Poet Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-1784) was a consistent and passionate advocate for liberty in every form: she called for an end to slavery, championed political and religious freedoms, and considered a sinful life to be a kind of servitude. She consistently opposed British infringements on American rights and saw political oppression as a form of slavery. Wheatley was surrounded by other proponents of liberty and human rights, but here we will see her penchant for freedom through the prism of her attendance at the radical Old South Church (at a building now called the Old South Meeting House) and her self-proclaimed, special devotion to Reverend Joseph Sewall (1688-1769), who was her mentor and who passionately backed American freedoms.

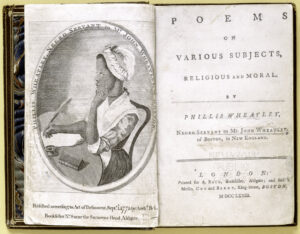

Wheatley’s life was remarkable. Born in about 1753 on the west coast of Africa, she was enslaved there as a child, transported to the New World, and sold to the family of Boston tailor and merchant John Wheatley (1703-1778). The Wheatleys recognized young Phillis’s facility with language and helped her to develop her literary talents. Wheatley was the first African American to publish a book and was one of the earliest women in the thirteen colonies to publish a book on any subject. After a successful literary trip to London and the publication of her verses in 1773, Wheatley garnered considerable attention. John Wheatley granted Phillis freedom from bondage in September or October 1773, but times were difficult in Boston for the next decade, even after the British evacuation of the city. Wheatley went on to marry (1778, to a John Peters) and have children, but never published another book of verses, and she died at the age of thirty one, having recently been working as a seamstress and a maid in a boarding house.

Phillis, like members of the Wheatley family, attended Congregational meetings. In particular, she received significant tutelage from Rev. Joseph Sewall, who was a pastor of the Old South Church for fifty-six years beginning in 1713.[1] Phillis would have known him at the end of his time as minister, between her ages of nine and sixteen or so. Phillis had extensive contact with Sewall, and in a poem of homage upon his death described how she heard his “warnings and advice.” She called him “my monitor,” a spiritual guardian and mentor who gave her ideas and watched over her moral development. Wheatley was particularly learned, and Sewall may well have offered her access to the substantial library at the church. We have no records of their personal conversations, prayers together, or which sermons she heard, but we know that she heeded his advice that her “monitor” was a consistent and passionate advocate of civil and religious freedoms. After his death in 1769, the congregation became ever more openly rebellious as troubles intensified with Britain.

Sewall was part of a distinguished Massachusetts family. He was the son of Samuel Sewall (1652-1730), perhaps most famous to us for his role as a judge at the Salem Witch Trials. In light of Joseph’s later interactions with Miss Wheatley, it is noteworthy that Samuel Sewall wrote the first known treatise in America supporting abolition, in 1700: The Selling of Joseph. He argued that “it is most certain that all Men, as they are the Sons of Adam, are Coheirs; and have equal Right unto Liberty.” Addressing the Old Testament account of how Joseph’s brothers sold him into slavery in Egypt, Samuel wrote:

Yet through the Indulgence of GOD to our First Parents after the Fall, the outward Estate of all and every of the Children, remains the same, as to one another. So that Originally, and Naturally, there is no such thing as Slavery. Joseph was rightfully no more a Slave to his Brethren, then [sic] they were to him.[2]

The judge wrote in his diary that he named his son Joseph “in hopes of the accomplishment of the Prophecy, Ezek. 37th and such like: and not out of respect to any Relation, or other person, except the first Joseph.” Thus, he named him after the Joseph in Genesis who was sold into slavery, rose to become a political leader in Egypt, and under whose name Ezekiel was prophesied to revive Israel.[3] There is no explicit record about Joseph Sewall’s attitude toward abolition, and the minister might not have wanted to take a public stance on a controversial topic, but it is likely that he was sympathetic to the idea, as were some other Congregational ministers and churchgoers in Boston. Noteworthy is his father’s abolitionist stance and Joseph Sewall’s awareness that his very name was a reminder of the illegitimacy of slavery.

Joseph Sewall favored the downtrodden, and a contemporary noted that Sewall felt deeply for the plight of Native Americans: according to the published obituary of 1769 by Congregational minister Charles Chauncy (1705-1787), Sewall’s “heart was strongly touched with pity towards” the “INDIAN natives.”[4] To be sure, Joseph Sewall was well-prepared to interact in a sympathetic way with Wheatley. And it is a fitting capstone to the family’s anti-slavery history that Joseph Sewall’s great-grandsons Samuel Edmund Sewall (1799-1888) and Samuel Joseph May (1797-1871), both Bostonians and Harvard graduates, became fervent abolitionists and collaborators of William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879).

As Phillis Wheatley would have known well, Joseph Sewall was a champion of both religious and political freedoms. The Congregational Sewall especially deplored the longstanding and continuing infringements by the British upon religious rights, such as the proposals to appoint an Anglican bishop over the colonies, and he opposed their political impositions such as taxation and the stationing of troops in Boston. His last years comprised the distressing time of the Stamp Act (1765), Declaratory Act (1766), and the Townshend Acts (1767-1768). Chauncy again on Sewall:

He was a strenuous asserter of our civil and ecclesiastical CHARTER-RIGHTS and PRIVILEDGES. He knew the value of them.—He knew they were the purchase of our fore-fathers at the expence of much labor, blood, and treasure.—He could not bear the thought of their being wrested out of our hands.[5]

An anonymous obituary echoed Chauncy, also stressing Sewall’s abhorrence of British infringements both religious and civil and noting how the reverend spoke passionately about such issues:

He was greatly alarmed with every motion to introduce the Hierarchy into these Colonies, whose predecessors had, at the peril of every earthly comfort, fled from the face of ecclesiastical tyranny. Nor was he less jealous of the attempts made to deprive us of our civil liberties … These things lay with weight on his mind as long as he lived, he spake with freedom, and some degree of warmth, on this interesting topic.[6]

Chauncy accurately summarized Sewall’s belief in American exceptionalism and his opposition to British curtailment of religious liberties, which he saw as linked to civil liberty. In a sermon of 1724, and quoting Increase Mather (1639-1723), Sewall thundered before the “Lieutenant Governor and the Council of Representatives of the Province of Massachusetts Bay” that “the Principal Design upon which these Colonies were at first Planted, was to Profess, & Practice & Enjoy, with undisturbed Liberty, the Holy Religion of GOD our Saviour.”[7] Phillis Wheatley’s pastor would speak with “some degree of warmth” on such topics, and she was schooled in the ideology that the colonies needed “undisturbed liberty” to establish the right, holy kind of government that was not possible in the Old World.

When Sewall died in 1769 of a paralytic stroke at the age of eighty one, Wheatley joined the widespread celebrations of his life by writing a poem, which exists in several manuscript variants in addition to the version (cited here) that she published in 1773 in her book of verses. The first lines include a reminiscence of his sermons and conversations ringing in her ears: “Hail, holy man, arriv’d th’ immortal shore, / Though we shall hear they warning voice no more.”[8]

Sewall seemed to have a special interest in addressing youth like Wheatley:

Mourn him ye youth, to whom he oft has told

God’s gracious wonder from the times of old.

I, too have cause this mighty loss to mourn,

For he my monitor will not return.[9]

Rightly sensing the religious foundation for the thought and poetry of Wheatley, whose poems are indeed infused with theological ideas, Thomas Jefferson (1740-1826) said of her (misspelling her first and last names) that “religion has indeed made a Phyllis Whately.”[10] Others have noticed that her poems, which were, after all, subtitled in 1773 as “religious and moral,” are often exhortations like sermons.[11] Wheatley did not attend any formal schooling, and she seemed to get many of her ideas and sense of things from the fiery Calvinist preaching that she heard from the likes of her “monitor” Joseph Sewall, among others. She often managed to insert lines into her poems that touched on freedom, and in her poem to Sewall she inserted the Calvinist statement that the kind of “grace divine” that Sewall felt in his life is what “rescues sinners from the chains of guilt,” a line that suggestively equates living in sin with chattel slavery.

Following her early exposure to Sewall and other ministers and congregants there, Phillis Wheatley became an official member of the church upon reaching adulthood (August 1771). Sewall’s and Wheatley’s house of worship remained a well-known hotbed of the American Revolution through the 1770s, the place later nicknamed the “Sanctuary of Freedom.” The firebrand politician and brilliant agitator Samuel Adams (1722-1803) was a notable member of the congregation of Old South Church. Crowded meetings happened there in 1770, a year of tumult over taxation and the large-scale British military occupation of the city. For a meeting on the day after the Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770), of a group too numerous to gather in Faneuil Hall, people were still, a year after Sewall’s death, associating the building with him: on March 6, 1770, members “Voted that this Meeting be adjourned to Dr. Sewalls Meeting House.”[12] Most famously, patriots convened at the Old South Meeting House at various meetings from November 29 until December 16, 1773, with the tumultuous gathering on this last day occurring just before the Boston Tea Party.[13] Phillis Wheatley, by then a free woman, must certainly have been interested in the dramatic events at her church. The Sons of Liberty, ready for action and further stirred up by the words of Samuel Adams, dressed as Indians and emerged from “Sewall’s Meeting House” with war whoops and headed to Boston Harbor to deal with the unwanted tea.

Other Congregational churches in Boston gave strong support to the American cause, including the vigorously pro-patriot First Church, under Charles Chauncy, and the New South Church, where Phillis’s owners, John and Susanna Wheatley (1709-1774), attended. Knowing the political positions of the congregation and the leaders of the Old South Church, in October 1775 the occupying British troops cleared out most of the woodwork inside and turned the large interior of the Old South Meeting House into an open space for equestrian and other military training (the pews and other woodwork there now date from the mid-nineteenth century and later).

Wheatley was schooled in freedom by her monitor, Joseph Sewall, and came to see that civic and religious freedoms are desirable and linked. Sewall was hardly promoting religious pluralism, and was most concerned that the British, with their established state religion, would refrain from suppressing American Congregational churches in any way. Still, his way of thinking intersected well with the wider calls for political and personal liberty that were the foundation of the American Revolution. At any rate, Wheatley’s idea of freedom was broader than Sewall’s. A special focus of her love of liberty, going beyond ideas that Sewall might have shared but not expressed, centered on abolition. Numerous poems and letters from Wheatley’s hand decried chattel servitude, and she linked opposition to slavery with the struggle against all political oppressions, including British tyranny over the thirteen colonies. Calling political oppression slavery or bondage was widespread among other American revolutionary writers, but the linkage is especially compelling coming from Wheatley, who experienced enslavement first hand and who (unlike many American agitators) was an actual and open abolitionist.

Wheatley published her book of verses in London in 1773 with the support of William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth (1731-1801), and she dedicated verses to her patron in which she described tyranny over America as like bondage in irons:

No more, America, in mournful strain

Of wrongs, and grievance unredress’d complain,

No longer shall thou dread the iron chain,

Which wanton Tyranny with lawless hand

Had made, and with it meant t’ enslave the land.[14]

Wheatley added that her own enslavement gave her a keen sense of the burdens of slavery, and she wanted others never to feel the oppressions of bondage:

Should you, my lord, while you peruse my song,

Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung,

Whence flow these wishes for the common good,

By feeling hearts alone best understood,

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent’s breast?

Steel’d was that soul and by no misery mov’d

That from a father seiz’d his babe belov’d:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway?

Another remarkable document indicating Wheatley’s holistic idea of liberty — freedom from slavery, from religious persecution, and from political oppression and violation of one’s natural rights — is a letter she wrote to Rev. Samson Occom (1723-1792), a Native American, Presbyterian preacher in Connecticut. This important missive of February 11, 1774 was shared with the world, being published in the next few months in a number of American newspapers, including The Massachusetts Spy, the Connecticut Gazette, and (cited here) The Connecticut Journal. She declared that God has implanted in us a love of freedom. As a preacher might do, she linked this important idea with a biblical story, saying that we pant for deliverance from oppression as the Israelites had done during their captivity in Egypt:

I have this Day received your obliging kind Epistle, and am greatly satisfied with your Reasons respecting the Negroes, and think highly reasonable what you offer in Vindication of their natural Rights: Those that invade them cannot be insensible that the divine Light is chasing away the thick Darkness which broods over the Land of Africa; and the Chaos which has reign’d so long, is converting into beautiful Order, and reveals more and more clearly, the glorious Dispensation of civil and religious Liberty, which are so inseparably Limited, that there is little or no Enjoyment of one Without the other: Otherwise, perhaps, the Israelites had been less solicitous for their Freedom from Egyptian slavery; I do not say they would have been contented without it, by no means, for in every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our modern Egyptians I will assert, that the same Principle lives in us … How well the Cry for Liberty, and the reverse Disposition for the exercise of oppressive Power over others agree, I humbly think it does not require the Penetration of a Philosopher to determine.[15]

She interpolated here the challenging and extraordinary statement that slaveholders in America were now the “modern Egyptians.”

Wheatley, like many others in Boston, had the gratification of seeing the armed struggle for independence underway. She supported that effort, and, at the same time, was savvy and needed a hit poem, and she found the perfect subject in George Washington, the hero of the day in Massachusetts. Typical of her background and thinking, in her “To His Excellency General Washington” she highlighted the moral essence of Washington’s virtues, describing him as “fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more,” and noting that he led the hopes of a nation:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! be thine.[16]

She wrote a poem about him in the Fall of 1775 and sent it to him in the hopes that it would find its way to publication. Wheatley wrote to him in a respectful way:

SIR, I Have taken the freedom to address your Excellency in the enclosed poem, and entreat your acceptance, though I am not insensible of its inaccuracies. Your being appointed by the Grand Continental Congress to be Generalissimo of the armies of North America, together with the fame of your virtues, excite sensations not easy to suppress … Wishing your Excellency all possible success in the great cause you are so generously engaged in. I am, Your Excellency’s most obedient humble servant, Phillis Wheatley.[17]

Washington had misplaced her letter, and wrote to her on February 28, 1776. It is noteworthy that he took the time to write while anxiously awaiting arrival of the cannons from Fort Ticonderoga and writing just one day after a false alarm that the British were attacking Dorchester Heights, as he alluded to in his letter to her. On March 4 he triumphantly installed the cannons there.[18]

Washington’s letter to Wheatley was genteel and personal. He praised her “genius” as a poet and, in a personal touch, he even confessed his fears to her that the public might consider him self-promoting if he openly arranged to publish the letter:

Mrs Phillis,

Your favour of the 26th of October did not reach my hands ’till the middle of December. Time enough, you will say, to have given an answer ere this. Granted. But a variety of important occurrences, continually interposing to distract the mind and withdraw the attention, I hope will apologize for the delay, and plead my excuse for the seeming, but not real, neglect.

I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents. In honour of which, and as a tribute justly due to you, I would have published the Poem, had I not been apprehensive, that, while I only meant to give the World this new instance of your genius, I might have incurred the imputation of Vanity. This, and nothing else, determined me not to give it place in the public Prints.

If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favourd by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations. I am, with great Respect, Your obedt humble servant, G. Washington.[19]

That Wheatley visited Washington at headquarters is attested to by one late source: Benson J. Lossing (1813-1891), who was perhaps passing along oral information, and who put a the time of her visit as mid-March 1776:

Washington invited her to visit him at Cambridge, which she did a few days before the British evacuated Boston; her master, among others, having left the city by permission, and retired, with his family, to Chelsea. She passed half an hour with the commander-in-chief, from whom and his officers she received marked attention.[20]

As he stated, Washington did not want to appear vainglorious by arranging for its publication of the poem, but others, like his aide-de-camp Joseph Reed (1741-1785) did the job for him: the poem appeared on the front page of the Virginia Gazette on March 30, 1776 and again, in the next month, in The Pennsylvania Magazine in Philadelphia, a publication headed by editor Thomas Paine (1737-1809).[21]

Wheatley’s dealings with Washington were extraordinary, but so was her whole life. She lived as a slave and a colonial subject, but finished her years as a free citizen in an independent republic. All along, Phillis Wheatley’s writings and life were deeply enmeshed in the world of revolutionary Boston. As emphasized here, she was brought up in the world of Joseph Sewall, and, as Jefferson rightly noted, religion shaped her thought. Wheatley wrote about liberty from her teenage years onward, but she did not have long to experience peace time and the fruits of American independence. She died on December 5, 1784, less than a year after Washington resigned his commission in Annapolis. Two years after her death, the first American edition of her poetry came out.[22] Her name has never been forgotten, and a vast field of literary and historical scholarship about her life and works flourishes today.[23]

[1] There is extensive information on Joseph Sewall’s activities and leadership at the Old South Church in Benjamin Wisner, The History of the Old South Church in Boston, in Four Sermons (Boston: Crocker & Brewster, 1830). See also Hamilton Andrew Hill, The Reverend Joseph Sewall: His Youth and Early Manhood (Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1892); and Clifford K. Shipton, Sibley’s Harvard Graduates, Volume V – 1701-1712 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1937), 376-393.

[2] Samuel Sewall, The Selling of Joseph (Boston: Bartholomew Green and John Allen, 1700), 1.

[3] The Diary of Samuel Sewall, 1674-1729, 2 vols, M. Halsey Thomas, ed. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), 1973), vol. 1:175, August 19, 1688.

[4] Charles Chauncy, Discourse Occasioned by the Death of the Reverend Dr. Joseph Sewall (Boston: Kneeland and Adams, 1769), n. p.

[5] Ibid., n. p.

[6] From an Appendix in the Boston Evening-Post, July 3, 1769.

[7] Joseph Sewall, Rulers must be Just, Ruling in the Fear of GOD (Boston: Printed by B. Green, 1724), 27.

[8] “On The Death of The Rev. Dr. Sewell. 1769,” in Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (London: A. Bell, 1773), 19. Modern editions of her poems include Julian D. Mason Jr, ed., The Poems of Phillis Wheatley (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989); and William H. Robinson, ed., Phillis Wheatley and her Writings (New York and London: Garland Publishing, 1984).

[9] Wheatley, Poems, 21.

[10] Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia (London: Printed for John Stockdale, 1787), 234. His observations about Wheatley are not found in earlier editions of his book.

[11] See, for example, Paula Loscocco, Phillis Wheatley’s Miltonic Poetics (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 58-59.

[12] Unsigned, Freedom and the Old South Meeting-House (Boston: Directors of the Old South work, 1910), 12.

[13] “Minutes of the Tea Meetings, 1773,” Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, vol. 20 (1882): 10-17.

[14] Wheatley, Poems, “To the Right Honourable WILLIAM, Earl of Dartmouth,” 74. She also received support for the publication from Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (1707-1791).

[15] Phillis Wheatley to Samson Occom, The Connecticut Journal and the New-Haven Post-Boy, April 1, 1774, front page. See also Robinson, ed., Phillis Wheatley, 332.

[16] Phillis Wheatley to George Washington, October 26, 1775, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 2 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2008), 242.

[17] Ibid, 242. See also The Writings of Phillis Wheatley, Vincent Carretta, ed. (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 131.

[18] Washington to Artemas Ward, February 27, 1776, ibid., 3:384: “We were falsely Alarmed a while ago with an Acct of the Regulars coming over from the Castle to Dorchester … w[oul]d it not be prudent to keep Six or Eight trusty men by way of Lookouts or Patrols to Night on the point next the Castle as well as on Nuke Hill. At the same time ordering particular Regimts to be ready to March at a Moments warning to the Heights of Dorchester; For should the Enemy get Possession of those Hills before us they would render it a difficult task to dispossess them—better it is therefore to prevent than remedy an evil.”

[19] George Washington to Phillis Wheatley, February 28, 1776, ibid., 3:387.

[20] Benson J. Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, 2 vols. (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1860), 1:556.

[21] Published in the “Poetical Essays” section of The Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Monthly Museum, vol. 2 (April 1776), 193.

[22] Phillis Wheatley, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (Philadelphia: Joseph Cruikshank, 1786).

[23] Recent studies, with further bibliography, include Vincent Carretta, Phillis Wheatley Peters: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2011, and a new, updated edition of 2023); and David Waldstreicher, The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley: A Poet’s Journeys through American Slavery and Independence (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2023).

One thought on “Champions of Liberty: Phillis Wheatley, Joseph Sewall, and the Old South Church”

Dr. Manca, regarding Phillis Wheatley…

(My old notes – partial timeline)

On January 1, 1772, a slave named PHILIS, submitted a poem called “Recollections” to the London Magazine.

On 23rd June 1772, the Universal Magazine carried this report:

“The Court of King’s Bench gave judgment in the case of Somerset the Negro, finding that Mr. Stuart, his master, had no Power to compel him on board a ship, or to send him back to the Plantations; but that the owner might bring an action of trover against any one who shall take the Black into his service. A Great number of Blacks were in Westminster – hall, to hear the determination of the cause, and went away greatly pleased.”

The London Chronicle published an anonymous letter attributed to Franklin; it ran from Thursday, June 18th through Saturday, June 20th:

“It is said that some generous humane persons subscribed to the expence of obtaining liberty by law for Somerset the Negro. — It is to be wished that the same humanity may extend itself among numbers; if not to the procuring liberty for those that remain in our Colonies, at least to obtain a law for abolishing the African commerce in Slaves, and declaring the children of present Slaves free after they become of age. By a late computation made in America, it appears that there are now eight hundred and fifty thousand Negroes in the English Islands and Colonies; and that the yearly importation is about one hundred thousand, of which number about one third perish by the gaol distemper on the passage, and in the sickness called the seasoning before they are set to labour. The remnant makes up the deficiencies continually occurring among the main body of those unhappy people, through the distempers occasioned by excessive labour, bad nourishment, uncomfortable accommodation, and broken spirits. Can sweetening our tea, &c. with sugar, be a circumstance of such absolute necessity? Can the petty pleasure thence arising to the taste, compensate for so much misery produced among our fellow creatures, and such a constant butchery of the human species by this pestilential detestable traffic in the bodies and souls of men? — Pharisaical Britain! to pride thyself in setting free a single Slave that happens to land on thy coasts, while thy Merchants in all thy ports are encouraged by thy laws to continue a commerce whereby so many hundreds of thousands are dragged into a slavery that can scarce be said to end with their lives, since it is entailed on their posterity!” – The London Chronicle 20 June 1772.

It is unknown (to me) whether Phillis Wheatley had any knowledge of the Somerset cause.

“BOSTON, May 10. 1773. Saturday last Capt. Caless sailed for London, in whom went Passengers Mr. Nathaniel Wheatley, Merchant; also Phillis, the extraordinary Negro Poet, Servant to Mr. John Wheatley. FAREWELL to AMERICA. To Mrs. S____ W_______ By Phillis Wheatley. [After the poem]: It was mentioned in our last that Phillis the Negro Poet, had taken her passage for England, in consequence of an Invitation from the Countess of Huntington, which was a mistake.”

“BOSTON, September 20. 1773 In Capt. Caless, from London, came passengers Capt. Hillhouse and Lady. Mr. Aleing; also Phillis, the extraordinary poetical Genius, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley, of this Town.” (Boston Evening Post.; Date: 09-20-1773; Issue: 1982; Page: [2])

My implication is that “poetical Genius” Wheatley’s path to freedom had a basis in the Somerset case and may have been “by design.”

NOTE: Dr. Franklin mingled with Granville Sharp and Dr. John Fothergill while in England during the Somerset trial. He was already well acquainted with Anthony Benezet of Philadelphia; meanwhile John Adams of Boston had already been reading a 1771 publication from Sharp & Benezet, as well another 1767 anti-slavery publication.

Sharp also corresponded with abolitionists Selina, Countess of Huntington, Anthony Benezet, (& latter Dr. Rush). It is unknown if Franklin attended the Somerset proceedings, but upon his 1774 return to America he carried 250 copies of “Declaration of the Rights of the People to a Share in the Legislature” written by Sharp.

The Reverend George Whitefield, was pro-slavery but also sought compassion for the Negroes and he ran an Orphanage in Georgia. He was also the minister to the Countess of Huntington. When he died in September 1770, Phillis Wheatley published a poem honoring him; while the Countess inherited the Georgia Orphanage.