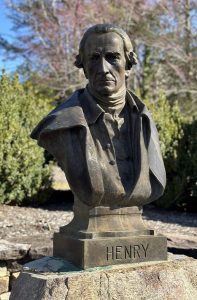

Hanover County, Virginia is the birthplace of one of the most famous American patriots: Patrick Henry. He spent much of his life in and around Hanover. It was in this county that he learned to practice law, which would make him famous in his own time, as well as the eloquent oratory that would make him famous through centuries. The Road to Revolution Heritage Trail runs through Hanover County, marking several landmarks associated with Patrick Henry’s life.

Polegreen Church

Polegreen Church started

as a meeting location for religious dissenters who did not wish to attend the Anglican church. The Rev. Samuel Davies, the first non-Anglican minister licensed by the colony of Virginia, was the pastor of this church from 1747 to 1759.[1] He moved to Virginia at the request of nearly 150 families due to his widespread fame.[2] Not only was he fiercely engaged in the battle for religious tolerance,[3] but as an ardent patriot, Davies encouraged recruitment and service during the French and Indian War,[4] earning him the admiration of Gov. Robert Dinwiddie.

Patrick Henry’s mother attended church at Polegreen, and while he was of the Anglican faith, he often drove her to hear Davies preach. Henry greatly admired Davies’ sermons and adopted many of the same oratorical techniques that later he used with great success as a lawyer, militia commander, and public servant. Throughout his life, Henry acknowledged that his success as a speaker was due to the eloquence he learned from Davies.[5]

Though Polegreen Church was destroyed during the Civil War, sketches of the original building survive. It is from these that the framework of the church has been rebuilt as an open structure. The site hosts a timeline of religious freedom in the United States and is available for tours and special events.

Hanover Tavern

Hanover Tavern was built in the 1750s, and like many taverns of its day was both a place to rest and eat, and also to conduct important social gatherings. Located in proximity to the Hanover County Courthouse, people in town for legal business frequently stayed at the tavern. Patrick Henry’s father-in-law, John Shelton, owned the Tavern.[6] After the store Patrick owned went bankrupt, he and his family moved to the Tavern, where he both lived and worked. Between bartending and playing the fiddle for the patrons, he debated with lawyers and dispensed legal advice despite his lack of professional training. Gaining some notoriety for his articulateness and learning a little about the legal profession through this experience, Henry went to Williamsburg in 1760 to obtain his license to practice law.[7]

like many taverns of its day was both a place to rest and eat, and also to conduct important social gatherings. Located in proximity to the Hanover County Courthouse, people in town for legal business frequently stayed at the tavern. Patrick Henry’s father-in-law, John Shelton, owned the Tavern.[6] After the store Patrick owned went bankrupt, he and his family moved to the Tavern, where he both lived and worked. Between bartending and playing the fiddle for the patrons, he debated with lawyers and dispensed legal advice despite his lack of professional training. Gaining some notoriety for his articulateness and learning a little about the legal profession through this experience, Henry went to Williamsburg in 1760 to obtain his license to practice law.[7]

Hanover Tavern has been rebuilt, expanded, and renovated multiple times since Patrick Henry lived there. Today it boasts a dinner theater and restaurant, as well as hosts special events such as field trips and weddings.

Scotchtown

In 1767, a few years after becoming a successful lawyer due to the Parson’s Cause case, Patrick Henry bought Scotchtown to house his growing family. While living in this house, Henry served at the First Continental Congress, was elected Virginia’s commander in chief and first governor, helped write Virginia’s state constitution, and supported the Continental Army and Revolutionary war effort. It was also at this house that his first wife, Sarah Shelton, died of depression. Patrick Henry sold Scotchtown in 1777.

Today the original house is owned by Preservation Virginia and has been restored to how it looked during Henry’s life there. The grounds and outbuildings have been recreated, and are available year round for public tours.

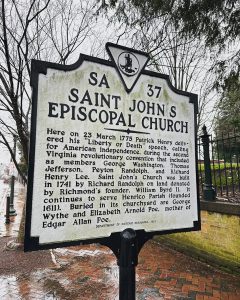

Historic St. John’s Church

In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, dissolved the House of Burgesses due to their revolutionary leanings. In disregard of the governor’s declaration, the counties of Virginia called a convention to be held in Richmond. The Second Virginia Convention delegates chose Richmond because it was not safe for them to meet in Williamsburg, the then-capital of Virginia. As the largest building in town, the Henrico Parish Church was selected to house the convention.[8] Patrick Henry was among the 120 delegates that attended.

In 1775, Lord Dunmore, the royal governor of Virginia, dissolved the House of Burgesses due to their revolutionary leanings. In disregard of the governor’s declaration, the counties of Virginia called a convention to be held in Richmond. The Second Virginia Convention delegates chose Richmond because it was not safe for them to meet in Williamsburg, the then-capital of Virginia. As the largest building in town, the Henrico Parish Church was selected to house the convention.[8] Patrick Henry was among the 120 delegates that attended.

On March 23, 1775 he introduced three resolutions relating to the colonial militia. Due to Lord Dunmore’s interference with colonial legislature, the laws sustaining the militia had lapsed. Henry’s first and second resolutions detailed the necessity of a well-regulated militia as “the natural Strength and only Security of a free Government” and called for the militia to be stood up “for the protection and Defence of the Country.”[9] His third resolution called for Virginia to be put into a state of defense, and “to prepare a Plan for embodying, arming, and disciplining such a Number of Men as may be sufficient for that purpose.”[10]

Standing at the front of the Henrico Parish Church, Patrick Henry vigorously garnered support for his resolutions with the famous line “Give me Liberty, or give me Death!” The convention passed his resolutions, and Henry left to lead the militia to Williamsburg.

Today the church—renamed the St. John’s Episcopal Church in 1833—is much larger than it was during Henry’s resounding speech. Yet the original wooden walls that heard his moving words still stand, and the sounding board above the pulpit resonated his famous speech. The church houses its congregation on Sundays but holds tours and reenactments of the Second Virginia Convention throughout the year.

Red Hill

The Henrys moved to Red Hill in 1796, where both Patrick and his second wife Dorothea were eventually buried. Red Hill brought in 20,000 pounds per year of tobacco on its 3,000 acres.[11] As a working plantation, the house was modest with numerous outbuildings including a kitchen, coachman’s cabin, blacksmith shop, and smokehouse. After retiring from public service, Henry resumed practicing law.[12] To facilitate this, he built a law office at Red Hill, which also served as a schoolroom and bedroom for his children and grandchildren.

Patrick Henry loved nature all his life, and the gardens at Red Hill reflect this affection. He often enjoyed walking under trees, and in front of the house is a massive Osage Orange tree. The tree is estimated to be over 370 years old, and Patrick Henry enjoyed its shade.

After his death, Red Hill passed through the Henry family and the house was expanded with successive generations. Today the house has been restored to the size it was during Patrick Henry’s lifetime. Not far from the house is the family graveyard, where Patrick and Dorothea are buried side by side.

Throughout his life, both as a lawyer and as a militia commander, Patrick Henry fought to defend the rights of the people and to motivate them to action. While Patrick Henry is rightfully renowned for his passionate speeches, the sites where he lived and worked across Hanover County provide rich details about his life beyond his famous quote.

[1]Historic Polegreen Church Foundation, “The Polegreen Story,” historicpolegreenchurch.org/story.php.

[2]George H. Bost, “Samuel Davies: The South’s Great Awakener,” Journal of The Presbyterian Historical Society, Vol. 33, No. 3 (September 1955), 135-136.

[3]George William Pilcher, “Samuel Davies and Religious Toleration in Virginia,” The Historian, Vol. 28, No. 1 (1965), 48-71.

[4]Robert F. Scott, “Colonial Presbyterianism in the Valley of Virginia 1727-1775,” Journal of the Presbyterian Historical Society, Vol. 35, No. 2 (Jun 1957), 88.

[5]Bost, “Samuel Davies: The South’s Great Awakener,” 152.

[6]Hanover Tavern, “Tavern History,” hanovertavern.org/history/tavern-history/.

[7]Harlow Giles Unger, Lion of Liberty: Patrick Henry and the Call to a New Nation (Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2010), 15-17.

[8]Historic St. John’s Church, “The Second Virginia Convention,” www.historicstjohnschurch.org/2nd-virginia-convention.

[9]Unger, Lion of Liberty, 95.

[12]Red Hill: Patrick Henry National Memorial, “History of Red Hil,” www.redhill.org/red-hill/.

4 Comments

I highly recommend having a meal at the Historic Hanover Tavern.. The food is beyond delicious and the service is always phenomenal!

Very good article, thanks for publishing it! One correction. Lord Dunmore dissolved the House of Burgesses in May 1774, not in 1775.

Everyone should make a point to visit St. John’s Church (and attend their Liberty or Death reenactment), Red Hill, and the other sites listed in the article.

There’s a number of factual mistakes in this article, including when he bought and sold Scotch Town; when his store closed; his having built a law office at Red Hill; his leading the Hanover militia to Williamsburg directly after his “liberty or Death!” Speech; and claiming Shelton’s Tavern is the origins of the tavern standing near the courthouse today, but overall it’s a nice article.

I see you failed to include that he had a large plantation in what is now Henry County. He lived there between his time in Scotchtown and Red Hill. Henry County was later divided into Patrick and Henry counties.