Amphibious operations, which involve landing troops and supplies from the sea to the land, are extremely difficult and require special techniques, close coordination between the navy and army, as well as specialized equipment. The British learned the required skills during the Seven Years’ War. After a failed attack on the French port of Rochefort the British revised their amphibious command and control procedures, and designed purpose-built launches, known familiarly as flatboats, especially for landing on enemy beaches.[1]

Ideally, the troops would be taken as close to the shore as possible so they would have the shortest distance possible to wade ashore and be exposed to enemy fire. Standard longboats were unsuitable for landing operations due to their deep draft which could be up to five feet when loaded.[2] Also, the long and narrow design of a longboat made loading and unloading troops difficult as they would have to get past the oarsmen and the oars to exit over the sides.

In April 1758 the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty approved the design for a shallow draft flatboat.[3] Two sizes were planned. One was thirty-six-feet long and ten-feet two-inches broad. It would carry about fifty men plus a naval officer, gunner and twenty oarsmen. A smaller version was thirty-feet long, nine-feet nine-inches broad and carry sixteen oarsmen. Both of these boats were only two-feet eleven-inches in depth with wide, rounded bows and transom sterns. Fully loaded they required only two-feet of water, which allowed them to get close to the beach.[4]

The British flatboats used in the American Revolution were, with minor variations, the same. Their capacity was about 10,000 to 12,000 pounds not including the oarsmen. Troops were packed in close together seated in two rows facing each other with their muskets standing upright between their knees. A sailor manned the tiller while twenty others sat outboard of the troops to man the oars. The flatboats could also be fitted with a mast, sails and a small cannon, or swivel gun mounted in the bow.[5] The swivel gun added a slight bit of defensive firepower. However procedure dictated that the landing site would be heavily bombarded by warships prior to the landing. The flatboats were not meant to fight their way ashore.

Twin gangplanks were extended over the bow onto the beach allowing for fast and orderly entry and exit of the troops. The procedure was described by a witness:

“All these flat boats…were lying in one row along the shore, and as soon as the regiment had marched past, it formed up again close to the shore, and awaited the signal for entering the boats. Immediately on this being given each officer marched with his men to the boats,…then he and his drummer entered first and passed right through from the bows on shore to the stern, the whole division following him without breaking their ranks; so that in two minutes everybody was in the boat.”[6]

On reaching the enemy shore the men would march out over the bow onto the beach and would be combat ready immediately. Just prior to hitting the beach the flatboat would drop a kedge anchor off the stern. When the troops had disembarked the anchor was pulled, oars backed, and the flatboat would head out to sea for another load.

One variation of the flatboat was constructed and used in Canada. Major General Phillips’ brigade orders of June 3, 1776 state:

“Lieut. [William] Twiss is to proceed to Three Rivers and give his directions for construction of Boats. The description of one of these Boats is, a Common flat Bottom called a King’s Boat or Royal Boat calculated to carry from 30 to 40 men with stores and provisions, with this only difference, that the Bow of each Boat is to be made square resembling an English Punt for the conveniency of disembarking the Troops by the means of a kind of broad gang board with Loop-holes made in it for Musquetry, and which may serve as a Mantlet[7] when advancing towards an Enemy, and must be made strong accordingly.”[8]

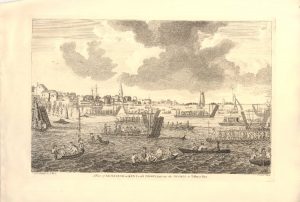

Documentation of such a gang board or ramp used elsewhere in the American Revolution has not been found. An image of flatboats with a similar “gang board” appears in a 1780 image “A View of Gravesend in Kent, with Troops passing the Thames to Tilbury Fort.”[9] Such a gang board or ramp strong enough to provide protection from enemy fire would have been very heavy and may have caused stability problems for the flatboat. The infantry, being packed in tightly, would not have been able to use the gang board as a mantlet or fire through the loopholes.

Another modification to the flatboats allowed them to be used to carry artillery. Planks installed the length of the boat and gangplanks placed over the bows allowed the artillery to be wheeled on and off the flatboat.[10] The Robert Cleveley image of the landing at Kip’s Bay clearly shows flatboats carrying artillery and others carrying infantry.[11]

The effectiveness of the flatboats was clearly demonstrated on the morning of August 22, 1776 in a spectacular display of organizational prowess and seamanship when the Royal Navy shifted the bulk of the British army from Staten Island to Gravesend Bay on Long Island. At 4 AM flatboats were at the beach at Staten Island to pick up the first wave of troops.

The landing itself was covered by three frigates and two bomb-ketches which bombarded the beach prior to the landing. The landing however was unopposed. The Captain of H.M.S. Eagle, Henry Duncan who was involved in the landing, records that:

The flat boats were all assembled by four o’clock [AM] on the beach, under the particular command of Commodore Hotham…About eight the Phoenix fired a gun and hoisted a striped flag, blue and white, at the mizen top-mast head, as a signal for the troops to proceed to the shore. A little after eight all the ships with troops for the first landing were in motion; and the boats that had taken in about 1,000 troops from Staten Island began to move across towards Gravesend Bay, in Long Island. Half-past eight Commodore Hotham hoisted the red flag in his boat as a signal for the boats to push on shore. The boats immediately obeyed the signal, and in ten minutes or thereabout 4,000 men were on the beach, formed and moved forward. The wind blew down the harbour, but the flood tide had made up too strong for the ships to get down in their intended station; nevertheless, by twelve o’clock or very soon after, all the troops were on shore, to the number of 15,000, and by three o’clock we had an account of the army being got as far as Flat Bush, six or seven miles from where they landed.[12]

This landing involved seventy five flatboats each carrying fifty infantrymen, plus eleven bateaux (long, shallow draft boat with pointed bow and stern). The first embarkation of 4,000 men consisted of the light infantry and the reserve. It is very significant that not only did these troops reach the beach quickly but that after their arrival they were immediately able to move out in an orderly fashion to secure the beach. The evening before the amphibious landing on Long Island the troops to be landed in the second and third waves were put on board transports. The second embarkation, from the transports, of five thousand men was delivered to the beach by the flatboats so quickly after the first landing that they could have supported the light infantry should there have been opposition. While the flatboats made their way to the beach with this second wave of troops the now empty transports moved out and were replaced by transports containing more troops to be taken to the beach in their turn. Three hours after the first landing 15,000 troops were ashore along with their baggage, equipment and forty pieces of artillery.[13] Moving a combat force of this size so quickly had never before been seen on this continent.

Less than a month later, on September 15, the flatboats were again used with great success. Unlike the landing at Gravesend Bay the crossing of the East River from Long Island to Manhattan Island required an assault on a hostile shore.

During the night of the 14th the British anchored five warships with their broadsides facing the American position on shore, only three yards away.[14] The Americans had dug trenches in anticipation of a landing. However they were not prepared for the power of the Royal Navy’s assault.

An American, Joseph Plumb Martin was on the receiving end of the attack. He described seeing “…their boats coming out of a creek or cover on Long Island side of the water, filled with British soldiers. When they came to the edge of the tide, they formed their boats in line. They continued to augment their forces from the island until they appeared like a large clover field in full bloom.”[15] A British officer, Captain William Evelyn of the Light Infantry, recalled that “the water covered with boats full of armed men pressing eagerly toward the shore, was certainly one of the grandest and most sublime scenes ever exhibited.”[16]

Francis, Lord Rawdon was in one of the eighty four flatboats making up the landing force. As he “approached [we] saw the breastworks filled with men, and two or three large columns marching down in great parade to support them. The Hessians, who were not used to this water business and who conceived that it must be exceedingly uncomfortable to be shot at whilst they were quite defenceless and jammed so close together, began to sing hymns immediately. Our men expressed their feelings as strongly, though in a different manner, by damning themselves and the enemy indiscriminately with wonderful fervency.”[17]

When the flatboats were within fifty yards of the ships the signal was given and the warships let loose their first volley upon the breastworks. To Martin “there came such a peal of thunder from the British shipping that I thought my head would go with the sound.” Bartholomew James aboard HMS Orpheus wrote that “it is hardly possible to conceive what a tremendous fire was kept up by those five ships for fifty-nine minutes, in which time we fired away, in the Orpheus alone, five thousand three hundred and seventy six pounds of powder. The first broadside made a considerable breach in their works, and the enemy fled on all sides, confused and calling for quarter…..” To Lord Rawdon it was “the most tremendous peal I ever heard. The breastworks were blown to pieces in a few minutes, and those who were to have defended it were happy to escape as quick as possible…..We pressed to shore, landed, and formed without losing a single man…” HMS Carysfort “fired 20 broadsides in the Space of an hour, with Double headed round & Grape Shott.” [18]

American Captain Samuel Richards saw “a dense column of the enemy moving down to the waters edge and embarking on board flat boats. Knowing their object we prepared to receive them. As soon as they began their approach the ships opened a tremendous fire upon us. The column of boats on leaving the shore proceeded directly towards us; when arriving about half way across the sound [East River] they turned their course and proceeded to Kip’s bay – about three quarters of a mile above us – where they landed; their landing there being unexpected they met with no opposition: the firing from the ships being continued – our slight embankment being hastily thrown up – was fast tumbling away by the enemy’s shott. Our troops left their post in disorder…”[19]

The landing at Kip’s Bay was entirely successful. The astonishing firepower of the warships combined with the efficient landing of numerous troops was far more than the Americans could withstand. This was shock and awe.

Such is the power of a well orchestrated amphibious landing. Without flat-bottomed landing craft the Royal Navy and the British Army would not have been capable of taking advantage of the enormous coastline of the United States. While the humble flatboats did not win the war for the British the boats did allow a strategy of mobility which was hoped would overcome the Americans whose movements were limited by the feet of the foot soldier.

[1] Robert Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain, from 1727-1783 (London: Longman, 1804), 2:167.

[2] Hugh Boscawen, “The Origins of the Flat-Bottomed Landing Craft 1757-1758,” Army Museum ’84 (Journal of the National Army Museum, Royal Hospital Road, London, UK, 1985), 24.

[3] Contemporary scale models, complete with Army and Navy figures, can be found at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England.

[4] Boscawen, Origins, 25.

[5] National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, England.

[6] Boscawen, Origins, 28. The quotation is from Count F. Kielmansegge, Diary of a Journey to England in the Years 1761-1762 (London: 1902), 258-259. A division, in this context, is a company or half-company, about 50 men.

[7] Mantlet, a portable defensive shield.

[8] James Murray Hadden, Hadden’s Journal and Orderly Books (Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1884), 169.

[9] “A view of Gravesend in Kent, with Troops passing the Thames to Tilbury Fort, 1780,” British Museum, http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=904082&objectId=3312410&partId=1

[10] Adrian B. Caruana, Grasshoppers and Butterflies: The Light 3-Pounders of Pattison and Townshend (Bloomfield, Ontario: Museum Restoration Service, 1980), 30.

[11] Don N. Hagist, “A New Interpretation of a Robert Cleveley Watercolour,” Mariner’s Mirror, 94:3, 2008, 326-30.

[12] Henry Duncan, “Journals of Henry Duncan,” in John Knox Laughton, Naval Miscellany (London: Navy Records Society, 1902), 122-123.

[13] Beatson, Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain from 1727-1783, (London: Longman, 1804), 4:156-157.

[14] Journals of HMS Phoenix, HMS Roebuck, HMS Orpheus, HMS Rose, HMS Carysfort in William James Morgan, ed. Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington: Department of the Navy, 1972), 6:838-840.

[15] Joseph Plumb Martin, George F. Scheer, ed., Private Yankee Doodle (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1962), 33-34.

[16] Henry P. Johnston, Battle of Harlem Heights (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1897), 34.

[17] William P. Cumming and Hugh Rankin, The Fate of a Nation, The American Revolution Through Contemporary Eyes (London: Phaidon Press, 1975), 110-111.

[18] Journal of Bartholomew James and journal of HMS Carysfort, in Morgan, Naval Documents, 6:841, 849. Martin, Private Yankee Doodle, 34. Cumming, Fate of a Nation, 111.

[19] Morgan, Naval Documents, 6:844-845.

28 Comments

Great article Hugh ~ Can you shed any light on if, and how, Washington and the 14th Massachusetts Continentals learned anything from British amphibious operations for their operations night crossings of 29 Aug. and 25 Dec. 1776?

The British amphibious landings were well choreographed and minutely detailed operations. There were strict orders pertaining to positioning, timing as well as signalling procedures. I do not believe that any of this carried over to any Continental operation.

Very interesting aspect of the British invasion of NY. I submit that had Howe used the flatboats earller than when he did he might have been able to surprise the rebels along the Bronx, Pelham and New Rochelle shorelines, all of which had low-lying beaches. In doing so, he might have been more successful in cutting off the American army’s retreat to White Plains. Great illustrations too.

I agree with you. Howe has much to answer for regarding his slowness.

“The British amphibious landings were well choreographed and minutely detailed operations.”

“Howe has much to answer for regarding his slowness.”

Perhaps the first statement is the answer to the second? Howe is much maligned for “slowness” by people who have no experience managing armies. It’s easy to say that a victory one day should have been followed up by a persuit the next day, but how clear was it to the commander exactly where all of his troops were, and what condition they were in, the morning after that great victory? When the results of a great battle change the tactical situation, it takes some time to assess that situation and determine what to do next, and how to do it. Did Howe do worse than other generals of his era, in terms of conducting offensive operations? It’s easy to say, after the fact, what could have happened if he had acted more quickly, but that doesn’t mean it was feasible to have acted more quickly.

Hugh – throughout your very interesting and enlightening article, I kept seeing the comparisons of British flatboats to American LCVPs (or “Higgins boats”) of WWII. Except that the British had the idea at least 170 years before!

The major variations being that British troops sat rather than standing as American GIs did, and Higgins boats had a metal bow ramp that came down in front. Otherwise the two transport vessels were both wooden, had some sort of self-defense weapon (cannon vs. .50 caliber machine gun), and were excellent beach-landing, ship-to-shore vessels that circumvented the need for a disembarkation harbor. Very intriguing and well researched, Hugh. Thank you.

John, you read my mind. I initially considered writing a comparison of the two flatboat/landing craft designs. I even made the trek to New Orleans to see the replica in the (wonderful) WWII Museum. The 18th century version carried a greater load of men/supplies, was silent and in a short sprint was probably just as fast as the Higgins Boat’s 9 knots. They both could operate in extremely shallow water.

Hugh and John,

There is also a resemblance to the flat-bottomed boats (gondolas) that Arnold had built and used on Lake Champlain at Valcour Island. I have no idea what the reasoning was for this style of boat was (for shallows, to carry bulky goods? – maybe Mike Barbieri can weigh in on this) in the interior waterways, but is there some common denominator?

The gundalow did have a flat bottom but was longer than a troop transport flatboat. It also was made for fighting – being supplied with cannon and swivels. It did not have the many oarsmen for propulsion that a troop transport had. I too would like to hear from Mike Barbieri on this subject.

First off, Hugh, thanks for writing up a really interesting and informative article on something most people wouldn’t think about.

I do have some comments (pardon the randomness) regarding the differences and similarities between the Brit landing craft and Arnold’s gondolas. As Gary said, they both could get into shallow waters and, as Hugh mentioned, they are different in that the Brit creations had the job of carrying troops and goods while Arnold built his for fighting. There is a bit more to the story, however. In both cases, being flat-bottomed they are simple to build which served as a major factor in Arnold’s decision–he needed as many craft as possible and he needed them immediately. He also just took the design of a double-ended bateau and made it considerably larger and stronger. They carried three large cannon and upwards of eight swivels. Arnold’s gondolas also had high sides while the Brit craft featured lower ones. While the Brit craft could be fitted with sails, they generally rowed them around. In contrast, every one of Arnold’s gondolas (and the ones used elsewhere by the Americans) had a single mast with two square sails but also had upwards of fourteen or sixteen rowing stations. For more details on the gondolas, visit http://www.lcmm.org/our_fleet/philadelphia.htm and http://www.historiclakes.org/Valcour/philly.htm.

I would like to note that there seem to have been two types of Brit landing craft. They had just a plain ordinary barge built not unlike a big box with low sides and no top. However, they also had the type of craft shown in the painting at the top of the article and in the picture of the model included in the article. While called “flat-bottomed,” they are not dead flat like the barges or bateaux or Arnold gondolas. Rather, the bottoms do have some curve to them and something of a keel which made them much easier to control than the dead flat keelless bottom of the barges and Arnold’s gondolas.

The Brits had over twenty of the latter type in varying lengths on Lake Champlain and at the battle of Valcour Island. Rather than use as troop transports (they used bateaux for that), they mounted artillery in them–a couple had 24-pounders in them and half-a-dozen had howitzers. Over a dozen of these boats had been built in England as kits. They transported the pieces to North America and assembled them at St. John’s on the Richelieu River. Somewhere around here, I have a drawing of a transport built to carry landing craft but I can’t find it now. It looks like they cut a ship in half and spliced in a long section.

Thoughts from an inland mariner: I like salt on my meat, not in my water.

Mike, thanks very much for this added information and clarification. Your expertise really shines. Much appreciated.

Thanks for a fascinating piece Hugh. The flatboats were of such a notable design that Washington’s intelligence operatives often kept an eye for their presence. In the spring and summer of 1779 at least, members of the Culper Ring informed Gen. Washington about British construction of flatboats on Manhattan as a possible indication of British preparations for amphibious landings in the expected summer campaign. They were right – that summer British commanders used the flatboats to rapidly and effectively land troops in a series of raids at Portsmouth, Virginia and along the Connecticut coast.

Thanks Mike. I wasn’t aware of that. Makes sense but I hadn’t thought of it.

How did they get the flatboats to the landing sight? Were they manufactured locally or brought over by special transports like our LSTs and other landing ships?

Many flatboats were built locally. Others were transported from England. Clearly, they were troublesome – a frigate could carry only one. Special transports were contracted to haul the flatboats – the flatboats could be “nested” within each other to some extent which helped on the flatboat transport vessels. Special booms were required to lift them from/to the water. That operation was made more difficult due to the masts and gear above deck. I have not seen a good description of just how the flatboats were handled on a flatboat transport.

Hugh, this is very interesting, thanks. Have you come across first hand accounts of the British landing in June 1776 north of Charleston on “Long Island” prior to the attack on Fort Moultrie, South Carolina? Would those landings have mirrored the techniques you describe above? Any information appreciated.

It is my understanding that the same flatboats used at Long Island (outside of Charleston Harbor, SC) were also used in NY (plus others transported and constructed in NY). Several years ago I was deeply involved in the landing on Long Island and the action at Breech Inlet….however, I don’t recall that there was a bombardment prior to the landing as the island was undefended.

The British also used flatboats brilliantly in their 1777 invasion of Stony Point. There was some pre-invasion bombardment but the British also feinted toward the east bank of the Hudson where they not only fooled Putnam into believing a landing was imminent but also freezing him in place as to sending reinforcements across the river to Forts Clinton and Montgomery. The west bank landing at Stony Point was under the cover of a heavy morning fog.

The “Flatt-bottomed boat” for the AWI was a redesign of the French & Indian War era flatboat. I believe Colonel Hugh Boscawen erred in assigning the 30 foot model to the AWI. The original 30 foot model, designed to carry 40 soldiers and 16 “Seamen Oars,” was approved 16 July 1775 by Sir John Williams, Surveyor of the Navy, had a transom and was 30’ 0” length, 9’ 9” breath, 2’ 11” depth, admeasured 10.15 tons and was rowed by 12’ 8” long oars. On 01 Aug 1775 Admiralty directed the Navy Board to procure 20 boats, 17 to be built in merchant yards and 3 in the King’s Yards, all to be completed within a month. On 18 Oct 1775 a revised design was approved, the revision apparently based on sea trials faulting the design as having a broad and full transom which caused them to be unhandy in heavy surf. The revised design merely eliminated the transom and faired stern into the rudder post by lengthening the boats one foot to 31’ 0” length (and admeasured 12 tons 2 cwt). As of 18 Oct 1775 only 10 of the contracted flat boats had been delivered and Admiralty ordered the undelivered 10 boats to be built to the revised design.

I do not know how many Flatt-bottomed Boats” were built during the AWI but at least 20 also were sent to support the relief forces sent to Canada in 1776. During the 22 Aug 1776 landing in Gravesend Bay, Long Island, the landing was divided into ten divisions but the exact count of flatboats is not given as Lord Howe reported to Admiralty: “The Flat Boats Gallies and Batteaux manned from the Ships of War commanded respectfully by the Captains Vandeput, Mason, Curtis, Caldwell, Phipps, Caulfield, Uppleby and Duncan. The rest of the Batteaux making a tenth Division, manned from the Transports, were under the conduct of Lieutenant Bristow, an Assistant Agent.” Apparently there were eight flatboats per division as the log of HMS Preston (Capt. Samuel Uppleby) reported “received & Manned 8 flat boats, together with our own Boats and sent them to Land Troops on Long Island” and the log of HMS Senegal (Captain Roger Curtis) reported “At 2 A M the Flat boats No 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30 with the Capt & Lieut to the Narrows of Staten Island to Imbark the Troops”; however, the log of HMS Asia (Captain George Vandeout) reports only “A M at 6 sent 6 Flat boats & one Batteau”. The two landing waves were reported as landing 4,000 men in the first wave and ‘about’ 5,000 men in the second wave, numbers which seem to exceed the capacity of the landing craft.

Between Sept 1776 & March 1777, the New York Navy Yard reported: “Repaired and Altered Eighty five Flat Boats, & Seventeen Batteaux many of which were in very bad Condition, having been stove and otherwise much damaged by the frequent embarkations and Landings of the Troops &c.”

In Dec 1777 the Navy Board minutes show ordering 10 Flat bottomed Boats at £1.14.0d per foot [£52.7.0d each] with three contractors to deliver 2 each in one month and four contractors to deliver one each within 3 weeks.

One untold story of the AWI is the difficulty of maneuvering of the Flat-bottomed Boats when crossing the Hudson and East rivers when tide, current and wind is against progress plus low freeboard when loaded. This would be a good project for a student of naval architecture.

N.B. Copies of the copyright draughts of the Flatt-bottomed Boats mentioned above can be purchased from The National Maritime Museum in Greenwich; i.e., drawing # ZAZ5284 (repo ID # J0102) and ZAZ5285 (repo ID # J0103). The collection also includes both earlier and later designs and a 1783 mounting plan for a 12-pounder Carronade.

Bob Brooks – Thank you very much for this information. I find it fascinating.

Great information Bob Brooks. As a docent at Washington Crossing State Park (PA), we explain the finer points of the Durham boats that were used on 25 Dec ’76. Your learned information is excellent for comparison. Does anyone know what type boats, and how many, were used by the Continentals on 29 Aug ’76 to escape from Brooklyn?

Bob Brooks comment about the modified stern on the later 1775 flatboat design drew me back to the Robert Cleveley image at the top of this article. Of the 6 flatboats closest to the viewer it appears that the two on the right may have the modified stern. The four on the left appear to have the flat transom of the earlier design. I am fascinated.

The information presented in the article and comments suggests that ships’ boats were used in addition to flat-bottomed boats for landings. I wonder if all of the boats shown in the Cleveley painting are flat-bottomed boats, or if it’s a mix of those and more conventional ships’ boats?

Great article, Hugh. I recall reading, but do not recall where, that Royal Navy flatboats could be collapsed (or folded up?) for more efficient storage on board British ships.

Christian – I have seen on the National Maritime Museum website where they state that the flatboats could be partially disassembled and then nested one inside the other. However, I have not seen any primary source that confirms that was the case. These were bulky and difficult to transport. A frigate for example could take only one – and it must have been a real pain in the next and have an impact on its sailing and fighting capabilities. They were shipped long distances on transports but I do not know just how they were stored aboard the transports. More research needs to be done.

Don – I think a thorough study of high resolution period images of flatboats – and other craft used in landing ops – is needed.

The following applies to the boats used by the British in the 1776 campaign on Lake Champlain. On November 9, 1776, Major General William Phillips (commander of the Royal Artillery detachment) wrote to Lord George Germain:

“It appears to me an object very worthy your Excellency’s consideration for the next campaign, I take the liberty of submitting to you, Sir, whether it would not be proper to make a demand from England for a certain number of these Boats, calculated to mount guns upon, to be sent from thence framed, so as to be put together in Canada. …

“The boats upon this principle which came from England this year must have been constructed by different persons; they were almost all different one from the other; some were indeed very good, others but indifferent, and two so very bad that they could not with the utmost endeavor be put together here. …

“I beg further to suggest that it be recommended that if the Navy construct these boats it may be done at one Dock Yard: or, if by Contract, by one Person, as by this means the Timbers will be all conformable to the plan, & there will be no difficulty in putting the boats together when they arrive in Canada.”

Caught my attention with the sentence about Rochefort–a new piece of information about l’Hermione’s home port!

Very interesting and well-written article! Thanks, Hugh.

Kim

The British and Hessian troops crossed to/from Staten Island and New Jersey in June 1780. References to a boat bridge of Sloops (20 in one reference) is made in documents and on maps. Could it have been flatboats. Lt George Mathew made an observation that 5-6 men abreast could march across was possible. I’m trying picture how they were able to transport 5000-6000 troops, horses, cannon, etc across a boat bridge.