The summer meeting of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787 was an event as momentous as the eight years it took for the colonies/states to achieve independence. The failure of the Articles of Confederation, and the dismal outcome (and attendance) of the Annapolis Convention in 1786, made it clear to all concerned that a different approach was needed if peace was to be secured. From 1783 and the signing of the Treaty of Paris to 1787 and the beginning of the Constitutional Convention the states had floundered in their attempt at developing and maintaining a functioning government. The legal deficiencies of operating a national government proved too significant for the young nation to overcome. The states were functioning as separate legal districts in the absence of a national law. The Continental/Confederation Congress was little more than a voluntary association of usually like-minded individuals.

The story of the hot and humid summer of 1787 is well known. During the debates large states battled small states; slave interests battled non-slave interests; federal power battled state power; the Constitutional Convention was a discourse on how a government and a society could and should function. After five long months of debate and endless compromise, the new Constitution, the new law for a new nation, was completed. We are not inclined to look at the Constitution as law, but of course it is. It is a system of law predicated on a written constitution—a novelty in the eighteenth-century world and indeed throughout much of recorded history. The new government would consist of three branches (executive, judicial, and legislative) and be a republic with limited suffrage, and it permitted enslavement of Africans or those of African descent. To ensure the application of the Constitution and future law created under it, Article III created a supreme court and other inferior courts as Congress saw fit to create.

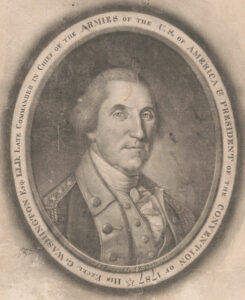

This mandate in the new Constitution was not lost on the first president, George Washington. The war hero turned politician would annotate his working copy of the Constitution indicating his duties and roles as president. President Washington would eventually appoint eleven justices and hundreds of lower court judges. He tried to follow a relatively simple criteria when looking for a jurist to nominate, writing to nominee William Paterson in 1793, “In performing this part of my duty, I think it necessary to select a person who is not only professionally qualified to discharge that important trust, but one who is known to the public and whose conduct meets their approbation.”[1]

Paramount among his duties was the selection of justices for the new supreme court and lower courts. This was not something President Washington took lightly. As with his general approach to life, he undertook his duties with precision and dedication. When considering the first six appointees for the Supreme Court (the number set for the original court per the 1789 Judiciary Act) Washington noted some criteria in a letter to William Fitzhugh on December 24, 1789: “in appointing persons to office, and more especially in the judicial department, my views have been much guided by those characters who have been conspicuous in their country.”[2] The six nominees Washington chose were indeed conspicuous: chief justice John Jay of New York, and associates John Rutledge of South Carolina, John Blair of Virginia, William Cushing of Massachusetts, James Wilson of Pennsylvania, and Robert Harrison of Maryland (Harrison withdrew from consideration and was replaced by James Iredell of North Carolina). All the president’s first six appointees were duly approved by the senate. Washington saw law as elemental to social and governmental function. He surmised to a colleague, “In assenting to the opinion that the due administration of justice is the strongest cement of good government, you will also agree with me that the first organization of the judicial department is essential to the happiness of our country.”[3]

Each of the three separate branches created by the Constitution, executive, legislative, and judicial, had to make their way with little guidance and no precedent. Each branch had to create its own rules and schedules. This was done expeditiously by all involved. When the new Supreme Court first met in February 1790, it had little judicial work to do and no cases before it. There were no disputes waiting when the justices arrived at the Royal Exchange building in New York at the foot of Broad Street. Ground rules and admission of lawyers occupied the first several days. The very first day three justices—Jay, Wilson, and Cushing—made their way to the court on time. All three were visually prepared for the moment, wearing attention-grabbing robes, and Cushing donning an English-inspired wig. That evening, the three justices dined with the president.

Several months after their appointments, President Washington shared his views on the state of law within the overall role of government in a letter to the justices, writing on April 3, 1790,

I have always been persuaded that the stability and success of the National Government, and consequently the happiness of the people of the United States, would depend in a considerable degree of the interpretations and execution of its laws.[4]

Until it adjourned for the year in August 1790, the court focused on “reading commissions, formulating rules, admitting lawyers to practice before it, and hearing a few motions.”[5] The first term of the supreme court ended somewhat anticlimactically.

Washington’s sense of the place of law within society came from a lifetime of lived experience. He never attended college or read law in preparation for a career at the bar. But growing up in mid-eighteenth century America as a planter ensured he was involved with the law on a regular basis. He saw the workings of colonial law as a mixture of English common law suffused with local variants. This mixing could be confusing for a planter with large commercial interests. Further, as the commanding general during the American Revolution he had seen firsthand the weakness of the American legal system and lack of uniform legal policy. These observations helped to strengthen his resolve when he became president. In fact, the turnover of personnel on the supreme court during Washington’s first term led him to lament, “the resignation of persons holding that high office, conveys to the public mind a want of stability in that department, where it is perhaps more essential than in any other.”[6] As concerned as he was about “the public mind,” President Washington was just as concerned with the international perceptions of the new American government.

The court’s second term began in February 1791 in Philadelphia after the move of the federal government from New York. The court took up residence in the new city hall building adjacent to the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). The first sitting of the second term began with no cases to attend to. The second meeting of the second term in August 1791 saw the first case arrive for the justices to hear. Nearly two years after the passage of the Judiciary Act the court was ready to do the most significant part of its job. West v. Barnes was heard on August 3, 1791.[7]

Similar to many of the early court’s cases during the Washington administrations, West v. Barnes dealt with disputes arising from the Revolutionary Era. This created problems as to authority and operation under different national systems. By default, pre- and Revolutionary cases sprang from the English common law system and were now being decided by a newly drafted Constitution for a newly created country. Further, mercantile debt had the added conundrum of English currency. In most instances, the early court ruled within narrow definitions of developing Constitutional law. In other words, the nation now absorbed the disputes churning for the past two or three decades that had lain unresolved. What was clear from the beginning was that the justices took their roles seriously and saw the Constitution as American law. The next case would emphasize this.

One of the most consequential cases to arrive before the court was not a case in the sense of a defendant and plaintiff. Rather, it involved separation of powers and the court asserting and acknowledging its independence. Hayburn began on March 23, 1792, when Congress passed the Invalid Pensions Act.[8] The Pension Act was crafted to provide financial support for Revolutionary War veterans and their families. Part of the process for claiming support under the act required pension seekers to appear before a federal circuit court to present their claim. The court would not judge in any way but simply gather the statement of the veteran or family member and forward the report to the secretary of war for processing.[9]

Before Hayburn appeared the justices of the northern circuit, Jay and Cushing, along with district judge James Duane, sent a letter to President Washington on April 5, 1792, explaining their concerns over the new requirement of the Pension Act. The two justices and judge argued “that enforcing the rules as written would violate separation of powers and judicial independence.”[10] The judges did not find the requirement to take the information a judicial duty. Nor did they approve of the requirement of having their work submitted to the secretary of war as the act mandated. Basically, the judges felt the work they were called upon to do to be beyond the functions of a judiciary. As it turned out, all six justices, sitting at their respective circuits, remarkably reached the same conclusion without consulting one another. This was institutional clarity from the justices so shortly after the court and nation was established. It was a precedent-setting determination that justices should not undertake extracurricular activities, nor could another branch review their work.

Congress and some justices were agitated by what we might call the optics of the case: “Although the arguments presented by the justices were legitimate, they do seem to miss the point of the humanitarian nature of the act and the need for some expediency for veterans and their families.”[11] The justices too were not unaware of the humanitarian nature of the work. And indeed, when congress revised the language, the new process by-passed the justices. The justices wrote, “by the Constitution, neither the Secretary of War, nor any other Executive official, nor even the Legislature, are authorized to sit as a Court of errors on the judicial acts and opinions of this Court.”[12]

Hayburn, and the resulting controversies, spawned spinoff cases. Chandler v. Secretary of War, and U.S. v Yale Todd would ultimately lead Congress to readjust the language of the Invalid Pensions Act in late 1792 and early 1793, removing the Supreme Court from the process. The assertion by the court of its prerogatives angered many in Congress. President Washington’s views are not preserved. Public sentiment seemed to side with the justices. The Philadelphia Independent Gazetteer wrote on April 21, 1792, that the justices “refused to take cognizance of his case … and looked on the law which imposes that duty, as an unconstitutional one, inasmuch as it directs the Secretary of War to state the mistakes of the Judges to Congress for their revision: they could not therefore accede to a regulation tending to render the Judiciary subject to the Legislature”[13] More emphatically the National Gazette wrote on April 16, 1792, “The late decision of the Judges of the United States, in the circuit court of Pennsylvania, declaring an act of the present session of Congress unconstitutional, must be [a] matter of high gratification to every republican and friend of liberty”[14]

President Washington’s role in shaping the contours of American law rightly deserve recognition. Although he wrote no legal treatises, nor did he study law, he ensured operational effectiveness was established and in place by the time he left office in 1797. Among the many precedents he established (really everything he did as president established a precedent) his commitment to the judicial branch has been equaled by few of his successors.

[1] George Washington to William Paterson, February 20, 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-16-02-0329.

[2] Washington to William Fitzhugh, December 24, 1789, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-04-02-0308.

[3] Washington to Thomas Johnson, September 28, 1789, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-04-02-0069.

[4] Washington to the Supreme Court, April 3, 1790, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-05-02-0201.

[5] Charles Grove Haines, The Role of the Supreme Court in American Government and Politics 1789-1835 (Reprint, Union, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, 2002), 123.

[6] Washington to Thomas Johnson, February 1, 1793, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-12-02-0053.

[7] The early supreme court bore little resemblance to what we are familiar with today. One obvious difference was the way cases were recorded. Somewhere around half of the early cases were not reported in any sense of legal thoroughness where the decisions could be relied upon in future cases as needed.

[8] The case acquired its name when veteran William Hayburn appeared before the middle circuit consisting of justices Blair and Wilson, and judge Richard Peters. The judges denied Hayburn a hearing, setting off a series of events.

[9] Supreme court justices, per the 1789 Judiciary Act were to ride circuit part of the year and were attending their respective circuits when the issue of Hayburn became widely known.

[10] Maeva Marcus, ed., The Documentary History of the Supreme Court of the United States, 1789-1800, Volume 6 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1992), 370.

[11] Jude M. Pfister, The Creation of American Law, John Jay, Oliver Ellsworth and the 1790s Supreme Court (Jefferson, MO: McFarland & Company, 2019), 145.

[12] Quoted in Maeva Marcus and Robert Teir, “Hayburn’s Case: A Misinterpretation of Precedent,” Wisconsin Law Review v. 527 (1988), 530.

[13] Footnote 2, James Madison to Henry Lee, April 15, 1792, founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-14-02-0259.

[14] Ibid.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...