Captain Johann Ewald had much to thank the Almighty for.[1] A heroic stand on the picket line before Norfolk, Virginia, parried an American thrust and covered the captain and his men with glory, but it had nearly cost him his leg and left him bed bound and bereft of the command of his beloved Jӓgers. Returning to them without a limp after a three-months recovery, Ewald “found the greater part of the Jӓgers had pieces of cowhide around their feet in place of shoes, which they showed me with laughter.” Ewald marveled “how the German soldier . . . despite his strict discipline, never grumbles when he is alone and makes the best of everything.”[2]

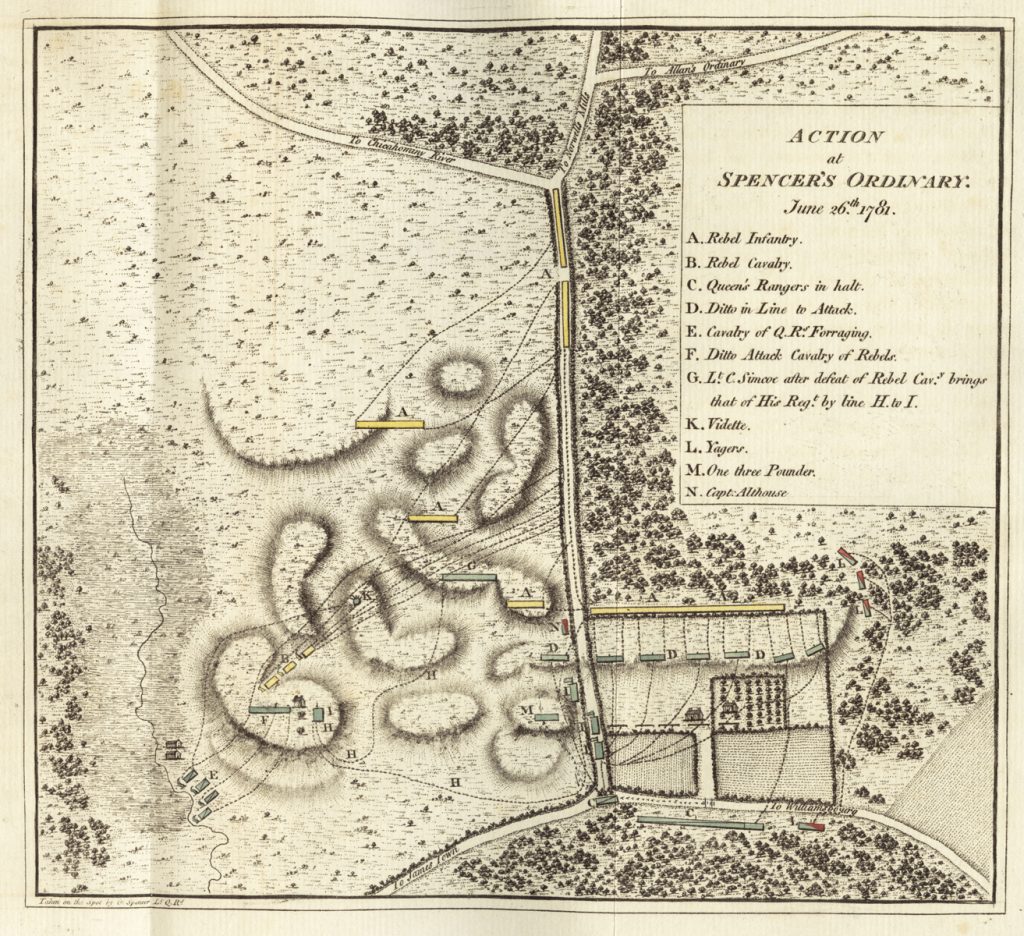

Now, taking post near a crossroads on the road to Williamsburg, the Hessian captain longed only to sleep. No sooner had he closed his eyes than gunfire erupted to his left front. Springing upward, Ewald demanded to know the source of it. Hushed back to sleep by assurances that it needn’t worry him, Ewald closed his eyes once again only to rise as the volume of fire intensified. Rousing his Jӓgers, the captain rode with two men into a nearby orchard only to stumble upon a blue-coated Frenchmen of Armand’s Legion, who reported the Americans to be “Very near, sir!” Confirmation came as no more then “three hundred paces away, just on the point of moving forward,” a battle line materialized.[3] American General Lafayette’s advance guard was before him, in force, readying to sweep Ewald and his men from the crossroads of Spencer’s Ordinary, Virginia. What followed this day, June 26, 1781, gave him even more reasons to count his blessings.

“Lord Cornwallis has not . . . explained himself clearly enough.” Movement to Contact, June 1781

This clash of arms in the morning dawn came unexpectedly to the country round Virginia’s ancient capital of Williamsburg. Now in the high summer of 1781, the British army commanded by Gen. Charles, Earl Cornwallis had suddenly given up its chase of the Marquis de Lafayette’s forces for a withdrawal down the peninsula towards Williamsburg. His enemy’s retrograde movement after so many weeks of advancing left Lafayette justifiably perplexed about Cornwallis’s intentions. “In this country,” he complained to Alexander Hamilton, “there is no getting good intelligences,” a problem which plagued him well into June. Caution guided his movement, even after a brigade of Pennsylvania Continentals under Brig. Gen. Anthony Wayne arrived in the middle of the month to bolster his numbers. “Lord Cornwallis has not, as yet, explained himself clearly enough,” the twenty-three-year-old Lafayette confessed on June 25, “to determine upon his immediate objectives.”[4]

Guessing Williamsburg as Cornwallis’s destination, Lafayette turned to Wayne to head the advance against him, recommending—on June 22—the formation of an advanced corps under Col. Richard Butler’s command.[5] The Dublin born Butler was to be the spear in Wayne’s hand. Second in prestige only to Wayne himself among the warrior sons of Pennsylvania, Butler had helped Daniel Morgan forge the feared riflemen of Saratoga and carried the leftward column over the palisades at Stony Point. When the mutiny of January 1781 wracked the Pennsylvania line, Butler stood side by side with Wayne and bravely stemmed the tide of mutiny. To contemporaries Butler remained an “officer of superior talent” from his first commissioning in 1776 to the day he left his bones on the banks of the Wabash.[6] So it was that he wrote, “on the 24th I was sent out with a small Advanc’d light Corps, to try to strike the British rear.” About forty-eight hours later, a sleep deprived Butler finally caught up with the enemy.[7]

Simcoe’s Detachment: June 24-26, 1781

That enemy found itself detached from the main army, ordered out by Cornwallis the same day Butler began his march, to scour the banks of the Chickahominy river and torch any rebel foundries and boats they found lurking in the vicinity. Neutralizing these assets walked hand in hand with the herding of cattle from farms local to Williamsburg for the nourishment of Cornwallis’s army. Two particular officers came to the Earl’s mind, old friends who had made themselves masters of partisan warfare.[8]

Command of the detachment fell on the shoulders of the twenty-nine-year-old lieutenant colonel of the Queen’s Rangers: John Graves Simcoe. An officer of the regular army at the war’s outset, Simcoe grew into the rough and tumble role of a partisan commander whilst maintaining the gentlemanly decorum instilled within him by the masters of Eton and Oxford. “A man of letters,” one American adversary noted, “enterprising, resolute, and persevering”; a commander who carefully planned his missions, and when in the field seized “upon every advantage which offered in the course of execution.” He assumed command of the Queen’s Rangers in the fall of 1777 and set about grafting them to his will. Raised by the famed Robert Rogers, these loyalists in arms bore upon their backs distinctive green jackets and boasted eleven companies, replete with grenadiers and light infantry on the flanks, and a cadre of highlanders bedecked in bonnets with a piper to play them pibrochs around the campfire.[9] Under Simcoe’s hand they added a mounted element for greater tactical mobility, a crucial asset in the war of outposts upon which they were frequently engaged, and infused them with a tactical doctrine that favored an aggressive “use of the bayonet.” Indeed, Simcoe urged upon his new men “a total reliance upon that weapon.”[10]

Simcoe’s companion was a one-eyed captain of a company of Hessian Jӓgers whose first taste of this American war in 1776 was almost his last. Captain Johann Ewald had “wished for nothing more then to get to know the enemy” and within twenty-four hours of first setting foot on American soil he met them. Courting ruin by stumbling with a single company into several American battalions, the captain quickly wised up to the ways of this new war. His Jӓgers were literal hunters, rifle-armed woodsmen renowned for their accuracy and individualism, who donned green coats and marched to war with the blast of the hunting horn ringing in their ears.[11]

The offensive minded Simcoe worked well with Ewald whose own dictums on partisan warfare stressed that if a commander “be forced . . . to give battle . . . one must not hesitate for long but speedily make one’s dispositions and attack” the enemy “with saber in hand and bayonet mounted even if the enemy be twice as strong;” for “he who attacks first,” Ewald reasoned, “has the victory already half in his hands,” and fortune—the soldier’s friend—“is usually on the side of the most decisive and courageous.”[12]

Decisiveness and courageousness—two attributes most needed now. As Cornwallis hastened towards Williamsburg, Simcoe’s command hovered along the banks of the Chickahominy, finding “little or nothing to destroy,” but plenty of cattle. Disappointed, Simcoe soon had greater worries. The bridge spanning Diascund Creek, a tributary of the river, was no more. Rebuilding it would be a time consuming and hazardous process with the exact whereabouts of the Americans unknown. Like Lafayette, Cornwallis’s “general intelligence,” Simcoe “knew to be very bad.”[13] Assured by Cornwallis that should they come to trouble he would decamp from Williamsburg in full array, ready to pounce on their pursuers, the detachment nevertheless remained vigilant throughout June 25.

Crossing the creek after some hasty repairs, Simcoe consolidated his command and reordered the line of march. Ewald pressed on to the crossroads at Spencer’s Ordinary with his Jӓgers and the flank companies of the Rangers. The main body followed on behind under the command of Maj. Richard Armstrong—“a very good man and nothing more,” as Ewald described him. Still further back, the cattle and their herders—a handful of North Carolina loyalists that followed Cornwallis to Virginia—pressed their burdens forward, while the ever-vigilant Simcoe hugged the rear of the column with his cavalry and highlanders.[14]

Marching through the night and early morning, the British came at last to the open fields housing the tavern known locally as Spencer’s Ordinary around 7 o’clock on the morning of June 26, 1781. Fifteen hours earlier, Wayne had decided to cast Butler’s spearhead against those very same crossroads, informing Lafayette that “Colo. Butler will advance to the fork of the road leading to James Town and Williamsburg, as the only chance of falling in with this Cattle Drove. I shall advance to support him.”[15] The die, it seemed, was now cast.

“God be praised that I did not lose my head.” The Skirmish Begins

By 7 o’clock in the morning, Simcoe had at last arrived at Spencer’s Ordinary, a quaint tavern nestled upon plowed fields forged from an open expanse of ground abutting the angle created by the divergence of the highway from Norell’s Mills. Framed by dense woods to the east and the high ground to the north, the open ground around the tavern was cut through by a secondary road surging eastward towards Williamsburg and the beckoning safety of Cornwallis’s army some six miles away. Upon this thoroughfare Ewald and Armstrong’s infantry companies “camped in platoons . . . breakfasted, and rested.” Surveying the open ground to their front, Simcoe dubbed it “an admirable place for the chicanery of action.”[16] Continuing on to the southwest the main road carried itself on to Jamestown and the broad banks of the river whence Virginia’s founding settlement took its name; beyond it in the open country to the west, farms nestled amidst the scattered hills affording Simcoe’s cavalry the opportunity to graze their horses and bring in a few more cattle lurking in the area. The fences lining either side of the road were torn down, allowing greater access to the avenue should the need arise.[17] The need came when the Americans suddenly came thundering down the lane.

“After three days and night successive march,” Butler remembered “I got up with Simcoe.” His ad hoc command consisted of all elements of Lafayette’s army: Pennsylvanians and Continental Light infantry, and veteran Virginia riflemen eager to meet the enemy “who were robbing the country of cattle.”[18] Chasing them had been an exhausting and gruesome business, as lining the road in Simcoe’s wake Lt. Willam Feltman noted a “negro man with the small-pox lying on the road side,” a frequent practice, he claimed, in order to deter pursuit. Many others “in that condition starving and helpless, begging of us,” the young officer candidly reported, “to kill them as they were in great pain and misery.”[19]

Fearing that Simcoe was moving too fast for them, it was thought the British could only be brought to heel by Maj. William MacPherson’s dragoons, the last remnants of the mounted legions of Pulaski and Armand, “who were not only in number entirely inadequate for reconoitring duty,” one Virginian explained, “but were worn down by incessant fatigue.” Still, when tasked with chasing down Simcoe’s rear that morning, their strength boosted by the mounting of some fifty continentals behind them, they went forward boldly enough.[20] MacPherson’s riders quickly outstripped their infantry support, and consequently came into action well before them. Their coming was announced by an eruption of shots from the eagle-eyed ranks of the Queen’s Rangers Highland company, standing as sentinels amidst the trees bordering the roadside, and with the sudden burst of Trumpeter Bernard Griffiths’ trumpet adding to the tumult. Wheeling his mount around, Griffiths hurried to alert his mounted comrades of the unexpected threat. Reaching his comrades, he bellowed frantically: “Draw your swords, Rangers, the rebels are coming!”[21] Galvanized, the Rangers countercharged and burst among their enemies with a ferocity that undid them. MacPherson was dismounted in the first instance and evaded capture only by hiding in a nearby swamp. In an instant Butler’s mounted arm was shattered; his infantry would have to carry the day alone.[22]

The eruption of fighting off to the left startled Ewald from his blankets. Jumping up, he hastened his men to arms before embarking upon his personal reconnaissance that nabbed him the equally startled French dragoon. Simcoe, meanwhile, riding furiously to the west, arrived just in time to see his cavalry chasing MacPherson’s troopers back up the road. Bringing them under his control, Simcoe dispatched what remained of the cattle down the road towards Williamsburg, while ensuring that a line of retreat southeastward to Jamestown remained opened to him by deploying his one remaining cannon. To the east, holding the right wing of their paltry army, Ewald swung his three-company command into action at the battle’s outset with dauntless skill. “While Ewald lives,” Simcoe pronounced to those around him “the right flank will never be turned.”[23] Such confidence was not misplaced.

By this time of the war, Capt. Johann Ewald had seen and done it all. In snow and heat he had marched and fought and won and lost and suffered wounds in a war the Landgrave deemed worthy of his service. Friends had fallen in bloody heaps before his eyes, generals had ridiculed his conduct and exulted him as amongst the bravest in the army, and through it all he had honed his art to a blinding sheen. Yet in this supreme moment he did not baulk from admitting the difficulties of remaining calm. “Thank God I did not lose my head,” he remembered. To his front a battle line arrayed itself beyond the treeline. Sword in hand Ewald placed himself at the head of Simcoe’s flankers, his own Jӓgers scurrying into the woods to the right in a bid to hammer the American flank just as their captain met it head on. The opening salvo from the Americans dropped “two-thirds of the grenadiers” but the survivors rushed on and followed Ewald “like obedient children” until “we came among them . . . hand to hand.”[24]

The sudden onrush from front and flank drove the Americans from the tree lined slope. It was but a momentary success. “Had we taken one backward step,” Ewald knew, “the courage of the enemy would have redoubled while that of the soldiers on our side would have forsaken them.” There was nothing left to do but press forward. Regrouping his companies, Ewald received reinforcements as Major Armstrong’s Rangers came into action on his left, “advancing as fast as the ploughed fields they had to cross would admit,” Simcoe noted proudly.[25]

With his left secured, Ewald probed deeper into the woods just as one of his Jӓgers “whispered softly in my ear that an entire column of the enemy was approaching at the quick step” up a footpath. Of his own accord the bold captain went several paces ahead—and suddenly ran into people. “I could not help myself” he remembered “and cried ‘Fire! Fire!’,” igniting a firefight that scorched the trees and riddled men’s bodies “for several minutes.”[26]

The burst of fire all along his infantry’s line of battle impressed upon Simcoe the desperate situation his meager force was in. Eyes fixed upon the enemy to their front, Simcoe’s infantry could not perceive the growing threat emerging down the roadside to their left. The Americans were once again pressing down the road, beyond Armstrong’s leftmost company; survivors among the officers engaged would later insist that the Rangers had “begun to give way” and that a decisive push round the flank would seal the deal. That opportunity never came came as Simcoe’s riders once again threw themselves into the fray, sabers in hand, crashing into the oncoming enemy foot and driving them once more up the road, just as those in contact with Armstrong and Ewald’s infantry broke contact.[27]

In the subsequent lull Simcoe wasted no time in preparing his men to retreat. His original intention of “checking the enemies’ advance till such times as the convoy was in security” had long been surpassed. Now in this period of grace afforded by the American withdrawal, Simcoe gathered his wounded in Spencer’s tavern and made haste down the road towards Williamsburg where within two miles they met Cornwallis’s leading elements and returned to the field to collect their wounded. By day’s end Cornwallis’s army was secured within Williamsburg, feasting off the prime beef of Virginia.[28]

Both sides claimed victory, with Butler himself swearing that he had given Simcoe “a handsome stroke, with little loss myself.” His recollection of the skirmish is unfortunately nowhere near as detailed as his adversaries, for the fatigue of the march and the subsequent action left him overcome with “a violent fever and diarrhea, which had like to take me off” had his constitution failed him.[29] It was two weeks before the colonel’s health was restored enough for him to revisit the action in official correspondence, by which point the paltry skirmish must have seemed vague and far away.

For Simcoe and Ewald both, the affair that day was far more memorable. Surprised though they had been, the pair had fought off ruin with levelheaded coolness and Spartan bravery, and with the intuitive understanding of each other’s abilities and the capabilities of their men forged through a long operational partnership and personal friendship. Though out of personal contact for most of the action, Ewald and Simcoe were able to launch a relatively coordinated and aggressive counterattack that parried, retarded, and ultimately checked the American blows that descended upon them. Butler’s ad hoc command, by comparison, though drawn from veteran elements had only come together as a combined force in the days immediately before the action, went forth bravely and with determination but did not possess the long-standing relationship of the Queen’s Rangers and Hessian Jӓgers. In staving off disaster, Simcoe could justifiably claim Spencer’s Ordinary as “an honorable victory earned by veteran intrepidity.”[30]

[1]Johann Ewald, Diary of the American War. A Hessian Journal, trans. Joseph P. Tustin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 289-291. In the action at Scott’s Creek on March 19, 1781, Ewald was “wounded in the knee” and feared that “the bone and large tendon must have been injured.” Ibid., 290. Ten days later he rejoiced after having been able to sleep for the first time in over a week after pus was drained from his wound. “Up to now,” he reported “I ran the risk of losing my leg, since the upper part of the bone . . . was damaged, and the main tendon of the large muscle in the knee hung only by a thread.” Ibid., 294. His patience paid off, enabling him to lead his Jӓgers to their destiny at Yorktown.

[4]Marquis de Lafayette to Alexander Hamilton, May 23, 1781, founders.archives.gov/documents/Hamilton/01-02-02-1175; Charles Cornwallis to Henry Clinton, May 26, 1781, Correspondence of Charles, First Marquis Cornwallis, ed. Charles Ross (London: John Murray, 1859), 1:100-101.

[5]Lafayette to Anthony Wayne, June 21, 1781, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution. Selected Letters and Papers, 1776-1790. Volume IV, April 1, 1781-December 23, 1781, ed. Stanley J. Idzerda (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 206-207; Richard Butler to William Irvine, July 8, 1781, in The Pennsylvania Archives. Fifth Series, Volume III, ed. Thomas Lynch Montgomery (Harrisburg: Harrisburg Publishing Company, 1906), 5.

[6]On Richard Butler see: Simon Gratz, “Biography of General Richard Butler,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Volume VII(Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1883), 7-10; Anthony Wayne to George Washington, February 27, 1781, in Charles J. Stille, Major General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line in the Continental Army (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippencott, 1893), 262; Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the American Revolution, Illustrative of the Talents and Virtues of the Heroes and Patriots, who Acted the Most Conspicuous Parts Therein (Charleston: E. Miller, 1828), 2:72.

[7]Butler to Irvine, July 8, 1781. Pennsylvania Archives, 5.

[8]John Graves Simcoe, Simcoe’s Military Journal. A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps, called the Queen’s Rangers, commanded by Lieut. Col. J. G. Simcoe, during the War of the American Revolution (New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844), 225. Ewald, Diary, 306. Both Ewald and Simcoe’s units had been acting as Cornwallis’s left rear since June 22; Tarleton’s legion formed the same service on the right, his flank inclined towards the Pamunkey River. Banastre Tarleton, A History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America(1787; reis., New York: New York Times, 1968), 308.

[9]Simcoe, Military Journal,19-21.

[11]Rodney Atwood, The Hessians (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980), 45; Ewald, Diary, 56. See note 170 on page 388 for further information on the Jӓger hunting horns.

[12]Simcoe, Military Journal, 21; Johann Ewald, Treatise on Partisan Warfare, trans. Robert A. Selig and David Curtis Skraggs (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1991), 79-80. Ewald and Simcoe and their units had often operated together, so that a brotherly bond had developed between the Rangers and Jӓgers by the summer of 1781. That bond was further strengthened by their stand at Spencer’s Ordinary.

[13]Simcoe, Military Journal, 226.

[14]Ibid., 226-227; Ewald, Diary, 306-308.

[15]Wayne to Lafayette, June 25, 1781, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 211.

[16]Ewald, Diary, 308; Simcoe, Military Journal, 227.

[17]Simcoe, Military Journal, 227-228.

[18]Benjamin Colvin Pension Statement, in J.T. McAllister, Virginia Militia in the Revolutionary War (Hot Springs, VA: McAllister Publishing Co., 1913), 108.

[19]Journal of Lieut. William Feltman, of the First Pennsylvania Regiment, 1781-1782 (Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1853), 6. Thousands of blacks had attached themselves to Cornwallis’s army, seeking refugee from bondage. Simcoe’s treatment of the infected may seem harsh, but smallpox could easily spread and ravage his humble command. Another explanation is that these folk could not keep up and simply fell behind the line of march. Either way, theirs was an unenviable fate.

[20]John F. Mercer to Col. Simms, in Fragments of Revolutionary History, ed. Gaillard Hunt (Brooklyn: The Historical Printing Club, 1892), 36; Butler to Irvine, July 6, 1781, Pennsylvania Archives, 5; Journal of Lieut. William Feltman, 6.

[21]Simcoe, Military Journal, 228.

[22]Lafayette, probably on information received from Butler, claimed that MacPherson “overtook Simcoe, and regardless of numbers made an immediate charge.” Lafayette to Tomas Nelson, June 28, 1781, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, 217-218. American prisoners told Ewald after the fight of their firm belief that MacPherson’s charge was “responsible for our misfortune. He had showed himself too early and been unhorsed by our cavalry.” Ewald, Diary, 312.

[23]Simcoe, Military Journal, 232.

[25]Ibid., 312; Simcoe, Military Journal, 231.

[27]Mercer to Simms, Fragments, 42-43; Simcoe, Military Journal, 232-233.

[29]Butler to Irvine, July 8, 1781, Pennsylvania Archives, 5.

2 Comments

Good overview.

It is interesting to note that this small battle was universally called the battle of Hot Water by Continental and Virginia forces, at the time of the battle and in pension applications. This is because most of the battle was fought on the land of a plantation called Hot Water, owned at the time by the Ludwell family, which owned it until 1796. Cornwallis and Lafayette do not give any name to the fight in their contemporary correspondence. No American account at the time mentions Spencer’s Ordinary. Nor do two contemporary maps of the campaign – one British, one French – give the action any name. (“March of the Army under Lieut. General Earl Cornwallis in Virginia,” in Idzerda, Lafayette, 4:232; and Captaine Michel du Chesnoy, “Campagne en Virginie du Major Général M’is de LaFayette: ou se trouvent les camps et marches, ainsy que ceux du Lieutenant Général Lord Cornwallis en 1781,” undated, in Idzerda, Lafayette, 4:295.)

I have searched high and low but have found no explanation about why it was called Hot Water.

Is there an order of battle for Lafayette’s army at the time or this battle?