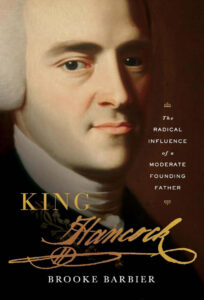

BOOK REVIEW: King Hancock: The Radical Influence of a Moderate Founding Father by Brooke Barbier (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2023)

To my mind, there are three main currents of historiography of the American Revolution in the present day. The first is the de-deification of the Founding Fathers, seen in both published works and in the demolition of statues throughout the United States. The second (and corollary) is the documentation of the perspectives and contributions of marginalized and under-represented groups previously ignored for decades.

The third and, I think, the most fascinating is the elevation of that group of contributors to the Revolution who existed one strata below the Washingtons, Adams’s, Franklins and Jeffersons—the “B Level” list of actors, so to speak. The books forefront in this genre for me are Walter Stahr’s John Jay, Ira Stoll’s Samuel Adams: A Life, and Nancy Isenberg’s Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr—among a host of others.[1]

The third and, I think, the most fascinating is the elevation of that group of contributors to the Revolution who existed one strata below the Washingtons, Adams’s, Franklins and Jeffersons—the “B Level” list of actors, so to speak. The books forefront in this genre for me are Walter Stahr’s John Jay, Ira Stoll’s Samuel Adams: A Life, and Nancy Isenberg’s Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr—among a host of others.[1]

The latest, superlative contribution is Brook Barbier’s King Hancock.[2]

Known by most Americans only idiomatically for his large, ornate signature on the Declaration of Independence, Hancock has been consigned to irrelevance by history. Barbier corrects this. It is true that Hancock won no great battles, signed no great treaties, nor promulgated any lasting laws. As an “extravagant moderate,” though, he played a crucial role in saving the Revolution—both in his home state of Massachusetts and for the country as a whole—at several crisis points in the latter years of the War of Independence and in the dangerous years before the Constitution.[3]

It is here that Barbier is masterful. In the opening chapters of the book, she paints the picture of a sympathetic figure who could appeal to people up and down the social ladder. Eager to charm the masses through “sumptuous entertaining and plentiful drink,” he could—and often did—talk with tradesmen and others on the lower rung of the social hierarchy on something of an equal footing.[4]

This flexibility was Hancock’s greatest strength, and enabled him to craft approaches that could please the most amount of people—and diffuse tension when necessary. As Barbier writes,

He wanted people on his side and learned how to win their favor. It was not through violence, fear mongering, or coercion; instead, Hancock assessed the interests of his people, as well as his own, and usually supported those.[5]

It was this adroitness that would serve him in the later years of both his public career and his life, a time in which Hancock played a leading role in saving the Revolution on three occasions. Barbier’s discussion of this is exemplary.

Shortly after the French alliance had officially been consummated in 1778, the French navy under the Comte D’Estaing docked in Boston harbor after an abortive attack on Newport, Rhode Island. What ensued was a potentially crippling paradox for the American cause, for, as Barbier writes, “The French alliance was critical to the United States winning the war, and many colonists—especially those in Boston—hated the French.”[6]

The French were Catholic in a city of Puritans—a city that annually celebrated “Pope’s Day,” whereby rival gangs would seek to capture the other’s effigial pope and then ostentatiously destroy it. During a time of war and scarce resources, the arrival of thousands of French combatants put further strains on food supplies and prices. When the French set up their own bakery, but then refused to sell their goods to anyone outside the French navy, tension boiled over in much the same way it had when Redcoats occupied the city years before.

In stepped Hancock and his extravagant moderation. “Hancock was the closest thing to an aristocrat in Massachusetts and he fit in well with the officers who expected their hosts to be refined in dress and manner and provide fine entertainment.”[7]At great financial cost to himself—and immense expenditures of time, work, and spirit on the part of his household staff, Hancock ingratiated the goodwill of D’Estaing and the French officers. So too did he use his influence—cultivated, as Barbier writes in the first half of her book, in the years leading up to the War of Independence—with Bostonians to prevent further conflict with the French.

Benjamin Franklin justifiably receives the lion’s share of the credit for achieving an alliance with France, but Hancock’s efforts preserving the alliance in its infancy must merit commensurate praise. As Barbier writes, “Hancock helped secure the alliance that became crucial to winning the Revolutionary War. He did so using the tools of soft power: shaping others’ attitudes and earning loyalty with hospitality and generosity, rather than coercion and fear.”[8]

This moderation and generosity would once again be called upon after the war. During the second of his non-consecutive terms as governor of Massachusetts, the state—and the country—stood on the precipice of disaster thanks to a financial crisis of indebtedness, especially in the western part of the state where farmers, many of them veterans of the war, were unable to pay back their debts with anything other than worthless paper money. It was this crisis that lead to the infamous “Shays’ Rebellion,” with farms being foreclosed and court houses being shut down by extralegal and armed citizen groups in response.

Hancock, and really Hancock alone, softened the situation in two ways. Privately, as a creditor himself, he accepted repayment for debts in paper money when others of his class would not. Publicly as governor, he agreed to a reduction in his salary and pardoned those involved in the “rebellion.” As Barbier puts it, Hancock “knew that healing the rift, not widening it, was good for the state.”[9]

Hancock’s final great contribution to his state and country came at the very end of his life, when Massachusetts’ ratifying convention sat deadlocked in Boston. The locus of Revolution from the very beginning, anxious observers throughout the thirteen states knew that without Massachusetts’ assent to the new constitution, it was almost certainly doomed.

Neutral through most of the debate, an aging and ailing Hancock limped into the convention hall to provide his recommendation to the assembled delegates and spectators. The account that follows is historical drama at its most captivating, and Barbier captures it beautifully. Determined, as ever, to bridge the divide between Federalists and anti-Federalists, Hancock announced to a hushed audience that he would support the proposed Constitution, but with amendments. “Characteristically,” Barbier writes, “he had chosen a moderate path. He split the difference between support for and opposition to the Constitution.”[10]

With the vote hanging on a razor’s edge, Hancock’s qualified support for the Constitution made a determinative difference: not only did he help persuade enough delegates to vote for ratification (though just barely), but, equally importantly, his influence convinced a number of those who had voted against to accept the results and support the new plan of government going forward.

Once again, Hancock had been decisive in preserving the Revolution and the Union—a dazzling final jewel in the crown of “King Hancock.” As Barbier aptly sums up, “For decades he worked in service of Massachusetts, the North American colonies, and the United States, and sacrificed his health and wealth to do so. Many men of the founding era who similarly toiled are known only to specialists, but forgotten to popular memory.”[11]

Thanks to Brooke Barbier, that is now a little less true of John Hancock.

PLEASE CONSIDER PURCHASING THIS BOOK FROM AMAZON IN HARDCOVER or KINDLE. (As an Amazon Associate, JAR earns from qualifying purchases. This helps toward providing our content free of charge.)

[1]See Walter Stahr, John Jay(New York: Hambledon & Continuum, 2006); Ira Stoll, Samuel Adams: A Life (New York: Free Press, 2008); and Nancy Isenberg, Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr (New York: Penguin Books, 2007).

[2]Brooke Barbier, King Hancock(Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2023).

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...