The “Ten Crucial Days” winter campaign of 1776-1777 reversed the tide of war just when Washington’s army appeared near collapse. Beginning with the Christmas night crossing of the Delaware River, Washington recorded his first three significant victories over the British and their Hessian auxiliaries under the overall command of Maj. Gen. William Howe and the field command of Lt. Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis: on December 26 at the First Battle of Trenton, January 2 at the Battle of Assunpink Creek (or Second Battle of Trenton), and January 3 at the Battle of Princeton. Five overlapping factors loom large when considering these events and offer absorbing analytical value: leadership, geography, weather, artillery, and contingency.

Leadership

Washington’s aggressiveness was balanced by restraint when strategic necessity dictated.[1] Both qualities were exhibited in this campaign. By December 1776, with final defeat seemingly imminent, he was willing to gamble on what he conceded was a do-or-die operation, an assault on the Hessian brigade in Trenton that “necessity, dire necessity will—nay must justify.”[2] On the other hand, the manner in which Washington orchestrated his army’s success in fending off the enemy attack at Assunpink Creek on January 2 has been hailed as a model of a brilliantly managed defensive battle.[3] Making a stand at the creek with his troops’ back to the Delaware River, Washington steered them through arguably the war’s most pivotal moment.[4] He reasoned that his inexperienced soldiery were best equipped to wage a defensive action against a militarily superior Anglo-German force, an opinion he had held from early on: “Place them behind a Parapet—a Breast Work—Stone Wall—or anything that will afford them Shelter, and from their knowledge of a Firelock, they will give a good Account of their Enemy.”[5]

According to Maj. Gen. William Heath, “Gen. Washington exhibited the most consummate generalship” in engineering the resistance at Assunpink Creek and overnight advance to Princeton. “Ambuscade, surprise and stratagem are said to constitute the sublime part of the art of war, and that he who possesses the greatest resource in these, will eventually pluck the laurel from the brow of his opponent.” Echoing Sun Tzu’s The Art of War from the fifth century B.C., Heath asserted, “The stratagems of war are almost minute, but all have the same object, namely, to deceive—to hold up an appearance of something which is not intended, while under this mask some important object is secured.” No matter how brave a general, “if he be unskilled in the arts and stratagems of war, he is really to be pitied, for his bravery will but serve to lead him into those with snares which are laid for him.”[6]

The Princeton victory capped off a plan Washington probably devised prior to the council of war he held late on January 2, after the Assunpink Creek clash, where it was decided to march north rather than retreat south or engage Cornwallis the next morning.[7] By one account, Washington’s end run up to Princeton was a well-planned maneuver that had been scouted for several days and kept secret from most of his officers until the last minute for security reasons, as was done prior to December 26.[8] Washington had indicated his interest in assaulting other enemy outposts: “If we could happily beat up the rest of their Quarters bordering on & near the River, it would be attended with the most valuable consequences.”[9] This interpretation is supported by Pvt. John Lardner of the Philadelphia Light Horse, who accompanied a January 1 patrol along the road the troops would take to Princeton one night later. He recalled that “the Enemy had no patroles there, and that apparently they had no knowledge of it. Along this road Washington led his army the following night, on the memorable retreat, & with which he must have been made acquainted or the patroles would not have been placed there.” Lardner remembered the council of war “on the evening of the 2d Janry, and to have heard it confidently mentioned the next day & repeatedly afterwards as the universal sentiment—that the thought of the movement that night originated entirely with Washington—solely his own manoeuvre.”[10]

By contrast, the leadership of the Crown’s forces during this campaign has been derided, fairly or not, by even some on their own side. Lt. Col. Allan Maclean observed, “Poor devils as the Rebel generals are, they out-generaled us more than once . . . and it is no less certain that with a tolerable degree of common sense, and some ability in our commanders, the rebellion would now be near ended.” He found Howe to be an “honest man, and I believe a very disinterested one. Brave he certainly is and would make a very good executive officer under another’s command, but he is not by any means equal to a C. in C. I do not know any employment that requires so many great qualifications either natural or acquired as the Commander in Chief of an Army.” Furthermore, Howe had “very silly fellows about him—a great parcel of old women—most of them improper for American service . . . it is truly too serious a matter that brave men’s lives should be sacrificed to be commanded by such generals.” Finally, Maclean took aim at Cornwallis, “a brave man, but he allowed himself to be fairly outgeneraled by Washington . . . at Trenton [on January 2-3], and missed a glorious opportunity when he let Washington slip away in the night.”[11]

The British secretary of state Lord George Germain bemoaned Howe’s failure to win a decisive victory. “If the General, in the tide of success which run so strongly in his favor, had followed his advantages properly up, by crossing the Delaware” in early-to-mid-December “and had possessed himself of the province of Pennsylvania, which at that time would have been the consequence of the possession of Philadelphia,” Germain claimed there was “a fair prospect of a successful campaign, and of the happy termination of the war.”[12]

The tactical shortcomings in British leadership appear to have stemmed, at least in part, from underestimating the leadership and competence of Washington’s army, understandable given its prior performance. Archibald Robertson, an officer in the British Corps of Engineers, wrote: “Throughout this whole Expedition [January 2-3] we certainly always erred in imprudently separating our Small Army of 6,000 men by far too much and must hope it will serve as a lesson in future never to despise any Enemy too much.”[13]

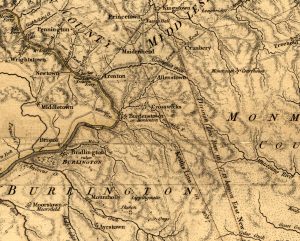

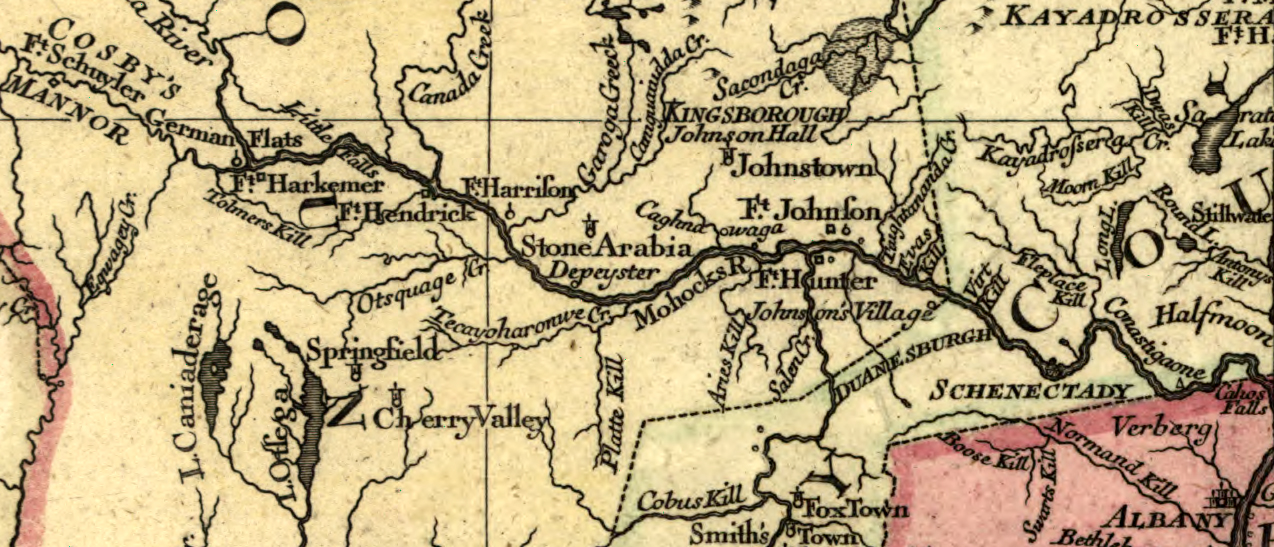

Hessian Capt. Johann Ewald lamented: “Four weeks ago we expected to end the war with the capture of Philadelphia, and now we had to render Washington the honor of thinking about our defense . . . Since we had thus far underestimated our enemy, from this unhappy day onward we saw everything through the magnifying glass.”[14] Ewald faulted Cornwallis for underrating his adversary on January 2 and rejecting the advice of Hessian Col. Carl von Donop, who knew the local terrain better than Cornwallis, to approach Trenton in two columns rather than a single thrust. “This brilliant coup which Washington performed against Lord Cornwallis, which raised so much hubbub and sensation in the world and gave Washington the reputation of an excellent general derived simply and solely from Lord Cornwallis’s mistake of not marching in two columns to Trenton,” according to Ewald. “Had one column marched to Crosswicks by way of Cranbury, the American general would have had to abandon Trenton and still would have remained in a too unfavorable and precarious situation, since he had no depot for his new army in our vicinity.” Ewald explained, “Then Lord Cornwallis would have needed only to pursue him steadily whereby his army, lacking everything, would have been destroyed in a few days. Colonel von Donop suggested to Lord Cornwallis that he march in two columns, of which the left one would go by way of Cranbury. But the enemy was despised, and as usual we had to pay for it.”[15]

Charles Stedman, an American-born officer in the British army, deprecated Howe’s plan for occupying New Jersey, which created an opening for Washington’s winter campaign. Howe ordered his troops into winter quarters on December 14—a string of outposts stretching from Bordentown and Burlington below Trenton all the way to Perth Amboy. “The great and principal error” on Howe’s part that Stedman identified was “dividing his army into small detachments; and those at such a distance from each other, as, in case of attack, not to be capable of receiving immediate assistance from the main army.” In Stedman’s judgment, “it was owing to this injudicious arrangement, that the British army, when in the Jerseys, were . . . cut up in detail. The manner in which he disposed the army into winter cantonments, was particularly blamable.” He noted that “the chain of communication which the British troops occupied from the Delaware to the Hakensack was too extensive, and the cantonments too remote from each other; for the space between the two rivers was not less than eighty miles.” Moreover, the Hessians whom Howe left in forward positions “ought not to have been stationed either at Trenton or Bordentown; for they were the barriers to the Jerseys, and lay nearest to the enemy.” British light infantry should have occupied them, as the German soldiers, “understanding nothing of the language of the country, were unable to obtain proper intelligence, and, instead of conciliating the affections, made themselves particularly disagreeable to the natives, by pillaging them, and taking from them the necessaries of life, without making them an adequate compensation.” To make matters worse, “the four frontier cantonments at Trenton, Bordentown, White Horse, and Burlington, were the weakest, in respect of number of troops, in the whole line of cantonment.” The riverside town of Trenton, “opposite to which Washington lay with the main body of his army, and with boats prepared to cross the Delaware at his pleasure, was defended only by twelve hundred Hessians; and . . . Bordentown, White Horse, and Burlington, by no more than two thousand.” These posts were “left without a single redoubt or intrenchment, to which, in case of a surprise, the troops, until they should be relieved from the other posts, might retreat.”[16]

The decisions of officers in the field contributed to the December 26 debacle as well. Howe pointed to Rall’s failure to fortify Trenton, because if he “had obeyed the orders I sent to him for the erecting of redoubts, I am confident his post would not have been taken.”[17] The report of the Hessian war commission to the Prince of Hesse-Cassel reproached Rall for neglecting “to protect his position by redoubts, where the safety of the village required them,” as he was ordered to do by von Donop, his superior officer.[18] In Rall’s defense, the open country on Trenton’s northern edge rendered it widely accessible and prompted Rall to write von Donop on December 21, “I have not made redoubts or any kind of fortifications because I have the enemy in all directions.”[19]

Other officers were arguably more at fault than Rall for the loss of Trenton, specifically Maj. Gen. James Grant, commanding His Majesty’s forces in New Jersey, and von Donop with his contingent at Bordentown—who apparently failed to perceive a serious threat to Rall’s garrison. Rall repeatedly requested Grant to station a detachment at Maidenhead, halfway between Princeton and Trenton, but to no avail.[20] Grant sought to allay Rall’s concerns, assuring the colonel “that the rebel army in Pennsylvania . . . have neither shoes nor stockings, are in fact almost naked, dying of cold, without blankets and very ill supplied with Provisions.”[21] And two days after Washington’s attack, von Donop wrote Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen, “There was nothing in Colonel Rall’s reports, and more especially in the communications from General Grant to fear at Trenton.”[22]

Perhaps the most egregious error of all was von Donop’s—not being at his post in Bordentown on December 26, but in Mount Holly eighteen miles away and thereby unable to aid Rall. He had responded to an incursion by rebel militia on the 23rd; however, having repelled the intruders, he did not return to Bordentown but instead lingered in Mount Holly, ostensibly to collect food and forage and allow residents to sign an oath of allegiance to the king, but at least by some accounts due to von Donop’s infatuation with a fetching young widow whose identity is unknown. So von Donop, who reputedly delighted in female companionship, positioned his troops more than a full day’s march from Trenton, clearly at odds with General Howe’s intent. According to Captain Ewald, “the utter loss of the thirteen splendid provinces of the Crown of England, was due partly . . . to the fault of Colonel von Donop, who was led by the nose to Mount Holly by Colonel [Samuel] Griffin, and detained there by love . . . Thus the fate of entire kingdoms often depends upon a few blockheads and irresolute men.”[23]

While acknowledging the precarious position in which he placed Rall’s brigade, Howe explained that he had taken it upon himself “to risk that post under the command of a brave officer, with the support of Colonel von Donop at Bordentown,” because the Hessian troops had occupied the left of his troop alignment during their march through New Jersey. To deviate from that positioning in assigning his forces to their winter posts would have reflected badly on Britain’s German auxiliaries and been “considered as a disgrace.” The blame for December 26, the British general contended, should fall on Rall and von Donop, as they were both “perfectly satisfied” with their postings and “had timely information of the intended attack” (both questionable assertions). Moreover, their posts were only “five miles distant” from each other” (more like seven, actually) and “were occupied by nine battalions” with a combined total of “3000 men, with sixteen field pieces” (although the Trenton garrison had only fifteen hundred men and three cannon available when forced to rely on their own defenses). Howe’s “principal object in so great an extension of the cantonments was to afford protection to the inhabitants, that they might experience the difference between his majesty’s government, and that to which they were subject from the rebel leaders.”[24]

Geography

The good news for Howe in December 1776 was that his invasion had penetrated some eighty to ninety miles from the Hudson (then the North) River to the Delaware. The bad news was that he now had to assume the burden of attempting to control such a wide swath of territory. Howe’s decision to disperse his forces so as to protect as many Loyalists as possible overcame his reservations about spreading them too thin. He explained his reasoning to Secretary of State Germain:

The chain, I own, is rather too extensive, but I was induced to occupy Burlington to cover the county of Monmouth, in which there are many loyal inhabitants; and trusting to the almost general submission of the country to the southward of this chain, and to the strength of the corps placed in the advanced posts, I conclude the troops will be in perfect security.[25]

Howe’s concern for shielding Loyalist residents may have been informed by an inflated estimate of just how many there were. Perhaps he was beguiled by the number who signed loyalty oaths to the Crown in response to a proclamation issued by Howe and his brother Adm. Richard, Lord Howe, in their role as peace commissioners, on November 30, 1776. If so, the misleading nature of this impression was recognized by other British officers, such as Col. William Harcourt, who observed shortly therafter “that we have not yet met with ten, I believe I have said two, disinterested friends to the supremacy of Great Britain.”[26]

Aside from the broader geographic realities, the local terrain figured notably on January 2 during the delaying action waged by Col. Edward Hand’s skirmishers along the Post Road from Princeton to Trenton and in the fighting at Assunpink Creek immediately following. The woods dotting the landscape along the narrow Post Road afforded Hand’s marksmen protective cover, and a series of streams offered multiple points at which to create a bottleneck in troop movements—natural impediments to Cornwallis’s advance. The scene was reminiscent of others during war in that its topography generally accommodated combatants waging a defensive action.[27] The broken terrain that characterized most American battlefields often frustrated efforts to maintain a well-connected line of attack.[28]

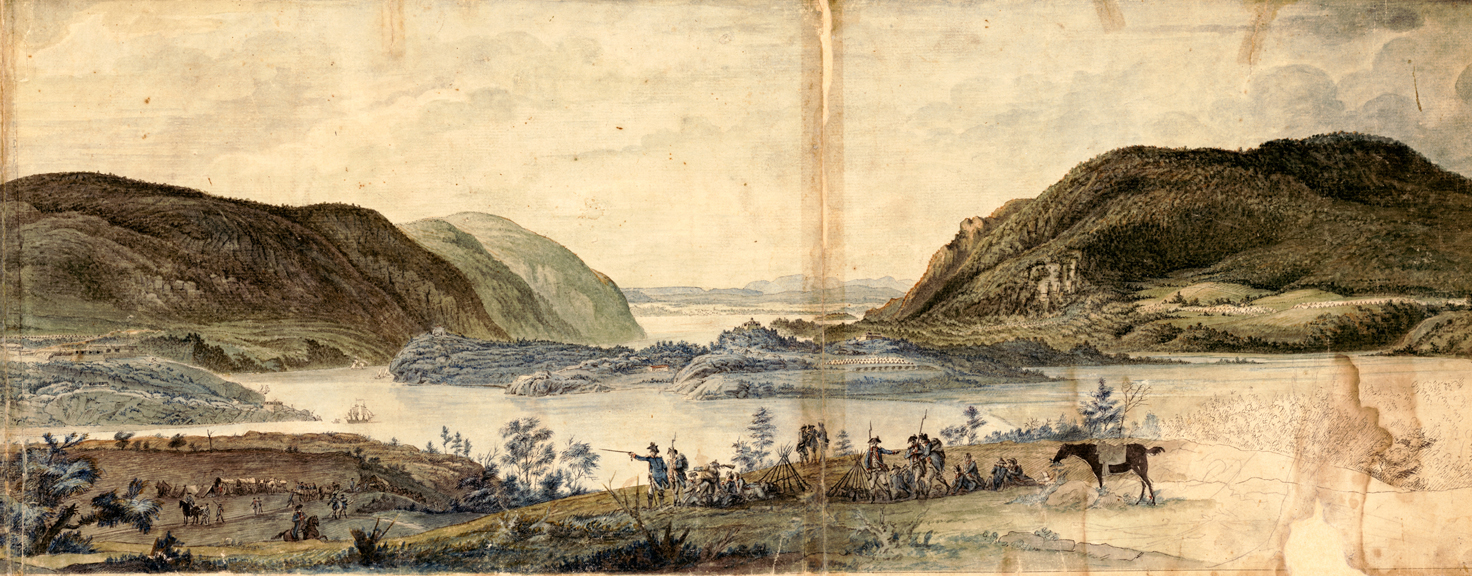

Once the Crown’s forces reached Trenton, they faced another natural obstacle—the Assunpink Creek whose waters were high and swift owing to the snow that had melted due to rain and thaw the previous night.[29] According to Col. (soon to be general) Henry Knox, the creek “in most places [was] not fordable,” and “our army drew up” with its artillery on the high ground “that may be said to command Trenton completely.”[30] British Col. Archibald Robertson observed that the defenders were “exactly in the position” Rall’s brigade “should have taken” when they were attacked one week earlier.[31] From here the Americans rained cannon, rifle, and musket fire down upon the British and Hessian soldiers attempting to cross the narrow stone bridge, and Cornwallis’s suspension of his assault that night allowed Washington’s troops to escape to Princeton.

Weather

Delaware Valley weather proved to be a major factor in the campaign.[32]The First Battle of Trenton was one of those prominent instances in which unexpectedly challenging weather significantly influenced how a battle plan or engagement unfolded, and when the outcome might have been otherwise were it not for the elements.[33]The insurgent forces staged their Christmas night crossing in “weather uncommonly inclement.”[34] A blizzard and ice-choked Delaware River threatened to foil Washington’s attack by preventing two of the three rebel forces from crossing. The weather was, however, a double-edged sword, as it facilitated the element of surprise. Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene conveyed an image of weather and war that suffused Trenton: “It rained, hailed, and snowed and was a violent storm. The Storm of nature and the Storm of the Town exhibited a Scene that filled the mind during the action with passions easier conceived than described.”[35] One of the German officers recounted that “our weapons, because of the rain and snow, could no longer be fired, and the rebels fired on us from all the houses. There remained no other choice for us but to surrender.”[36]

The weather again aided the American cause on January 2. Muddy road conditions from the preceding night’s rain and unseasonably warm temperatures slowed Cornwallis’s march to Trenton long enough to foil his plan of attacking Washington in broad daylight, and that night a twenty-degree drop in temperatures made the ground hard enough to accommodate the American troops and artillery along their backwoods route to Princeton.

Artillery

Cannon were of great consequence during the battles at Trenton and Princeton.[37] The Americans’ success was to no small degree a result of the sizeable advantage they enjoyed in the number of field guns on each occasion. Primary sources concur on the respective totals for the opposing sides at the First Battle of Trenton but vary for Assunpink Creek and Princeton. Taking into consideration the various accounts, the American advantage in field pieces was eighteen to six at Trenton on December 26, forty to twenty-eight at Assunpink Creek, and thirty-five to six or eight at Princeton.[38] Henry Knox reported that his heavy guns numbered ”eighteen field pieces” compared to the enemy’s “six brass pieces” at Trenton and that he had “thirty or forty pieces” at Assunpink Creek.[39] At Princeton, Capt. Thomas Rodney of Delaware’s Kent County militia, observed that “on the hill behind the British line they had eight pieces of artillery.”[40]

Washington accorded a priority to the use of artillery in preparing for the assault on the Hessian garrison in Trenton. His methodical approach to utilizing this arm of the Continental Army is reflected in his general orders of December 25, which were designed to optimize the role cannon would play in the upcoming action. Washington stipulated that Brig. Gen. Adam Stephen’s Virginia brigade was to “form the advanced party & to have with them a detachment of the Artillery without Cannon provided with Spikes and Hammers to Spike up the enemy’s Cannon in case of necessity or to bring them off if it can be effected, the party to be provided with drag ropes for the purpose of dragging off the Cannon.” Stephen’s men were in the van of Greene’s division, which formed the left wing of the army, while Maj. Gen. John Sullivan’s division encompassed the other wing. “Four pieces of artillery to march at the heads of each Column,” the orders specified, with “three pieces at the head of the second Brigade of each Division and two pieces with each of the reserves.”[41]

At Trenton, Greene’s wing occupied a strategically advantageous position above the town and from there continuously rained artillery fire on the defenders. The Hessian cannon were quickly rendered useless as their gunners were shot down or abandoned those pieces.[42] According to Knox, the German soldiers “endeavored to form in streets, the heads of which we had previously the possession of with cannon and howitzers; these, in the twinkling of an eye, cleared the streets.” Moreover, “measures were taken for putting an entire stop to their retreat by posting troops and cannon in such passes and roads as it was possible for them to get away by.”[43] Cannon bore the brunt of the battle when the muskets of both sides were largely rendered useless by dampened cartridges and firing mechanisms, but while the Hessian artillery fired only a few rounds, American field pieces were in action throughout. The proportion of cannon to infantry deployed by the Patriot army was at least three times the normal ratio for the eighteenth century.[44] For Knox, this encounter proved the value of mobile artillery in spearheading an assault, with those guns positioned at the head of each column instead of behind them. Rather than playing a supporting role, his cannon were the driving force in the engagement.[45]

A week later, the American gun crews below the Assunpink Creek delivered the most intense cannon fire that had ever blazed across a Western Hemisphere battlefield.[46] Although the American troops were fewer than Cornwallis’s total force, they deployed some forty field pieces to the enemy’s twenty-eight, placed where they could create overlapping fields of fire. Nearly half covered the bridge at Queen Street—the most obvious crossing point.[47] According to Knox, when “the enemy advanced within reach of our cannon,” the latter “saluted them with great vociferation and some execution. This continued until dark, when of course it ceased, except a few shells we now and then chucked into town to prevent their enjoying their new quarters securely.”[48]

Cannon played as important a role the following day. If not for the pair of 4-pounders deployed at Princeton by Capt. Joseph Moulder of the 2nd Company of Artillery, Philadelphia Associators, the battle might have turned out rather differently.[49] Thomas Rodney alluded to Moulder’s battery when he recalled that “two pieces of artillery stood their ground and were served with great skill and bravery.” He and a small number of men from Col. John Cadwalader’s brigade took cover from the British volleys behind “some stacks and buildings” on the Thomas Clarke farm, from which “we, with the two pieces of artillery kept up a continuous fire on the enemy, and in all probability it was this circumstance that prevented the enemy from advancing.” According to Rodney, “Gen. Washington having rallied both Gen. Mercers and Cadwaladers brigade they moved forward and when they came to where the artillery stood began a very heavy platoon fire on the march. This the enemy bore but a few minutes and then threw down their arms and ran.”[50]

Contingency

A healthy and timely measure of luck accounted in part for the success of the Whig cause that winter. Washington’s good fortune was aided by key determinants over which he had no control, specifically the impact of weather and decisions by opposing officers. These have been explored above, but the reader must decide where to draw the analytical line between serendipity and intentions.

One instance in which Washington and his troops appear to have benefited from a twist of fate actually preceded the “Ten Crucial Days” but arguably set the stage for the commanding general to assert himself as the rebellion’s undisputed military leader. By December 1776, Washington had lost every major battle he had fought and appeared to be an inept and indecisive leader to a growing number of skeptics. Chief among these was his second-in-command, Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, who had lost trust in Washington’s military judgment and aspired to establish his own command.[51] A letter he wrote Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates on December 13 opined, “Entre nous, a certain great man is most damnably deficient.”[52] That same day, Lee was seized by British dragoons at a tavern near Basking Ridge, New Jersey, in what was widely viewed by both sides as a significant setback to the rebel cause due to his impressive military résumé and expertise. However, Lee’s absence proved to be a blessing in disguise for Washington, now able to make strategic decisions without having to fear that Lee, with his more extensive military background and proclivity for dilatory responses to Washington’s orders, would question the latter’s authority. Washington was anxiously waiting for Lee to bring his troops across New Jersey and unite with the former’s dwindling contingent. Lee had been moving at a very deliberate pace, but now his capture facilitated the army’s efforts to come together in a very literal sense, as General Sullivan, his second-in-command, promptly set Lee’s troops in motion. One of those soldiers, Pvt. Jacob Francis of the 16th Continental Regiment from Massachusetts, recalled: “The next morning we continued our march across Jersey to the Delaware and crossed over to Easton. From thence we marched down the Pennsylvania side into Bucks County.”[53] Sullivan arrived in Washington’s camp on December 20 with two thousand desperately needed reinforcements—an essential precondition to any American counteroffensive.

Contingency raises its head in connection with a raid by Adam Stephen’s brigade, without Washington’s knowledge, against Rall’s three regiments on December 25. Stephen dispatched a party of about fifty Virginians to harass the German garrison, and sometime after dusk the Hessian “picket [post] on the Pennington Road was attacked and six men were wounded.”[54] The Hessians pursued the intruders, who escaped in the darkness but remained on the outskirts of town and joined the rest of the army approaching Trenton next morning. Washington was reportedly furious when he learned of Stephen’s action, fearing it dashed his hopes of surprising Rall.[55] Ironically, Stephen may have achieved the opposite effect, although no explicit evidence supports that conclusion. Rall had received an urgent message on the evening of the 25th from General Grant, based on intelligence from spies in Washington’s camp, warning the colonel “to be on your guard against an unexpected attack.”[56] Did Rall assume this raid was the attack about which he had been warned? That his troops did not mount any serious patrol up the river in the early morning hours of the 26th may have been due to the weather more than anything else, but perhaps Rall would have insisted on greater vigilance if not for the foray by those fifty Continentals.

A twenty-first century study asserts that the Battle of Assunpink Creek is a prime example of the role of “happenstance” as a factor in warfare. The premise of this argument stands in sharp contrast to the claim that Washington’s efforts on January 2-3 were informed by a well-conceived tactical plan, and the study’s author admits this claim seems to have been ratified by what actually happened. That said, the author posits that Washington put his men in perilous circumstances that left everything to chance and as a risk-benefit calculation made little sense, leaving the fate of the Patriot troops to an arbitrary turn of events—Cornwallis’s failure to advance on Trenton in two columns, to outflank the Americans on their right and trap them against the Delaware.[57] To this way of thinking, Washington inadvertently but successfully gambled by placing his army, as Capt. Stephen Olney of Rhode Island recalled, “in the most desperate situation I had ever known it [with] no boats to carry us across the Delaware.”[58] Was the payoff due to luck or Cornwallis’s tactical miscalculation?

Multiple instances in this context illustrate the role of chance in determining the outcome of events, which often renders a battle plan the first casualty of battle. As Carl von Clausewitz opined in Vom Kriege (On War), his classic treatise from 1832 on the theory of armed conflict, “In war more than anywhere else, things do not turn out as we expect.”[59] Then again, as baseball legend Branch Rickey averred, perhaps luck is simply the residue of design?

[1]Michael Stephenson, Patriot Battles: How the War of Independence Was Fought (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008), 255-256.

[2]George Washington to Joseph Reed, December 23, 1776, in This Glorious Struggle: George Washington’s Revolutionary War Letters, ed. Edward G. Lengel (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2007), 82.

[3]David Hackett Fischer, Washington’s Crossing (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 307.

[4]Nathaniel Philbrick, Valiant Ambition: George Washington, Benedict Arnold, and the Fate of the American Revolution (New York: Viking, 2016), 82.

[5]Washington to Reed, February 1, 1776, in This Glorious Struggle, 37.

[6]William Heath, Memoirs of Major-General William Heath, ed. William Abbatt (New York: William Abbatt, 1901. Reprint: Sagwan Press, 2015), 96.

[7]William L. Kidder, Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds (Lawrence Township: Knox Press, 2018), 282-283.

[8]Samuel Stelle Smith, The Battle of Princeton (Reprint of 1967 edition, Yardley: Westholme Publishing, 2009), 33.

[9]Washington to John Cadwalader, December 27, 1776, in “Selections from the Military Papers of General John Cadwalader,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 32:1, 1908: 155.

[10]John Lardner to John Smith, July 31, 1824, in William S. Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1898), 442-443.

[11]Allan Maclean to Alexander Cummings, February 19, 1777, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants, eds. Henry Steele Commager and Richard B. Morris (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1967), 523.

[12]Remarks by George Germain, May 3, 1779, in The Parliamentary Register: Or History of the Proceedings and Debates of the House of Commons during the Fifth Session of the Fourteenth Parliament of Great Britain (London: John Stockdale, 1802), 11:392.

[13]Archibald Robertson, Archibald Robertson: His Diaries and Sketches in America, 1762-1780, ed. Harry Miller Lydenberg (New York: The New York Public Library, 1930. Reprint: The New York Times and Arno Press, Inc., 1971), 120.

[14]Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War: A Hessian Journal, ed. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 44.

[16]Charles Stedman, The History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War (Dublin: P. Wogan, P. Byrne, J. Moore, and W. Jones, 1794), 1:251-253.

[17]William Howe, The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe, in a Committee of the House of Commons, on the 29th of April, 1779, Relative to His Conduct, during His Late Command of the King’s Troops in North America: To which are added some Observations upon a Pamphlet, entitled Letters to a Nobleman (London: H. Baldwin, 1780. Reprint: Toronto Public Library), 8.

[18]Report of the Hessian War Commission to the Prince of Hesse-Cassel, April 15, 1782, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 420.

[19]Smith, The Battle of Trenton, 27.

[21]James Grant to Johann Rall, December 21, 1776, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 334-335.

[22]Carl von Donop to Wilhelm von Knyphausen, in ibid., 399.

[24]Howe, The Narrative of Lieut. Gen. Sir William Howe, 7-9.

[25]Howe to Germain, December 20, 1776, in Charles Cornwallis, Correspondence of Charles, first Marquis Cornwallis, ed. Charles Ross (London: John Murray, 1859), 1:25.

[26]William Harcourt to Earl Harcourt, March 17, 1777, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six, 524.

[27]Matthew H. Spring, With Zeal and with Bayonets Only: The British Army on Campaign in North America, 1775-1783 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008), 193.

[29]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 301.

[30]Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, January 7, 1777, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 449-450.

[31]Robertson,Archibald Robertson: His Diaries and Sketches, 119.

[32]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 399.

[33]Don N. Hagist, “Top Ten Weather Interventions,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 2, 2022,

allthingsliberty.com/2022/08/top-ten-weather-interventions/.

[34]William P. McMichael, “Diary of Lieutenant James McMichael of the Pennsylvania Line, 1776-1778,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, 16:2, 1892: 140.

[35]Nathanael Greene to Catharine Greene, December 30, 1776, in The Papers of General Nathanael Greene, ed. Richard K. Showman (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1976), 1:377.

[36]Bruce E. Burgoyne, ed., Enemy Views: The American Revolutionary War as Recorded by the Hessian Participants (Bowie, MD: Heritage Books, 1996), 116.

[37]Jac Weller, “Guns of Destiny: Field Artillery in the Trenton-Princeton Campaign, 25 December 1776 to 3 January 1777,” Military Affairs, 20:1, 1956: 1.

[38]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 404.

[39]Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, December 28, 1776 and January 7, 1777, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 371-372 and 450.

[40]Thomas Rodney and Caesar A. Rodney, Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 1776-1777(Wilmington: The Historical Society of Delaware, 1888. Reprint: Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010), 34.

[41]General Orders, December 25, 1776, in This Glorious Struggle, ed. Edward G. Lengel, 84-85.

[42]Friederike Baer, Hessians: German Soldiers in the Revolutionary War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), 125.

[43]Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, December 28, 1776, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 371-372.

[44]Weller, “Guns of Destiny,” 1.

[45]Mark Puls, Henry Knox: Visionary General of the American Revolution (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2008), 78.

[46]William M. Dwyer, The Day Is Ours!: November 1776 – January 1777: An Inside View of the Battles of Trenton and Princeton (New York: The Viking Press, 1983), 324.

[47]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 301.

[48]Henry Knox to Lucy Flucker Knox, January 7, 1777, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 450.

[49]Richard M. Ketchum, The Winter Soldiers (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1973), 360.

[50]Rodney, Diary of Captain Thomas Rodney, 35-36.

[51]Phillip Papas, Renegade Revolutionary: The Life of General Charles Lee (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 202.

[52]Charles Lee to Horatio Gates, December 13, 1776, in The Spirit of ‘Seventy-Six, 500.

[53]Jacob Francis, Military Pension Application Narrative, in The Revolution Remembered: Eyewitness Accounts of the War for Independence, ed. John C. Dann (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), 394.

[54]Report of the Hessian War Commission, in Stryker, The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, 420.

[55]Fischer, Washington’s Crossing, 231-233.

[56]James Grant to Rall, December 24, 1776, in the papers of Colonel Carl von Donop, quoted in ibid., 203.

[57]Stephenson, Patriot Battles, 259-261.

[58]“Captain Stephen Olney, Memoir,” in Biography of Revolutionary Heroes: Containing the Life of Brigadier Gen. William Barton, and also, of Captain Stephen Olney, ed. Catharine R. Williams (Providence: 1839), 193-194.

[59]Carl von Clausewitz, On War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008), 193.

7 Comments

I recommend you to be the technical advisor on the subject when a good film/mini series is finally made. Hopefully much better than the Mel Gibson film. Much potential in the material here.

Thanks, Gunter. The movie that came to mind was “The Crossing” with Jeff Daniels.

David, this is a great overview, and thank you for including Donop at Mount Holly. This is often left out or only mentioned as a footnote. If he had been at Bordentown, who knows how Trenton would have turned out. The action at Petticoat Bridge on December 22, albeit brief and small, is what set in motion the entire chain of events. It is why I no longer believe “Ten” is accurate. It should be Fourteen Crucial Days.

Thanks, Adam. FYI the article really amounts to a lengthy abstract for a manuscript that will obviously go into considerably more detail on every aspect of this and hopefully eventuate in another TCD book. (At this point, I thought I had beaten that horse to death, but now I’ve exhumed the body and am beating it some more.)

My neighbor Adam Zielinski will confirm people in in the area remember this event. There is a sign on the road to Petticoat Bridge, another sign at the house with the skirmish, another sign on the Mount itself, a display at the cemetery a mile away, sometimes a parade with soldiers in uniform “occupying” the town and a mock battle.

David!

Great article. Thanks. I always think of luck when I hear contingency. A fancier term. I’ve stressed luck on my tours.

I would add what I consider another example of luck in the battle of Trenton. I contend that it was luck that Ewing didn’t / couldn’t cross. If he had, being so much closer to Trenton and its outposts than Washington’s crossing, I believe that the sentries would have spotted the Americans and sounded the alarm.

Rall would have formed his troops, probably on the high ground behind the Assunpink, to counter that thrust. Washington would have then encountered that when his troops arrived in Trenton. Much like Cornwallis at 2nd Trenton. That would have drastically changed the first battle, making it much harder for an American victory.

Your thoughts, please.

Bill

I think you’re absolutely right, Bill – that’s a point I make in the manuscript I’m working on that’s a very extended version of the article. Thanks for your comments, as always.