Major Peter L’Enfant is most well-known for his 1791 “wholly new” plan for the Federal City that would become Washington, DC. Fewer are aware of his previous experience during the Revolutionary War where he served as an aide-de-camp, engineer, and sometimes as an artist and light infantry officer. This military service, coupled with his fine arts education and post-war career as an architect were the near-perfect prerequisites for his most famous role as the author of the most important civic design project in American history.

Pierre Charles L’Enfant was born in Paris on August 2, 1754, and descended from a long line of artists. His father, also named Pierre, was a “Painter in Ordinary” to King Louis XV.[1] Before his son’s birth, he was appointed an academician to the Academie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture.[2] By 1771, the younger Pierre was at the academy receiving a fine arts education which also included the study of architecture, landscape architecture, science, and mathematics.[3] In contrast to many French officers who would serve in America as engineers or in the artillery service, there is no record that L’Enfant ever received any pre-war education or training as a soldier or engineer.

L’Enfant’s entrée into the American war was a social connection with the playwright (and covert agent) Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. By mid-June 1776, Beaumarchais had received funding for the Roderigue Hortalez & Cie, a front organization whose sole purpose was secretly procuring and delivering French and Spanish arms and war materiel to American rebels.[4] By August, L’Enfant’s name was on a list of several dozen men to serve in America with the promise of commission in the Continental Army.[5] In December 1776, he was on board the Amphitrite, the first Beaumarchais ship to sail for America.[6] Before departure, he was commissioned a brevet lieutenant in the French colonial troops, ostensibly to provide him a degree of protection from imprisonment should he be captured at sea.[7] On the ship, L’Enfant was under the temporary command of artillery expert Gen. Phillipe Charles Tronson du Coudray. It was likely at the latter’s insistence that the Amphitrite returned to port after a few weeks due to a lack of provisions.[8] L’Enfant was in Nantes in February 1777, where Beaumarchais was worried about the young officer, ordering an assistant to provide him with funds for his sustenance.[9] The Amphitrite soon departed without L’Enfant, arriving in Portsmouth, New Hampshire in April, 1777.

By March 1777, Beaumarchais reported he had ten total vessels at sea.[10] L’Enfant’s path and course to America is not clear, but he almost certainly departed on one of the remaining ships and was in Charlestown, South Carolina, with six other French officers in August 1777.[11] He could have possibly arrived there as early as May on a direct route, however, most of the Beaumarchais ships sailed for Santo Domingo or Martinique where they offloaded men and material and either returned to France or sailed to America.[12] L’Enfant’s voyage roughly parallels Lafayette’s journey to America, except that the latter man’s ship appears to have departed later and arrived earlier in South Carolina. Lafayette’s purchased vessel, La Victoire, sailed in March from Spain (bypassing the Caribbean) directly to South Carolina and arrived on June 13. Lafayette was already in Philadelphia (by late July 1777) by the time L’Enfant was first mentioned in Charlestown.

L’Enfant and the six other officers had arrived in York, Pennsylvania, by October 2. A few days later, they were being paid to “tender their services to the United States.”[13] Preceding L’Enfant’s arrival in Pennsylvania was General Coudray, who wrote of L’Enfant as a “creature of B__ [Beaumarchais]” but also had “some talent for drawing figures . . . but nothing of use for an engineer.”[14] Coudray drowned crossing the Schuylkill River in mid-September 1777.

Throughout the previous year Gen. George Washington, among others, noted the surfeit of French officers in America and the numerous difficulties in finding suitable positions for them. The predominant causes were their lack of knowledge of the English language, few open officer assignments, the unlikelihood of them raising American troops, their requests for high military ranks, and in some cases, the misrepresentation of their abilities and experience. By November 1777, Congress had granted funds to return forty of these men to Paris.[15] L’Enfant and most of his French companions who traveled from Charlestown with him were on the list.

By early 1778, L’Enfant was in Boston, seemingly awaiting passage back to France. Fatefully, he encountered the recently arrived Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben who prevailed upon him to forgo his departure. Steuben soon requested a brevet commission of captain from Congress for L’Enfant to serve directly under him as his aide.[16] L’Enfant is not listed among Steuben’s companions to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, but is mentioned in General Washington’s general orders of May 5, 1778. “Captain Lanfant” was one of several officers directing the “Grand Parade” of troops and the feu de joie to celebrate the newly formed French alliance.[17] Soon after, Lafayette requested Washington sit for a portrait by L’Enfant. The work, drawn from life at Valley Forge, was held privately for a time, but its current whereabouts are unknown.[18]

Captain L’Enfant was likely at the Battle of Monmouth with General Steuben on Bald Hill reconnoitering the British retreat on the morning of June 28, 1778. Lt. Col. John Laurens noted that he, Steuben, and his “aides” were nearly captured by General Cornwallis’s dragoons early in the engagement.[19] Another account notes only Steuben, Laurens, aide Benjamin Walker, and a “small dragoon escort” were present and pursued by Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe and the Queen’s (American) Rangers.[20] Steuben’s other aide and secretary, Peter Stephen Du Ponceau, noted very little in his autobiography about the day, only that he was with the army during the battle.[21] While L’Enfant was not conspicuous in accounts of the battle, it would have been his first exposure to combat on a large scale. The experience, minimal as it was, may have influenced his decision in the coming months to relocate to the southern theater of the war.

In September 1778, an event came to light that could have proved disastrous to L’Enfant’s future in the army. The previous November, while he was awaiting return to France, he reportedly wrote a letter to a French acquaintance critical of Congress and disparaging American officers and soldiers. This letter was captured and published in the New York newspaper Royal Gazettein June 1778. L’Enfant was quoted as writing that Congress “refused complying with any of their promises” and was guilty of a “breach of justice and good faith.” In regard to his brothers-in-arms, they were “cowards of the first order . . . scared of the least noise, and ever ready for flight.” In a subsequent letter to George Washington, L’Enfant attributed the account to a British attempt at disinformation, writing, “they have most villainously abused the liberty of the translator and have altered the words and phrases of my letter.” L’Enfant closed by noting that his service and conduct in the previous year should stand to disprove the newspaper’s claims and offered to write a disavowal letter to the Gazette.[22]Beyond this letter to Washington, there is no further word on the matter, including the rebuttal letter.

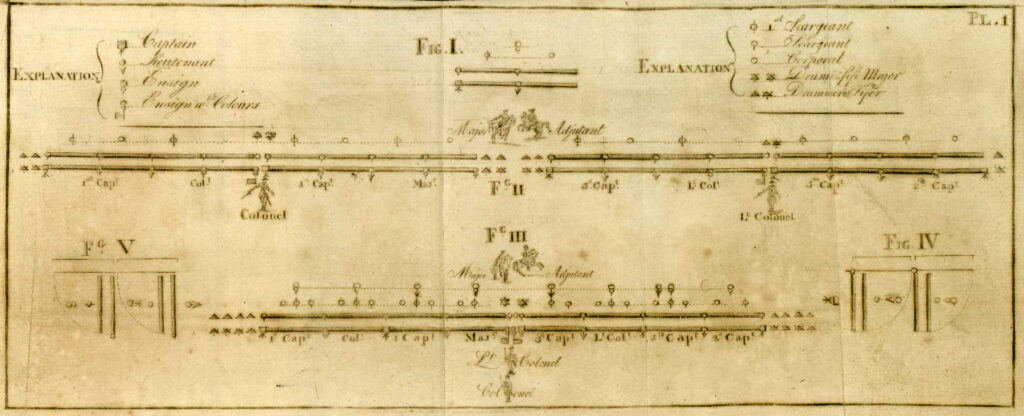

In the fall and winter of 1778-9, General Steuben with a select team of one American and three French officers settled in Philadelphia to write a manual of arms for the Continental Army.This volume, colloquially known as the “Blue Book,” was formally entitled Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States. L’Enfant’s role in the volume, as the only man with artistic training, was to draft the eight “plates” or illustrations detailing camp and troop formations. The “Blue Book” was completed by April 1779 with General Washington’s and Congressional approval. Congress awarded L’Enfant $500 for his efforts and officially promoted him to captain of engineers retrograded back to February 1778.[23] During this period, he began to sometimes use the anglicized first name of Peter in his correspondence. He was not, however, consistent in this usage as he most often initialized his name as P.C. L’Enfant.

Almost immediately after completion of the “Blue Book,” L’Enfant “took leave” of Steuben to find distinction in what he termed the new “seat of war.”[24] After a twenty-nine-day journey, L’Enfant arrived outside Charlestown, South Carolina, in mid-May 1779. His first letter to Steuben implies he entered the city without opposition during the brief siege by British troops commanded by Gen. Augustine Prevost. Prominent in this letter is the description of the recently arrived General Casimir Pulaski’s first action in the theater, losing seventy-five men and four officers.[25] The account is consistent with the action known as the Old Race Track skirmish.[26] It was to be the first of many military defeats L’Enfant would experience in the coming year while with the American army

In Charlestown, L’Enfant joined his friend Lt. Col. John Laurens who also recently arrived but had already been wounded in battle at Coosawhatchie on May 3, 1779.[27] Before Laurens left Philadelphia, he had received approval from Congress to raise a regiment of enslaved soldiers in South Carolina.[28] L’Enfant was promised a light infantry command and promotion to major under Laurens.[29] When the South Carolina General Assembly overwhelmingly rejected the proposal, L’Enfant resumed his duties in the engineering corps.[30] Interestingly, he claimed that one reason Laurens’ proposal was rejected was that the enslaved men were needed for a labor corps to construct the town’s defenses. He sarcastically wrote to Steuben that no labor could be done without the enslaved men, including the felling of a single tree.[31]

There are many indications that L’Enfant was deeply unhappy with the state of affairs in the South. In letters to Steuben, he mused that if he did “a foolish thing in America it was to come to this province.”[32] He described the difficulty traversing the many creeks and rivers, the eroded spirit of the local population, the vastly inflated currency, the lack of initiative of American officers, and uncoordinated military operations.[33] As one example, he described a June 17, 1779 engagement (possibly referring to the battle at Stono Ferry), where Gen. Benjamin Lincoln did not wait for Gen. William Moultrie to attack a British position.

L’Enfant’s first direct combat experience came on October 8, 1779, the day before the failed French-American main assault on British-occupied Savannah, Georgia. According to the prevailing sources, L’Enfant was seriously wounded while leading five men to set fire to the abatis in front of the town’s fortifications.[34] One account notes the men succeeded in setting fire to the abatis but the wood, being recently cut, was too moist to remain alight.[35] In the ditch before the entrenchments, he either suffered burns or, more likely, was wounded by musket fire in one or both legs. One observer reported him dead, judging by the severity of the wound. In contrast to other battles he described, L’Enfant was proud of the bravery exhibited on the occasion. In 1782, he recalled to General Washington that “it is without partiality, I say that never were greater proofs of true valor exhibited than at the assault at Savannah. Never was there a more favorable moment for the troops of this Continent.” [36]

By December 1779, L’Enfant had largely healed from his wounds but remarked on the “impotency” of his leg. Given that and the state of finances, he requested funds so he could be removed from Charlestown.[37] L’Enfant was still there when 150 British ships arrived off the South Carolina-Georgia coast in mid-February 1780.[38] He recalled posting himself “wherever he could render the best service.”[39] This certainly entailed assisting in the ongoing fortification efforts but it also briefly involved a skirmish north of the town. Mounted on horseback, he noted joining Lieutenant Colonel Laurens on March 30, attacking the vanguard of a column of German jaegers and British light infantry three miles north of the town.[40] It was very likely his last direct involvement in combat during the war.

During the night of April 25, Gen. Louis Duportail, L’Enfant’s commanding officer and commandant of the corps of engineers, arrived in the town by traveling through the woods in the dead of night, bypassing British patrols.[41]Duportail immediately assessed that the defenses would not withstand a prolonged assault. In contrast to the siege of the previous year, the British now had sufficient troops in addition to heavy artillery. With the British army and navy virtually encircling the town, he unsuccessfully recommended the evacuation of the garrison.

After the surrender of Charlestown on May 12, L’Enfant received a partial parole and was confined to Christ Church Parish, north of Charlestown. He simply described the experience as “my hard captivity.”[42] The circumstances of his confinement may not have been too different from General Duportail, who was held fifteen miles from Charlestown and despaired over the oppressive heat, sandy soil, insufficient diet, and being covered with insect bites.[43] By November 1780, Duportail, General Lincoln, Lieutenant Colonel Laurens, and several other higher-ranking officers were exchanged. Durportail’s only regret in leaving the theater was that his fellow French engineers were staying behind (Colonels Cambray, Laumoy, and Captain L’Enfant).[44] L’Enfant did not leave the vicinity of Charlestown until his general parole in July 1781 which restricted him to a distance of twelve miles from any military garrison.[45] As he was not yet fully exchanged, he did not join Duportail in engineering of the siegeworks at Yorktown in October 1781.[46] It was not until January 1782 that L’Enfant was finally exchanged for Lieutenant de Heyden of the Anspach Yagers.[47]

The year after the surrender of Yorktown proved to be an exceptionally creative period for L’Enfant. By April 12, 1782, he was noted as “on furlough” from the corps of engineers at West Point.[48] The reason for the release from duty was the announcement of the birth of the dauphin, heir of King Louis XVI. L’Enfant was directed to Philadelphia where he was granted the honor to design and erect a temporary pavilion for the French-American celebration. Held on July 15, 1782, the event was attended by Washington, Lafayette, Rochambeau, French Ambassador La Luzerne, leaders from Congress, and hundreds of others. L’Enfant’s design for the pavilion received particular attention, being hailed for its classical elegance and grace.[49] This small project was a breakthrough for his later career. Immediately after the war, it led to numerous architectural and design commissions, culminating in the designs of Federal Hall in New York City and, most famously, the plan for the nation’s capital.

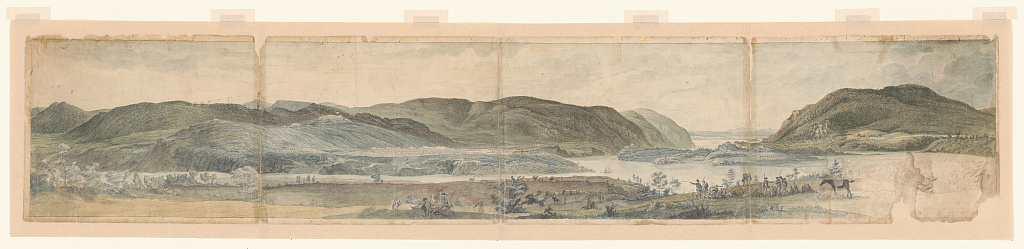

Sometime during 1782, L’Enfant painted two sweeping panoramas of the fortifications of West Point on the Hudson River and General Washington’s headquarters at Verplanck’s Point. The latter watercolor painting details what is believed to be “the only known wartime depiction of Washington’s tent by an eyewitness.”[50] The seven-and-a-half-foot-long painting was recently purchased by the Museum of American Revolution in Philadelphia and is the feature of a current online exhibit.[51] Along with the elaborate pavilion design, the paintings are the first examples of L’Enfant’s emerging “en grand” artistic vision which would come to be one of his defining characteristics.

Before the July fête, disconcerted by a younger officer’s promotion to major, L’Enfant wrote to General Washington seeking a promotion.[52] By May 1783, a Congressional committee which included Alexander Hamilton finally promoted L’Enfant to brevet major.[53] Now a field officer, L’Enfant was almost immediately requested by Washington to design a badge to be issued to the founding members of the Society of the Cincinnati. Boldly disregarding Washington’s desire for an oval design, L’Enfant proposed the bald eagle emblem which became the iconic hallmark of the society.[54] He also created designs for the society’s medal and membership certificate.[55] L’Enfant sailed for Paris in November 1783 to have the badges manufactured and to personally induct French officers into the society.[56] He returned from France in 1784 and became one of the very few French Continental officers to remain in America after the war.

It is hard to envision that Pierre—or Peter—L’Enfant would have been selected to formulate the plan for the nation’s capital had he not been a Continental Army officer. While he certainly would have been qualified for the position without his military service, it was the connections with men like Washington and Hamilton that proved to be critical to his appointment. However, these military bonds were not infinite and immutable. L’Enfant’s intransigence and “artistic temperament” during the latter part of 1791 proved to be too much for Washington and the District commissioners. L’Enfant’s dismissal or resignation (accounts vary) from the post certainly negatively affected his career trajectory. While he was later offered some payment for his work, opportunities for significant design commissions, and even a teaching position at West Point, he was too proud to accept them. Beyond the problems of his occupation was his wounded sense of honor. Perhaps the greatest slight one might have bestowed on the artist and designer was not even being credited with the capital design on engravings of the published plan.

Major Peter L’Enfant died on June 15, 1825, in Prince George’s County, Maryland. A modest obituary in the National Intelligencerdid credit him as being the “author” of the plan of Washington DC.[57] He may have remained an obscure figure if not for the City Beautiful movement of the late nineteenth century. With the movement’s heightening of the public’s appreciation of civic architecture came the belated recognition and admiration of the brilliance of L’Enfant’s plan. By 1908, the esteem for L’Enfant rose to such a degree that plans were made to reinter his remains within a new public memorial. He was the first foreign-born man to receive the honor of lying in state at the U.S. Capitol. Soon after, his remains were finally reinterred on a prominent hill in Arlington National Cemetery overlooking the city he designed. On the one-hundredth anniversary of his death, a second memorial marker was placed at his original gravesite in Maryland.

In the years after the war, L’Enfant was often described by those close to him as the “old major.” Others less acquainted with him may have been under the impression his first name was “Major” and not Peter, judging the way some addressed him. Certainly contributing to this was L’Enfant’s attire; being observed wearing a blue military coat on his many visits to government claim offices. All aspects of his life considered, it is clear that Peter L’Enfant’s sense of honor and identity were very closely tied to his major’s commission. This military identity extended further into the twentieth century where his two epitaphs prominently note his military rank of major. The readers of these inscriptions may go so far as to contemplate what alternative form and shape the nation’s capital city might have taken had it not been for Maj. Peter Charles L’Enfant of the Continental Army.

[1]H. Paul Caemmerer, The Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant (New York: DaCapo, 1970), 1-3.

[3]Kenneth R. Bowling, Peter Charles L’Enfant: Vision, Honor, and Male Friendship in the Early American Republic (Washington, DC: Printed for The Friends of the George Washington University Libraries, 2002), 4.

[4]Brian N. Morton & Donald C. Spinelli, Beaumarchais and the American Revolution (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2003), 47.

[5]Caemmerer, Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 25.

[6]Tom Shachtman, How the French Saved America: Soldiers, Sailors, Diplomats, Louis XVI, and the Success of a Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s, 2017), 55-56.

[7]Caemmerer, Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 9.

[8]Silas Deane to Beaumarchais, “American Commissioners in France to the Committee of Secret Correspondence,” Naval Documents of the American Revolution, William Bell Clark et al. ed. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1962 – ), 8:531-533; 512.

[9]Caemmerer, Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 39-40.

[11]John Dorsius to Congress, August 19, 1777, Charles Town, SC, Papers of the Continental Congress, M247, Roll 94, Volume 7, Item 78, Page 113; Robert Howe to Congress, August 15, 1777, Charles Town, SC, PCC, M247, Roll 178, Item 160, Page 368.

[12]Naval Documents, 8:956-7., 9:451; Elizabeth S. Kite, “Lafayette and His Companions on the “Victoire”,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia Vol. 45 No. 1 (March 1934), 5.

[13]Jerome Le Brun Bellocour to Congress, October 2, 1777, York Town, PA, PCC, M247, Roll 91, II, 275; Journals of the Continental Congress, October 4, 1777, 9:765.

[14]Caemmerer, Life of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, 41.

[15]Journals of the Continental Congress, November 7, 1777, 9:877.

[16]Baron von Steuben to Henry Laurens, May 21, 1778, Valley Forge, PA, Henry Laurens Papers, South Caroliniana Library, University of South Carolina, Accessions 13612.

[17]General Washington’s General Orders, May 5, 1778, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-15-02-0039.

[18]Scott W. Berg, Grand Avenues: The Story of Pierre Charles L’Enfant, The Visionary Who Designed Washington, D.C. (New York: Random House, 2000), 55.

[19]John Laurens, “The Army correspondence of Colonel John Laurens in the years 1777-8,” William G. Simms ed. (New York, n.p., 1867), 202.

[20]Mark E. Lender & Garry W. Stone, Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma, 2017), 241.

[21]James L. Whitehead, “Notes and Documents: The Autobiography of Peter Stephen Du Ponceau,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 63, No. 2 (April 1939), 212.

[22]Pierre-Charles L’Enfant to George Washington, September 4, 1778,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-16-02-0550.

[23]George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Continental Congress, April 3, 1779, Resolution Appointing of Pierre Charles L’Enfant to Corps of Engineers, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Library of Congress.

[24]L’Enfant to Washington, February 18, 1782,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07839.

[25]Edith von Zemensky & Robert J. Schulman (eds.), L’Enfant to Steuben, May 24, 1779, The Papers of General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, 1777-1794, (Library of Virginia, microfilm), Roll I, 383-392.

[26]David K. Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775–1780 (Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 108.

[27]Gregory D. Massey, John Laurens and the American Revolution (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2000), 134.

[30]L’Enfant to Washington, February 18, 1782,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07839.

[31]L’Enfant to Steuben, Steuben Papers, August 8, 1779, Roll II, 4-6.

[33]L’Enfant to Steuben, May-December 1779, Steuben Papers, Roll I: 383-392, 438-441; II:4-6, 148-154.

[34]Wilson, The Southern Strategy, 157.

[35]Charles C. Jones, Jr. (ed.), The Siege of Savannah, 1779 as Described by Two Contemporaneous Journals of French Officers (Albany, NY: Joel Mussel, 1874), 27.

[36]L’Enfant to Washington, February 18, 1782,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07839.

[37]L’Enfant to Benjamin Lincoln, December 4, 1779, Boston Public Library,archive.org/details/lettertogeneralb00lenf/mode/2up.

[38]Carl Borick, A Gallant Defense: The Siege of Charleston, 1780 (Charleston, SC: University of South Carolina, 2012), 31

[39]L’Enfant to Washington, February 18, 1782,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07839.

[40]Borick, A Gallant Defense,105.

[41]Elizabeth S. Kite, Brigadier-General Louis Lebègue Duportail, Commandant of Engineers in the Continental army, 1777-1783 (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University, 1933), 172

[45]James Dudley Morgan, Thomas Attwood Digges, William Dudley Digges, and Pierre Charles L’Enfant, James Dudley Morgan collection of Digges-L’Enfant-Morgan papers, Library of Congress, microfilm, Reel I, 23-24.

[47]Digges-L’Enfant-Morgan Papers, Reel I, 26.

[50]Jennifer Schuessler, “Washington’s Tent: A Detective Story,” The New York Times, November 15, 2017, www.nytimes.com/2017/11/15/arts/design/washingtons-tent-a-detective-story.html?_r=0.

[51]“Among His Troops, Washington’s War Tent in a Newly Discovered Watercolor ,” Museum of the American Revolution, www.amrevmuseum.org/virtualexhibits/among-his-troops.

[52]L’Enfant to Washington, February 18, 1782,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07839.

[53]Journals of the Continental Congress, May 2, 1783, 24:324.

[54]Elizabeth Kite, Duportail, 252; George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: L’Enfant to Washington, June 10, 1783, Varick Transcripts, 1775-1785, Library of Congress.

Recent Articles

Teaching About the Black Experience through Chains and The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing

Review: Philadelphia, The Revolutionary City at the American Philosophical Society

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

Recent Comments

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

Sorry I am not familiar with it 2 things I neglected to...

"“Good and Sufficient Testimony:”..."

I was wondering, was an analyzable database ever created? I have been...

"Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards,..."

Thank you for bringing real people, places and event to life through...