George Washington’s confrontation with Maj. Gen. Charles Lee on a near hundred-degree afternoon, two miles west of Monmouth Courthouse on Sunday, June 28, 1778, ranks as one of the most iconic moments in battle during the Revolutionary War. It has been depicted in numerous paintings and sketches beginning in the 1800s, frequented Revolutionary War and George Washington literature throughout the 1900s, and within the past eight years alone it has been featured in four books and in a TV series (TURN: Washington’s Spies). No doubt it will be a highlight of the upcoming books and films.

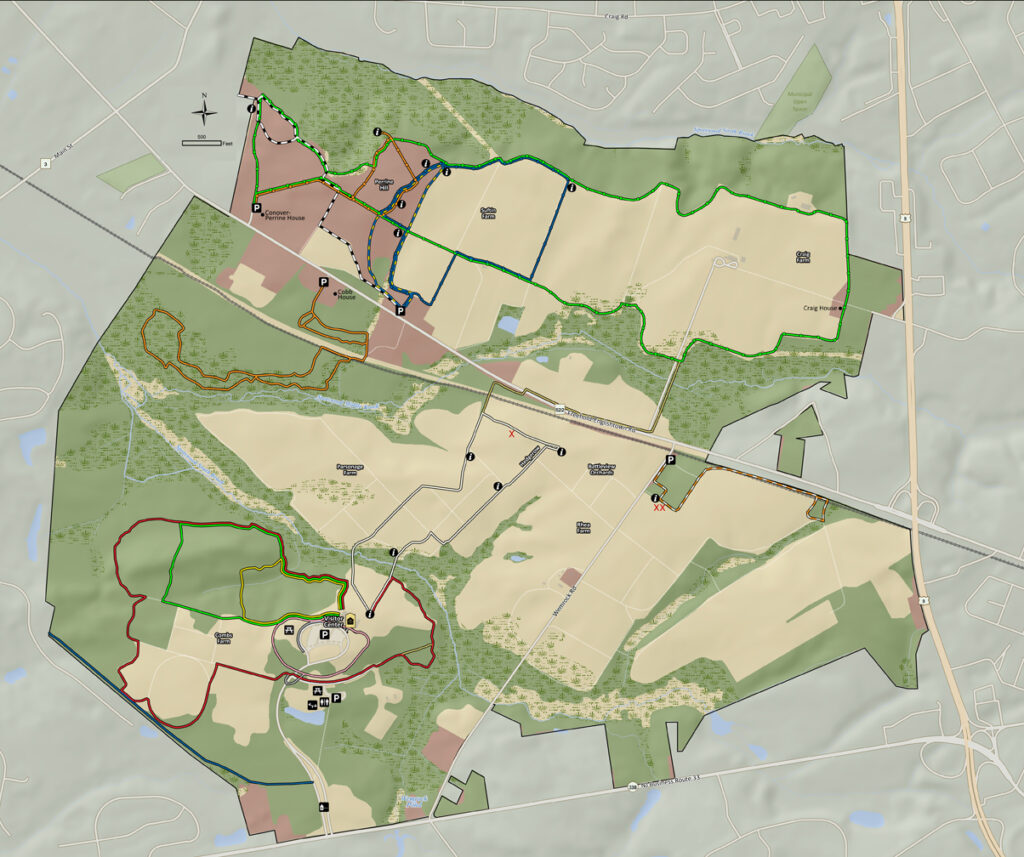

Despite the recent attention devoted to the confrontation, the five “W’s” (Who, What, When, Where, and Why) of this battlefield moment requires new attention because the primary sources describing this meeting are at odds with the traditional interpretation of it as well as the location in the Monmouth Battlefield State Park. The first-hand accounts also add meat to all of the recent books and filmography.

The following first-hand accounts are almost exclusively from the sworn testimonies of participants and witnesses in the court martial of Lee which began just six days after the battle and concluded a month later. These accounts are organized by each of the “W” questions.

Why did The Confrontation occur?

On the eve of battle, Charles Lee commanded an advanced corps in Englishtown, four miles in front of Washington’s reserve and five miles from the British forces aligned north and south of Monmouth Courthouse, prepared to march northward early the following morning. Washington instructed Lee in council, in written orders, and in follow-up verbal orders to attack the rearguard of the British army, which was three miles south of the courthouse, on Sunday morning, June 28. Each order was accompanied by the assurance that Washington would support Lee’s attack by moving the Grand Army up to the scene of conflict. For various reasons, Lee weakened Washington’s intended punch by adjusting the orders and departing Englishtown later than anticipated.

Washington’s Grand Army reached Englishtown before 9:00 A.M. on Sunday morning and found themselves just two miles behind the rear of Lee’s advanced corps, operating throughout the remainder of the morning on a theme of “3”s.[1] Advancing southeastward from Englishtown in a three-mile-long column on the Freehold Road, Lee’s progress was delayed further by three time-consuming halts which slowed their march to three hours to cover three miles toward the enemy retreating column. While Washington awaited the sound of Lee’s attack before moving to support, Lee consumed the final hours of the morning in a failed enveloping maneuver to surround the British rearguard, now one mile northwest of the courthouse, on three sides. The British countered with force which took advantage of isolated pockets of Americans, sending several thousand of them in retreat during Sunday’s noon hour.

Washington personally arrived on the field to witness his advance corps––containing more than 3,000 of his best trained and most experienced soldiers––retreating before his eyes, not in panic but still in mixed pockets of order and disorder and with no destination provided. Unable to ascertain who ordered the retreat or why, Washington sought high ground to look over the scene. From the crest of a hill, he and Lee caught sight of each other which led to Lee riding with at least three members of his staff to join up with the commander in chief on the knoll. According to Lee, he was more than satisfied with his generalship throughout the morning and maintained that “the troops [were] entitled to the highest honor; and that I myself . . . had merited some degree of applause from the General and from the public.”[2]

Washington could not disagree more with Lee’s self-assessment. This led to the confrontation on the hill.

When did The Confrontation occur?

Published histories place the time of the confrontation during the noon hour with, 12:45 most frequently settled upon in recent accounts.[3] It must have occurred later than this. We can time it based on Washington’s movements from Englishtown. His military secretary had completed a letter to the Continental Congress which he completed at 11:30 A.M., and a surviving document that indicates no sounds of battle had yet been detected; in fact, the letter reads as a lament from Washington that he anticipated the British would escape unscathed.[4] The sound of artillery fire reached Washington’s headquarters likely within minutes of the close of the letter. John Clark was west of Englishtown when he heard the artillery and doubled back to meet with Washington before the commander in chief sent him eastward to consult with Charles Lee.[5]

Based on these two reference points, Washington left Englishtown during the final fifteen minutes of the morning. Before the confrontation, Washington stopped at least twice, first at the Tennent Meetinghouse three miles from his Englishtown headquarters, where he met with Alexander Hamilton and Henry Knox who both returned from the front.[6] During this halt he sent a dispatch to Col. Daniel Morgan timed at 12:30 P.M.,[7] and he also decided to detach Nathanael Greene to collect his force to head to Combs Hill.[8]

The distance from the Tennent Meetinghouse to the confrontation site by Washington’s route was 1.6 miles. A reasonable departure from the Tennent Meetinghouse is 12:45 at the earliest and 1:00 P.M. at the latest. Halfway between these locales, Washington stopped again at the western morass on the battlefield, near the bridge that spanned Spotswood Middle Brook, to query and reposition retreating troops. This halt was briefer than the first one at the meetinghouse; regardless, the interlude stretched out the time required to cover the 2,800 yards to a minimum of fifteen minutes (and probably longer). Washington arrived first, with Lee joining him at least five minutes later. This convincingly pinpoints the Washington-Lee meeting after 1:00 P.M. and perhaps as late as 1:30 P.M. Splitting the difference yields an estimated time of the encounter between the two generals at 1:15 P.M.

Who was on the scene of the confrontation between Washington and Lee?

Seven members of the generals’ staffs are known witnesses to at least some of the verbal exchanges between the two generals. Three aides to Charles Lee accompanied him to the hill. Lt. Col. John Brooks, Lee’s adjutant, and Maj. John Mercer, Lee’s aide de camp, provided testimony to the confrontation. Another aide to Lee, Capt. Evan Edwards, indicated that with Lee, “We then rode on and met General Washington,” although Edwards did not report on what he saw or heard there.[9] From Washington’s staff, Lt. Col. Tench Tilghman and Lt. Col. James McHenry rode onto the height with Washington, where Lt. Col. Henry Kidder Meade joined them during mid-conversation. Alexander Hamilton was there in the immediate aftermath but does not appear to have been present during the interchange between the two generals.

A recent study of the battle effectively eliminates two oft-quoted “witnesses” to the confrontation, Brigadier General Charles Scott and Maj. Gen. Marquis de Lafayette, who likely were not in this region at that time.[10] The only other general-grade officer known to be present was John Cadwalader, a brigadier general of militia who accompanied Washington as a volunteer aide.[11] The presence of other personnel atop the hill is possible, but no documents confirm any besides these nine known participants and witnesses.

Where did the confrontation take place?

The primary sources strongly indicate that the confrontation site is not where it has been traditionally placed. It is within the Monmouth State Battlefield Park, but is more than 600 yards west of where the Wayside Exhibit signage east of Wemrock Road currently exists to interpret it. Several corroborating testimonies solidly place it atop what is now called “Oswald’s Knoll” after Lt. Col. Elezear Oswald of the Continental Artillery, a solitary hill nestled between the “Hedgerow” and “Parsonage Farm” sites in the park. (Today the knoll is a definite but unimpressive rise of land, the product of 250 years of erosion since the battle was waged.) Charles Lee’s defense testimony lays out the meeting site with one pre-confrontation hint and the rest of the evidence revealed after the verbal exchanges [12] [author’s emphasis italicized]:

Lee’s phrase “from this point of action until the eminence where we found General Washington” highlights a hill where he rode to Washington, and he did not ride alone.

Describing events after the confrontation, Lee said, “When [Washington] permitted me to reassume command on the hill we were then on, he gave me orders to defend it, in order to give him time to make dispositions of the army,” indicating that Washington left the hill and Lee stayed. Washington considered it a key point of defense.

Lee said, “The troops that remained on this hill were those that I intended should supply the place of General Maxwell’s brigade ordered before to cover the passage to this bridge. They were Stewart’s and Livingston’s battalions, and Varnum’s brigade.” The hill is near the bridge that spans Spotswood Middle Brook; Lee and three infantry units stayed at the hill. We know that two of them moved to the hedgerow at the eastern base of Oswald’s Knoll and Stewart moved up and to the left to join Wayne at Point of Woods.

Lee said, “But the moment I found his [Oswald’s] situation dangerous, I ordered him into the rear of Livingston’s again, which regiment, together with Varnum’s brigade . . . lined the fence that stretched across the open field. I here established a battery.” In this passage Lee clearly identified Oswald’s Knoll as the hill.

Further support for Oswald’s Knoll as the confrontation site can be found in the testimony of John Brooks, Lee’s adjutant:

I rode to the height upon which the principal action afterwards took place, upon where I found General Lee and some artillery, Varnums’s brigade, Livingston’s, and several other battalions. Upon asking General Lee his intention, he desired me to form those troops (pointing to Varnum’s brigade) as soon as possible. After having gone through the line, I observed General Washington rising the height, and General Lee riding to meet him. Just as they had met I came up with General Lee.[13]

Brooks has eliminated the unimpressive rise where the Wayside Markers for the confrontation exist today, since no “principle action afterwards took place” there. Instead, Brooks first rode up Oswald’s Knoll and saw Lee at the eastern base of it with troops identified with the hedgerow fight. He rode down to form Varnum’s brigade and then saw Washington ride up the same height he had just departed, then Brooks rode up again with Lee to meet Washington.

Brooks continued,

After this [the confrontation], General Washington left General Lee . . . General Washington returned and asked General Lee if he would command on that ground or not; if he [Lee] would, he [Washington] would return to the main body and have them form upon the next height. General Lee replied, that it was equal with him where he commanded[14]

This testimony gives stronger evidence that this was Oswald’s Knoll; Perrine Hill was “the next height” upon which Washington rode to form the main body. Lee stayed at the same height where the confrontation took place to oversee the hedgerow fight at the base.

Finally, the testimony of Major John Mercer, Lee’s aide, further supports Oswald’s Knoll as The Confrontation site with an account that closely matches Brooks:

When we first came up to General Washington I was close by General Lee, and heard the conversation that passed between them . . . [Mercer then discussed Washington leaving Lee and then returning] General Washington seeing General Lee, asked him if he would take the command there or he would . . . General Lee replied that [Washington’s] orders should be obeyed, and that he would not be the first to leave the field, and General Washington then rode to the main army.[15]

Mercer’s testimony closely mimics Brooks’ account, with Washington departing Lee twice, the second time ostensibly to head to Perrine Hill. Mercer did not yet identify Oswald’s Knoll as the confrontation, but the very next lines of his testimony seal this deal:

General Lee immediately ordered that the artillery should be brought to the height he was on, and begged General Knox, who was by, as he had a greater influence over them than had he. Colonel Livingston’s regiment was ordered up to support them.[16]

Knowing that Livingston’s men aligned at the hedgerow at the eastern base of Oswald’s Knoll, the unidentified artillery must have been Oswald’s. Therefore, “the height he was on” identifies Lee commanding from Oswald’s Knoll, the same hill on which the confrontation occurred.

Although the chronology varies between the testimonies of Lee, Brooks, and Mercer, together they provide an extremely powerful case to identify Oswald’s Knoll as the site of the confrontation between Washington and Lee. Furthermore, their testimony vanquishes the current location of the Wayside Exhibit markers (east of Wemrock Road) as a viable location for this encounter.

What happened during the confrontation?

Washington provided no commentary or testimony about what took place on the height. Charles Lee did, and his testimony was supported by witnesses from his staff and from Washington’s. As soon as Lee reached the crest, Washington rode across the height to confront him (Lee and one of his aides characterized it as “accosted”). Washington verbally rocked Lee the moment they were within speaking distance. “What is all this?” demanded the general.[17]

Caught completely off-guard, Lee could only stammer: “Sir? Sir?”[18]

Washington was hot. He repeated with growing anger, “What is the meaning of this? What is all this confusion for?” He demanded to know why his elite advance corps was in retreat. Washington’s force behind each question overwhelmed his second Lee: “The manner in which he expressed them was much stronger and more severe than the expressions themselves.”[19] His commander’s fury shook Lee to his senses. “When I recovered myself sufficiently,” recalled Lee, he rambled out a series of defensive explanations: he saw no confusion; General Scott did not follow his orders and “had quitted a very advantageous position;” Lee had also been deceived by contradictory intelligence, likely referring the enemy’s strength and position. James McHenry testified not recalling the exact words and phrases exchanged; however, “The manner . . . in which they were delivered, I remember pretty well; it was confused, and General Lee seemed under an embarrassment in giving the answer.”[20]

Lee regained confidence as he continued to explain what happened two miles east of that hill. After stressing to the general that the retreat “was contrary to my intentions, contrary to my orders, and contrary to my wishes,” he continued by defending his decision to let the mass retreat continue for two hours. Lee maintained to Washington, “I think, that had I remained longer in the situation I had been in, the risk so greatly overbalanced any advantages that could possibly have gained, that I thought it my duty to act as I have done.”[21]

Rather than be placated by Lee’s explanations, Washington pointedly told Lee that the enemy had not been considerable in his front while he was advancing, that Lee had encountered only a strong covering party.[22] Not included in most histories of their encounter is what, according to Lee, was said next by Washington: “There were some expressions (I cannot precisely recollect them) let fall by the General, which, at the instant, conveyed to me an idea that he adopted new sentiments, and that it was his wish to bring on a general engagement.”[23] Lee’s somewhat cryptic reference to expressions that Washington “let fall” was His Excellency repeating for the fourth time in twenty-four hours that he had planned to support Lee with the Grand Army––tell-tale evidence that Washington anticipated a large battle to develop––and that Lee should have held his advance position of contact rather than allow his troops to retreat from it.

It appears that Washington was willing to end the verbal exchange there, but Charles Lee attempted to impart the final say to reveal exactly where he stood on the battle plan and Washington’s campaign philosophy. In a sheepish-appearing explanation six weeks later, Lee simply said that Washington’s plan for a general engagement “drew from me some sentences.”[24] Four others on that hill during the second hour of Sunday afternoon heard Lee’s rebuttal. According to Tilghman, Lee told Washington “that he did not choose to beard the British army with troops in such a situation.” McHenry remembered, “General Lee said something at the same time of his being against the measure, but what measure it was I do not certainly know.”[25]

Lt. Col. John Brooks knew. As Lee’s adjutant he sidled next to him on the hilltop to hear Lee pontificate “that it was his private opinion that it was not for the interest of the army, or America, I can’t say which, to have a general action brought on, but notwithstanding was willing to obey his orders at all times, but in the situation he had been, he thought it by no means warrantable to bring on an action, or words to that effect.”[26] Henry Kidder Meade also knew. Having just arrived on the knoll, he “heard General Lee remind General Washington that he was averse to an attack or a general engagement . . . and I think I heard General Lee also tell General Washington that he was against it in Council, and that while the enemy were so superior in cavalry we could not oppose them.” Meade wasn’t the only one to claim Lee’s unusual position that dragoon superiority trumped larger bodies of trained infantry on a battlefield. According to James McHenry, Lee was adamant about this: “he there mentioned to his Excellency and some others that were round him, that effects such had happened to-day, would always be the consequence of a great superiority in cavalry.”[27]

Rather than burst into profanities, Washington replied with tact, a response remembered by several, and perhaps best expressed by Lee’s adjutant. John Brooks reported, “His Excellency showing considerable warmth, said, he was very sorry that General Lee undertook the command unless he meant to fight the enemy.”[28] Rather than vent his fury at Lee, Washington swallowed it and, according to Lee’s aide, simply but demonstrably “passed by him.”[29] With Tilghman, Cadwalader, McHenry and Meade in tow, Washington rode several hundred yards eastward from the knoll toward the point of woods to their left front.[30]

After the confrontation, Washington established three lines of defense: a forward (eastward) post at the Point of Woods commanded by Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne; the middle line at the Hedgerow and Oswald’s Knoll, superintended by Maj. Gen. Charles Lee; and the westward line of heights commanded at the southern end at Comb’s Hill by Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene, and at the northern end at Perrine Hill, led by Maj. Gen. Lord Stirling and where Washington himself personally superintended.

With afternoon temperatures approaching 100 degrees, the British eventually forced back the first two lines of American defense, but was unable to dislodge Washington’s men from the westward heights in an hours-long artillery duel marked by limited infantry clashes. In the end, Washington held Perrine Hill where his men enjoyed the exhilarating sight witnessed on several previous battlefields commanded by George Washington––redcoats turning their backs to retreat from the Americans.

The Battle of Monmouth was Washington’s sixth and final tactical victory as a battlefield general in the Revolutionary War.[31] This one was particularly special to the victors who commemorated it in a grand military pageant six days later, in an Independence Day celebration remembered proudly and fondly in pension applications half a century later. More than any other battle, Monmouth is marked by the mammoth moment when the commanding general “accosted” his second in command and subsequently turned a mass retreat into a victorious defensive stand.

[1] Time of arrival is estimated based on Washington’s departure at 7:00 A.M. from his encampment four miles northwest of Englishtown.

[2] Lee defense testimony, Proceedings of a General Court-Martial, Held at Brunswick, in the State of New Jersey … for the Trial of Major General Lee (New York, Privately printed, 1864), 217-18 (CLCMP).

[3] Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), 281; Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020), 142.

[4] George Washington to Henry Laurens, June 28, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0620.

[5] John Clark Statement, September 3, 1778, in Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1873, Volume 6 (New York: Printed for the Society, 1874), 231.

[6] Alexander Hamilton, Tench Tilghman and Henry Knox testimonies, CLCMP, 67, 91, 179.

[7] Washington to Daniel Morgan, June 28, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0626. Secretary Harrison routinely wrote the time on his letters in the headings, but he uniquely recorded it at the completion of them rather than the start of them.

[8] Robert H. Harrison testimony, CLCMP, 82.

[9] Evan Edwards testimony, CLCMP, 191.

[10] Lender and Stone, Fatal Sunday, 290.

[11] Tench Tilghman testimony, CLCMP, 94.

[12] Charles Lee defense, CLCMP, 215-216.

[13] John Brooks testimony, CLCMP, 168-169.

[14] Ibid.

[15] John Mercer testimony, CLCMP, 128-129.

[16] Ibid.

[17] John Mercer testimony, CLCMP, 128; Lee defense, CLCMP, 219.

[18] Tench Tilghman testimony, CLCMP, 93.

[19] Ibid.; Mercer testimony, CLCMP, 128; Lee defense, CLCMP, 219.

[20] Lee defense, CLCMP, 219; John Brooks testimony, CLCMP, 169; McHenry testimony, CLCMP, 90; Tench Tilghman testimony, 93.

[21] Lee defense, CLCMP, 219.

[22] Mercer testimony, CLCMP, 128-29.

[23] Lee defense, CLCMP, 220.

[24] Ibid.

[25] See testimonies of Meade, McHenry, Tilghman, and Brooks, CLCMP, 74, 90, 93, 169.

[26] Meade testimony, CLCMP, 74; Brooks testimony, CLCMP, 169.

[27] McHenry testimony, CLCMP, 90.

[28] Brooks testimony, CLCMP, 169.

[29] Mercer testimony, CLCMP, 129.

[30] Harrison Testimony, CLCMP, 86; Tilghman testimony, CLCMP, 93.

[31] Exclusive of the Siege of Yorktown. Washington personally commanded eleven battles from the summer of 1776 to the summer of 1778.

3 Comments

A great read! Well written and researched.

Gary, another terrific and original contribution. You make a compelling case about an interesting question over the years. It took me a while to spot on the map the tiny red Xs, but I found them. I am with you until the end of the article where you discuss the confrontation between Washington and Lee. You don’t mention that when Lee was on his way leading regiments to fight against the powerful advance of the British army also heading towards Monmouth village, he received reports that Brigadier Generals Charles Scott and William Maxwell had left the field without orders from him and without informing him. With more than half of his army gone from the field and his center totally exposed, Lee made the courageous but correct decision to retreat. As I explain in my article on this website regarding Scott’s fanciful story about Washington swearing at Lee during the confrontation, the soldiers Washington saw retreating were New Jersey Continentals from Maxwell’s Brigade who had just marched through the woods without being told by their commander why they were retreating!

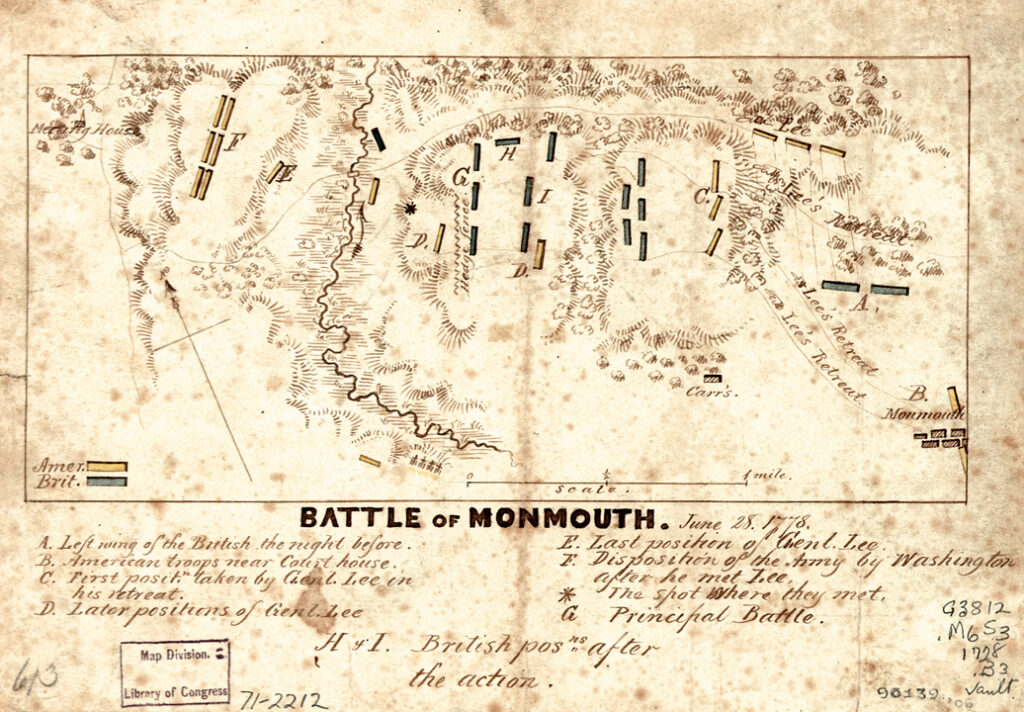

David & Christian, Thanks for your input. Visual evidence for the confrontation site can easily be seen in this 1778 map which places an asterisk on today’s “Oswald’s Hill” and labels it “the spot where they met”: https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3812m.ar128200/?r=0.09,0.203,0.856,0.356,0 [Ed.: This image has been added to the article.]

As for why I didn’t discuss what happened on the battlefield closer to Monmouth Courthouse, my article was only about the confrontation and was presented as a “Who, What, When, Where and Why” template. I simply had no room for a discussion of Lee’s performance. I plan to submit another article to JAR analyzing Charles Lee, but strictly as a field commander at Monmouth between 7:00 A.M. to 1:00 P.M. on June 28, 1778.