1780 Ferguson plan does not specifically depict Fort Granby or Fort Motte, it bears some architectural similarities to the small portion of the Motte house shown in the 1781 military engineering map. Some elements of Ferguson’s proposal may have been utilized in the fortification of the existing Motte residence. It is also possible that British military engineers either sought out or preferred a particular type or size of house to convert into a fortification. However, the shape and layout of Fort Granby suggests otherwise and their design was most likely based on expedience.

Overall, Ferguson’s fortification plans would have certainly protected the principal routes to Charlestown from Camden, Ninety Six, Granby, Orangeburg, and Georgetown, but would have done little to secure the backcountry itself. The geographical placement of the four points that Ferguson recommended fortifying would not have prevented an enemy force from advancing from the north or west and taking these villages. This is undoubtedly a result of his belief in the overwhelming loyalty of the citizens in South Carolina, and particularly in the backcountry. His confidence in the near-universal loyalty of the citizens and the certainty that they would take up arms in large numbers, resulted in a misperception that the backcountry villages did not require significant protection. To hold South Carolina, Ferguson’s plan required that the British military need only to secure Charlestown and the backcountry would take care of itself.

[1] Henry Clinton to Charles Cornwallis, May 28, 1780, in The Cornwallis Papers: The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Theater of the American Revolutionary War, ed. Ian Saberton (East Sussex: The Naval & Military Press Ltd., 2010), 1:53.

[2] Patrick Ferguson, “Plan for Securing the Province of So. Carolina &c.,” May 16, 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 99, Folio 7, William C. Clements Library.

[3] Patrick Ferguson to Cornwallis, June 6, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:102–103.

[4] Ferguson, “Plan for Securing the Province of So. Carolina &c.”

[5] Patrick Ferguson, “[Plans for a fort in North America],” 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, Small Clinton Maps 364, William C. Clements Library.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ferguson, “Plan for Securing the Province of So. Carolina &c.”

[9] Ferguson, “[Plans for a fort in North America],” Henry Clinton Papers, Small Clinton Maps, 364.

[10] Patrick Ferguson, “[Plan of a two-story building converted into a strong point],” 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, Small Clinton Maps, 349a, William C. Clements Library.

[11] Anthony Allaire, “Diary of Lieutenant Anthony Allaire,” in Kings Mountain and Its Heroes, ed. Lyman C. Draper (Cincinnati: Peter G. Thompson, 1881), 489; Uzal Johnson, Captured at Kings Mountain, ed. Wade S. Kolb III and Robert M. Weir (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2011), 8.

[12] Ferguson to Clinton, March 31, 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 90, Folio 35, William C. Clements Library.

[13] Clinton to George Germain, May 13, 1780, Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 98, Folio 2, William C. Clements Library.

[14] Nesbit Balfour to Cornwallis, May 30, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:73–74.

[15] Balfour to Cornwallis, June 27, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:242.

[16] Ferguson, “Plan for Securing the Province of So. Carolina &c.”

[17] Balfour to John Wigfall, May 25, 1781, The Cornwallis Papers, 6:264.

[18] Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 (Dublin: Colles, Exshaw, White, H. Whitestone, Byrne, Moore, Jones, and Dornin, 1787), 173.

[19] William Moultrie, Memoirs of the American Revolution, Volume II (New York: David Longworth, 1802), 280.

[20] Benson Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution in the Carolinas & Georgia, ed. Jack E. Fryar, Jr. (Wilmington: Dram Tree Books, 2005), 159.

[21] Allaire, “Diary of Lieutenant Anthony Allaire,” 486–487; Johnson, Captured at Kings Mountain, 5, 54.

[22] Steven D. Smith, Report of Findings: The Search for Fort Balfour and Coosawhatchie Battlefield (Columbia: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2005).

[23] Pension deposition of Tarleton Brown, October 22, 1832, revwarapps.org/s21665.pdf; Robert B. Roberts, Encyclopedia of Historic Forts (New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1988), 709.

[24] Tarleton Brown, Memoirs of Tarleton Brown (New York: Lagare Street Press, 2021).

[25] Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book, 159.

[26] Steven D. Smith, The Battles of Fort Watson and Fort Motte (Yardley, PA: Westholme, 2024); Steve D. Smith, James B. Legg, Tamara S. Wilson, and Jonathan Leader, “Obstinate and Strong”: The History and Archaeology of the Siege of Fort Motte (Columbia: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2007).

[27] Balfour to Cornwallis, June 24, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:239.

[28] Cornwallis to Balfour, July 3, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:245.

[29] Ferguson to Cornwallis, July 11, 1780, in The Cornwallis Papers, Volume I, Chapter 14: Correspondence between Cornwallis and Ferguson, 291–292.

[30] Balfour to Cornwallis (12th July 12, 1780), The Cornwallis Papers, 1:248–249.

[31] Ferguson to Cornwallis, July 24, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:293.

[32] Balfour to Cornwallis, July 12, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:248; Ferguson to Cornwallis, August 9, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 1:301–303.

[33] Marvin Cann, Old Ninety Six in the South Carolina Backcountry, 1700–1781 (Fort Washington: Eastern National, 2000), 20–23; Jerome A. Greene, Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report: Ninety Six (Denver: National Park Service), 92, 99–114; Lossing, Pictorial Field-Book, 154.

[34] Henry Haldane to Cornwallis, December 9, 1780, The Cornwallis Papers, 3:281; Clinton to Germain, Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 98, Folio 2; Greene, Historic Resource Study and Historic Structure Report: Ninety Six, 90–91.

[35] Ibid; William Johnson, Sketches of Life and Correspondence of Nathanael Greene, Volume II (Charleston: A. E. Miller, 1822), 140; Roderick Mackenzie, Strictures on Lt. Col. Tarleton’s History (Sheridan: Franklin Classics, 1787, reprinted 2008), 145; Stanley South, Exploratory Archaeology at Holmes’ Fort, the Blockhouse, and Jail Redoubt at Ninety Six (Columbia: South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1971), 43–44.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ferguson to Clinton, Henry Clinton Papers, Volume 90, Folio 35.

2 Comments

Nice work, Brian. The drawings from the Clements Library are pure gold! You must have gotten shivers when you found them. Can’t beat the primary documents.

Brian,

Fantastic read and materials! Glad to see the dots connecting Ferguson’s time at Woolwich learning military engineering come to life.