When one mentions the Battle of Petersburg in Civil-War-centric Virginia, the immediate reaction is Ulysses S. Grant versus Robert E. Lee in 1864 and 1865. True. But the first Battle of Petersburg was a revolutionary encounter on April 25, 1781, between the Americans and their British adversaries. And instead of Grant and Lee, the leaders were American Maj. Gen. Baron von Steuben and British Maj. Gen.William Phillips.

And there was a Benedict Arnold connection. Arnold, forty years old and now a British brigadier general, had arrived in Virginia with 1,500 men in late 1780 to raid and to cut off men and supplies to Major Gen. Nathanael Greene, farther south. Steuben reacted by moving stores from Richmond, Petersburg, the Westham Foundry, and Chesterfield farther westward.

Arnold landed at Westover Plantation on the James River on January 4, 1781, and marched west to attack Richmond, the new capital of Virginia, where a small skirmish occurred. Arnold offered to spare Richmond if Jefferson surrendered tobacco stores to the British, but Jefferson refused.

Arnold then burned warehouses, public and some private buildings, and sent Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe and 400 men to destroy the foundry works, powder magazines, and ordnance repair shops at Westham Foundry on January 7. Arnold raided Charles City on January 8, returning to Westover and departing for winter quarters at Portsmouth. American Brig. Gen. Peter Muhlenberg and Arnold shadow boxed in small skirmishes from January through March. But Arnold never attacked Petersburg, as expected.

On March 20, 1781, Maj. Gen. William Phillips and 2,000 troops arrived at Portsmouth to reinforce Arnold and take overall command. Arnold had requested reinforcements, but it is unclear if he expected a more senior officer to arrive as his replacement. With the arrival of Phillips, the stage was now set for battle of Petersburg.

William Phillips, fifty, was an excellent artilleryman, who, by British army policy, supposedly could not command infantry. But he did. A close friend of Clinton, he was a strong disciplinarian, an excellent tactician, and, despite a vile temper, a good leader, esteemed by his soldiers.

Jefferson described Phillips as “the proudest man of the proudest nation on earth.”[1] Gen. William Heath had earlier arrested Phillips, while a prisoner, for being so offensive. His artillery had killed Lafayette’s father at the 1759 Battle of Minden. Phillips was “A model for artillerymen to imitate in gallantry, ability, and progress.”[2]

During the Saratoga campaign of 1777, the British were seeking a way to push the American garrison out of Fort Ticonderoga, New York and adjacent Mount Independence, Vermont. Nearby Sugar Loaf Hill, also known as Mount Defiance, was so steep that the Americans felt it was safe to ignore. But Phillips supposedly said, “Where a goat can go, a man can go, and where a man can go, he can drag a gun.”[3] He did, muscling two 18-pound guns up the slope, causing the Americans to evacuate their defenses and retreat.

Why did Phillips want to go to Petersburg? Why was Petersburg a target? According to the city of Petersburg’s description, there were three reasons:

• It was a central location astride both water and land routes. A transportation hub.

• It was a transfer and storage location for tobacco, which was a medium of exchange, and a repository of much of the wealth of the region. Fully one third of all Virginia tobacco went through Petersburg. Tobacco was basically coin of the realm. The town was far more important than Richmond as a port.

• It was storage and shipping point for military supplies to the American army fighting the British in the southern theater of operations. Protecting and moving those supplies was Steuben’s main job in Virginia, along with raising troops.[4]

Frederick Wilhelm Augustus von Steuben, fifty-one, was a Continental Army major general and its inspector general. He was previously an infantry and staff captain in the Prussian army, but he was not a lieutenant general, as advertised. He is recognized for his training the troops at Valley Forge. Private Ashbel Green said of him, “He seemed to me a perfect personification of Mars. The trappings of his horse, his enormous holsters of his pistols, his large size, and his striking martial aspect, all seemed to favor the idea.”[5]

He was well thought of by Washington and was sent south with Greene, remaining in Virginia. But Steuben was not well liked there, in constant conflict with the civil authorities. Lafayette wrote, “The baron is so unpopular, that I do not know where to put him.”[6] He would command a division at Yorktown. One of his favorite culinary delights was black snake.

American second in command, Peter Muhlenberg, forty, was a Lutheran clergyman from the Shenandoah Valley and a Continental Army brigadier general. Initially commanding the 8th Virginia Continental Infantry, he saw action at Brandywine, Germantown, Monmouth, and Yorktown. After winters at Valley Forge and Middlebrook, he was sent to Virginia, where his role was to support Steuben. He was regularly involved in the patriotic pastime of quarreling over rank with his fellow generals.

On April 18, the British force departed Portsmouth. Moving along the James River, they raided at Burwell’s Ferry, Williamsburg, and Chickahominy between April 18 and 22, disrupting logistics to assist Cornwallis in the Carolinas. Governor Jefferson responded by calling out the militia from nine counties to muster at various locations. The militia represented the only forces available to stop the enemy, as there were no organized Continental regulars in the area. Col. William Davies evacuated Chesterfield Courthouse depot on April 22.

On April 24, after dispersing to raid, the British army reunited at City Point at the confluence of the James and Appomattox Rivers, about ten miles from Petersburg. Here they camped and reorganized. April 25 dawned clear and warm. The original plan was to seize stores at Prince George Court House, but intelligence revealed that most stores had been moved. Hence Petersburg became the target.

During this time, Muhlenberg had been shadowing the British on the south side of the James River, but determining that Petersburg was the target, he marched his force there. Militia Brig. Gen. Thomas Nelson had been covering the north of the river. Nelson, described as a “jovial fat man . . . alert and lively for his size,” was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and would shortly succeed Jefferson as governor.[7]

Muhlenberg entered Petersburg late on April 24, crossing the Appomattox to the heights north of the river.“There was a great counciling that night with our general and field officers, and the conclusion was to fight and try the militia.”[8] Frederick Geon, an African American soldier, described conditions in Petersburg thusly: “There they found great confusion. The inhabitants flying in every direction and our troops were ordered to form.”[9] By the morning of April 25, most of the militia had re-crossed into Petersburg.

When the British destination became clear, Steuben determined to stand at Petersburg. Given that his force was entirely militia, he was not optimistic about victory. His main concern was to avoid being defeated or cut off from the north. He would hold as long as possible, then retreat. Make a good show of it. That was his battle plan.

Why did Steuben choose to defend Petersburg? He wrote:

Being obligated to send large detachments to the neck of land between Appomattox and James Rivers, I had not more than 1000 men to oppose the enemy advance. In this critical situation there were many reasons against risking a total defeat. The loss of arms was a principal one, & on the other hand to retire without some show of resistance would have intimidated the inhabitants and have encouraged the enemy to further incursions. This last consideration determined me to defend the place as far as our inferiority of numbers would permit.[10]

How did the common militia soldier feel? Militiaman Daniel Trabue, soon to be involved in the action, offered, “The backwoods rifle men had been grumbling and scolding about so much retreating and no shooting. They would rather fight than run so much.”[11]

A key element in Steuben’s plan was control of the Pocahontas Bridge, a fifteen-foot wide by thirty-five-foot long arched wooden span over the Appomattox River—the only one in the area. He placed all his artillery, baggage, and cavalry on north side of river. Steuben picked the positions for the troops to defend, and Muhlenberg, more familiar with the units, assigned the troops to these positions.

The British column marched out of City Point at about 10 AM. The route was vulnerable to ambush, but none occurred. Phillips sent eleven small boats up the Appomattox River, parallel to his march down River Road, to carry ammunition and supplies, plus small cannon and a few companies of 76th and 80th Regiments.

American pickets out two miles on river’s north side sighted the British boats at 11 AM at Point of Rocks and gave a harassing but ineffective fire. A body of about 100 Culpeper men, also on the north side of the river, delivered harassing fire again at noon closer in. Steuben now knew the British were near.

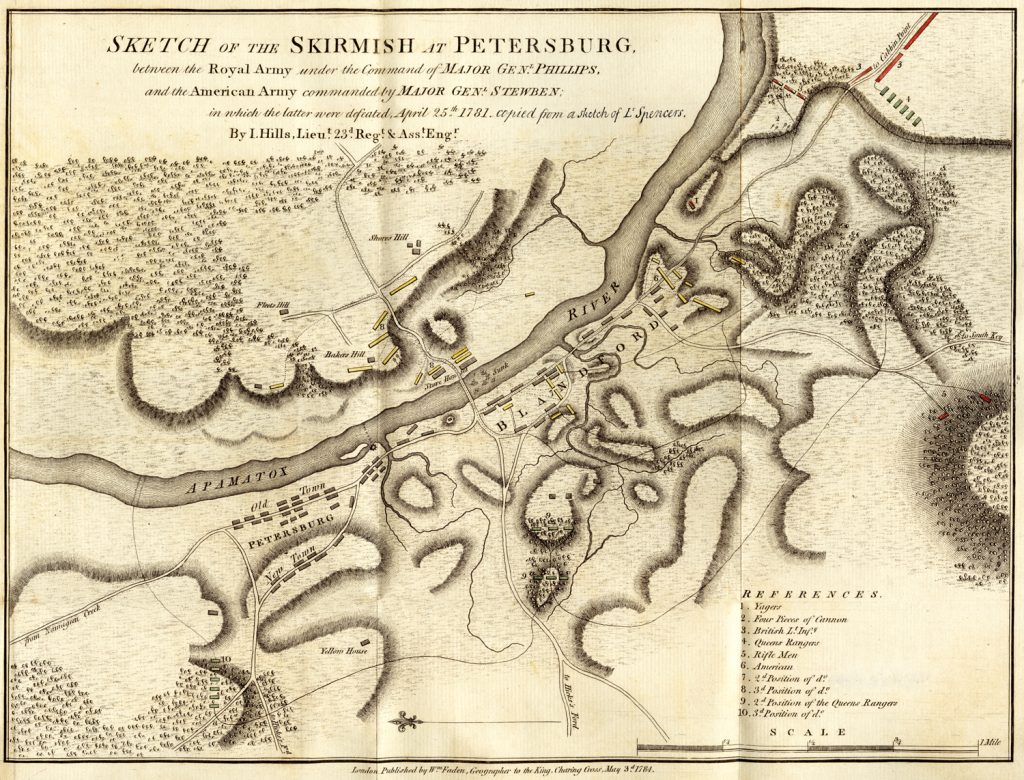

The initial British approach was on the River Road, essentially the current railroad bed. At 2 PM, Phillips stopped his advance, rested his troops, and formed into battle lines about one mile from Blandford, at current East Washington Street and Puddledock Road. The battlefield area was made up of current Petersburg and Blandford. His battle plan was very detailed and thorough.

General Phillip’s main line consisted of the 1st Battalion of Light Infantry and fifty Jaegers under Lt. Col. James Abercrombie on the right, assigned to attack the American left via River Road. The 76th and 80th regiments under Lieutenant Colonel Dundas on the left were to attack the American right. Both frontal assaults were meant to push the Americans towards the river.

Phillips held the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry, the Queens Rangers, the New York Loyalists, and four cannons under Captain Edward Fage in reserve. His entire force numbered about 2,500. He knew that he faced militia, but would be surprised at their steadiness and was concerned about a frontal attack as the battle progressed.

General Steuben had between 1,000 and 1,200 militia men (sources cite conflicting numbers), with essentially no bayonets. The British had a ten to one bayonet edge, but terrain favored the Americans, with gullies and creeks. British bayonets would never really be a factor. Importantly, many of the militia had prior experience in Continental Army regiments.

The American first line was on the bluffs over Poor’s Creek, at the east edge of the town of Blandford. Lt. Col. Thomas Merriweather’s battalion held the left, and Lt. Col. John Dick’s battalion covered the right. The entire line extended from the river to West Hill. Pickets were posted in front.

The second line ran along current Madison Street, with Lt. Col. Ralph Faulkner’s battalion on left and Lt. Col. John Slaughter’s on right, stretching to the Bollingbrook estate, about one half mile east of bridge on the edge of Petersburg.

Approximately 800 troops manned these two lines, with one half mile separation, through which ran a stream called Lieutenant Run. That gap was mainly low ground, grassy pastures, marshes, with the Lieutenant Run causeway and the Blandford Bridge on left. There were no forts or out works, with the defenders using gullies and creeks as obstacles.

Steuben’s third line consisted of a small battalion as the Appomattox River bridge guard, on the north side of the river. Two 6-pound guns were emplaced north of the bridge on Baker’s Hill to cover the valley and nearby ford, along with a small cavalry force. Three infantry companies protected the south side of the bridge.

Earlier in the day, Steuben had ordered a local merchant to give a gill of rum each to the troops and a pint to the officers. Trabue cheered, “Now, boys, drink and fill your canteens. But don’t drink too much. We are going to fight today.”[12]

Initiating the action, Phillips sent Abercrombie against an advanced position on the Wells Hill near Poor’s Creek. The Jaegers quickly drove the militia off the hill. Phillips then dispatched Simcoe to flank the American right with 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry, the Queen’s Rangers, and some Jaegers. His objective was to skirt the American second line and to capture the bridge and ford on the Appomattox. This movement seemed like a possible role for Arnold, as second in command and a general officer. But the job went to Simcoe, who moved behind Wells Hill, concealed from the Americans. It put him and his column temporarily out of the fight.

The British main line now advanced against the American first line, with the militia holding and trading volleys and counter attacking the British right. Phillips’ small fleet on the Appomattox provided supporting fire, hitting Merriweather’s flank. American troops on both sides of the river then counterattacked and stopped the boats. American Captain Epperson on the Petersburg side of the river called out “Shot” when ships’ cannons were fired, and his men would lie down, allowing the balls to go over their heads. British artillery also supported the attack, with Captain Fage’s guns now on the main line laying down covering fire from between the two British wings.

The first American line, after holding for about a half hour, fell back in an orderly fashion for about one quarter to one half mile through Blandford Town, destroying the Blandford bridge as they retreated. The pursuing British formations were broken up by the town’s buildings as they moved through Blandford. American artillery across the Appomattox under sounded off with an ineffective barrage.

Phillips reformed his troops on far side of Blandford Town, with his line parallel to current Crater Road, and launched a frontal attack across the valley, against the four militia battalions. But heavy musket fire from the higher ground stopped the initial and a subsequent assault.

This second line held for about an hour. American Private George Connolly said “according to expectations, the enemy appeared across the creek opposite the town and commenced firing upon our army which had formed to receive them along the opposite side of the creek.”[13] Connolly would suffer both arm and leg wounds, but survive.

Phillips, the old artilleryman, sighted a commanding position and had emplaced the four British guns on the high ground on his left, near current East Washington and Little Church Streets. They opened fire, enfilading the American second line. This turned the tide of the action.

Steuben now ordered Muhlenberg to withdraw to the bridge. Meanwhile, Simcoe had arrived on high ground south of Petersburg, saw the retreating militia, and concluded that he was unable to get to the bridge before the Americans, so he moved west, then north attempting to flank the artillery. American cannon fire drove him back, effectively ending his role in the action, although some of his troops did attack the bridge in the confusion.

The militia retreated in echelon through Petersburg, supporting each other, fanning out at the bridge, using warehouses and buildings for cover. Lt. Colonel Goode’s battalion provided support, but American artillery fire from Baker’s Hill offered little assistance, as troops were too bunched up. The British forces pursued all along the lines, but were broken up by the town, and their charge was driven back. The militia retreated across the bridge, pulling up the planks behind them. A British assault at the bridge was successfully driven back.[14]

British artillery soon turned an orderly retreat into a rout on far side of bridge, as militia moved through a quarter mile of Pocahontas to Shore and Baker’s Hills across the river. American John Banister observed, “As they ascended to the heights, by the Shore’s house, the enemy played their cannon with such skill, that they killed and wounded ten of our men.”[15]

Trabue, who wanted a battle, wrote, “My rifle was so hot that I could hardly hold it. If I were to spit on it, it would fize. Our militia that day were very brave.” He drank his entire canteen of rum, claiming, “I was duly sober. Most of the men did about the same.”[16]

Steuben never employed his reserves. The British entered Petersburg about 5 PM; all action was over by 6 PM. As with many revolutionary battles, no firm casualty numbers exist. Peckham’s Toll of Independence lists only ten Americans killed. Other more realistic sources claim 17 killed, 50 wounded, 125 to 150 captured on the American side. The British reported only 25 to 30 losses. No sources agree. Boatner wrote that both sides lost 60 to 70 total “in this creditable little action.”[17]

The American forces briefly camped at Baker Hill, then retreated seven miles north to Chesterfield Courthouse. Steuben wrote to Greene, “I must confess that I have not yet learnt how to beat regular troops with one third their number of militia.”[18]

An interesting question is just what was General Arnold’s role at Petersburg. All his biographers provide essentially no coverage of Arnold at the battle. Apparently, he played no major part. Why?

Here are three possible explanations. First was that Arnold may have feared capture, causing him to avoid that possibility. Gov. Thomas Jefferson had offered 5,000 guineas for his capture. General Washington told the Marquis de Lafayette, on his way south to Virginia, to hang him if captured, with no trial, court martial or hesitancy. When asked by Arnold what Americans would do if they captured him, a prisoner replied, “They would first cut off that lame leg, which was wounded in the cause of freedom and virtue, and bury it with the honors of the war, and, afterwards hang the remainder of your body in gibbets.”[19] But Arnold, who had been raiding in Virginia since late 1780, never showed anything but courage in battle, from Quebec to Connecticut to Saratoga to Virginia. Hence, such fear seems very unlikely.

The second consideration is that, given the limited nature of the battle, there was no real need for Arnold, as second-in-command, to exercise much of an active role. The flanking movement seemed like a possible assignment.

The third and most likely reason for Arnold’s absence is his relationship with General Phillips and British uncertainty about their new general. Arnold and Phillips had faced each other at Saratoga, where the former was a key player in the American victory and the latter surrendered as part of the Convention Army. They were now British colleagues, but we can only speculate as to Phillips’ view of his new subordinate.

Even Gen. Henry Clinton, the British commander in America, seemed uncertain about Arnold. When he sent him to Virginia, Clinton had given Arnold instructions that he should confer with his seconds-in-command Lt. Col. Thomas Dundas and Lt. Col. John Graves Simcoe before “undertaking any operation of consequence.” These two were given secret dormant commissions, allowing them to replace Arnold if the circumstances warranted such action.[20]

After the battle, Phillips confiscated 4,000 hogsheads of Petersburg tobacco, which he burned in the streets to spare the civilian warehouses. He and Arnold occupied Mary Bolling’s house. When Mrs. Bolling complained about her situation, Arnold warned her not irritate Phillips, as “He was a man of ungovernable temper.”[21]

The British marched north across the repaired bridge on April 27. By now, American militia was scattered in retreat and no longer a threat. On that day Phillips burned the Chesterfield Courthouse base, site of a training depot and general rendezvous for recruit replacements for the southern army. Destroyed were a hospital, storehouses, magazines, sixty log barracks. Arnold detoured to Osborne’s Landing on the James on April 27, destroying much of the small Virginia navy and capturing 2,000 hogsheads of tobacco.

The reunited British force then marched to Richmond, site of Arnold’s earlier visit, arriving on April 30, only to discover that Lafayette had arrived the day before. Unwilling and probably unable to cross the James and assault the heights against Lafayette’s regular Continentals, the British burned Manchester, on the south side of the river. Phillips supposedly then “fell into a violent passion and swore vengeance against me [Lafayette] and the corps I had brought with me.”[22]

Phillips now received orders to return to Portsmouth, but these were soon changed, sending him back to Petersburg to await Lord Cornwallis coming from North Carolina. Lafayette closely followed, cannonading Petersburg from Baker’s Hill on May 10 with two cannons. This was a diversion, allowing Steuben to move a large supply of ammunition across the James, farther up river to go to Greene. Why there were no British forces on the hill remains a mystery.

General Phillips now complained of a “teasing indisposition.”[23] He died at Bollingbrook on May 13 from bilious fever, malaria, or typhus. Speculation varies. He was buried at night in Blandford Church yard, in a still unmarked grave to avoid detection. Supposedly Old Molly, the Bollings’ African American servant killed during the bombardment, was buried over him as subterfuge. A marker to Phillips now stands in the church yard.

Lord Cornwallis arrived from North Carolina on May 20 and took command of the combined forces. Arnold returned to New York City, on orders from Clinton. He proceeded to England in December.

Cornwallis predicted that “I shall now proceed to dislodge Lafayette from Richmond and with my light troops to destroy any magazines or stores in the neighborhood, which may have been collected, either for his use or for General Greene’s army.”[24]

A campaign of marches and counter marches, with clashes at Spencer’s Ordinary and Green Spring, ensued, doing little except forcing Lafayette to retreat, keeping a step ahead of the British. It would end in Yorktown six months later.

What was the significance of the battle? It was certainly not a turning point and did not save the revolution. It did delay Phillips’ movements and probably saved Richmond from another raid, as Lafayette was present when the British returned on April 30. Steuben had given Lafayette time to defend the town and stop a second attack on the capital. Petersburg also showcased the militia, who performed well as they had at Bunker Hill, Springfield, New Jersey, and Cowpens, South Carolina. John Banister lauded them, writing, “This little affair shows plainly the militia will fight.”[25] At best, the battle of Petersburg was an interesting revolutionary side event.

(Thanks go to the late Robert P. Davis and James H. Ryan, both experts on the battle. They were kind enough to share their expertise, both written and oral.)

[1]Robert P. Davis, Where a Man Can Go: Major General William Phillips, British Royal Artillery, 1731-1781 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), xi.

[2]Mark M Boatner, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (New York: David McKay Company, 1975), 865.

[3]Davis, Where a Man Can Go, xvi.

[4]“Revolutionary Petersburg: A Driving Tour” (City of Petersburg, VA: 2008). This brochure with descriptions, illustrations, and maps is excellent. Unfortunately, it is out of print and not likely to soon be reprinted.

[5]Joseph H. Jones, ed., The Life of Ashbel Green, V.D.M. (New York, 1849), 109.

[6]Stanley J. Idzerda, ed., Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution: Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790, vol IV, April 1, 1781 – December 23, 1781 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981), 188.

[7]Boatner, Encyclopedia, 777. Lynn Montross described Nelson and Benjamin Harrison as the “two jovial fat men” of Congress.

[8]Chester Raymond Young, ed., Westward into Kentucky: A Narraative ofDaniel Trabue (Lexington: The University Press of Kentucky, 1981), 95.

[9]Frederick Geon Pension Application, SCAR Pension Applications. His name appears variously as Geon, Gowen, and Going.

[10]Dennis M. Conrad, ed., The Papers of Nathanael Greene (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 8:147.

[11]Young, Westward into Kentucky, 100.

[12]Harry M Ward, Invasion: Military Operations near Richmond, 1781 (Richmond, no date), 20.

[13]George Connolly Pension Application, SCAR Pension Applications.

[14]In 1911, the Appomattox River was diverted to the north of Pocahontas Village, leaving the historic bridge area as a back water. This makes following the flow of the battle extremely difficult. Additionally, local historic markers have not fared well.

[15]John Banister to Theodorick Bland, May 16, 1781, City of Petersburg Museum Archives.

[16]Young, Westward into Kentucky, 102.

[17]Boatner, Encyclopedia, 856.

[18]Conrad, The Papers of Nathanael Greene, 8:267.

[19]Nathaniel Philbrick, In The Hurricane’s Eye (New York: Viking, 2018), 33 and 289. There are a number of variations on this quote.

[20]Carl Van Dorn, Secret History of the American Revolution (New York: Viking, 1941), 419.

[21]Henry Howe, Historical Collections of Virginia (Charleston, SC: Babcock, 1845), 244.

[22]Idzerda, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 4:82.

[23]Davis, Where a Man Can Go, 177. Phillips wrote this in a May 6, 1781 letter to Charles Cornwallis.

[24]Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America, 343. Cornwallis wrote this in a May 26, 1781 letter to Henry Clinton.

7 Comments

Great article on oft forgotten battle. And nice use of the map by Lieut. John Hills! I wasn’t aware of the battle myself until I discovered his map.

Thanks for your interesting article. When writing some years ago about Muhlenberg, I was surprised how little researched seemed to have been done into these actions in Virginia, and it’s good to see it getting some attention.

Bill,

Sorry I didn’t post sooner to pass on appreciation for this article. After failures to deter Arnold’s previous raid up the James River, the militia’s determined stand and organized withdrawal at Blanford/Petersburg was an essential confidence builder. Establishing the Virginia militia as a legitimate force paid dividends throughout the summer of 1781 and enabled both the Marquis and Nathanael Greene a greater degree of confidence in their support. You rightly point out that, as a body, Virginia’s 1781 militia had a large proportion of former Continental soldiers who lent that confidence. Well done, sir!

A small correction: previous pamphlets and publications incorrectly identify John Dick as commander of the American flank. That assertion has caught out others, too. Primary source research has positively determined that flank commander as Major Alexander, “Sawney”, Dick (Sawney being a Scottish nickname based on the brogue pronunciation of Alexander). Sawney was a Virginia Marine, captured in the Caribbean and sent to Forton prison (near Portsmouth, England) as a POW. Dick escaped, had a brief connection with John Paul Jones, then returned to Virginia, where he engaged in that “patriotic pastime” of recovering promotions lost during his two-and-a-half-year absence from Virginia. Dick’s correspondence with Jefferson, Nelson, Steuben and others was captured by Harry Ward in his short study on Sawney Dick included in his compilation “For Virginia and Independence” (McFarland & Co, 2011, pps 9 – 23). Harry included the primary source references, so I won’t repeat here. Again, a minor comment on which other secondary sources led you astray; and only mentioned because “Sawney” deserves credit as an unsung revolutionary hero.

Best wishes!

Jim,

Thanks for both the comments and the correction. Glad to get that important name correct. I must confess to not having looked at Harry’s book. He would correctly chastise me for that omission. He was a great friend, and I still miss him. And a great researcher, historian, and writer. Thanks again. And Huzza to Swaney!

Bill

Interesting article, Bill. Never heard of this action (probably because I am so early-war and Northern army focused), so I am glad you were able to bring it to my and other JAR readers’ attention.

Thanks, Phil.

Nice article Bill, on a little known battle.