The court martial of Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, who had been George Washington’s second in command during the Monmouth campaign, centered on three charges against him for his conduct during the Battle of Monmouth, fought near Freehold, New Jersey, on June 28, 1778. Lee was found guilty by the court on all three charges. The first two charges have been analyzed with a strong and cogent defense of Lee in two recent book-length treatments of the campaign and Lee’s role in it.[1] Their explanation and analysis of the first charge—“For disobedience of orders, in not attacking the enemy on the 28th of June, agreeable to repeated instructions”[2]—has focused primarily on the troop movements and opening of battle during the morning hours (7:00 A.M. to the forenoon).

Testimonies in the Charles Lee court martial papers allow an updated analysis of that first charge. The following analysis highlights a council held the day before the battle and written instructions that followed half a day later. This detailed exploration of Washington’s instructions to Lee and Lee’s reaction to the orders is limited to his decisions before he left Englishtown for the Monmouth battlefield at 7:00 A.M. on June 28.

By late Saturday morning, June 27, the day before the Battle of Monmouth, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee commanded all the American troops within a six-mile radius of Monmouth Court House. The strength of his advanced corps approached 8,500 Continental and militia officers and men, primarily infantry but also including a few hundred artillerists and dragoons. Lee commanded more than 40 percent of Washington’s Grand Army in the region. Most of Lee’s corps was concentrated near Englishtown, five and a half miles by direct road west of the courthouse. The Englishtown force consisted of 5,000 “rank and file” Continental infantry (6,000 including commissioned and noncommissioned officers), as well as about 200 artillerists manning a dozen guns.[3]

In addition, Lee controlled detached forces closer to the enemy encampments. This included Col. Daniel Morgan’s command exceeding 1,000 Continental infantry–including five hundred picked men added five days earlier–four miles southeast of the courthouse, Col. Stephen Moylan’s dragoons, and about 1,300 New Jersey militia under Maj. Gen. Philemon Dickinson.[4] The latter two forces patrolled within observational distance of Gen. Henry Clinton’s Crown forces, 18,000 soldiers encamped along a five-mile stretch of a generally north-south road, the southernmost flank three miles below the courthouse.[5] Wary of Washington’s presence, Clinton prepared to march northward away from the region and toward New York early on Sunday morning, June 28.

The June 27 Council

The first time that battle instructions were discussed was a face-to-face meeting in Englishtown early Saturday afternoon, June 27 between Washington and Lee in a council with three brigadier generals: William Maxwell, Anthony Wayne, and Charles Scott. In the court martial, all three brigadiers testified as to what was discussed at this council. Although their testimonies vary, the common point made by all three, under oath, was that Washington sought a Sunday morning attack by Lee:

Scott: Washington “intended to have the enemy attacked the next morning . . . take the earliest opportunity to attack them.”[6]

Wayne: “fall upon some proper mode for attacking the enemy the next morning . . . General Lee was to attack the enemy.”[7]

Maxwell: “Lee was to attack the rear of the British army as soon as he had information that the front was in motion or marched off . . . by giving them a brisk charge by some of the best troops.”[8]

Typically the crucial role of attacking the enemy was given to the most senior officer, but two brigadiers concurred that Washington stressed otherwise on this occasion; although Maxwell was the senior brigadier general, his brigade was too top heavy in inexperienced troops (indeed, 573 had joined over the past seven weeks).[9] Washington delegated the specifics of the attack to his second in command, General Lee, and requested Lee hold a council with his generals later that afternoon at Lee’s quarters at the Davis Tavern about how to conduct the attack.

Lee indeed held that brief, late-afternoon meeting but decided against a specific plan, telling Maj. Gen. Marquis de Lafayette that he would “act according to circumstances” in the morning.[10] He simply reinforced Washington’s admonition about disregarding rank when the plan was put in motion. Often overlooked about Lee’s lax planning is Maxwell’s order from Lee to “keep in readiness in Englishtown to march at a moment’s warning, in case the enemy should march off.”[11] The gap between Lee’s force and Clinton’s rearguard was five and a half miles. At least two hours of marching was necessary to close the gap for an attack.

Written Attack Orders: “The Hamilton Letter”

Washington departed Englishtown after 5:00 P.M. and returned to his John Anderson house headquarters, four miles northwest of Lee. Several hours later and through the pen of his aide de camp, Lt. Col. Alexander Hamilton, Washington crafted a more specific attack plan for General Lee to follow. Testimony from both the Washington and Lee camps place the completion of these orders near midnight and their successful delivery to Lee between 1:00 and 2:00 A.M.[12] Based on preceding and subsequent events, a 1:15-1:30 delivery of the letter appears most reasonable, with scrutiny of it and reaction to it over the next fifteen minutes.

These are the only written orders detailing Lee’s intended role in the opening of the Battle of Monmouth. The document mysteriously—and suspiciously—disappeared within the next six days. Identified in court martial testimony as the “Hamilton Letter,” Washington’s orders within it were heavily discussed as evidence although the letter itself was never produced. Today, within the voluminous documents of the Charles Lee papers and elsewhere, this letter has yet to be found.

Fortunately, enough witnesses to the Hamilton Letter’s contents testified about it, allowing a credible reconstruction of its contents. Those witnesses include the two architects of the orders (Washington and Hamilton) and four recipients who read the letter: Charles Lee; his aide de camp, Maj. John Mercer; his adjutant general, Lt. Col. John Brooks; and Col. William Grayson, commanding a Virginia brigade. Another recipient, Capt. Evan Edwards, Lee’s other aide de camp, may have read a portion of the instructions, but his testimony appears based upon being informed immediately of its contents by General Lee. All others who commented on the letter are no better than hearsay documentarians; their claims are not considered here.

The two who wrote or spoke in the most general terms about the letter were the chief architect, Washington, and the chief recipient, Lee. Washington was not present at the court martial. His comments regarding Lee’s orders ae revealed in official and private correspondence. Those comments do not appear to separate verbal instructions to Lee and the three subordinates on June 27 from the letter penned by Hamilton. Regardless, Washington maintained that he ordered Lee “to begin the Attack next Morning, so as soon as the enemy began their march; to be supported by me.” He reported to Congress,

I determined to attack their Rear the moment they should get in motion from their present Ground. I communicated my intention to General Lee, and ordered him to make his disposition for the attack, and to keep his Troops constantly lying upon their Arms, to be in readiness at the shortest notice.[13]

Also only in generalities, Charles Lee testified in his defense that the content and circumstances “of Hamilton’s letter . . . have been sufficiently and clearly explained already.” A composite of all the sources of Washington’s plan (councils, written, and verbal orders) was distilled by Lee to:

it is necessary to make as clear as possible to the Court, the nature and spirit of the orders I received from His Excellency, at least to explain my idea of them . . . they were by no means precise and positive, but in a great measure discretionary, at least I conceived them as such.[14] (Emphasis added.)

Note the conflict between Washington’s and Lee’s interpretation of those orders. Where Washington claimed he specified a morning attack the moment enemy troops began to march away from Monmouth Court House with Lee’s troops ready to pounce upon that movement, Lee claims his orders were neither “precise” nor “positive.” This leaves the remaining four witnesses to reveal what was in the Hamilton Letter. They testified or wrote:

General Lee’s orders were, the moment he received the intelligence of the enemy’s march to persue them & to attack their rear.[15] [Hamilton to Elias Boudinot, July 5]

The order directed that General Lee should detach a party of 6 or 800 men to lie very near the enemy as a party of observation; in case of their moving off to give the earliest intelligence of it, and to skirmish with them so as to produce some delay, and give time for the rest of the troops to come up.[16] [Hamilton testimony]

It was an order for General Lee to detach about six or eight hundred men as a party of observation, who should march to within about two miles of the enemy, and there wait until the enemy began their march, and that this party should send continual intelligence, and should attack the enemy when they began to move, but this was left to the discretion of the officer commanding the party.[17] [Mercer testimony]

Lee received an order from His Excellency General Washington, for detaching six or eight hundred men to advance near the enemy, view their situation, give him frequent intelligence, and in case they retired to attack them.[18] [Brooks testimony]

one of General Lee’s Aides-de-Camp put into my hands a written paper from General Washington to General Lee, desiring him to send out about six or 800 men to act as a body of observation, and to give frequent information of the enemy’s movements, and to attack them in case they began to march. The next line, I think, was, that the time and opportunity was left to the commander of the party.[19] [Grayson testimony]

Few instances in the Revolutionary War provide such an impressive agreement between sources from opposing camps. These four independent testimonies repeatedly spell out one of the key components of the missing Hamilton Letter. Notwithstanding Lee’s claim to the contrary, these written orders were indeed, “precise and positive” regarding: 1) the number of troops to head the operation; 2) their initial destination within observational distance from the enemy; 3) an initiating “attack” and then “skirmish” by this force against the rear of the Crown forces column; 4) the attack timed at the start of the grand movement of Clinton’s army; and 5) discretion for the conduct of the attack granted not to General Lee, but to the officer commanding the six to eight hundred soldiers, as indicated by two of the four witnesses. What was still left to General Lee’s discretion was choosing the commander and the force to lead the attack. Per the previous afternoon’s council involving Maxwell, Wayne and Scott, Washington left the strong impression—although not absolute orders—that he preferred one of the picked veteran forces led by Scott or Wayne over Maxwell’s levy-heavy brigade.

One other important facet of the Hamilton Letter was revealed by the author and confirmed by one of Lee’s aides:

It also directed that [Lee] should write to Colonel Morgan, desiring him (in case of the enemy being on their march) to make an attack on them in such a manner as might also produce delay, and yet not so as to endanger a general rout of his party, and disqualify them from acting in concert with the other troops when a serious attack should be made.[20] [Hamilton testimony]

A letter was put into my hand . . . from Colonel Hamilton to General Lee, agreeable to the contents of which General Lee desired me to write to . . . Colonel Morgan . . .; the purport of what I wrote to Colonel Morgan, I think, was for him to advance with the troops under his command near the enemy, and to attack them on their first movement; it was left to his [Morgan’s] discretion how to act, only that he should take care not to expose his troops so much as to disable him from acting in conjunction with General Lee, if there was any necessity for it.[21] [Edwards testimony]

Again, near perfect corroboration was displayed from court martial witnesses diametrically opposed to each other in their support of Washington versus Lee.

It is clear that the Hamilton Letter ordered Lee to strike, in concert, from the west and/or south with his chosen Englishtown force and from the east with Morgan’s thousand-man corps against the rearward segment of Clinton’s army as it began to march northward. Discretion was stated for both Morgan and the commander of the force Lee would choose to initiate the attack from Englishtown. Implicit in the midnight composition and probable 1:30 A.M. delivery of the Hamilton Letter was the timely advance of the six to eight-hundred-man force so that it would be in a position to strike as the enemy began to march, which Washington expected to be at or near dawn’s first light (during the 4:00 A.M. hour) on Sunday, June 28. As Washington admitted to Hamilton, what prompted the midnight orders was his growing apprehension “that the enemy might move off either at night or very early in the morning, and get out of our reach, so that the purpose of the attack might be frustrated.”[22]

Charles Lee must have read that the discretion of Washington’s orders was left to the commanders of the two attacking forces. His personal discretion provided by Washington in front of the witnessing brigadier generals in the Saturday council was to choose the troops for the attack. Since the Hamilton Letter revealed that frequent observations were to be sent back to Lee regarding the disposition of the enemy rearguard, implicit discretion also was at Lee’s disposal to postpone or suspend the attack if that intelligence from the field bore overwhelming evidence that a change in enemy rearguard strength, location, or formation rendered the attack orders implausible.

Lee’s Actions on June 28

One would be hard pressed to name an example of a second-in-command general at any time in history who expected–let alone was ever granted–complete discretion to nullify his commanding general’s attack order the moment he received it, simply because he thought his own plan was better. But that is exactly what Lee did. As he explained in his trial defense, Lee considered Washington’s plan, “to spend the principle part of your force by an immediate attack on the rear of an army in retreats . . . is so absurd a scheme that it would be an affront to the Court to attempt demonstrating it.”[23] Without raising an objection and suggesting an alternative in the Saturday council or notifying Washington upon receiving the written orders, Lee immediately changed the plan. His subsequent decisions from 2 A.M. to 4 A.M. in Englishtown provide strong evidence that he disregarded the notion of an early morning attack in favor of a longer-developing alternative “of making an impression on both flanks,” a plan that consumed the rest of the morning hours without coming to fruition.

The dismantling of Washington’s verbal instructions and the dismissal of his written orders transpired before dawn. Lee’s aide de camp, Captain Edwards, followed Lee’s orders to craft and send dispatches to subordinate commanders. Edwards testified that he wrote orders to Maj. Gen. Philemon Dickinson in charge of 1,300 New Jersey militiamen to “select out about eight hundred of his best men, and to detach them as near the enemy’s rear as he could. These troops were to act as a corps of observation, and to forward the earliest intelligence to General Lee respecting the enemy.”[24]

Rather than sending 800 picked Continentals to first observe and then attack, Lee directed 800 militia to perform the observational duties highlighted in the Hamilton Letter—and gave no orders to attack. Lee made no modification to Washington’s orders for Morgan. Captain Edwards penned the attack order to Morgan: “to attack them at the same time on their right flank.”[25] Most encouraging about the orders to Morgan was that Lee did intend to attack sometime in the morning, but nowhere close to the time Washington ordered him to.

Edwards’s third missive (after Dickinson’s and Morgan’s) in the 2:00 A.M. hour was delivered to Lee’s chosen commander to lead the advanced corps out of Englishtown, a duty rightfully described by Lee’s headquarters as “a post of honor.”[26] Lee did not choose General Maxwell and his brigade, which upon first glance placated Washington’s intent from the June 27 council. But Lee also did not choose General Scott and his picked force of Continentals, nor General Wayne’s picked force of Continentals. Thus, none of the commanders that Washington met in council with Lee on Saturday, and briefly reconvened with Lee that same day, would spearhead the attack ordered by Washington.

Lee chose two brigades that were both demonstrably weakened by the Valley Forge experience, collectively losing 1,100 veterans who mostly had been discharged, but also had several deaths and some desertions during the six-month encampment, only to be replaced by half the number of levies who arrived early enough to be trained well but were still mostly new soldiers. In addition, there was a dearth of field officers in one of the brigades which “severely shocked their line,” as Washington wrote five weeks earlier.[27] Furthermore, no general commanded either brigade. The Virginia brigade chosen by Lee was normally commanded by General Scott; since Scott had transferred to lead a picked force, his brigade was led by its senior colonel, William Grayson. The other brigade was called Varnum’s brigade even though Gen. James Mitchell Varnum was currently absent from this force of Rhode Island and Connecticut troops. Col. John Durkee led this brigade that was not only reduced to half strength due to selected men sent to serve under Morgan, Scott, and Wayne,[28] but presumably left with a picked-over force consisting of lower quality veterans and top-heavy with new recruits. Two weeks earlier each brigade had encamped one thousand soldiers at Valley Forge,[29] but now no more than 1,500 officers and men were in both brigades combined. Nearly six hundred soldiers within those two brigades had never experienced battle before but were about to march out of Englishtown at “the post of honor,” ahead of the picked forces of several thousand experienced veterans and their equally experienced generals.

If gauged by the sum total of battle experience within the ranks, numerical strength, and proven quality of leadership, General Lee easily selected the weakest portion of his corps to inaugurate his plan. In an even more curious decision, Lee decided against putting either a major general like Lafayette–who was present and available–in charge of this two-brigade division, or transferring Brigadier General Scott, Wayne, or Maxwell to lead them. Instead, he reached within the two brigades and tagged Colonel Grayson to lead the would-be attackers for the battle of Monmouth on Sunday, June 28.

Washington, in the presence of Lee and the three brigadier generals, had pointedly expressed that forces swelled with inexperienced new recruits would be inferior for leading the attack. Maxwell remembered three weeks later that Washington intimated “that something might be done by giving them a very brisk charge by some of the best troops,” while Wayne testified that Washington “wished that the attack might be commenced by one of the picked corps, as it would probably give a happy impression.”[30] Why did Lee choose the two most suspect brigades to lead his troops out of Englishtown? Lee’s preference to not choose any of the three generals Washington expected to lead the attack, or a picked corps to open fire upon the British rearguard–and without a stated reason for those contrarian decisions–fell perfectly in line with Lee’s previous defiance of his superior’s wishes, dating back to the retreat from New York in the final weeks of 1776.

The conduct of Lee’s plan only got worse. Although Grayson’s command was chosen before 2:00 A.M., for reasons unknown an hour was lost getting the orders delivered to Grayson who encamped merely a few hundred yards west of Lee’s quarters. Grayson eventually led his 1,500 officers and men, with four 3-pound guns, into Englishtown. Captain Edwards claimed that Grayson’s command entered the town “about daylight” (near 4:00 A.M.); both Edwards and Grayson testified that Lee personally ordered Grayson “to march on about two or three miles, and then to halt.”[31]

Grayson revealed that Lee ordered him to simply to send back intelligence frequently as he obtained it; there was no order to attack. But within minutes of meeting Lee in Englishtown, Grayson did learn the complete mission—including Washington’s written orders to attack—from the Hamilton Letter, “which was put into my hands,” by one of Lee’s aides.[32] Now knowing he had the post of honor to initiate an attack, Grayson appropriately applied to General Lee for guides to lead his force toward the courthouse.

An hour later they continued to tarry in Englishtown because the guides Lee had ordered to be in place had disappeared from the village, forcing headquarters staff to hunt down a replacement. During this delay, a courier from General Dickinson delivered to Lee a missive announcing that they enemy had begun to move shortly after 4:00 A.M. Lee sent the messenger immediately on to General Washington. It was after 5:30 A. M. when an acceptable guide was available for Grayson.[33] Grayson set out shortly after with his two brigades in column on the Freehold Road on a planned three-mile march, at a cautious pace so that it was not expected to be completed until nearly 7:30 A.M. This would be three hours after dawn–and at least two hours later than what Washington’s written orders directed.

Almost immediately after Grayson’s departure, and before the rest of the Englishtown force aligned on the road to pass through Englishtown, a second express courier from General Dickinson found General Lee and informed him that the enemy had already advanced one and a half miles. Lee must have sensed that the delay in Englishtown was already costly. The enemy was marching away unmolested, and Grayson’s brigades were still at least ninety minutes behind them. Lee took this opportunity to attempt to correct his imprecise verbal order to Grayson to halt within three miles of the courthouse. According to Captain Edwards, “General Lee, from some intelligence, which I supposed he had received, sent me forward to order Colonel Grayson to push on as fast as possible and attack the enemy.”[34]

It must be emphasized that the witnesses from Lee’s staff provided critical testimony which ultimately painted Lee in this very unflattering light of indecision and poor preparation. This was unintentional on their individual and collective parts. Major Mercer, an aide-de-camp who gave one of four testimonies that Lee received a precise order to attack, was so dismayed by Lee’s subsequent conviction that he retired in protest. Edwards, the other aide, wrote rebuttals in newspapers to defend his superior against scathing newspaper attacks and served as Lee’s second in a duel.[35] Yet, Edwards’ testimony was particularly supportive of Hamilton’s remarks about Morgan’s intended role, and the sole source of evidence that Lee chose eight hundred militia rather than the “best men” Washington expected. Most revealing, Edwards’ testimony supported Grayson’s claim that Lee had initially sent Grayson out without orders to attack, before subsequently ordering him to do so.

In addition to amending Grayson’s instructions, Lee soon reversed another decision. Acknowledging in the court martial that “Colonel Grayson was only an officer of the line” who lacked experience and expertise when assessing terrain (no “opportunity of considering all its vices”), Lee halted the advance, called up General Wayne who was toward the rear with his picked force, and transferred him to the van to take over Grayson’s column.[36] This change of leadership cost Lee’s corps valuable time.

During the 7:00 A.M. hour, Lt. Col. Henry Kidder Meade, one of George Washington’s aides de camp, found Lee two miles southeast of Englishtown and delivered the verbal from Washington to Lee to attack–the third of the “repeated instructions” embodied in the first court martial charge. According to Meade:

I told him that General Washington had ordered the troops under his [Washington’s] command to be put in motion immediately, and that General Washington desired he [Lee] would bring on an engagement, or attack the enemy as soon as possible, unless some very powerful circumstances forbid it, and that General Washington would soon be up to his aid.[37]

From that moment onward, Lee did claim “very powerful circumstances” transpired throughout the remaining morning hours to allow the discretion granted to him; these events have been emphasized in modern histories of the trial and the battle. But those very powerful circumstances did not exist during Saturday’s council or during Sunday’s earliest hours when Lee received precise and positive written orders (as attested by four sworn witnesses) to “attack the enemy when they began to move.”

In his assessment a week after the battle, Alexander Hamilton ranted that Lee’s “conduct was monstrous and unpardonable.”[38] Hamilton’s statement is hyperbolic but the “unpardonable” tag appears most apt regarding Charles Lee during his single-day sojourn in Englishtown. Lee dismissed Washington’s instructions and orders for a near-dawn attack and replaced it with his own drawn-out plan to envelop the British rearguard from three directions—“this plan,” Lee confessed with candor, “was defeated, and I had no longer hopes of success.”[39] He never asked permission to make or execute this plan; he never informed the commander in chief that he intended to disregard written orders. Orders given to Lee did not afford this degree of discretion to immediately dismiss them in Englishtown, prior to any of his troops entering the battlefield where changing circumstances did allow it.

Charles Lee did indeed disobey Washington’s precise, positive, and repeated instructions to attack the enemy “in case they began to march” on June 28 in favor of his own plan which subsequently failed. His immediate dismissal of the written orders from his superior alone renders him guilty of the first court martial charge leveled against him.

[1]Christian McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis: The Outrageous Treason and Unfair Court-Martial of Major General Charles Lee during the Revolutionary War (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020); Mark Edward Lender and Garry Wheeler Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2016).

[2]Proceedings of a General Court Martial, . . . for the Trial of Major General Lee (Philadelphia: John Dunlap, 1778), 2.

[3]Alexander Hamilton testimony, ibid., 57; Anthony Wayne testimony, ibid., 22.

[4]Philemon Dickinson to George Washington, June 23, 1778, in Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 30 volumes (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1985 -), 15:510-511 (PGW). Dickinson noted his force was “12 or 1300 Privates,” making a total force including officers at 1300 a very reasonable but minimalist estimate. General Orders, June 22, 1778, PGW15:493.

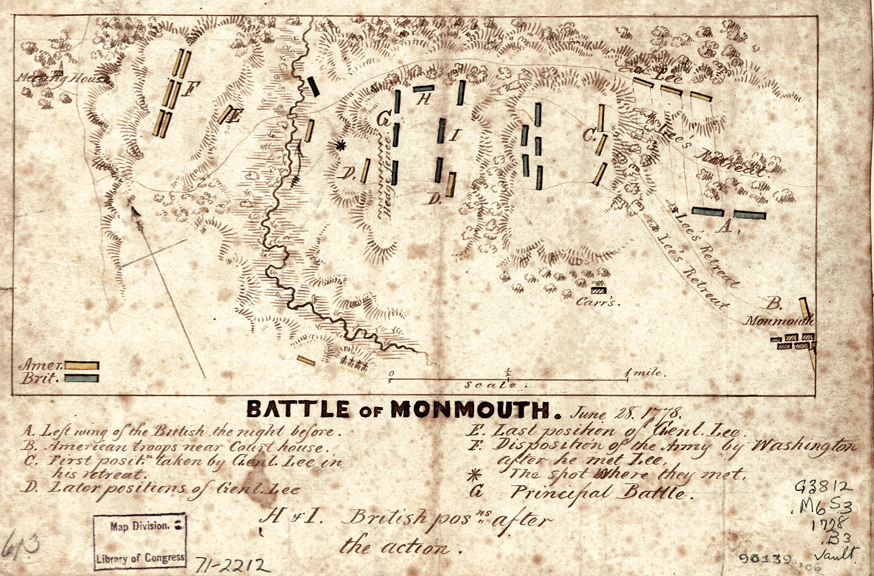

[5]Lender, Fatal Sunday, 185. Gary Wheelers Stone’s map on this page indicates the position of the opposing forces on June 27, except for Dickinson’s militia and Moylan’s cavalry.

[6]Wayne testimony, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 4-5.

[7]Charles Scott testimony, ibid., 2-3

[8]William Maxwell testimony, ibid., 89.

[9]“New Jersey Brigade Tally for Joining from May to August 1778,” www.scribd.com/doc/216378254/The-Action-was-renew-d-with-a-very-warm-Canonade-New-Jersey-Officer-s-Diary-21-June-1777-to-31-August-1778.

[10]Marquis de Lafayette testimony, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 11.

[11]Maxwell testimony, ibid., 89; Charles Lee defense, ibid., 176.

[12]Hamilton, John Mercer and Evan Edwards testimony, ibid., 9.

[13]Washington to John Augustine Washington, July 4, 1778, PGW16:25; Washington to Henry Laurens, July 1, 1778, ibid., 2-7.

[14]Charles Lee defense, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 175-176.

[15]Hamilton to Elias Boudinot, July 5, 1778, in Harold C. Syrett, ed., The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 1, 1768-1778(New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 510-514.

[16]Hamilton testimony, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 8-9.

[17]Mercer testimony, ibid., 102.

[18]John Brooks testimony, ibid., 143.

[19]William Grayson testimony, ibid., 34.

[20]Hamilton testimony, ibid., 9.

[21]Edwards testimony, ibid., 161.

[22]Hamilton testimony, ibid., 8.

[24]Edwards testimony, ibid., 161

[25]Daniel Morgan letter, June 29, 1778, ibid., 120.

[26]Wayne testimony, ibid., 17-18.

[27]Washington to Patrick Henry, May 23, 1778, PGW, 15:200.

[28]Lender, Fatal Sunday, 189.

[29]William S. Stryker, The Battle of Monmouth (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1927), 277.

[30]See testimonies of Scott, Wayne, and Maxwell in Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 2-5, 89.

[31]Edwards testimony, ibid., 161-162; William Grayson testimony, ibid., 34

[32]Grayson testimony, ibid., 34.

[33]Grayson testimony, Edwards testimony, Mercer testimony, ibid., 34, 102-103, 161-162. Dickinson to Washington, June 28, 1778, PGW, 15:577. Lt. Col. John Brooks, Lee’s adjutant, timed Grayson’s departure from Englishtown at “about six o’clock.” Brooks testimony, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 143. Based on the timeline of subsequent events, his claim appears reasonable.

[34]Edwards testimony, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 162; David Forman to Washington, June 28, 1778, PGW, 15:577.

[35]Lender, Fatal Sunday, 401; Francis Heitman, Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army During the War of the Revolution(Washington, DC: n.p., 1893), 164, 291; McBurney, George Washington’s Nemesis, 261.

[36]Lee defense, Proceedings of a General Court Martial,185; Wayne testimony, ibid., 17-18.

[37]Henry K. Meade testimony, ibid., 7-8.

[38]Hamilton to Boudinot, July 5, 1778, The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, Vol. 1,510-514.

[39]Lee defense, Proceedings of a General Court Martial, 198.

Cite this Article

Ecelbarger, Gary. “Did Charles Lee Disobey George Washington’s Attack Order at Monmouth? Journal of the American Revolution, https://allthingsliberty.com/2024/03/did-charles-lee-…rder-at-monmouth/

4 Comments

Gary, congratulations on an amazing article. I think it has some of the most original material of all the All Things Liberty articles. With your inquiring mind and careful research, you have created a whole new line of inquiry about the Battle of Monmouth. That is saying something, given the battle was almost 250 years ago. However, I disagree with your conclusion that Lee was guilty of not not following orders to attack. That being said, given the material you present, I agree that reasonable minds could differ, which is a credit to your work. Your findings on Lee from the date of his meeting with Washington on June 27 to 7 am on June 28 shows very disturbing behavior by Lee. I agree that Lee was on a path to disobeying orders to attack. But then he corrected himself. His path was not a straight one. After receiving the Hamilton orders at about 1 am, he timely issued orders for Grayson to immediately form and march to the enemy. And he issued orders for the rest of his detachment for form behind Grayson. I don’t think Lee can be blamed for two inadvertent issues resulting in 3 hours of delay in Grayson forming and marching, including Grayson’s efforts to find a local guide. Yes, Lee could have done better in finding a local guide earlier, but many generals did worse than that in battles and were not court-martialed. Lee also saved himself by issuing the order to Grayson to attack the enemy prior to Grayson reaching the enemy. Therefore, I do not believe he was guilty of not attacking the enemy by 7 am. Later in the day he issued orders to attack the enemy and made plans to attack the enemy, and he even marched with Grayson’s brigade to fight the enemy converging at Monmouth Courthouse. But when Lee learned that 40% of his detachment, troops under Generals Scott and Maxwell, disappeared from the battlefield without informing Lee and without orders. Lee made the painful but correct decision to retreat. He then later organized the defense at the Hedgerow, which saw fierce fighting along with the ambush at the Point of Woods, thus giving time for Washington’s main army to establish a strong defensive position.

In addition, it is strange that Washington, in his after battle reports, never mentioned this timeframe as being a problem; and Hamilton, who wrote the order, in his testimony at the court-martial and letters after the battle, did not mention this timeframe as being when Lee failed to follow orders to attack the enemy. Moreover, observers then and historians now have thought that the mild penalty imposed on Lee–suspension from the army for one year–was because the court-martial judges thought Lee was really only guilty of the third charge in disrespecting the commander-in-chief by his two letters to Washington after the battle.

Your focus on Lee having Grayson take the lead as opposed to Scott or Maxwell is interesting. I wonder if Lee did not want to have the glory of making the attack go to Scott or Maxwell, who were both strong supporters of Washington. But I don’t believe that Lee going with Grayson meant that he was guilty of not obeying orders to attack the enemy. He timely ordered Grayson to attack the enemy.

I must also add that Washington’s idea of having 800 or so Continentals rush out in advance of Lee’s detachment and attack the rear of the enemy’s army if the rear began to march away and if an opportunity presented itself was a very poor plan. I believe the rear of the army was on Lee’s side of the ravine and had about 2,000 men in the camp. So the idea of 800 men attacking 2,000 was dubious. The attackers would have been at the time of the attack entirely unsupported; they would have had to retreat immediately and try to meet up with the rest of the detachment. It reminds me of Mark Lender emphasizing that Washington wanted to do “something” to prove to Congress and the people that all the investment and training of his Continental army at Valley Forge was worth it. But this plan shows how desperate Washington was. In addition, I think there was zero chance that Morgan’s men could have assisted in a coordinated attack on the rear of the enemy. Morgan was more than two miles away and had no idea where the rear of the enemy was located. It was nighttime and he could not have known when and where an attack could have been made. The attack on the rear likely would have taken no more than 20 minutes and the attackers would have had to have retreat immediately. Morgan could have attacked somewhere else; but he did not do that on the day of the battle.

In any event, congrats again on an incredible piece and opening up a new area of controversy!

Christian,

Thanks for the accolade. Keep in mind, I don’t claim Lee disobeyed orders to attack in general; I tried to demonstrate that he pointedly disobeyed Washington’s written orders immediately after receiving them and rewrote them to fit his own plan. I know of no precedent where a subordinate is allowed that kind of discretion to dismiss written orders simply because he didn’t like the plan — a plan he voiced no objection to when it was outlined during the previous day’s face-to-face council. Choosing not to follow a superior’s written orders for a near-dawn attack with specifics provided on the size and location of the assaulting forces is the definition of insubordination, isn’t it?

Speaking of the council, Grayson wasn’t invited because it was obvious with 2 brigades of elite picked troops within Lee’s command, Washington could never fathom Lee even considering disregarding either of them in favor the least experienced brigades to lead the rest out of Englishtown. The plan did not call for an attack by 800 attacking 2,000 as you assert; it called for an attack by 1,800–Morgan’s picked force of 1,000 officers and men was specifically ordered to strike from Richmond Mills against the right flank. The key was to hit it on both flanks right when it started moving near dawn. This would place the dual attacks southwest of the courthouse where the British rearguard encamped that night. It would have been in open ground without a morass or other impeding terrain features–when Clinton would actually have been surprised by a strike against even one of his rearward flanks, let alone both of them in a dual strike. That opportunity disappeared at 2:00 A.M. when Lee decided his plan was better. (It obviously wasn’t.)

Gary and Christian, I thoroughly enjoyed reading your back-and-forth on Lee’s behavior before and during the Monmouth Battle. With the benefit of hindsight and your analyses, the most significant issue for me is not bringing Daniel Morgan’s command into the battle. Morgan’s unit should have been the eyes and ears of the Continental vanguard and fixed the British in battle as it performed during the Saratoga campaign. A timely flanking attack by Morgan’s corps could have made a big difference. Gary, you believe Lee did not give Morgan proper, unambiguous orders. While this appears true, the failure to incorporate Morgan’s command into the battle plan seems to be the most egregious error for which, in my view, Lee, Washington, and Morgan all have some culpability.

Gary: On your first point, I agree with you that Lee was on the path you describe. But he did timely order Grayson to march to the enemy around 1:30 a.m., and if Grayson had not experienced his two delays, he would have likely arrived in time before the British rear guard moved off. And Lee did have an order delivered to Grayson to attack the enemy prior to Grayson reaching the enemy. I think those are the two most important factors and therefore I am not seeing Lee being properly convicted of not attacking the enemy by 7 am. On your second point, I stick by my belief that there was zero chance that Morgan would have been able to coordinate with Grayson on an attack on the British rear guard. He and his men were more than two miles away. Once Grayson arrived at the enemy’s camp, he would have had to have attacked immediately or not all. If he did attack immediately, the attack likely would have been over in about twenty minutes and then Grayson and his troops would have had to have high-tailed it back to the rest of Lee’s detachment. This would not have provided Morgan any material time to march to join in Grayson’s attack–Morgan had no idea where the rear guard was, it was nighttime, and he was more than an hour away in marching time. Also Morgan’s orders were to attack the enemy’s flank (not rear). There was no order that was more specific asking Morgan to coordinate his attack with another force. I guess we will agree to disagree! But your new material has made the issue one where reasonable people could disagree.