As recounted in a previous article, in October 1774 a sailor named Samuel Dyer returned to Boston, accusing high officers of the British army of holding him captive, interrogating him about the Boston Tea Party, and shipping him off to London in irons. Unable to file a lawsuit for damages, Dyer attacked two army officers on the town’s main street, cutting one and nearly shooting another—the first gunshot aimed at royal authorities in Boston in the whole Revolution. Those actions alarmed both sides of the political divide, and Dyer was soon locked up in the Boston jail. Everyone seemed to agree the man was insane.

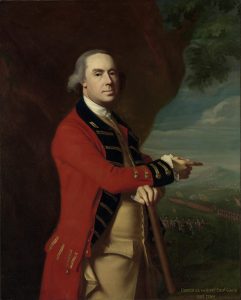

That attempted homicide undoubtedly alarmed Thomas Gage, the British army general appointed to be royal governor of Massachusetts. Not just because the targets had been two of his top officers, artillery commander Lt. Col. Samuel Cleaveland and chief engineer Capt. John Montresor. Not just because the attacker had received support from top Whigs in London, Newport, and Boston. Gage had to deal with the uncomfortable knowledge that many of the Samuel Dyer’s outrageous accusations were basically true. Just because Dyer might have been crazy didn’t mean that royal authorities hadn’t been out to get him.

The sailor’s first complaint was that the army had taken him prisoner. In Governor Gage’s files is the attorney Robert Auchmuty’s bill listing work on July 5 for a case labeled “King vs Dyer.” Among those tasks were:

To draft of an Information against Samuel Dyer for seducing James Little & Andrew Hughes private Soldiers in his Majestys 4th Regiment to desert

To Special Warrant to apprehend Dyer & attendance in Camp who was discharg

To attend 3 different Times at ye Province House upon ye same Affair.

To Hearing ye Complaint & three Conferences with Col Maddison upon a point of Law as to ye legality of Dyer Committment in Camp.[1]

In preparing that bill, Auchmuty clarified at the bottom that he had “Received nothing” so far.

Seducing soldiers to desert was a serious crime, but it would have been legally difficult and politically dangerous to prosecute Dyer on that charge in Boston. According to Gage, “Lieutenant Colonel [George] Maddison prevailed with Admiral [John] Montagu, to impress and carry [Dyer] to England.”[2] Since Dyer was a sailor, he was subject to a long British tradition, hotly disputed, of naval officers drafting or “impressing” seamen for their ships. In his log entry for on July 7, the captain of HMS Captain wrote: “at 5 came on board General Gage Saluted him with 13 Guns as we did at his leaving the Ship.”[3] The next day, the Captain weighed anchor, carrying both Montagu and Dyer. When he heard about the sailor’s assault on the two officers, Gage’s adjutant, Maj. Stephen Kemble, immediately recognized him as the “Man who had been carried from Boston by Admiral Montague to England for Inveigling the Soldiers from their Colours.”[4]

Furthermore, Dyer was correct in claiming he had been interrogated by British officials, though not men with such high positions in the government. At the same time, the sailor was lying about how he had resisted all those attempts to make him share incriminating information about the Boston Whigs. On July 30, as the Captain neared Europe, Admiral Montagu extracted a deposition from him. It said “Samuel Dyer (Seaman now on board His Majs. Ship Captain)” made the following statements under oath:[5]

•“he has been frequently employed by the said Mr. Samuel Adams & Doctr. [Thomas] Young to go to the Northend of the Town of Boston, to collect Shipwrights & Carpenters &c. together, to certain Public Houses (the Expence of which usedto be paid by People who stiled themselves of Liberty, of which the said Adams and Young, generally, were the Heads of the Party) in order that they might be sure of a Number of Men, upon making a Signal, at a Minutes warning, whenever they wished to collect a Mob”.

•“some time in June last . . . he received a Letter from Mr. Samuel Adams of Boston, desiring him to come to Town, and meet him at the House of Doctr. Young” to deal with “a Quantity of a Tea being shiped by the East India Company on board Merchants Ships for the Port of Boston”. That “Tea was afterwards destroyed by a Number of People in disguise,” with the “Captains of the Gang” being “Mr. [blank] Short a Merchant near the Mill Bridge in Boston & Capt. Wood or Hood who commands a Merchant Vessel in Mr. John Hancock’s employ.” Dyer himself had not been at the Tea Party, however, being “prevented by Sickness.”

•“Mr. Samuel Adams did promise him at the House of Doctr. Young in June last,” that Dyer would receive £4 sterling for every soldier he could convince to desert, and “every Soldier should receive the like Sum of four pounds, or three hundred Acres of Land, and a Quantity of Provisions so soon as they arrived at a certain part of the Country, provided they would cultivate the said Land.”

•Clothing to disguise those deserters was “lodged at proper Places,” and “a Boat should always be ready at Hancock’s Wharf” to carry them out of town by water. What’s more, “Captain Conner, Inn Holder near the Mill Bridge in Boston,” had promised horses “to carry the Soldiers off” and “a Room or Store . . . to conceal them in.” And the key to that room was in Dyer’s possession.

Dyer signed that document with a mark—his initials.

On the same day Admiral Montagu questioned another sailor, Samuel Mouat. He too accused “Mr. John Short Merchant near the Draw Bridge in Boston” of bribing a soldier to desert. Mouat also claimed that Judge Meshach Weare of New Hampshire had offered “393 Acres of Land to any Soldier who would desert.” Reportedly, Weare even offered one former soldier confined in the Amherst, New Hampshire, jail for debt “his Fredom and £150 Stg. if he would Head a Regiment of Arm’d Men to attack the Kings Troops at Boston.” Other conspirators, Mouat said, were “Mr. Page and Mr. Joseph Buckman Farmers in upper Cohorse” and a New Hampshire magistrate helpfully named “John Smith Esqr.” Mouat also signed his deposition with a mark.[6]

When Dyer arrived back in America in Newport, Rhode Island, he had told local Patriots that on the high seas Admiral Montagu had “often threatened” him and “offered him Rewards at Times to accuse Mr. Hankock and other eminent Patriots, [. . . but] Dyre said he knew nothing of the matter.”[7] In fact, Dyer had put his initials on a document accusing Hancock, Adams, and other Bostonians of planning the destruction of the East India Company tea even before it was shipped to Boston. That deposition had described Dr. Thomas Young as trying to entice British soldiers to desert, a fact that Dyer neglected to disclose when he met Doctor Young again in Rhode Island. The sailor concealed from the New England Patriots how much he had cooperated with Montagu’s inquiry. He might have been under duress aboard the Captain, but it appears likely that even back in Boston Dyer had dropped hints of knowing things about the Tea Party that royal officials were anxious to hear.

At the same time, most of the testimony Dyer offered to the admiral was nonsense. As one of the “Captains of the Gang” in destroying the tea he named John Hood, a captain working for Hancock. Newspaper records show that Hood was at sea on the date of the Tea Party.[8] Dyer said “Captain Conner, Inn Holder near the Mill Bridge in Boston,” would provide horses for deserters seeking to sneak out of town. Charles Conner did own a boarding-house and stable near the North End; during the Tea Party he had made himself notorious by trying to make off with some tea for himself, so he was an easy scapegoat.[9] However, putting a deserting soldier on a horse in the middle of town would only have made that man more conspicuous, so that escape method made no sense. Notably, Dyer was careful not to confess to any crimes himself: he had been ill during the Tea Party, he said, and he never claimed to have succeeded in bringing off a deserter.

The next day, as the Captain was “Running up Channell,” Dyer prepared a different document.[10] In a personal letter to Lord Dartmouth, the secretary of state, written “From On Board His Majestys Ship Captain at Spithead,”[11] Dyer offered to spill many Patriot secrets in exchange for protection:

Whearas I am Brought Prisoner from Boston In New England, I humbly beg your Lordships to Take my Case into Consideration, whereas I shall be Examined before your Lordships, I will Declare the truth, that shall be required of me, in all Questions, and shall keep nothing Secerit from your Lordships, Whereas I have been Lead away by Gentlemen of Boston, being so unwise, as to take there Counsell, Whareas I have Ruined myself, and Wife and Children, Unless your Lordships will take my Case in hand, and settle me in som Part in England, as I shall never Dare to return to Boston, I must humbly beg your Lordships Clemency; I must humbly Intreat your Lordships to hear me Examined, and I shall relate all affairs from the begining, to the Ending in the town of Boston, and Province, I most humbly Intreat your Lordships to here me Examined me as soone as Possibly, as there is Boston, and Charlestown People, here belonging to this said ship, Captain, that is endeavering to gather all they News the[y] Can, to send Boston People, an account that they truths, I shall revail, will be of Little Use unless the Gentlemen, in Boston that, I shall Mention, be Brought on Tryall for there Misdenavours, as I shall Lay before your Lordships, that Tea affair, and all there Scheems, and Plans Concerning there Troops in they Country, Whereas they a Generall, and Captain and all other Officers to head there, troops at a Minutes Warning, as there is one Evedince in the Ship I should be Glad your Lordships Would Please to Examine him . . .

This document the sailor signed with “Sam. Dyer,” not just his initials—he could write his name after all.

On August 2, the Captain “Moored at Spithead,” on the south coast of England.[12] In London, the Admiralty Office received Adm. Montagu’s report that he had brought over Dyer “by the desire of the Governor and Colonel Maddison, for endeavouring to entice the Soldiers to desert.” The Admiralty quickly passed on those depositions, and the legal and political headaches they brought, to Lord Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for North America, asking to know “his Majesty’s pleasure, whether the said Dyer should be detained, or set at liberty.”[13]

While he was in Newport, Dyer claimed that as soon as his ship arrived in England “he was sent speedily under a strong Guard to London, & carried before Lord North & examined, who said he was a Rebel & should be hanged.”[14] Or, according to another report, that he “was sent up to London in irons, and examined three times before Lord North, Sandwich and the Earl of Dartmouth, respecting the destruction of the Tea.”[15] Or even that he underwent an “Examination in London before the privy Council.”[16] All those claims were false. None of the British ministers wanted anything to do with him.

When the papers arrived from the Admiralty Office, Undersecretary of State John Pownall quickly passed that news up to Lord Dartmouth. Then Dyer’s own letter arrived, pleading for support and hinting at further information. On August 4, Pownall twice visited Thomas Hutchinson, former royal governor of Massachusetts, to consult with him on the situation. He brought Dyer’s letter, which Hutchinson “thought carried marks of madness.”[17] The former governor wrote in his diary:

Mr. P. seemed in great distress from a prospect of trouble which it was likely he should meet with; for the last accounts are that Dyer informi’g says he has other witnesses on board of treasonable practices by [Samuel] Adams, [William] Molineux, [Dr. Thomas] Young, and what is more strange, Judge Wear of New Hampshire. I thought there was no more difficulty now to get rid of this affair than when they had so many witnesses examined, proving Treason against all but one of the same persons in the affair of the Tea, upon which there had been no further proceeding; however, he determined there was no avoiding to send for Dyer.

Contrary to Hutchinson’s assessment, back in February the government’s top lawyers had decided the available evidence about the Tea Party was too weak for any prosecution.

Pownall also checked in with one of those lawyers that Thursday evening: Attorney General Edward Thurlow. He told the undersecretary that “Dyer’s case [was] a foolish unconsidered proceeding on the part of General Gage and Admiral Montagu. No facts are charged on him or others for which they could be tried or prosecuted here. All Dyer says about the destruction of the tea is mere hearsay. He should be immediately released.”[18]

At nine o’clock that evening, Dartmouth and his staff at Whitehall happily prepared their response to the Admiralty. “I have not failed to lay before the King Your Lordships Letter to me,” the Secretary of State began—though mentioning “the King” might have been only a formula for consideration at high levels of government rather than personally involving George III. Dartmouth told his Admiralty colleagues:

I am to acquaint Your Lordships, that it appears, upon a full Examination of the Papers inclosed therewith, that there is no reason, from any Facts stated in the said Papers, for detaining the said Dyer on board His Majesty’s Ship Captain. There seems, however, to be no objection to his being told, that if he has any thing to communicate to me, relative to public Transactions in the Province of Massachusetts Bay, I shall be ready to receive such Communication.

That letter was sent off to the Admiralty Lords at 8:50 on the morning of August 5.[19]

Though Dartmouth left open the possibility of receiving more testimony from Dyer, he and all those other royal officials seem to have just wanted the man to go away. Montagu no doubt felt he had performed a great service in getting his testimony down on paper. But Gage would later say, “Nobody Supposed that he could give any Material Intelligence of Transactions here,”[20] and Hutchinson judged the admiral’s deposition “very imprudent.”[21] Even before testing Dyer’s evidence against the facts in Boston, Thurlow realized that it offered no legal grounds for holding the sailor or pursuing others. American Patriots were loudly accusing royal officials of trampling on people’s rights, but those officials strove to adhere to British law.

Dyer probably spoke the truth when he told Newporters that “he was discharged [from the Captain] as if he had been only one of the people who were alldischarged the ship being paid off & laid up.”[22] Indeed, he may have worked as a common sailor during at least part of the passage. Dyer was now free, perhaps with a bit of money in his pocket—though he claimed not to have received “one farthing of wages.”[23] Instead of finding a new ship back to America, however, Dyer set out for London. But he never spoke to Lord Dartmouth. Instead the sailor met with Sheriff William Lee, a native of Virginia, and probably other sympathetic officials ready to entertain his story of being kidnapped. Only then did Dyer make plans to return to Boston.

At the end of the month, on August 28, Lord Dartmouth’s office was concerned enough about Dyer to send a private letter to General Gage mentioning him. Unfortunately, that document is lost—one of the very few letters between Gage and Dartmouth that does not survive on either side of the correspondence. We have only Gage’s reply, dated October 30 and marked “private”—the one surviving letter classified that way in the governor’s 1774 missives to the ministry. Gage said that he had received his lordship’s letter about Dyer just two days before, long after the sailor had returned. He blandly recounted Dyer’s accusations and attack on the army officers before reporting that the would-be assassin had “made off to the Congress sitting at Cambridge where he was apprehended and is now in the jail of this town. He appears to be a vagabond and enthusiastically mad.”[24]

General Gage concluded that letter with an explanation for why he was operating so carefully even when his officers were under attack:

affairs are at such a pitch through a general union of the whole that I am obliged to use more caution than would otherwise be necessary, lest all the continent should unite in hostile proceedings against us, which would bring on a crisis which I apprehend His Majesty would by all means wish to avoid unless drove to it by their own conduct.[25]

In other words, the general wanted to avoid giving the Patriots any reason for outrage. Instead, he was waiting for them to go too far so he could strike back from the moral high ground.

Of course, both Gage and Dartmouth understood that if the Patriots had known all that their government had done on this matter, they would have had plenty of grounds for protest. The army really had grabbed a man and put him on board a navy ship to sidestep his right to a trial in Boston. The Samuel Dyer affair had involved the highest levels of the royal government: the governor of Massachusetts and army commander for North America, the navy’s ranking rear admiral in America, the Admiralty Board, the Secretary of State and his undersecretaries, the former governor of Massachusetts, and the Crown’s Attorney General. At a formal level at least, the matter had been laid “before the King.” But Gage was the only person in Boston to learn about any of that business in London, and he kept quiet.

The Massachusetts Patriots decided that Dyer, despite his letter from Sheriff Lee and the endorsement of Dr. Thomas Young in Newport, was probably insane and clearly unreliable. They had championed his cause for a few days, and then he had tried to murder two officers in broad daylight. After that, Boston’s political leaders decided that Dyer was crazy, and that they were as lucky as Lieutenant Colonel Cleaveland in escaping the effects of his rash actions. The Patriots let the sailor stew in the town jail through the winter, the local courts still shut down.

In April 1775, war broke out with the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Provincial militia regiments besieged Boston and reorganized themselves into a New England army. On June 17, British troops forced that army back off the Charlestown peninsula at the cost of hundreds of dead and several hundred more wounded.

In the wake of that Battle of Bunker Hill, the British military cracked down on potential spies inside Boston. On June 19, sailors detained Peter Edes, the eighteen-year-old son of Benjamin Edes, who was now printing the militant Boston Gazette for the Patriots outside Boston. Young Edes was put into Boston’s jail, which had come under the control of the military government.[26] Ten days later, the schoolteachers John Lovell and John Leach joined him there. British officers had found a letter containing sensitive information on Dr. Joseph Warren’s corpse after Bunker Hill; evidently it came from a teacher using the initials “J. L.,” so the army arrested both Lovell and Leach on suspicion. (Warren’s correspondent was Lovell.)[27]

Peter Edes and John Leach kept diaries of their weeks in the Boston jail.[28] Many of their entries are the same, showing they collaborated to record what they saw as abuse rather than to preserve their individual personal thoughts and experiences. Samuel Dyer resurfaces in those journals—and he was once again cooperating with his captors.

The provost martial in charge of the British military’s prisoners was a man from New York, William Cunningham. He had been one of the Sons of Liberty a few years before, but by 1775 he was a fervent Loyalist, brawling with his former comrades. In June he was attacked and run out of the city. Cunningham would work for the king’s army throughout the war before becoming a prison warden in Gloucestershire.[29] On August 9, Edes’s diary complained: “a poor painter, an inhabitant, was put in the dungeon and very ill used by the provost, and his deputy, Samuel Dyer; then the provost turned him out and made him get down on his knees in the yard and say, God bless the King.”[30]

In less than a year, Samuel Dyer had moved from attacking Crown officers to working for one, from complaining about being mistreated as a prisoner to lording over prisoners (even as he technically remained a jail inmate himself). No doubt the sailor had felt betrayed by the Massachusetts Provincial Congress after those Patriots turned him over to the authorities. But he also had a pattern of shifting allegiances, cooperating with whoever in the area appeared to be most powerful. And there is the real possibility, which many people at the time found easy to believe, that Dyer was insane.

Leach and Edes set down two recurring complaints about Dyer, Cunningham, and their guards. The first was profanity. In early July they stated: “a complicated scene of oaths, curses, debauchery, and the most horrid blasphemy, were committed by the provost martial, his deputy and soldiers who were our guard, soldier prisoners, and sundry soldier women confined for theft &c.” On August 13 the prisoners were confined to their rooms with “much swearing and blasphemy close under our window the whole day, by the provost, his deputy, and our guard of soldiers.” Leach and Edes wrote: “It appears to be done on purpose, as they knew it was disagreeable to us to hear such language.”[31]

The provost and deputy’s other sin, according to their captives, was greed. It was common in British and American prisons of the time for inmates to have to pay the jailers certain fees for their upkeep, and those rules were not relaxed in wartime. On August 17 one prisoner was discharged owing a dollar; “he paid a pistareen and left a silver broach in pawn for four more; the provost kept the broach, and gave Dyer the pistareen.” Nine days later Dyer “demanded two dollars” of another prisoner. He received one dollar and “a pillow, porringer, &c. pledged for the other.”[32]

On August 28, Edes wrote, “We complained about Dyer to the Gen. about ill usage.” By this time, General Gage probably sensed that his military and political career was coming to a halt. Samuel Dyer was a loose end from the previous year, still causing headaches. The next day, the British authorities finally brought Dyer to court for assaulting Lieutenant Colonel Cleaveland and Captain Montresor. He was now showing loyalty to the Crown—but he probably also seemed unstable. The upshot: “Dyer tried and acquitted and ordered to depart the province.”[33]

Nonetheless, the sailor stuck around the jail. “Dyer in his glory,” Edes wrote on September 11; “he is the provost’s deputy, and a very bad man.” Four days later the new royal sheriff of Suffolk County, Joshua Loring, Jr., oversaw a mock auction of goods taken from Bostonians’ houses to the prison, with “the provost, his son and Dyer, the bidders—a most curious piece of equity.”[34]

Finally on September 18, Peter Edes could write:

Dyer discharged, to the great satisfaction of the prisoners. He seemed to be a most unhappy, wicked wretch; Lord have mercy on him, for if we may be allowed to judge agreeably to the word of God, he was ripe for destruction, a most awful state.[35]

Samuel Dyer left the Boston jail. With the town besieged, his best prospect was probably going back to sea, either in the Royal Navy or on one of the private vessels bringing in food and supplies. But Dyer’s fate remains his final secret.

[1]“King vs Dyer”: Invoice, July 5, 1774, vol. 123, Thomas Gage Papers, Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

[2]“Lieutenant Colonel Maddison prevailed”: Gage to Dartmouth, October 30, 1774, Colonial Office, Great Britain, Documents of the American Revolution, 1770–1783,K. G. Davies, editor (Dublin: Irish University Press, 1975), 8:222.

[3]“at 5 came on board”: log of H.M.S. Captain, July 7, 1774, ADM 51/158, Part VII, National Archives, UK.

[4]“Man who had been carried”: Stephen Kemble, journal, October 18, 1774, Collections of the New-York Historical Society, 16:39.

[5]Dyer’s statement to Montagu: Samuel Dyer deposition, July 30, 1774, CO5/120, ff. 251–2, National Archives, UK.

[6]Mouat’s statement to Montagu: Samuel Mouat deposition, July 30, 1774, CO5/120, f. 253, National Archives, UK.

[7]“often threatened”: Ezra Stiles, The Literary Diary of Ezra Stiles, D.D., Ll.D., Franklin Bowditch Dexter, editor (New York: Scribner’s, 1901), 1:462.

[8]John Hood: Connecticut Courant, January 25, 1774.

[9]“Captain Conner”: Benjamin L. Carp, Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America(New Haven, Yale University Press, 2010), 128.

[10]“Running up Channell”: log of HMS Captain, July 31, 1774, ADM 51/158, Part VII, National Archives, UK.

[11]“From On Board”: Dyer to Dartmouth, July 31, 1774, CO5/120, f. 255, National Archives, UK. See also “Entry of” Dyer’s letter, CO5/247, ff. 210–1.

[12]“Moored at Spithead”: log of HMS Captain, August 2, 1774, ADM 51/158, Part VII, National Archives, UK.

[13]“by the desire of the Governor”: CO5/120, f. 247, National Archives, UK.

[14]“he was sent speedily”: Stiles, Literary Diary, 1:462.

[15]“was sent up to London”: Essex Gazette, October 25, 1774.

[16]“Examination in London”: Gage to Dartmouth, October 30, 1774, Colonial Office, Documents, 8:222.

[17]“thought carried marks of madness”: Thomas Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters of His Excellency, Thomas Hutchinson, Esq., Peter Orlando Hutchinson, editor (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1884), 1:205.

[18]“Dyer’s case”: Dartmouth, The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth: Volume II, American Papers, Historical Manuscripts Commission, 14th Report, Appendix, Part 10 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1895), 220.

[19]“I have not failed”: CO5/120, f. 257-7a, National Archives, UK. See also entry of Dartmouth’s letter to the Admiralty, CO5/250, f. 164.

[20]“Nobody Supposed”: Gage to Dartmouth, October 30, 1774, Colonial Office, Documents, 8:222.

[21]“very imprudent”: Hutchinson, Diary and Letters, 1:207.

[22]“he was discharged”: Stiles, Literary Diary, 1:462.

[23]“one farthing of wages”: Essex Gazette, October 25, 1774.

[24]“made off to the Congress”: Gage to Dartmouth, October 30, 1774, Colonial Office, Documents, 8:222.

[25]“affairs are at such a pitch”: Gage to Dartmouth, October 30, 1774, Colonial Office, Documents, 8:223.

[26]Peter Edes arrested: Samuel Lane Boardman, editor, Peter Edes: Pioneer Printer in Maine(Bangor: De Burians, 1901), 93–4. Edes’s prison diary appears on pages 93–110.

[27]Lovell and Leach arrests: Papers of John Adams, Robert J. Taylor, editor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1979), 3:69, 76. The Political Magazine, and Parliamentary, Naval, Military, and Literary Journal, 1 (1780), 757.

[28]John Leach diary: John Leach, “A Journal Kept by John Leach, During His Confinement by the British, in Boston Gaol,” New England Historical and Genealogical Register, 19 (1864), 255–63. Reprinted in Boardman, Peter Edes, 115-25. Leach’s entries are often more full and personal than Edes’s, but fewer entries survive.

[29]William Cunningham: Thomas Jones, History of New York During the Revolutionary War, Edward Floyd de Lancey, editor (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1879), 484. Henry B. Dawson, Reminiscences of the City of New York (New York: 1855), 39–40. J. R. S. Whiting, Prison Reform in Gloucestershire, 1776-1820: A Study of the Work of Sir George Onesiphorus Paul, Bart. (London: Phillimore, 1975), 21.

[30]“a poor painter”: Boardman, Peter Edes, 99.

[31]jailers’ profanity: Boardman, Peter Edes, 96, 100, 116, 120. There are many more complaints about swearing that don’t specifically mention Dyer.

[32]jailers’ fees: Boardman, Peter Edes, 101–2, 104, 121–2.

[33]complaint to general and acquittal: Boardman, Peter Edes, 105.

[34]Dyer at mock auction: Boardman, Peter Edes, 107.

[35]Dyer discharged: Boardman, Peter Edes, 108.

2 Comments

Terrific detective work – a most enjoyable history of a most disagreeable fellow.

Thank you. Dyer’s main redeeming quality might be that he was willing to betray everyone equally.