European colonial powers often employed enslaved Black soldiers in the New World to combat their enemies. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, Spain freed, trained, and armed fugitive slaves from Georgia and the Carolinas. Britain was an exception. Except for employing enslaved Jamaicans in the failed 1741 effort to conquer the Spanish city of Cartagena in today’s Colombia, that nation generally avoided arming those in bondage.

During a 1676 rebellion in Virginia led by Nathanial Bacon, Black residents briefly joined forces with whites against Gov. William Berkley, and they torched the capital of Jamestown. The insurgency fell apart after Bacon’s death that October. In the aftermath, the colony’s General Assembly passed strict laws forbidding Black Virginians from owning or carrying weapons without government approval. In subsequent decades, the numbers of enslaved Africans brought to the colony soared.

No census was taken in colonial Virginia in the years just prior to the Revolution, but scholars today estimate that about 200,000 of the province’s population of some 500,000 were enslaved. In 1772, Virginia’s royal governor, the Scottish earl Lord Dunmore, recognized that enslaved Africans posed a security threat to white Virginians. “The people with great reason trembled at the facility that an enemy would find in procuring such a body of men,” he noted.[1] Those in bondage were “attached by no tie to their masters or to the country, on the contrary, it is natural to suppose their condition must inspire them with an aversion to both.” That made them ripe “to revenge themselves by which means a conquest of this country would inevitably be effected in a short time.”[2]

At the time, he was thinking of Spanish or French invaders. Three years later, the conflict brewing between Britain and its North American colonies gave a different slant to the presence of enslaved African Americans. In March 1775, the Second Virginia Convention, made up of the colony’s elite, met in Richmond to name delegates to the Second Continental Congress. Swayed by Patrick Henry’s powerful rhetoric they also agreed to create an armed militia. Lord Dunmore, meanwhile, had received instructions from King George III ordering him to halt appointments to the Congress and to prevent ammunition from falling into Patriot hands.

On the night of April 21, 1775, the royal governor ordered British marines to seize twenty gunpowder kegs stored in the magazine that stood in the heart of Williamsburg, the colony’s capital since 1699. An angry armed mob quickly formed outside the Governor’s Palace to protest. Dunmore had no troops to protect him or his family, but city leaders convinced the crowd to disperse when Dunmore assured them that he was simply protecting the powder from a rumored revolt of the enslaved. Later, when the governor heard that a British officer had been insulted on the street, he warned that if he, his family, or his officers were harmed, “he would declare freedom to the slaves and reduce the city of Williamsburg to ashes.”[3]

Meanwhile, more than a thousand Patriot militia gathered in Fredericksburg to march on Williamsburg to force the powder’s return. Alarmed, the governor armed enslaved members of his staff and reiterated his willingness to emancipate those in bondage to protect his family and supporters. News of the April 19 battles at Lexington and Concord had yet to reach Virginia. Peyton Randolph, the speaker of the colony’s House of Burgesses and president of the First Continental Congress, lived near the Palace and within sight of the Magazine. He was preparing to leave Williamsburg for the start of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia when he received news of the planned march.

Fearing a bloodbath on his very doorstep, the speaker chose to fudge the truth to calm passions. In a hastily-written letter to Patriot militia leaders in Fredericksburg, he explained that the governor “thinks he acted for the best” and that “His Excellency has repeatedly assured several respectable gentlemen that his only motive in removing the powder was to secure it, as there had been an alarm from the County of Surry,” just across the James River.[4] Enslaved Africans there were said to be planning an insurrection, a rumor that “at first seemed too well founded,” though it later proved groundless.[5]

Randolph went on to claim that the Scottish earl had given his word “that the powder shall be returned to the Magazine, though he has not condescended to fix the day.” The speaker concluded, “The governor considers his honor at stake,” and therefore “will not be compelled” to reverse course. It would be more effective to let him return the powder of his own volition rather than by force. Randolph begged the militia to stand down, warning that “violent measures may produce effects, which God only knows the consequences of.”[6] After heated debate, the Patriots officers in Fredericksburg disbanded their men. Days later, Patrick Henry raised his own militia to march on Williamsburg but turned back when Dunmore offered to pay for the seized gunpowder.

By then, the governor was prepared to defend his home. “He has fortified his house, with swivel guns at the windows, cut loopholes in the Palace, and has plenty of small arms,” wrote Norfolk merchant James Parker.[7] The earl later reported to London that he was “defending myself by arming the persons of my family,” a term that likely included free and enslaved staff.[8] A nineteenth-century historian who interviewed surviving participants wrote that the earl “armed his servants together with the Shawnees hostages”—young warriors from Dunmore’s 1774 war against indigenous peoples in the Ohio Valley—and that “parties of Negroes mounted guard every night at the Palace.”[9]

The May 4 Virginia Gazette reported that several Black men not in the earl’s employment had “offered to join him to take up arms” when Henry menaced the capital. According to the paper, however, Dunmore “threatened [them] with the severest resentment should they presume to renew their application.”[10] Loyalist John Randolph, the colony’s attorney general and brother of Peyton, later confirmed this under oath, reporting that the earl had rejected their help, ordering them “to go about their business.”[11] The crisis passed.

Dunmore’s threat to arm Black Virginians proved effective in deterring two planned Patriot attacks, yet it provoked outrage among whites throughout the colonies while giving enslaved Americans hope of liberation. “We never imagined him an enemy,” wrote “Virginius” in the June 29, 1775, Virginia Gazette. Once considered “an inoffensive, easy, good-natured man,” he had become “suddenly as black as an Ethiop,” a reference to the African kingdom of Ethiopia. The man heralded as the colony’s champion in winning the recent war against Native Americans was now derided as a liar, blunderer, and worse. “Can any confidence,” the writer asked, “be reposed in a murderer?”[12]

The governor admitted privately that he had “stirred up fears” among white colonists “which cannot easily subside, as they know how vulnerable they are in that particular.” Yet he expressed no regret, on the “grounds of self-preservation.” He had used the only obvious strategy available to forestall patriot assaults—and succeeded. “I had full right to make use of any means I could avail myself of, for my defense against a furious people.”[13]

Dunmore refrained from further public mention of emancipation, but on May 1 he informed British officials in Boston and London that he intended to “raise such force from among Indians, Negroes, and other persons, as would reduce the refractory people of this colony to obedience.” He specifically planned “to arm all my own Negroes and receive all others that will come to me whom I shall declare free.”[14]

Flight to Norfolk

On June 8, 1775, fearing capture or assassination, Lord Dunmore fled Williamsburg under cover of darkness and took up residence on the Fowey warship that lay off Yorktown. The following morning, the sloop Otter arrived from Boston under the command of Capt. Matthew Squire. The Mercury, captained by John McCartney, arrived July 11 to replace the Fowey, under the command of George Montagu, which was needed in Nova Scotia.

By then, at least some Black Virginians had found refuge aboard Montagu’s ship. “Negro slaves, now on board the Fowey, were under the governor’s protection” wrote one Patriot, adding that they were therefore “in actual rebellion, and punishable as such.” The writer then suggested that the Patriots counter Britain’s “bloody plan by arming our trusty slaves ourselves,” an idea that failed to gain traction.[15] McCartney, meanwhile, refused to take the Fowey refugees on board his ship, but Squire agreed to house them on the Otter.

On July 17, Dunmore moved his base from the vulnerable site of Yorktown to the shipyard at Gosport, upstream from Norfolk on the southern branch of the Elizabeth River. Enslaved Virginians immediately began to flee their Patriot owners and provide military intelligence as well as piloting skills to the British. Squire soon took on board his ship “a number of slaves belonging to private gentlemen” from the Norfolk area.[16] By protecting fugitives, the naval officers proved themselves to be of a “most unfriendly disposition to the liberties of this continent,” warned the local pro-Patriot newspaper, the Norfolk Intelligencer. The publication called for residents to “have no connections or dealings with Dunmore, Squire, and the other officers of the Otter sloop of war.”[17] Under pressure from city leaders, the captain ultimately agreed to turn over the refugees.

An increase in runaway slave Virginia Gazette advertisements in subsequent months suggests that enslaved people nevertheless continued to flock behind British lines. Aaron and Jimmy, two enslaved Hampton men owned by Patriot Wilson-Miles Cary, for example, found their way to the shipyard that summer. Others climbed aboard British ships sent to seize provisions from plantations. Dunmore used some of the escapees as ships’ crew, messengers, and spies. Among the most valuable refugees were ship pilots such as Joseph Harris of Hampton. He provided intelligence to the British but was forced to flee to a Royal Naval vessel when he was discovered. His knowledge of local waters proved invaluable.

As early as September, a Patriot source estimated the Scottish earl had “about one hundred Negroes, and from twenty to thirty Tory volunteers” to fight alongside two hundred or so redcoats and marines.[18] British sources do not confirm this, possibly because Dunmore preferred not to broadcast the arming of Black troops. Harris took part in the British naval force that attacked Hampton in October, the first Revolutionary battle south of New England, and narrowly escaped recapture by the Patriots. Other Black sailors and pilots likely were part of that expedition.

By early November, more than a thousand patriot troops were on the march from Williamsburg to Norfolk, with more expected to arrive from North Carolina. With few white loyalists at his side and little hope for major British reinforcements, Dunmore wrote an emancipation proclamation on November 7 freeing “all indentured servants, Negroes, or others” under control of rebels, if they were “able and willing to bear arms.”[19] Still, he hesitated to make the controversial decree public without the Crown’s approval.

A week later, on November 15, Dunmore led a force of redcoats and white and Black loyalists, including armed enslaved Africans, on a mission to seize patriot arms and ammunition at Kemp’s Landing, in what is now Virginia Beach. A patriot militia ambushed the column just outside of the small town, but Dunmore quickly rallied his men, and the Patriots fled into the neighboring swamp where several drowned.

Two Black Loyalists, one armed only with a sword, chased Patriot leader Col. Joseph Hutchings, the Norfolk delegate to the Virginia Convention. The middle-aged officer, separated from his comrades, desperately tried to outrun his pursuers in the fading light. When they were just a few paces behind, he turned and pointed his pistol at a sword-carrying enemy. The shock of seeing the familiar face may have shaken his aim, since the gun flashed but the bullet missed its target. One of his adversaries took advantage of the moment to rush forward and slash him in the face with his sword. He and his companion then took the injured commander into custody and escorted him to Kemp’s Landing. The colonel and his assailant were acquainted: under Virginia law, Hutchings owned the unnamed man who had just captured him. Dunmore immediately published his proclamation, which was distributed widely in the colonies.

Decades later, a white woman who was staying near Kemp’s Landing hours after the battle described “an ugly looking Negro man, dressed up in a full suit of British regimentals, and armed with a gun” who searched the home where she was staying for patriot militia.[20] If her memory is correct, then the governor had established a uniformed Black fighting force even before publishing the decree.

“I am now endeavoring to raise two regiments,” Dunmore wrote to London soon after, “One of white people, called the Queen’s Own Loyal Virginia Regiment, the other of Negroes, called Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment.”[21] The former was made up of five hundred recruits of local white men divided into ten companies, while the latter initially consisted of some two to three hundred Black volunteers.

The name of the Black unit sent a powerful message, since the governor attached his own name, and “Ethiopian” was a rare term of respect accorded to Africans by Europeans. The name referred to the East African Christian kingdom and stems from an Amharic term that ancient Greeks translated to mean “burnt faces” or “born under the sun’s path.”[22] Homer praised the Ethiopian king in the Iliad, a fact that would have been known to the well-read governor. Europeans, noted sociologist W. E. B. Dubois, came to “refer to the ancient Ethiopians in exalted terms, and consider them the oldest, wisest, and most just of men.”[23]

Dunmore assigned “white officers and non-commissioned officers” to oversee the Black soldiers, who likely were organized in a similar fashion to the white troops. Twenty-four-year-old Maj. Thomas Taylor Byrd, a Virginian and officer in the British Army’s 14th Regiment, commanded both new regiments. No roster of soldiers or officers is known to survive, but the regiment drew enslaved men from Virginia and beyond. “Letters mention that slaves flock to him in abundance,” wrote Edmund Pendleton, a Patriot leader, wrote of Dunmore on November 27, “but I hope it is magnified.”[24]

Recruits flocked to Norfolk from as far away as New Jersey. The day after the proclamation was published, twenty-one-year-old and six-foot-tall Titus Cornelius escaped from his notoriously cruel New Jersey Quaker owner. Once he learned of Dunmore’s pledge he headed south, evading patrols for hundreds of miles to reach Gosport. He would go on to become what one historian called “one of the war’s most feared Loyalists, white or black,” known throughout the colonies as Colonel Tye.[25] He led a Loyalist brigade that harassed Washington’s forces until Patriots fatally wounded him in battle in 1780.

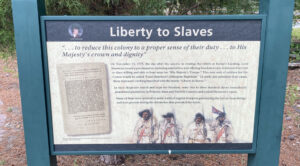

With limited muskets available, some Loyalists likely had to make do with swords, lances, pikes, and other weapons. At least a few Ethiopian Regiment members were issued surplus 14th Regiment coats, though most probably wore coarse white linen or whatever clothes they could obtain. A December 2 Gazette article reported that the Black soldiers sported the motto “Liberty for Slaves,” perhaps sewn into their outer garment.[26] If this claim is accurate, the slogan was a direct rebuke to Patrick Henry’s followers who wore his famous phrase “Liberty or Death” on their uniforms.

The Battles of Great Bridge

The regiment’s first action was around Great Bridge, a dozen miles south of Norfolk on the southern branch of the Elizabeth River. Dunmore had ordered a fort built at the eastern side of this strategic crossing in the land route from Williamsburg to Norfolk to halt the Patriot march. Col. William Woodford, who commanded the Patriot’s Virginia 1st Regiment, arrived on the western bank of the river on December 2 and estimated “their numbers in the fort are said to be 250, chiefly Blacks,” though this figure likely was inflated.[27]

Most of the regiment’s fighting at Great Bridge took place during the first week of December at a ferry landing a half-dozen miles downstream. British regulars and some three dozen Black soldiers guarded the site. Patriot Lt. Col. Charles Scott learned of the enemy camp on December 3 and gathered a unit to reconnoiter. “A party of the king’s troops and several Negroes” immediately crossed the river and attacked, “upon which some of our people gave ground,” he reported.[28]

The sight of Black men wielding guns apparently unnerved many Patriot soldiers, who fled. They soon returned with reinforcements, gunning down at least seven of the enemy, including the British officer who had led the initial assault. Survivors retreated to the safety of their breastwork adjacent to the ferry house. This minor clash at a forgotten ford marked the first recorded fight in British North America pitting a unit of Black soldiers against white Americans.

At midnight on December 5, a party of one hundred Patriots climbed quietly into small boats and paddled across the river to attack the same outpost. They outnumbered the British and Loyalist defenders on the opposite shore by more than three to one. A watchful Black sentry sounded the alarm by shooting at the approaching shirtmen. “Our people, being too eager, began the fire without orders, and kept it up very hot for near fifteen minutes,” Scott wrote later that day. “We killed one, burnt another in the house, and took two prisoners (all blacks), with four exceeding fine muskets.” The remainder—twenty-six Black men and nine white—“escaped under cover of the night.”[29] Unsure if the enemy would regroup and launch a counterattack, the Patriots crossed back to their camp, ending what proved a botched assault.

They took with them the prisoners, including “Negro Ned,” an enslaved man from Kemp’s Landing. He told them that he had come from Norfolk that day “with twenty-odd Blacks and three whites.” Ned added that “all the Blacks … at the Great Bridge [were] supplied with muskets, ammunition, etc., and ordered to use them.”[30] The second captive was George from Suffolk, who estimated there were four hundred Black soldiers in Norfolk and ninety at Great Bridge. The captives could not or would not say how many redcoats and white Loyalists were with them.

Capt. Charles Fordyce of the 14th Regiment, meanwhile, rushed more men from Fort Murray to the smoking ruin of the ferry redoubt to secure the position. “We still keep up a pretty heavy fire between light and light,” an exhausted Scott wrote later in the day to another Patriot officer, adding that two of his men were dead. “Last night was the first of my pulling of my clothes for twelve nights successively. We are surrounded with enemies. Believe me, my good friends, I never was so fatigued with duty in my whole life.” He had to break off the letter. “A gun fired,” he wrote, with startling immediacy. “I must stop.”[31]

In a December 6 fight at the same ford, Patriot militia killed “one white man and three Negroes” and took three Ethiopian Regiment members captives, “two of which are wounded (one mortally),” according to Woodford. The Patriots confiscated six muskets and three bayonets, additional evidence that regiment members carried guns. Yet despite their overwhelming numbers, the Patriots abruptly abandoned the fort when four men approached with a cart carrying supplies to the Great Bridge fort and began firing on them. “All escaped unhurt,” Woodford noted of his troops. “One man only was grazed by a ball in the thumb.”[32]

When Dunmore received intelligence on December 8 that North Carolina Patriots were poised to arrive at Great Bridge with cannon that could destroy the wooden fort, he ordered an attack the next morning. Ethiopian troops were to “make a detour and fall in behind the rebels a little before break of day.” They would draw the Patriots out of their Great Bridge trenches to aid their embattled comrades. British members of the 14th Regiment would then “sally out of the fort and attack their breastwork.”[33] For reasons that went unrecorded, the diversionary attack did not take place, and the British frontal assault that morning led to a deadly rout.

The defeated British and Loyalist troops retreated to Norfolk, boarding the Royal Navy ships anchored offshore. One Virginia Patriot wrote to Richard Henry Lee in Philadelphia that the “regiment of sables is now dispersed,” adding that, “the poor deluded wretches are daily brought into our camp in great numbers.” Their fate, he added, “is not yet determined.”[34] Black soldiers captured by the Patriots at Great Bridge were treated as insurrectionists rather than prisoners of war. When Dunmore sought to exchange Ethiopian Regiment members for captured rebels, Patriot officials did not take him seriously. One suggested instead that “he supposed we must sell them.”[35]

Black captives were sent to Williamsburg’s notorious jail, where many died of disease, while whites were interned elsewhere. A Loyalist sergeant named Henry Crouch also was incarcerated in the jail; his two names and rank suggest that he was a white man who served as an officer in the regiment. Many of those who survived the crowded and sickly conditions eventually were sent to labor in the Chiswell lead mines in western Virginia, where they produced bullets for the Patriot cause under harsh conditions.

Lord Dunmore’s Floating Town

The regiment, however, continued to take part in military actions, including the January 1, 1776, assault ordered by Dunmore to destroy warehouses on Norfolk’s waterfront used by patriot snipers against the Royal Navy fleet. Several buildings were burnt. The patriots used this attack to set fire to the rest of the port city, which was left in ruins. Fighting continued through the month. After a January 20 landing by British and loyalist forces, the patriots recovered the bodies of “one sailor and two Negroes.”[36]

The crowded flotilla numbered some one hundred vessels carrying as many as three thousand people. The waterborne community had its own court and police system, as well as clerics to cater to Anglicans as well as Methodists. One British officer dubbed the fleet the “floating town.”[37] That winter, illness took a heavy toll on military and civilian personnel. The March 8 issue of one of Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazettes noted that the “jail distemper rages with great violence on board Lord Dunmore’s fleet, particularly among the Negro forces.”[38] Black residents of the shipboard community likely endured more crowded and squalid conditions than whites.

By early spring, Dunmore had built a secure land base at Tucker’s Mill Point, less than a mile downstream from the ruins of Norfolk, to nurse the sick and drill Black troops. A moat and earthworks, along with naval guns, protected the site from patriot attack. “We have in this little fort four ovens, and pretty good barracks for our Ethiopian Corps,” the governor wrote to London. While he had trouble attracting white loyalists to the Queen’s Own Loyal Regiment, his effort to recruit Black soldiers was proceeding “very well.” The goal was to prepare the men for a spring assault on Williamsburg. Yet as the regiment’s members trained for battle “a fever crept in amongst them which carried off a great many very fine fellows,” Dunmore noted, suggesting affection and respect for the soldiers.[39]

Despite the high mortality rate, enslaved people continued to slip across the moat at night or arrive in small boats. Virginia planter Edmund Ruffin complained that four of his human chattels were “in Lord Dunmore’s service,” while Landon Carter reported that “a slim Black fellow by name of Phil” had left his plantation wearing his new waistcoat and breeches, presumably “to increase the Black regiment forming in Norfolk harbor.”[40]

Continental Army general Charles Lee arrived in Norfolk harbor in early May, with orders from the Second Continental Congress to defeat Dunmore’s forces, but he left within days after determining that the Patriots lacked the firepower and naval superiority needed to dislodge the enemy. He soon departed for South Carolina, where a British invasion was expected. An outbreak of smallpox soon forced the Dunmore to evacuate his forces from Tucker’s Mill Point so that the Black troops could be inoculated against the deadly disease. This medical procedure required a long recovery, thus making the base susceptible to attack.

Last Stand at Gwynn’s Island

In late May, the flotilla relocated to Gwynn’s Island, fifty miles to the north and adjacent to the western shore of the Chesapeake. Many of the regiment’s members died of disease during the brief journey, though a British naval captain later reported that the “Negro troops got through the disorder with great success.”[41]

Gwynn’s Island was located close to hundreds of tobacco plantations with a high density of enslaved people; many escaped bondage and reached the new encampment. Black and white Loyalists from around Chesapeake Bay flocked to serve Dunmore. John Emmes, an American pilot forced to serve the British, noted that “many Negroes came in and joined him.”[42] Those included eight of planter Landon Carter’s enslaved men, who stole one of his boats, along with his son’s gun, powder, and bullets.

New recruits to the regiment were offset, however, by deaths due to virulent diseases such as typhus and malaria. In a June 26 letter to London, Dunmore reported that a fever “has proved a very malignant one and has carried off an incredible number of our people, especially the Blacks.” Despite recruiting “six or eight fresh men every day” there were soon only 150 “effective men” available for duty. The June 14 Gazette reported, “Lord Dunmore’s whole army is now reduced to forty regular soldiers, and two hundred of the black fusiliers.”[43] A long drought that made fresh water scarce combined with dwindling supplies exacerbated the spread of disease.

On July 9, a Patriot force aided by several cannons attacked Gwynn’s Island and the ships lying offshore, forcing Dunmore to evacuate. Many of the sick were left behind, and corpses went unburied. An estimated 500 members of the Ethiopian Regiment perished on the island, along with some 150 whites. The flotilla then headed north into Maryland to seek desperately needed fresh water. During a July 23 foray up the Potomac River to fill casks, Patriot militia wounded at least a half dozen British and Loyalist troops, and one Patriot reported that “three white men and four Negroes were found dead on the shore.”[44] By early August, the fleet was anchored off Cape Henry, at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, preparing to disperse to New York, Britain, and St. Augustine.

On August 6, three British tenders in the fleet carried Loyalist soldiers to the beach close to where English settlers paused in 1607 on their way to settle Jamestown. A squadron of sixty rebels rushed to the site, and the two sides exchanged shots before the landing party withdrew. “We took one prisoner who came ashore with two Negroes,” a Patriot soldier noted, “but the Negroes made their escape.”[45] This was the last recorded clash between members of the Ethiopian Regiment and Virginia Patriots. Dunmore and the remaining Black soldiers then departed for New York.

On August 20, Thomas Jefferson wrote from Philadelphia that the governor “had the blacks shipped off to the West Indies,” implying that they were sold.[46] In fact, soldiers of the Ethiopian Regiment, some with their families, arrived off Staten Island on August 14. They participated with British troops in the Battle of Long Island that began on August 26. The September 14 Virginia Gazette reported that the earl accompanied Highlanders and Hessians “the whole day,” while his Black soldiers took part in various skirmishes. The Patriots claimed to have captured “Major Cudjo, commander of Lord Dunmore’s Black regiment,” though whether he was real or imagined is unclear.[47]

In September, Dunmore’s corps was absorbed into Gen. Henry Clinton’s Black Pioneers. Though they were not issued weapons, they received the same pay as whites, and at least four Black men were promoted to the ranks of corporal and sergeant. In 1783, with the British evacuation of New York in the wake of their defeat, dozens of Black Virginians who had served with Dunmore emigrated to Nova Scotia to escape re-enslavement by the victorious Patriots. A few went on to establish the colony for emancipated enslaved people in Sierra Leone, on the coast of West Africa.

[1] George Livermore, An Historical Research Respecting the Opinions of the Founders of the Republic on Negroes as Slaves, as Citizens, and as Soldiers Read Before the Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston: New-England Loyal Publication Society, 1863), 169.

[2] William Wirt Henry, Patrick Henry; Life, Correspondence and Speeches (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1891), 262.

[3] “Deposition of Dr. William Pasteur. In Regard to the Removal of Powder from the Williamsburg Magazine,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 13 No. 1 (July 1905), 49.

[4] Philip Alexander Bruce and William Glover Stanard, “Virginia Legislative Papers,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 13 (1905): 50.

[5] Robert L. Scribner and Brent Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, the Road to Independence (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973–1983), 3:63.

[6] Ibid.

[7] James Parker to Charles Steuart, May 6, 1775, Charles Steuart Collection, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

[8] Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: US Department of the Navy, 1964), 1:259.

[9] John Burk, Skelton Jones and Louis Hue Girardin, History of Virginia (Petersburg, VA: Dickson & Pescud, 1804), 3:403.

[10] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, May 4, 1775.

[11] “Deposition of John Randolph in Regard to the Removal of the Powder,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 15 (1907): 150.

[12] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, June 29, 1775.

[13] Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Annapolis, MD: US Department of the Navy, 1964 – ), 1:259.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, July 13, 1775.

[16] Scribner and Tarter, Revolutionary Virginia, 3:385, 453.

[17] Norfolk Intelligencer, July 5 and August 16, 1775.

[18] Ivor Noël Hume, 1775; Another Part of the Field (New York: Knopf, 1966), 323.

[19] Alan Gilbert, Black Patriots and Loyalists (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 10.

[20] Helen Calvert Maxwell Read, Memoirs of Helen Calvert Maxwell Read (Chesapeake, VA: Nofolk County Historical Society, 1970), 54–55.

[21] Naval Documents, 1:1311.

[22] Stefan Goodwin, Africa in Europe: Antiquity into the Age of Global Expansion (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009), 16; W. E. B. Du Bois, The Negro (New York: H. Holt, 1915), 37.

[23] W. E. B. Du Bois, “Black Folk Then and Now,” The Oxford W. E. B. Du Bois, ed. Henry Louis Gates Jr. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 12.

[24] Peter Force, American Archives (Washington, DC: Peter Force, 1837-1853), 4th series 4:202.

[25] Pinkney, Virginia Gazette, November 23, 1775.

[26] Pennsylvania Gazette, December 13, 1775.

[27] Catesby Willis Stewart, The Life of Brigadier General William Woodford of the American Revolution (Richmond, VA: Whittet & Shepperson, 1973), 445.

[28] Purdie, Virginia Gazette, December 8, 1775.

[29] Naval Documents, 2:1299.

[30] “The Woodford, Howe, and Lee Letters,” in Richmond College Historical Papers, ed. Dice Robins Anderson (Richmond, VA: Richmond College, 1915), 113.

[31] Naval Documents, 1:1274.

[32] “The Woodford, Howe, and Lee Letters,” 114.

[33] Naval Documents, 3:141.

[34] Ibid.

[35] “The Woodford, Howe, and Lee Letters,” 146.

[36] Naval Documents, 3:905.

[37] Ibid., 6:66.

[38] Purdie, Virginia Gazette, March 8, 1776.

[39] “Lord Dunmore to Lord Germain, March 30, 1776,” in Force, American Archives, 2:160.

[40] Purdie, Virginia Gazette, January 6 and April 5, 1776.

[41] Naval Documents, 5:840.

[42] Ibid., 5:668.

[43] Ibid., 5:535.

[44] Ibid., 5:1207.

[45] Ibid., 5:477.

[46] Thomas Jefferson to John Page, August 20, 1776, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0207.

[47] Dixon and Hunter, Virginia Gazette, September 14, 1776.

One thought on “Lord Dunmore’s Ethiopian Regiment”

Thanks for your very interesting article, Andrew. There were also at least 20 black Loyalists fighting alongside White Loyalists at the Battle of the Blockhouse south of Bull’s Ferry, NJ on July 21, 1780, against several regiments under the command of Brigadier General Anthony Wayne. Thanks to the tireless research of Todd Braisted, one of the names of the Black Loyalists is known: Harry Scobey, whom Todd discovered was still with the Loyalist Commander of that Battle, Captain Thomas Ward (now a Major) two years later at a new blockhouse location at Bergen Point.