In 1902, the new owner of a furnished house in Medford, Massachusetts, was rummaging through the accoutrements and amenities of his recent acquisition. John O’Callaghan then noticed a box with an unusual inscription: “Here’s our family flag from the war.”

Intrigued, O’Callaghan opened the container and found a frayed flag. As he unfolded the red, white and blue banner, he realized it had far fewer stars than the then-current flag’s forty-five. He counted the handstitched five-pointed celestial symbols and was excited by the total: thirteen. Had the home’s new owner discovered an original Revolutionary War flag?

Since 1976, O’Callaghan’s great grandson, James Mooney of Cincinnati, has been on a quest to determine the authenticity of his family’s flag. Over the years, he has collected a considerable cache of evidence for the claim, including identifying a descendant of the person from whom O’Callaghan bought the house in Medford. “It was a nice home, fully furnished, that was bought from a widow,” Mooney says. “Her husband’s family had fought in the Revolutionary War. In that house in a box was that flag.”

The elderly widow was Mrs. Manfred Earl Nichols. Her husband was related to William Ayers, who served in the Revolutionary War at a fort on Castle Island in Boston in 1783. Back then, it was known as Fort Adams (renamed Fort Independence in 1799).

It is believed that Ayer was one of the men responsible for flying American flags at the fort, including a large one (it measures about 106 by 67 inches) that is in secure storage at the Massachusetts State House in Boston. According to tradition, that flag was sewn in 1781 by Jonathan Fowle of Jamaica Plain and flown over the fort, where the maker’s son George served as a Ranger. It was donated to the state in 1903 by his son, George W. Fowle.

“The donation of the flag was documented in the Boston Post when it was given,” says State House Curator Susan Greendyke. “It was preserved backwards by the conservator in the 1920s. We don’t know why but it might have had something to do with the stars looking better.”

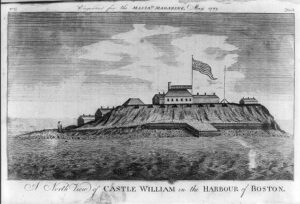

A famous etching in the May 1789 issue of the Massachusetts Magazine shows a large thirteen-star flag flying over “Castle William,” as the fort was originally called by the British. A second pole without a flag is depicted in the engraving. Might that be where the Mooney Flag flew some 240 years ago?

In style and construction, the found flag bears a striking resemblance to the Fort Independence Flag, also known as the Fowle Flag. Though noticeably smaller, the Mooney Flag – measuring approximately 28 by 55 inches—features seven horizontal red stripes and six white, along with the distinctive thirteen white stars on a blue background. Those stars are arrayed in the 4-5-4 pattern (three rows of four, five and four stars) typical of American flags from the late eighteenth century.

According to Mooney, his family’s flag remained in storage until about the 1940s, when his grandfather gently cleaned it in a tub of water with a mild soap. Unfortunately, the original container with the writing identifying the flag is gone now. “My mom told me more than a few times how my great-grandfather opened up the box, took the flag out, and discarded the box,” Mooney recalls. “People didn’t collect things for their value as much back then as they do now.”

No one thought much of the flag until just before the nation’s bicentennial in 1976, when Mooney’s mother, Mary, suggested they protect it and display it. By that time, the family and flag were located in the Cincinnati area. “My mother said, ‘You know, we got this old flag. We should probably do something with it.’” At great expense, the family had the flag cleaned and preserved to museum quality. It was carefully mounted on a cloth backing and then encased in a glass and wood frame to keep it safe from the elements. It was reframed in 2007.

Over the years, Mooney was obsessed with learning more about his family’s flag. Genealogical research led to the discovery of the connection between the Medford homeowner’s husband and Ayer, the Revolutionary War soldier stationed at the Boston Harbor fort.

Part of the concern about the Mooney Flag being authentic was the fact that countless thirteen-star flags were produced in 1826 to commemorate the country’s fiftieth anniversary. Could this flag be a replica from that era? Those concerns were laid to rest after Mooney consulted with several experts, all of whom verified that the style, textiles and dyes used in his flag were consistent with those used in the late eighteenth century.

“I found the best forensic textile expert in the entire country, Dr. Rabbit Goody,” Mooney says. “She knows everything about textiles. She has been hired by museums, including the Smithsonian, to figure out if fabrics were appropriate for a certain timeframe. She’s also a historian on flags and banners.” From her studio and manufacturing facility in the Finger Lakes region of New York, Goody examined the Mooney flag and concluded it “could have been produced during the time period 1770 and 1790.”

Her 2001 report goes on to say: “The irregularities in the yarn, the irregularities in the weaving and the sewing techniques used in this flag are consistent with the fabrics of the eighteenth century. . . . I found no areas which I felt were problematic or inconsistent with eighteenth century fabrics or flag construction in the last quarter of the eighteenth century.”

In a telephone interview, Goody reaffirmed she has little doubt in the flag’s authenticity. Though not the oldest, she strongly believes it dates to the Revolutionary War. “I’d say in a very good position with all the other thirteen-star flags we have identified,” she states. “It sits in really good company.”

According to Mooney, Goody’s assessment was confirmed by a second textile expert, the late Dr. Irene Good of Harvard University’s Peabody Museum, as well as by researchers at the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage in Belgium.

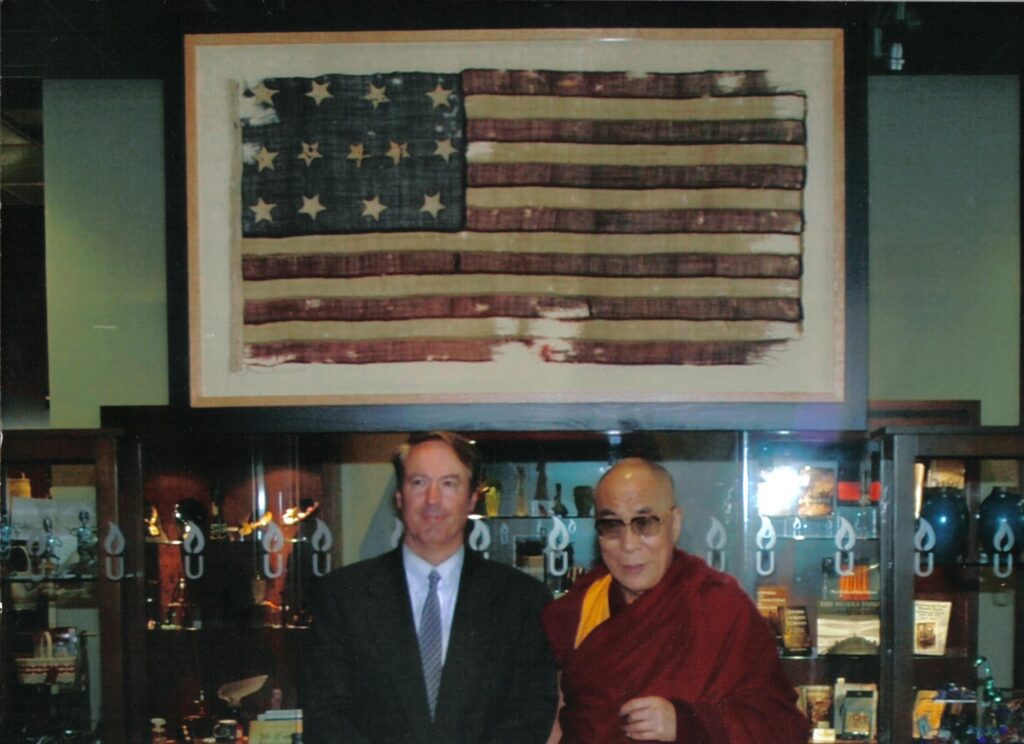

For several years, the Mooney Flag was exhibited at Flag City in Findlay, Ohio, where thousands of visitors viewed it. It was also shown at other museums and historic sites around the country. In 2007, the flag was on exhibit at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati. One day, a famous visitor stopped by to view the museum’s collection: the Dalai Lama of Tibet. Mooney decided to show him the flag. Though told not to speak with or touch his holiness, Mooney struck up a conversation and told him the history of his family’s flag.

“He was very impressed and asked me a question or two,” Mooney recalls. “I had my photo taken with him and the flag. Then, I wrapped my arm around his back, tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Thanks a lot. Nice to meet you,’ and shook his hand. That was probably getting a little too familiar.”

Since 2016, the Mooney Flag has been on loan to the Commonwealth Museum in Boston. Strategically positioned in the lobby, it is the first artifact seen by visitors as they enter the museum, which is also home to the Massachusetts State Archives. Mooney believes his mother, who was the driving force for enabling the public to view the flag, would be proud. “My mother (who died in 2013) was an extreme patriot,” he says. “She was very proud of the flag. She took it to heart that this was an artifact of great importance. She wanted to make sure it was protected and shared for everyone to see.”

Recent Articles

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...