Ten days before General Daniel Morgan’s momentous victory at Cowpens, a battle, or rather to some, a skirmish took place beyond the peripherals of the Continental army on the Eastern Seaboard. Though all but forgotten by the majority of history books and locals, this action was the bloodiest Revolutionary War battle fought in modern-day Alabama and was quite possibly the key fulcrum of a power struggle in the vast colony of West Florida.

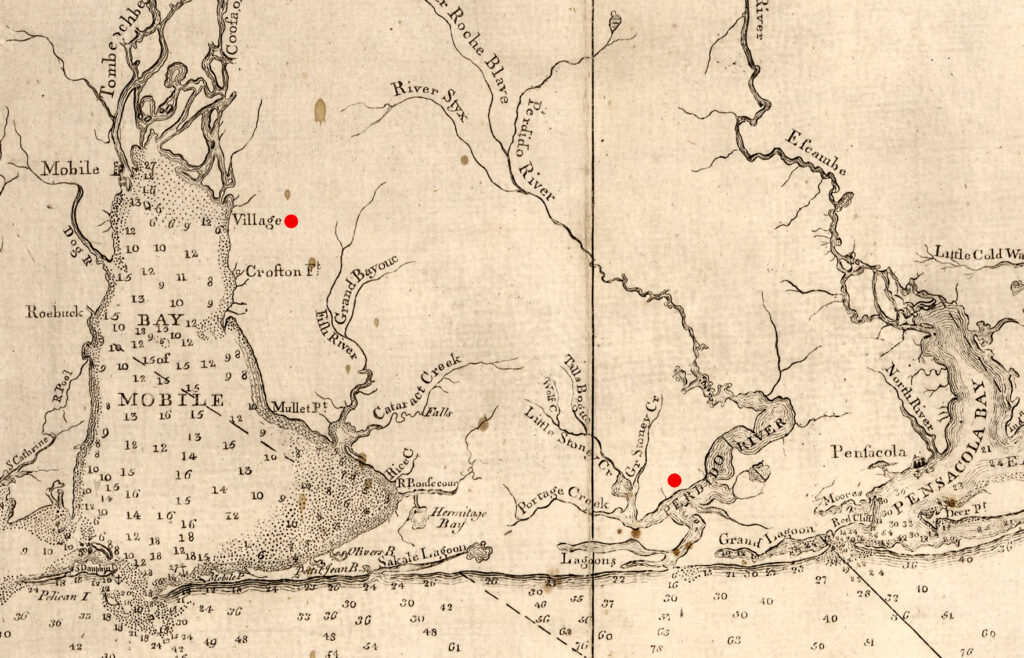

Stretching from the Mississippi to the Apalachicola Rivers, West Florida had been a hotbed for conflict since Spain declared war on King George III in May 1779. Bernardo de Gálvez soon commenced successful sieges against the British forces at Baton Rouge in September 1779 and Mobile in March of the following year. Following the capitulation of Fort Charlotte at Mobile on March 14, 1780, Maj. Gen. John Campbell soon found his headquarters at the capitol city of Pensacola, just slightly over fifty miles away, to be within striking range of the Spanish. The disputed territory between these cities, modern-day Baldwin County, Alabama and Escambia County, Florida, would then become the primary battlefront of the Gulf Coast campaign for the next fifteen months.

For the most part, this area at the time was nothing short of an uninhabitable wilderness dangerous to any person that set foot on its land. Aside from the few communities and plantations that existed on Mobile Bay and its tributary rivers, there were almost no settlements in the region. While there existed a road between Pensacola and Mobile, it was one that was heavily mired with thickets, felled trees, washouts, and depending on the weather, sometimes impassible creek crossings.[1] Along with these, wild predators were a constant source of danger.[2] Raids carried out by Native Americans and partisans were a prevalent threat to both Spanish and British outposts, and particularly to vulnerable civilians. These conditions would heavily weigh on the operations and combatants that played out within the area.

While the frontier straddled the Perdido River, the most important location within this territory was the self-referentially named The Village. The largest settlement on the Eastern shore of Mobile Bay at the time, The Village (also known as La Aldea or the Village of Mobile) commanded an imperative strategic position in West Florida as it was the primary waypoint for the Pensacola-Mobile Road to cross Mobile Bay. Surrounding the community on the bayfront was a string of large plantations owned by prominent English West Florida officials such as Attorney General Edmund Wegg and Lieutenant Governor Elias Durnford, the commander who surrendered Fort Charlotte. These plantations, along with smaller nearby French communities, were raided by Native Americans on numerous occasions for their cattle, horses, slaves, or other valuables during the area’s tenure as the seat of war. As The Village was under threat of this constant raiding from Great Britain’s native allies, Spanish military officials deemed it necessary to establish a fortified post protecting it.[3] With this position under guard, the Spanish could control a clear avenue to cross Mobile Bay, create a base for forward operating posts in the Perdido region, and protect valuable cattle and drinking water resources.[4] This was indeed necessary as the community was directly attacked at least four times while under Spanish control during the war.[5]

The most coordinated and vigorous of these attacks occurred in January 1781. As General Campbell sought a foothold to retake Mobile and its surrounding communities, he ordered a joint naval and ground offensive to take the post at The Village. While sources vary on the exact number of troops in the attacking force, it contained approximately 180 to 200 regulars and militia, and 300 to 500 Native Americans (precisely counted at 420), totaling a force as high as 700.[6] Supporting this force were two brass 3-pounder field cannons.[7]

General Campbell sought to overwhelm his adversaries with superior numbers, but starkly underestimated the Spanish forces at the post to be around 100 troops, possibly due to outdated intelligence.[8] The 190-strong Spanish force defended the redoubt at the time of the attack.[9] The fortification was described as consisting of a series of entrenchments, wooden and earthen palisades, and a central stockade with an officers’ quarters.[10] Much of the structures were apparently somewhat dilapidated.[11] It was quadrangular with moats on all sides except that which faced the bay. A “serpent’s tongue” (a narrow, external fortification that jutted out) was also constructed. The fort was located nearby the ferry and anchorage area.[12] Within and surrounding the fortification were the encampments of troops and militia. At the time of the attack, it was supplemented with two 4-pounder cannons.[13]

While the two opposing forces fought for the Spanish and British Empires, they would both represent prime examples of the diverse groups that participated in the American Revolution. Needing every able-bodied man in the Louisiana colony, Governor Gálvez had recruited a large number of Black and mixed-race militia from New Orleans known as the New Orleans Colored Militia. By 1781, this detachment had become experienced veterans, many distinguished by the campaign for West Florida. The involved Spanish regulars hailed from multiple corners of its empire: the regiments of Principe, Spain, Navarre, and Havana.

The British forces consisted of a wider-ranging group of combatants within their ranks. Men from the 3rd Battalion of the 60th Regiment of Foot made up about forty personnel in the assaulting force. Coming in with approximately sixty experienced men was the 3rd Waldeck Regiment, which consisted of German soldiers from the Principality of Waldeck.[14] This regiment had been contracted out by Prince Friedrich Karl August to the British Army since 1776. The Waldeckers had seen action throughout the New York and New Jersey campaign, including taking a part in the successful assault on Fort Washington. The unit was transferred in 1778 to Jamaica, then West Florida in anticipation of Spanish hostilities.[15]

Strengthening the regulars were Loyalist provincial militia regiments from Pennsylvania and Maryland. This united corps of about eighty troops was commanded by Capt. Philip Barton Key, a future U.S. Representative and federal judge, and the uncle of Francis Scott Key.[16] Lt. Joseph Pinhorn led a small contingent of ten to twenty West Florida Royal Foresters, a volunteer group of provincial mounted rangers.[17] Elements of this unit had participated in previous attacks on The Village.[18] It is possible that this detachment of rangers also had Black soldiers, as there were claims that enslaved men were armed and uniformed under their commanders.[19]

Many secondhand sources state that the British in West Florida allied only with the Creek and Choctaw nations. However, numerous intelligence reports across the region provided information of various warriors from different tribes that were cooperating with either (and both) the British or Spanish governments. Along with the Creek and Choctaw nations, the Chickasaws, Uchizes, Tallapoosas, Alabamu and more took part in the raiding of settlements between Pensacola and Mobile, according to these reports.[20] Even within these native nations, there were extensive factions and divisions that uniquely aligned with the great powers in North America. With that said, a great majority of natives that took part in the January 7 attack were from the Choctaw tribe.[21] More well-established alliances were based on previous political connections, personal ties, or trustworthy promises from either the British or Spanish officials in the region, though these usually favored the British who had a longer standing in the region.

Commanding the British party was Waldecker Col. Johann Ludwig Wilhelm von Hanxleden. Throughout the West Florida campaign, Colonel von Hanxleden had earned high esteem from both the British and Spanish armies. Valiant and effective, he was considered by the Spanish to be the best officer for the British on the Gulf Coast during the campaign. Prior to the battle, he had been given the command of the primary fortification in Pensacola, Fort George, as he had an exceptional logistical and engineering skillset.[22] He possessed further qualities that his superior, General Campbell, did not demonstrate, such as consistently seeking for the better care of his troops. In addition to his glaring complaints of the treatment of German prisoners in the West Indies, he provided for his troops as often as he could to make their lives easier in the camp.[23] As proper food was scarce in Pensacola, he personally saw to the troops being fed a freshly slaughtered ox on a weekly basis to improve their morale.[24]

Perhaps even more important was Colonel von Hanxleden’s willingness to work with and learn from the native nations that cooperated with the British. General Campbell saw their allies as unreliable and opportunistic. This led to distrust between the British and the natives. Whereas General Campbell assumed an arrogance over the natives, Colonel von Hanxleden felt they were effective allies and would work and fraternize directly with chiefs and warriors to strengthen their alliance.[25]

Unlike this planned assault in January, the previous three attacks had largely consisted of British-allied natives directed by a small number of British or Loyalists. As these natives (in this case largely Choctaws) from the previous assault on The Village had been significantly defeated, they sought revenge against the Spanish for their losses.[26] General Campbell took advantage of the eagerness of his allies by ordering for a full assault on the fortification, but with rank-and-file troops as the anchor of the force. He, like his Choctaw allies, felt that the Spanish detachment at the settlement was smaller and weaker than it actually was, and was ripe for another attack. He ordered Colonel von Hanxleden to use his discretion to either take The Village by a full-frontal storming assault or by surprise.[27] The British war party departed from friendly territory on the morning of January 3.[28] William McIntosh, father of White Stick Creek chief William McIntosh Jr., and Farquhar Bethune would serve as direct commanders and translators for the Choctaw combatants.[29]

Though General Campbell had faith in his ground forces, he wanted to insure his victory with a two-pronged attack. A small naval fleet sailed out of Pensacola on the afternoon of January 4.[30] The ships were ordered to make their way to the mouth of Mobile Bay, then sail north, off the shore of The Village, a distance of about thirty miles. Commanded by Capt. Robert Deans, the fleet consisted of his flagship, the sloop-of-war Mentor with twenty-four guns, and the smaller sloop Hound. Their orders were to provide support for Colonel von Hanxleden and his troops and defend against any possible Spanish reinforcements coming across the bay from Mobile.[31] The fleet would have to find a way to sail past the coastal redoubt the Spanish had constructed on Dauphin Island at the mouth of the bay.

Reaching the pass of Mobile Bay on January 5, Captain Deans determined that he would elude fire from the redoubt by raising captured Spanish colors, pretending to be incoming friendly ships.[32] The trickery worked to perfection as they not only navigated the pass without a shot being fired but also captured a boat with Lt. Martin Galvano, five soldiers, and seven sailors coming to meet the presumed Spanish fleet. Learning that only about fifteen soldiers were left at their posts, Captain Deans decided to send a landing party the next morning to take the island. Though they were met with musket fire upon landing on the beach, then quickly overwhelmed and dispersed the defending Spanish; the British captured at least three soldiers including the remaining commanding sergeant, and several small arms. The British also burned the barracks on the island and took numerous Spanish slaves and heads of cattle.[33] While the supporting fleet enjoyed success in their raiding on the island, that would be the full extent of their accomplishments. The shallow bar halfway up Mobile Bay made it impassible for any ocean-going vessel to attempt to reach the northern end. On the day of the attack, the most the supporting fleet could do was observe the smoke rising from the battlefield miles away. Knowing they were utterly useless for the assault, Captain Deans set sail that afternoon in an attempt to intercept Spanish ships off the coast of Ship Island.[34]

Despite a torrential downpour that night, the British assault force was right on schedule, reaching the Spanish stronghold before the dawn of January 7 at approximately 6 a.m. Two hundred yards away from the fort, Colonel von Hanxleden decided that he would split his forces in three to surround and take the complex by surprise. He ordered the first prong of the native forces commanded by Bethune and McIntosh combined with the contingent of Royal Forresters to sneak their way around to the backside fort, lying low between the Spanish forces and the bay, waiting for a signal by drumbeat to attack. He then organized his remaining troops into a single column, with his Waldecker Regiment in the front, and the British regulars and provincial militia in the rear. Capitalizing on the scarce light and dense fog, they swiftly and quietly advanced up the path and into the Spanish lines.[35]

Seeing only vague, shadowy figures in the dark, Sublieutenant Manuel de Cordova presumed the them to be friendly militiamen returning to trenches and ordered his men to hold their fire, which would lead to his immediate killing. Without a shot being fired, the attackers passed undetected through the New Orleans Colored Militia manning the outer trenches and came upon the main entrenchments of the regular Spanish forces. Upon passing the outer trenches, Colonel von Hanxleden had the British and provincial troops to go left and flank around the Spanish earthworks in order to penetrate a weaker spot in the defenses. The colonel and his forces did not expect the palisade that had been built and halted in confusion for a moment to assess the situation. In this suspense, all hell broke loose in the twilight as the commander of the fort, Don Ramon de Castro, realized the attack and ordered his men to open fire in a full coordinated defense of musket fire.[36]

At the head of the column, Colonel von Hanxleden and some of his most trusted adjutants fearlessly charged into the muddied main trench that surrounded the stockade, with screams from both forces of their respective “long live the king!” Here, the British suffered their greatest loss right at the start of the action. After aggressive hand-to-hand combat with knives, bayonets, and musket volleys, the entrusted Colonel von Hanxleden was instantly killed with a musket ball to the forehead at the foot of the stockade, along with his lieutenant and adjutant Johann Heinrich Stierlin.[37]

While the Waldeckers were stopped in their tracks with the death of their colonel and his second-in-command, the British and provincial troops under Captain Key enjoyed greater success. Following their flanking maneuver, they dramatically climbed up the sandy-soiled rampart with fury while facing continuous musket volleys and grapeshot. After close quarters fighting, they stormed the left portion of the defenses and took control of one of the Spanish 4-pounder cannons. This forced the Spanish to retreat and defend the plaza of the fort. These positions were held for the next fifteen minutes. According to Spanish sources, though, an attack was made from the backside of the fort where there was no moat.[38] During the course of the battle one of the magazines of the fort was set on fire and produced a large plume of smoke.[39]

Benjamin Baynton, a lieutenant for the Pennsylvania provincials, wrote to his brother about the intense action he experienced, which led to his being wounded both by a musket ball and bayonet. He provided one of the only legitimate firsthand accounts that was not given for government or military purposes. He emotionally wrote:

Out of five gallant sturdy fellows I had before the action singled out to follow me at my Side, and in case of necessity, assist me in mounting the works, only two are left to tell the story; and one of them, a Serjeant, who earnestly requested to attend me, dangerously wounded in two places. They fell fighting by my side. I have to lament on this occasion, beside several brave officers, a most faithful & affectionate servant, into whose arms I fell when I received my wound. I cannot help mentioning the poor fellow, because I feel myself hurt at never having it in my power as I could wish, to show him the sense I had of his services, and particularly the warm attachment he manifested in the most eminent danger, and within three foot of the muzzles of the enemy’s muskets.[40]

At the same time, the New Orleans militiamen that had been cut off by the assaulting troops from the fortification commenced to charge to the wharf on the bay, breaking through the enemy troops. The objective was to retreat to a supply boat that had arrived the previous afternoon. This would prove to be a damaging mistake. During this maneuver, the Choctaws and Royal Foresters, still lying in wait in this area, preyed upon the militiamen with musket fire. Much to the dismay of the militiamen, the boat had been moved further into the bay so that there could be no attempt at such a retreat. The fearful troops were so desperate that a few even attempted to swim and wade their way to the boat. Unfortunately, the pursuing natives closed in on these men in the water and proceeded to scalp them.[41]

With no other options, the surviving militiamen then turned and charged back the way they came. Though they fought aggressively to reach the fort, which was still being struggled over, they suffered additional casualties from the natives seeking to kill and scalp them, and from crossfire from the friendly Spanish positions. In one case a militia officer, Simón Calfá, was even bayoneted to death by confused Spanish troops when charging back into the fort. This counterattack nonetheless proved effective and helped swing the momentum of the battle in favor of the Spanish. In fact, the militia would later be praised by commanders for their counterattack in the battle.[42]

With the Spanish regulars’ and militia’s counterattack, the top commanders now dead, and the Choctaws having never attacked the fort, acting commander Captain Key decided promptly to retreat back to Pensacola, the natives serving as the rear guard. The action lasted a total of about six hours, finally ending around noon as the retreating force burned bridges behind them on the main road.[43]

Lieutenant Baynton intentionally recounted the battle in intensive detail which he felt would be “unpardonable” if he left any omission. He clearly sought to highlight the honor and gallantry of his troops in battle which he felt would be otherwise tarnished by the newspapers. Though he felt there was potential condemnation to do so as an officer and a soldier, he conveyed to his brother the sheer devastation his force faced:

The particulars of this action you will I suppose see in the publick papers; but, this I will venture to assert, no action since the rebellion, (for the numbers) was more severe while it lasted, or where more honor has been reflected on the astonishing intrepidity of the British Troops. They pushed on upwards of two hundred yards through an incessant fire of grape & musket shot, from at least twice their number, entrenched up to their teeth. One continual sheet of fire presented itself for ten minutes. You may judge of the gallantry of the Officers, when you read in the papers that out of ten, six were killed and wounded. It was Bunkers hill in miniature.[44]

Though both sides suffered heavy casualties, the British assault had been a decisive defeat. The Spanish had suffered fourteen killed (including two officers), twenty-three wounded, and seventeen prisoners (sixteen of these from the action on Dauphin Island).[45] The British were initially dealt eighteen dead (including three officers), with twenty-three wounded.[46] Three of these wounded were taken prisoner, with one dying and the other two later being handed over to the British for medical care.[47] According to other escaped prisoners, many of the British wounded from the battle did not survive the three days heavy rain during the retreat and the rough conditions in Pensacola.[48] Juan Gros, the sole Spanish prisoner during the land attack, came upon a dreadful fate. A free Black militiaman from around New Orleans, Gros was soon sold into slavery by the British to a powerful Native American chief. Governor Gálvez himself made it a point to regain his freedom by making it a contingency in the articles of surrender after the Siege of Pensacola.[49] However, Gros would be enslaved for another eight years until his strenuously negotiated manumission by Spanish authorities and comrades. He would return to the service of the militia when his freedom was regained.[50]

The British defeat at The Village was a greater loss than statistics would indicate. General Campbell was no longer able to effectively commence offensive operations from Pensacola for the rest of the war. This included, of course, any advances towards The Village or Mobile. The Spanish secured the vital ferry point and base of operations with their victory and were now able to prepare for a siege of General Campbell’s headquarters in Pensacola. But the greatest British loss, not just of the battle, but quite possibly of the entire Gulf Coast campaign, was the death of Colonel von Hanxleden. Because of his high regard and gallantry, the Spanish buried him with military honors by firing a rocket over his grave.[51] Furthermore, according to historian Max von Eelking, he was buried under a large and magnificent tree and had a fence constructed around his burial mound.[52] Contemporary sources and modern scholars remain consistent that the primary factor leading to the British defeat was the premature death of the colonel. Not only did his death leave the forces without a commanding officer, but it also prevented the signal for the delayed attack of the 400 natives lying in wait.[53]

The loss of this capable officer was the writing on the wall for the British in Pensacola. It was also met with anger as it was reported that General Campbell wanted to immediately counterattack as an act of vengeance but was restrained by his officers.[54] Indeed, the loss of this effective commander, along with two other esteemed officers, likely ended any chance of the British maintaining a foothold in West Florida. With such a casualty rate of exceptionally experienced, effective officers, and the halting of offensive capabilities, the British in Pensacola were left with no momentum, far less leadership capabilities, and broken morale when the Spanish besieged Pensacola that March. When Pensacola fell, Spain regained full control over Florida.

Ironically, Lieutenant Baynton’s concerns over being publicly branded as a disappointment never materialized. Though there were numerous firsthand reports and descriptions of the battle, it, along with the settlement it was fought over, have largely been forgotten. Compared to battles in the region from other eras like the Civil War, The Battle at the Village does not have a real imprint in the public memory. This is despite it being the bloodiest Revolutionary War battle in Alabama history. Why did this small yet regionally vital battle subside in notoriety? The answer: the people.

From 1763 to 1813, control of the Mobile area changed hands from the French to the British to the Spanish and finally, to the American government. While some settler families from each colonial era remained permanently, many left the area for places retained by their respective national governments after each conquest. As they departed with their belongings and families, so too did they take their memories. In essence, the majority of the Mobile area population in 1781 was eventually displaced by an American-centered population by the mid-1800s. Consequently, the collective memory of the Battle at The Village was all but forgotten except for those who sought out the history, like local authors and historical societies.

Unfortunately, this collective memory loss is a microcosm of the long-storied and rich history of the Gulf Coast. Unlike the Eastern Seaboard which never saw a major colonial administrative-population displacement (aside from Native American) and acted as the foundation of the United States’ growth, the Gulf Coast regularly saw population changes in its early history. Every time a population was displaced, their connections and local accomplishments would effectively be erased from that area. Though these histories played a vital role for how the United States formed and operates today, many Americans, both at the national and local levels, now see this as peripheral or irrelevant.

The lack of awareness has now produced a detrimental situation where historical preservation of the battle site is virtually impossible. According to archaeologists, the area where this once important battle took place has now been decimated by virtually unrestricted suburban developments.[55] Unless awareness and scholarship of the rich history surrounding the battle increases, the physical state of the battlefield will deteriorate further, and archaeological work will be even more hindered. Better education both at the local and state levels on the battle would contribute to increased advocacy for the preservation of the site.

In many ways, we can look to Colonel von Hanxleden as a symbol of the current historical status of the battle and its preservation. At one time, the colonel had a well-respected reputation and an impressive record. Now he rests in obscurity, lost to time in disturbed soil so far away from his home. He, along with his and his adversaries’ valor and struggles, now lie underneath a suburban neighborhood which was once marked by a large and dignified tree.

[1] “Observaciones hechas en el reconocimiento de el Village al Río Perdidos emprendida en 22 de julio de 1780,” Mobile, August 1, 1780, Cuba 2359, Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Spain (AGI); Philipp Waldeck, The Diary of Philipp Waldeck, trans. Bruce E. Burgoyne, University of West Florida, John C. Pace Library, Special Collections, M1983-09.

[2] Waldeck, The Diary of Philipp Waldeck.

[3] Bernardo de Gálvez to José de Ezpeleta y Galdeano (confidential), New Orleans, July 18, 1780, Cuba 1377, AGI.

[4] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, New Orleans, July 18, 1780, Cuba 4A, AGI; John Campbell to George Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781, CO:5/597, The National Archives, Kew, UK (TNA).

[5] Ezpeleta to Gálvez. Mobile, January 20, 1781, Cuba 2359, AGI.

[6] Ezpeleta to Pedro Piernas, Mobile, January 15, 1781. LEG, 6912, 4, Archivo General de Simancas, Spain (SGU); Ezpeleta to Gálvez. Mobile, January 20, 1781; Alexander Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, February 10, 1781, CO:5/82, TNA; Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781.

[7] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781.

[10] “La Mobila en su Hora Decisiva,” José de Ezpeleta, Gobernador de La Mobila: 1780-1781 (Seville: Publications de la Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos de Sevilla, 1980), chapter IX.

[11] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781.

[12] Ezpeleta to Manuel Cabello, Mobile January 10, 28, February 2, 1781, Cuba 116, AGI.

[13] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781.

[14] Declaración de desertores, Mobile, March 2, 1781, Cuba 3A, AGI.

[15] Waldeck, The Diary of Philipp Waldeck.

[16] Declaración de desertores, Mobile, March 2, 1781; “KEY, Philip Barton.” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, bioguide.congress.gov/search/bio/K000159.

[17] Declaración de desertores, Mobile, March 2, 1781.

[18] Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, October 31 and November 30, 1780, CO: 5/82.

[19] Memorial of Adam Chrystie, March 4, 1784, Audit Office 13/99/116-117, Library and Archives Canada.

[20] “El Problema Indio,” in Francisco de Borja Medina Rojas, José de Ezpeleta, Gobernador de La Mobila: 1780-1781 (Seville: Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1980).

[21] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781.

[22] Waldeck, The Diary of Philipp Waldeck.

[23] Daniel Krebs, A Generous and Merciful Enemy: Life for German Prisoners of War During the American Revolution (University of Oklahoma Press, 2013).

[24] Waldeck, The Diary of Philipp Waldeck.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, November 30, 1780.

[27] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781.

[28] Campbell to Johann von Hanxleden, January 2, 1781, AGI Cuba, 1233.

[29] Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, February 10, 1781.

[30] Robert R. Rea and James A. Servies, The Log of H.M.S. Mentor, 1780-1781: A New Account of the British Navy at Pensacola (University Presses of Florida, 1982).

[31] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 5, 1781.

[32] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 11, 1781, PRO CO:5/597, TNA.

[33] Ibid; Rea and Servies, The Log of H.M.S. Mentor.

[34] Ibid; Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 11, 1781.

[35] Benjamin Baynton to Peter Baynton, Pensacola, February 2, 1781, Pennsylvania State Archives (PSA), MG019, Sequestered Baynton, Wharton and Morgan Papers, 1725-1827, Part III, Baynton Family Papers, 1770-1827, Correspondence of Benjamin Bayton, 1777-1785; Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 11, 1781; Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, February 10, 1781; Ezpeleta to Gálvez. Mobile, January 20, 1781.

[36] Ezpeleta to Gálvez. Mobile, January 20, 1781.

[37] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781; Ezpeleta to Navarro, January 22, 1781, AGI Cuba, 1233; Benjamin Baynton to Peter Baynton, Pensacola, February 2, 1781; Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 7 and 11, 1781, PRO CO:5/597; Peter Chester to John Dalling, Pensacola, January 10, 1781, PRO CO:137/80; Campbell to Dalling, Pensacola, January 9, 1781, PRO CO:137/80; Campbell to Henry Clinton, Pensacola, January 7 & February 15, 1781, PRO 30:55/89.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Carl Philipp Steuernagel, Carl Philipp Steuernagel Diary, 1773-1783, trans. Bruce E. Burgoyne, University of West Florida, John C. Pace Library, Special Collections, M1983-09; Rea and Servies, The Log of H.M.S. Mentor.

[40] Benjamin Baynton to Peter Baynton, Pensacola, February 2, 1781.

[41] Ezpeleta to Gálvez. Mobile, January 20, 1781; Ezpeleta to Navarro, January 22, 1781; Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 7 and 11, 1781; Chester to Dalling, Pensacola, January 10, 1781; Campbell to Dalling, Pensacola, January 9, 1781; Campbell to Clinton, Pensacola, January 7 and February 15, 1781.

[42] Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781; Ezpeleta to Navarro, January 20 and 22, 1781.

[43] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 7 and 11, 1781; Baynton to Baynton, Pensacola, February 2, 1781.

[44] Baynton to Baynton, Pensacola, February 2, 1781.

[45] Ezpeleta, “Relacion de los Muertos, Heridos, y Prisioneros en el ataque del Destacamento de la Aldea el dia 7 de Enero de 1781”, Mobile, January 15, 1781, S.G.U., LEG, 6912, 4.

[46] Campbell. “Return of the Killed and wounded at Village opposite Mobile, the 7th January 1781”, Pensacola, January 11, 1781, PRO CO:5/597; Ezpeleta to Gálvez, Mobile, January 20, 1781; Ezpeleta to Piernas, Mobile, January 10, 1781, AGI Cuba, 2359.

[47] Ezpeleta to Piernas, Mobile, January 10, 1781.

[48] Ezpeleta to Diego Josef Navarro, Mobile, January 26, 1781, AGI Cuba, 1233.

[49] Ezpeleta, “Relacion”, January 15, 1781; Bernardo de Gálvez, Diario de las Operaciones de la Expedicion contra la Plaza de panzacola concluida por las armas de S.M. católica, Baxo Las Órdenes del mariscal de campo D. bernardo de Galvez (Havana, 1781); Kimberly S. Hanger, Personas de Varias Clases y colores: Free people of color in Spanish New Orleans, 1769-1803, PhD Diss, University of Florida, 1991.

[50] Hanger, Personas de Varias, 1991.

[51] Steuernagel, Carl Philipp Steuernagel Diary, 1773-1783.

[52] Max von Eelking, Die deutschen hülfstruppen im nordamerikanischen befreiungskriege 1776 bis 1783 (Hannover: Helwing, 1863).

[53] Campbell to Germain, Pensacola, January 7 and 11, 1781; Cameron to Germain, Pensacola, February 10, 1781.

[54] Ezpeleta to Navarro, Mobile, January 26, 1781.

[55] Daniel T. Elliott, et al, Revolutionary War/War of 1812 Historic Preservation Study Vol. 1 (Ellerslie, GA: Southern Research, Historic Preservation Consultants, Inc., 2002).

10 Comments

Anthony, Thanks so much for researching, composing, and sharing this. Cheers!

Thank you!

Great article! I love that the Journal publishes detailed and well-researched articles on these (mostly) unknown episodes of the war.

It appears that there is a concerted effort among many researchers and historians to focus on the event outside of the thirteen colonies. One challenge I have found to this the language barrier. In this case it would Spanish but in my own research it’s been translating French documents.

Thanks for your comment! And yes it is challenging in the translation process. I feel lucky to live in a time where translation can be done so easily with a phone or other apps. I have also projects translating French and I wouldn’t be able to do it without so.

Anthony; that was a fascinating & informative article. I live in ATL and am somewhat familiar with de Galvez and the ‘Pensacola’ actions in the Rev War, but this was entirely new information to me. Thanks much for your fine effort. Next drive down to New Orleans I’d like to check out the remnants of this site.

Thanks, Michael! Yea, your best bet would be at Village Point Preserve. Its not on the exact site, but it has a little sign for the battle and also is a nice historic/nature park for the area. You also can however, get a visual on the site looking south at the end of the pier in the park.

Wonderful article. On your map I live in Pace FL, at the north end of Pensacola Bay. It is now known as Escambia Bay. I’m a member of the Pensacola SAR Chapter. Along with the city we just celebrated the Battle of Pensacola. I’m sure knowledge of this Battle is new to our members, me included. Is the site of the battle near present day Daphne AL? There is a Village Point Park Preserve here on the Eastern Shore. Love the map. It encompasses what the Navy calls Area I on the Pensacola Training Chart. With what I know now, I could have given my students a bit of a history lesson having flown this area as a Navy Flight instructor for many years.

Hi Gunter,

Yes, the site of the battle would’ve occurred south of Village Point Preserve. Based upon other more detailed historical maps (couldn’t include in the article because the UK has a strict copyright payment law) and the 1856 Mobile Bay naval chart, I believe the harbor/anchorage area of the battle was around what would later be either Starke’s Wharf or Belle Rose Wharf. And yea, this battle is largely a footnote between the Siege of Fort Charlotte and the Siege of Pensacola. I was hoping to bring a bit of awareness to what I believe is a locally important historical resource. Thanks for giving it a read!

Nice article- well written and quite evident you studied the sources closely. Congrats. The Ezpeleta book has particularly good details on this engagement and quotes heavily from the source documents. I looked into this battle quite a bit when I was working on my Colbert book as the Spanish records place Colbert at the engagement. I assisted with a painting on the engagement too which is displayed at the American Revolutionary War in the West Museum Exhibit as a new item that was added last year. Hope to see more from you on this theater. I will be sure to mention your article to some folks at the American Revolutionary War in the West history conference this fall as I suspect some of them will be interested.

I think that this is a remarkable story. And, your telling which is both detailed and poignant is exemplary. Thank you.