I recently drove to Fishkill, New York to see the Daniel Nimham Monument located at the intersection of Routes 52 and 82. Nimham—diplomat, warrior, patriot, and the last sachem of the indigenous Wappinger people—died a violent death in combat on August 31, 1778, at the Battle of Kingsbridge in what now is the Bronx, fighting on behalf of the patriots. The Town of Fishkill dedicated the monument on June 11, 2022.

The dramatic eight-foot bronze monument is mounted on a stone pedestal and sits on a parcel of land shaped like an arrowhead. The monument is highly allegorical. Symbolic features of the monument include a wolf head adorning Nimham’s quiver because he was a member of the wolf clan. In his left hand, Nimham holds a French 1766 pattern military musket from the Charleville armory while in his right hand he is leaving behind a land survey on a tree stump signifying his struggle for native land rights against the Philipse family. The tree stump is a metaphor for a life cut short. His belt has beaded wavy lines to celebrate the ancestral lands of the Wappinger on the Hudson River and secures a tomahawk. A wampum belt recording a treaty between New York and the Wappingers in 1745 is tucked into his belt. Nimham is depicted in linen shirt and trousers and center-seam moccasins decorated with quillwork. He carries a bow, a knife worn around his neck, a powder horn, and a bag for ammunition. Failing to secure justice for his people in the courts, he is taking up arms against the British, hoping that the new American government will restore ancestral land to the Wappingers, a dream that never became a reality.[1]

Daniel Nimham and the Wappingers

Before European contact, the Wappingers lived on the east side of the Hudson River from Manhattan to Dutchess County and in southwestern Connecticut. The word Wappinger may translate roughly as “east of the river.” A different theory is that it relates to the Algonquian word for opossum. European newcomers just labeled the various chieftaincies and bands of Wappingers living along the Hudson as “the River Indians.” Historical documents label them variously as Munsees, Wappins, Wappingers, Opings, Pomptons, River Indians or Stockbridge Indians.[2]

Disease from and warfare against the European colonists decimated the Wappingers. Their population before European contact is estimated at about 13,200 people. By 1700 there were only an estimated 1,000 Wappingers left, and by 1774 only about 300 Native Americans still lived on both sides of the Hudson River.[3]

Into this grim situation for indigenous people, Nimham was born in Dutchess County around 1724. He learned to speak English from neighboring colonists and would go on to soldier in the French and Indian War, on behalf of the British, and the Revolutionary War, against the British; in between these wars, he fought for native land rights.[4]

During the early eighteenth century, the Wappingers still had farms and homes on their remaining land in Putnam and Dutchess counties and rented out land to tenant farmers. The Wappingers sided with the British in the French and Indian War (1754-1763) and moved noncombatants—men too old to fight, women, and children—to the Christian Indian Mission at Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Warriors served admirably in Canada during the war and upon returning to the Hudson Valley at war’s end, discovered that the land-hungry Philipse family, who already controlled most of the land in the area, had confiscated what little ancestral land the Wappingers had left, demanding rents from existing tenants and installing their own tenants.[5]

The Wappinger sought to regain their stolen land through the courts by filing a claim against Philipse heirs Roger Morris, Beverly Robinson, and Philip Philipse to recover 202,800 acres. On March 6, 1765, Nimham presented the legal argument of the Wappingers before Lt. Gov. Cadwallader Colden and a council stacked with powerful New York landlords. Lawyers for the Philipse family produced a bogus deed for the contested property, allegedly signed in 1702 between the Wappingers and Adolphe Philipse that, according to historian Robert S. Grumet, was “hitherto unknown, unlicensed, and unregistered.” Colden and the court, apparently more interested in protecting the interests of the wealthy landlord class than in administering justice equitably, accepted the fraudulent deed as evidence and rejected the Wappinger claim to their ancestral land.[6]

Undeterred, the Wappingers raised enough money to send a delegation to England, which included Nimham and his wife, to argue their case before King George III. The King did not grant them an audience, but they did meet with the Lords of Trades on August 30, 1766, which empathized with the Wappinger claim and criticized Colden’s behavior. Unfortunately, all the Lords did was to order New York Gov. Henry Moore to reconsider the case, which he did on March 10 and 11, 1767. Nimham presented the Wappinger claim to Moore and the same council which had accepted the fraudulent 1702 deed two years before, and with the same result. Moore agreed with the previous decision. Nimham appealed Moore’s conclusion to Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, who declined to support the Wappinger claim.[7]

Swindled out of their remaining lands by royal authorities, the Wappingers returned to Stockbridge and gravitated to the nascent desire for colonial independence from Great Britian. When war broke out in 1775, they sided with the patriots, forming the Stockbridge Indian Company with other displaced natives, commanded by Daniel Nimham’s son Abraham. Daniel Nimham also received a commission as a captain. This sixty-man unit saw service with the Continental Army at the Siege of Boston, Bunker Hill, Valcour Island, Ticonderoga, Saratoga and Monmouth Courthouse. Daniel Nimham distinguished himself as a diplomat by traveling to indigenous nations in the Ohio Valley and Canada to assure neutrality or to persuade them to join the revolutionary cause.[8]

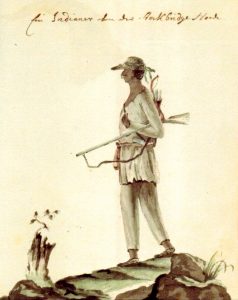

The Hessian Capt. Johann Ewald admired the physicality of the Stockbridge warriors and described their clothing and weapons. “I was struck with astonishment,” Ewald wrote in his diary, “over their sinewy and muscular bodies.” Ewald continued:

Their costume was a shirt of coarse linen down to the knees, long trousers also of linen down to the feet, on which they wore shoes of deerskin, and the head was covered with a hat made of bast. Their weapons were a rifle or musket, a quiver of some twenty arrows, and a short battle-ax which they know how to throw very skillfully. Through the nose and in the ears they wore rings, and on their heads only the hair of the crown remained standing in a circle the size of dollar-piece, the remainder they shaved off bare.[9]

During the summer of 1778, the Stockbridge Company patrolled the neutral ground of Westchester County along with New York State troops. On August 31, they were lured into an ambush on Cortlandt’s Ridge, in today’s Van Cortlandt Park, by Andreas Emmerick, John Graves Simcoe, and Banastre Tarleton. Outnumbered five to one by Emmerick’s Hessians, Simcoe’s Queens Rangers, and Tarleton’s British Legion, the indigenous warriors fought bravely in violent hand-to-hand fighting against the enemy. “The Indians fought gallantly,” wrote Simcoe, “They pulled more than one of the cavalry from their horses.” According to Simcoe, Daniel Nimham “called out to his people to fly, that he himself was old and would die there.” Daniel Nimham wounded Simcoe but fell in the battle, as did his son Abraham. Estimates of indigenous warriors killed at the Battle of Kingsbridge ranged to as high as forty. Ewald examined the dead natives and wrote that “one could see by their faces that they had perished with resolution.”[10]

The Devoe family, which owned the land where the battle occurred, laid to rest the slain warriors in Indian Field, now located in Van Cortlandt Park. They covered Daniel Nimham’s grave with a cairn, a stone mound traditional to Scottish burials. On June 14, 1906, the Bronx Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution erected a large cairn and a plaque to honor Chief Ninham and the Stockbridge indigenous soldiers.[11]

Interview with Michael Keropian, sculptor of the Daniel Nimham Monument

VJD:What is your background?

MK: I have been an artist all my life and have been a military history buff since I was a teen. Grew up in a small town in Connecticut. Prior to graduation from high School I decided to continue studying art and was accepted at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. While my first year was studying every medium of art from drawing and painting to anatomy, I decided to major in sculpture for the next three years. The years at PAFA gave me a great foundation upon which to grow. In 1986, I moved to the Hudson Valley and worked at the Tallix Sculpture Foundry in Beacon, New York for ten years. In 1989 while still at Tallix, I began my own business providing sculptural services to other sculptors. After my foundry days I began teaching and continuing to work on my business and my own sculpture work.

In 2000, I was commissioned to create nine monumental Tiger sculptures for Comerica Park, the new home of the Detroit Tigers baseball team. They are the largest tiger sculptures in the Western Hemisphere.

Since then I have worked on public and private commissions, several of them historical sculptures, as well as providing instruction and sculptural services for other artists.

VJD: How did you learn about Daniel Nimham and what inspired you to undertake this project?

MK: Back in 2000, my wife Jan and I bought a home down the street from Mount Nimham in Carmel, which happens to be the highest point in Putnam County, New York. Native structures were still up on the mountain up until the CCC bulldozed them down in the 1930s to put in a fire road.

While I had some knowledge of the Native People who once lived in this region, it really wasn’t until several local historians came over for a visit, and asked if I would be interested in making a sculpture of Sachem Daniel Nimham for our town of Kent, New York, that I learned about Nimham. So this was enough to inspire me to make a small model of Nimham and learn more about him.

VJD: What did you learn when doing the research for this monument?

MK: While there were no real descriptions of Daniel Nimham, I began collecting and reading any descriptions of Native People from the mid-1700s. One part was depicting Nimham’s possible regalia the other was researching how he may have looked physically. I had read quite a number of references that Nimham and the natives in the northeast were quite tall. So it inspired me to find a collection of skeletal remains to measure. I found a collection of skulls at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. The closest skulls to the Wappingers or Mohican People available in their collection were from the New Jersey area in around the late 1780s. I took the day to photograph them and measure and compare the skulls of New Jersey with those of Native skulls from different parts of North America. This gave me a clue as to the basic structure of an Algonquin skull and thus helped me create the likeness for my small maquette of Nimham. So it was part science and part intuition.

I also visited West Point and discussed with the curators what type of musket Nimham may have been carrying. I was searching for all sorts of regalia, specifically Wappinger and Mohican. As for the composition of the sculpture, I decided early on that a monument for Nimham shouldn’t be depicting him at the Battle of Kingsbridge where he died on August 31, 1778 with his son and about thirty other Stockbridge, and that I should go for something more symbolic and allegorical, to help tell his story. I also contacted a couple descendants from the Nimham/Ninham family looking for some images of descendants. I am actually still doing research and genealogy of the Nimham family.

VJD: What was the best part of the project and how did you feel upon its completion?

MK: Originally the focus of a sculpture of Nimham was supposed to go in here in Kent, Putnam County, New York. But after waiting a couple of years and seeing no effort in fundraising, I began looking for other options. Thinking it was still a worthy project, I began contacting other towns in the Hudson Valley that might be interested enough to fund the project.

In 2012, I presented the project to the Town of Fishkill, New York. After my presentation a man in the audience came up and suggested to the board that this was a worthy project, and they should seriously look into doing it. Unfortunately, they didn’t move on it either. However, in 2020 I received a phone call from the man at the presentation. He had just been elected as Supervisor of the Town of Fishkill, and he wanted to do the project. Supervisor Ozzy Albra felt that Fishkill needed to remember their history and that a sign or plaque was not enough. When Ozzy first met me at the 2012 meeting, he said he had never known who Nimham was.

Daniel Nimham was born not far from where the sculpture is. A plaque with his name dedicated in 1937 was mounted on a rock for decades and few knew about it or read it. I refurbished the plaque, and it is mounted to the front of the stone pedestal supporting the eight-foot bronze sculpture.

The fact that this project became a reality after twenty years is the best part. Today thousands drive by the sculpture daily which is located on a parcel of land shaped like an arrowhead and they do take notice.

As a professional sculptor and artist, the statue of Nimham brings together all the essential elements of creating a great sculpture, an interesting composition with movement, and it is interesting from every view. It has symbolism and historical accuracy, and is allegorical—that helps tell Nimham’s story.

Daniel is striding up a hillside and foresees the future of his people. Leaving behind the deed or land survey (symbolizing his effort to reclaim land in the colonial courts), he then picks up the musket and heads off to fight for the American Cause with the Stockbridge Militia.

VJD: Why do you think the monument is important?

MK: Daniel and the Stockbridge Wappinger and Mohican were some of America’s first veterans and gave their life for this new country. While we had about 400 in attendance at the dedication ceremony, only two local papers showed up. It seems the media is more concerned with sculptures that come down rather than sculptures that go up to American Heroes.

VJD: What does the life of Daniel Nimham teach us?

MK: As the last Sachem of the Wappinger People and a Sachem with the Mohicans of Stockbridge, Daniel’s short life was dedicated to the concerns and future of his people. It is evident that after several attempts in court and even going to England trying to reverse the land fraud here in Dutchess County, that the only recourse was to help the colonists sever their ties with King George. Nimham, his son, and the others were hopeful that if they allied and fought well, that the new country would reward their dedication with lands of their own. Sadly, after their sacrifice they were pushed west to Oneida territory and eventually to Ontario and Wisconsin.

For additional information, see the film The Creation of the Daniel Nimham Sculpture.

[1]Jeff Hodges, The Creation of the Daniel Nimham Sculpture(New York: Parker/Hodges Productions, Inc., 2023), vimeo.com/791442232.

[2]Eugene J. Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” excerpt regarding Daniel Nimham and the Wappingers, 1,web.archive.org/web/20150113053107/http:/www.putnamstonechambers.net/files/Daniel_Nimham_and_the_Wappingers.pdf; Laurence M. Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge: Daniel Nimham and the Stockbridge Indian Company in the American Revolution,” American Indian Magazine, Vol. 18, No. 3 (Fall 2017), www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/road-kingsbridge-daniel-nimham-and-stockbridge-indian-company-american-revolution.

[3]Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” 1, 3.

[4]Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” 1-3; Robert S. Grumet, “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783,” The Hudson Valley Regional Review(September 1992), 81-99;Patrick Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1992), 159-169, 221-223; Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge.”

[5]Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” 4-5; Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, 112, 155;Grumet, “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783,” 89; Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge.”

[6]Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” 4-5; Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, 157-158; Grumet, “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783,” 89; Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge.”

[7]Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, 160-169; Grumet, “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783,” 90; Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge.”

[8]Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge;” Bryan Rindfleisch, “The Stockbridge-Mohican Community, 1775-1783,” Journal of the American Revolution (February 3, 2016), allthingsliberty.com/2016/02/the-stockbridge-mohican-community-1775-1783/; Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, 198.

[9]Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War, trans. ed. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 145.

[10]Ewald, Diary of the American War, 145;John Graves Simcoe, A Journal of Operations of the Queen’s Rangers (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Press, 2018), 40-41; Hauptman, “The Road to Kingsbridge;” Frazier, The Mohicans of Stockbridge, 221-223; Grumet, “The Nimhams of the Colonial Hudson Valley, 1667-1783,” 91; Boesch, “Native Americans of Putnam County,” 4-5.

[11]Van Cortlandt Park: Indian Field, www.nycgovparks.org/parks/VanCortlandtPark/highlights/11610.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...