General Anthony Wayne was one of the most capable generals in the Continental Army and is perhaps best remembered for his successful surprise attack that captured the British post at Stony Point, New York, on July 16, 1779. Wayne also suffered his share of reverses, most notably at Paoli, Pennsylvania, on the night of September 20-21, 1777, when his 2,500 troops were soundly defeated after being caught unaware by Gen. Charles Grey with 1,200 British regulars. As painful as this debacle was, Wayne later suffered another stinging defeat on July 21, 1780, when a handful of Loyalist militia holding a blockhouse at Bull’s Ferry, New Jersey repulsed Wayne’s much larger force of Continentals. Although the battle did not alter the overall strategic situation, it proved embarrassing to the Americans, while the British and Loyalists exulted in their triumph. The event prompted Major John André, Gen. Sir Henry Clinton’s aide-de-camp, to compose and publish a lengthy poem, Cow-chace, ridiculing Wayne and other American officers.

After the failed British efforts to strike a serious blow against George Washington’s army at Connecticut Farms and Springfield, New Jersey, in June 1780, Washington believed that Clinton, having recently returned to New York following his capture of Charleston, South Carolina, would move against the American post at West Point on the Hudson River. Washington therefore in late June moved most of his troops to Preakness, New Jersey, where they would be in a better position to respond to such a threat. On July 6, Washington called a council of war to consider proposals for future operations. Wayne, whose boldness sometimes bordered on recklessness, suggested an attack on New York, but the idea was rejected because the army lacked the strength for an undertaking of that magnitude.[1]

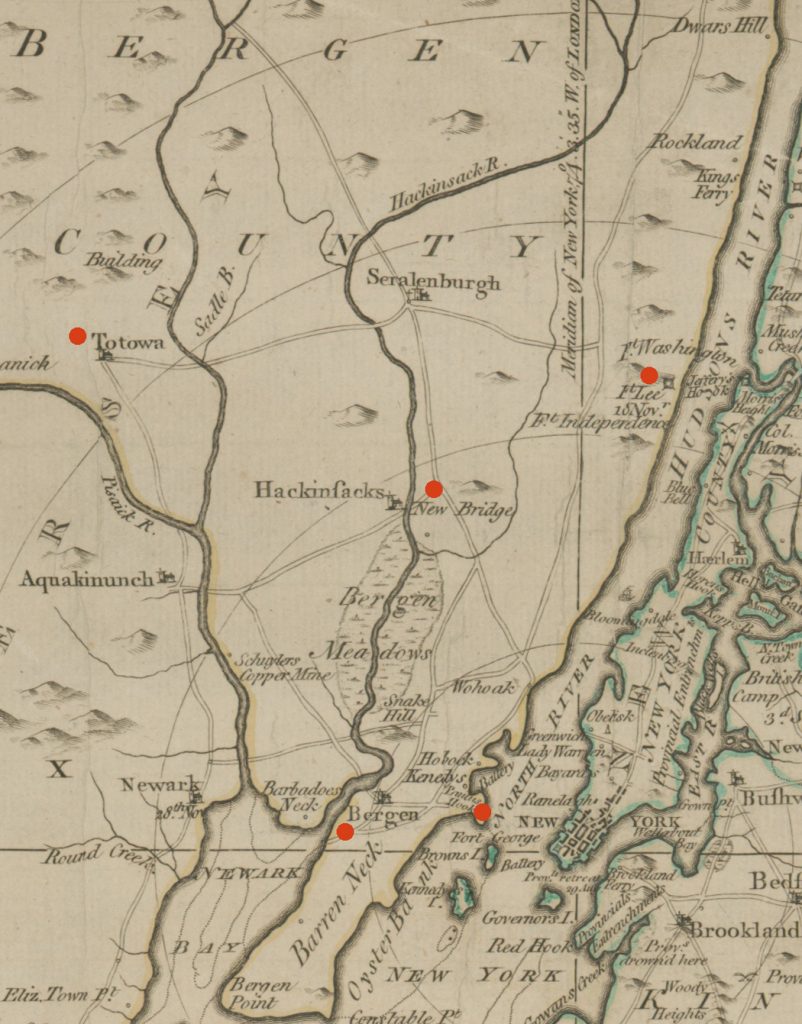

Wayne, encamped with his Pennsylvania Continentals at Totowa, New Jersey, and always eager for action, informed Washington on July 19 that he intended to march the next afternoon with his two brigades, four pieces of artillery, and Col. Stephen Moylan’s 4th Light Dragoons “for the purpose of destroying the blockhouse near Bulls Ferry,” about four miles north of Hoboken, “and securing the cows, horses . . . in Bergen Neck between the Hackensack and North [Hudson] Rivers from Newbridge and Liberty Pole southward.” Wayne stated that he would send parties out before dawn on July 20 to occupy positions where they could observe any British attempts to send reinforcements across the Hudson River. One hundred men and an artillery piece would hold New Bridge, while two infantry regiments “with a few horse” would take post at possible landing sites, one regiment going “to the beach opposite Kings Bridge, the other to Fort Lee.” Should the British attempt a landing at either site, these troops would inform Wayne and defend their positions. Based on his “knowledge of the ground,” Wayne declared that a British landing “is an event more to be wished than dreaded.” Once these detachments had reached their assigned locations, the rest of the American force would “move in two columns to Bulls Ferry—one on the summit of the mountain—the other with the artillery and horses along the open road.” The cavalry would at the same time “push with rapidity towards bergen town & when they reach as low as is necessary, or prudent, begin & Drive off every Species of Cattle & horses moving back with Velocity—whilst another party are advanced to cover them.”[2]

Washington replied the next day, authorizing Wayne to employ the 1st and 2nd Pennsylvania Brigades and Moylan’s dragoons “upon the execution of the Business planned.” The commander-in-chief advised Wayne to dispatch a few of the dragoons that afternoon “to patrol all night, and see that the Enemy do not, in the course of the night, throw over any troops to form an ambuscade.” Washington suggested that the mounted troops “inquire as they go, for Deserters,” to conceal the true purpose of their foray.[3]

At 3 p.m. on July 20, Wayne set out with his two infantry brigades, Moylan’s dragoons, and four artillery pieces “& arrived a little in the rear of New Bridge at 9. in the Evening.” The Americans rested for four hours, resuming their march at 1 a.m. on July 21. The units assigned to guard against prospective British landings, the 6th and 7th Pennsylvania regiments, were detached along the way. Wayne ordered these troops to conceal themselves and “wait the Landing of the Enemy—& then at the point of the bayonet—to dispute the pass in the Gorge of the Mountain at every expence of blood” until they were reinforced. The main force continued marching, then separated according to plan, with General James Irvine moving “along the Summit of the Mountain” with part of his 2nd Brigade and the 1st Brigade under Col. Richard Humpton, the artillery, and Moylan’s dragoons taking “the common road.” Where the road forked with one branch going toward Bergen and Paulus Hook, Wayne left the cavalry and some infantry “to receive the Enemy if they attempted anything from that Quarter.”[4]

Upon reaching their objective, Wayne and his officers examined the blockhouse and surrounding terrain. The structure, they found, was “surrounded by an Abbatis & Stockade to the perpendicular Rocks” along the Hudson River, “with a kind of Ditch or parapet serving as a Covered way.” As they scouted the enemy position, Wayne claimed that the British could be seen “in motion on York Island,” increasing his optimism that they would cross the river and fall into his ambush.[5]

The Continentals deployed for the attack on the blockhouse. Irvine halted north of the post, “in a position from which he could move to any point where the Enemy should attempt to land—either in the Vicinity of” Bull’s Ferry or farther north at Fort Lee. The 1st Pennsylvania Regiment occupied “a hollow way on the north side the block house,” and the 10th Pennsylvania took a position in a similar terrain feature south of the fortification. Wayne ordered the men “to keep up a Constant fire into the port holes” of the blockhouse to cover the artillery and the 2nd Pennsylvania as they advanced from the west.[6] Apparently Wayne had little respect for the defenders; he had often reviled Loyalists, once referring to them as “Refugees & a wretched banditti of Robbers horse thieves & c.”[7]

There were about seventy Loyalists in the blockhouse, a militia company of the Loyal Refugee Volunteers commanded by Capt. Thomas Ward. They had constructed the blockhouse as protection against American attacks while they cut firewood for the British garrison in New York City, a task they performed in exchange for pay and provisions. Two “small Guns” were mounted in the blockhouse, probably swivel guns capable of firing both solid iron balls about one inch in diameter as well as grape shot.[8] Clinton, who visited the blockhouse after the battle, described it as “a trifling work,” intended to protect the Loyalists “against such straggling parties of militia as might be disposed to molest them, not imagining they could ever become an object to a more formidable enemy.”[9] The Loyalists must have received warning of Wayne’s approach, either from their own scouts or local residents, as they had time to take shelter in their fortifications before the American force arrived.

The covering fire from the regiments north and south of the blockhouse enabled the American artillery to deploy at a distance of only sixty yards from the structure. None of the accounts mention the type of guns employed, but they were probably six-pounders, the most common fieldpieces used by both armies. At approximately 11 a.m. the artillery “Commenced a Constant fire,” Wayne reported, “which was returned by the Enemy & continued without Intermission . . . until After 12 OClock.” Despite the intensity of the fire, Wayne claimed “we found that our Artillery had made but little Impression (altho’ well & Gallantly served) the metal not being of Sufficient weight to traverse the loggs of the Block house.”[10]

Wayne may have been too far from the fortification to observe the effect of the fire, or his view may have been obscured by smoke, as in actuality the artillery had badly damaged the blockhouse. Clinton noted that the structure “was pierced by fifty-two Shot in one face only and the two small Guns that were in it dismounted.”[11]

During the bombardment, Wayne received two dispatches from one of his officers, Zebulon Pike (father of the famous explorer of the same name), who was at Closter observing the movements of British troops. The first dispatch, written in the early morning, stated that about 3,000 men had boarded a dozen vessels and appeared to be sailing downriver to New York City. In the second, composed at 9 a.m., Pike wrote that while he could not see the British force on Valentine’s Hill on the New York side of the Hudson, in his opinion they had left that position, as he had observed “about two thousand of the Enemy together with a number of Waggons which appears to be loaded with baggage.” Some eight hundred men of this force had embarked aboard ships and the boarding continued.[12] These messages, and having himself seen what he believed were “many vessels and boats moving up with troops from New York,” Wayne reconsidered his attack on the blockhouse.[13] He hastily convened a council of war, where he and his officers “unanimously Determined . . . to withdraw the artillery & fall back by easy degrees” to New Bridge, “to prevent the Disagreeable consequences of being shut up in Bergen Neck,” Wayne explained.[14] He portrayed the decision more favorably in a subsequent letter to Washington, insisting that the approach of a British relief force “made it necessary to Relinquish a lesser for a much greater Object,” the chance to lure the reinforcements into an ambush “and Deciding the fortune of the day in the defiles thro’ which they must pass before they could gain possession of the strong Grounds.”[15]

Wayne ordered his troops to break off the action, but instead of obeying, they attacked the blockhouse. “Such was the Enthusiastic bravery of all ranks of Officers & men,” Wayne stated, “that the first Regiment no longer capable of restraint (rather than leave a post in their rear) rushed with Impetuosity over the Abbatis & advanced to the Stockades . . . altho’ they had no means of forcing an Entry—the contagion spread to the Second” regiment which joined the assault. The 10th Pennsylvania also attempted to attack, “as the same Gallant spirit pervaded the whole,” and Wayne noted that it was fortunate “that the Ground would not admit of the further advance of the 10th Regiment,” because it prevented their suffering as many casualties as the other two units. Only “by very great efforts of the Officers” of the 1st and 2nd Pennsylvania were those regiments “at last restrained.” Once the officers had gotten the infantry under control, the artillery was withdrawn for the anticipated clash with British reinforcements. The men in the infantry regiments collected their wounded and dead comrades and carried them off the field, “except three that lay dead under the stockades.”[16]

British accounts provided few details of the Loyalists’ defense. Clinton wrote that in the face of “a tremendous fire of musketry and cannon,” the “gallant band” of Loyalists “defended themselves with activity and spirit; and after sustaining the enemy’s fire for some hours,” they repulsed “an assault on their works.”[17] In his postwar Loyalist Claim, Ward remarked only that “the Post at Bull’s Ferry was attacked by General Wayne with a large Body Picked American Troops who after a very severe engagement were forced to retire.”[18]

While Wayne got his troops on the road and moving northward, Moylan’s dragoons drove their captured cattle toward New Bridge. An infantry detachment attacked the landing on the riverbank, below the blockhouse, and Wayne reported they “destroyed the Sloop & Wood boats” found there, capturing “a Capt. & Mate with two Sailers—some others were killed” as they tried to escape by swimming. The detachment “pushed forward to oppose the troops from Voluntines hill that we expected to land at the rear at New Bridge.” However, “in this project we were Disappointed, the enemy thought proper to remain in a less hostile position—than that of the Jersy shore,” Wayne lamented.[19]

On July 25, the Pennsylvania Packet newspaper published an account of the American operations that sought to portray those events in as favorable a light as possible. According to the Packet, the purpose of Wayne’s movement had been to collect and carry off “the cattle in Bergen County, New Jersey, which were exposed to the enemy.” Having completed that task, Wayne was returning to his camp when he “visited a block-house in the vicinity of Bergen town, built and garrisoned by a number of refugees to prevent the disagreeable necessity of being forced into the British seaservice.” The blockhouse proving to be invulnerable to artillery fire, the 1st and 2nd Pennsylvania regiments “were ordered to attempt it by assault.” They succeeded in “forcing their way through the abattis and pickets,” though “a retreat was indispensably necessary” after the attackers found there was “no other entrance into the block-house but a subterranean passage,” so narrow that it could only be traversed in single file.[20] Although the article contradicted much of the information in Wayne’s reports, it did display the imaginative talent of its author.

The Packet included one apparently factual detail that Wayne did not mention: that a Lieutenant Moody and six men were captured on their return from Sussex. The statement supports information provided by Clinton, also omitted by Wayne, that “the Exertions of the Refugees did not cease after having resisted so great a force. They followed the Enemy, seized their Stragglers and rescued from them the Cattle they were driving from the neighbouring district.” Clinton reported that six Loyalists were killed and fifteen wounded in the engagement, “the far greater part in the Blockhouse.” According to the Packet, American casualties were sixty-nine killed and wounded, in addition to the seven men captured.[21] In his official return, Wayne listed a total of sixty-four killed and wounded, making no mention of prisoners.[22]

Wayne was clearly stung by his failure to capture the blockhouse, telling Washington that “should my Conduct & that of the troops under my Command meet your Excellency’s Approbation—it will much Alleviate the pain I experience in not having it in my power to carry the Whole of the plan into Execution—which was only prevented by the most Malicious fortune.”[23] Shortly afterward, Wayne wrote to Pennsylvania’s chief executive, Joseph Reed, and claimed that his raid had probably thwarted Clinton’s plan to attack the French in Rhode Island. Wayne believed that his operation had delayed the British departure from New York, allowing the French to make preparations adequate to defeat any attack. Wayne added that he had written Reed “to put the quietus on rumors by his detractors that he had rushed headlong into a useless, wasteful skirmish merely to embellish his own military reputation and that the assault really was worthless from start to finish.” Reed responded that he did not believe that Wayne had acted improperly, nor would any sensible person doubt that Wayne had done his duty.[24]

For his part, Clinton did believe that his “preparations for this expedition” to Rhode Island “had caused a movement in Mr. Washington’s army, with a view, it is supposed of diverting me from my object or at least retarding its taking place.” These efforts, Clinton asserted, caused no disruption, as “the route I had chosen putting within my reach the quickest intelligence of his motions, I knew I could regulate mine according to them at a moment, and they of course suffered no interruption from them. None, however, appeared to have a serious tendency but one,” the attack at Bull’s Ferry, and there Clinton remarked that “the issue turned out exceedingly honorable to a small body of loyal refugees.” He praised the blockhouse’s defenders, declaring that “such rare and exalted bravery merited every encouragement in my power, and I did not fail to distinguish it at the time by suitable commendations and rewards, to which I had soon after the satisfaction to add the fullest approbation of their sovereign.”[25] Clinton was referring to a letter he sent to Germain on August 20 describing the action and lauding the Loyalists’ bravery. In his reply, Germain wrote that “the very extraordinary Instance of Courage shown by the seventy loyal Refugees in the Affair of Bulls Ferry . . . is a pleasing Proof of the Spirit and Resolution with which Men in their Circumstances will act against their Oppressors, and how great advantages the King’s Service may derive from employing those of approved Fidelity.” Germain added that he had informed George III of the Loyalists’ valor, and that the king was pleased with their “intrepid Behaviour.”[26]

Major John André left the official commentary on the action to others, preferring instead to commemorate the Loyalists’ success in verse. André’s poem, Cow-chace, in Three Cantos, may not have been a of literary masterpiece, but it was skillfully composed to ridicule Wayne and other American officers with an almost savage intensity. No opportunity for criticism was overlooked, no insult omitted. The poem opened with the following lines:

To drive the kine, one summer’s morn,/The TANNER took his way;/The calf shall rue that it unborn/The jumbling of that day.

And Wayne descending Steers shall know,/and tauntingly deride,/And call to mind in ev’ry low/The tanning of his hide.

Yet Bergen Cows still ruminate/Unconscious in the stall,/What mighty means were used to get/And lose them after all.[27]

The mentions of “tanner” and “tanning” were references to Wayne’s prewar occupation. André went on to describe how the Americans arrived at their objective, “All wond’rous proud in arms” and waited while Wayne spoke: “When Wayne, who thought he’d time enough,/Thus speechified the whole.” André then provided an imaginary oration from Wayne that included his intention to attack the “paltry Refugees,” “level” their blockhouse, “And deal a horrid slaughter;/We’ll drive the scoundrels to the devil,/And ravish wife and daughter.” Yet while the attack was underway, Wayne allegedly said that he would go and round up the cattle, implying that he wanted no part of the fight. Collecting cows, André had Wayne declare, was “The serious operation” while the battle with the Loyalists was “only demonstration.”[28]

In addition, André jabbed American Maj. Gen. William Alexander, who claimed to be a Scottish nobleman and preferred to be called Lord Stirling. It was a bizarre affectation for someone fighting to overthrow monarchical rule, and André wrote “Let none uncandidly infer,/That Stirlingwanted spunk,/The self-made Peer had sure been there,/But that the Peer was drunk.” Although there is no evidence to suggest that Major Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee participated in the operation, André could not resist the chance to lampoon him as well, writing that the battle at the blockhouse raged “Whilst valiant Lee, with courage wild,/Most bravely did oppose/The tears of woman and of child,/Who begg’d he’d leave the cows.” Wayne, according to André, did not even bother with the cattle roundup. Instead, he fell “a prey to female charms,/His soul took more delight in.” As a result, “SoRoman Anthony, they say,/Disgrac’d th’imperial banner,/And for a gipsy lost a day,/Like Anthonythe TANNER.”[29]

As “The mighty Lee” stood in his stirrups “And drove the terror-smitten cows,” the troops who had attacked the blockhouse came fleeing down the road in panic, running all the way to New Bridge. André claimed that Wayne had lost his horse, which carried the general’s “military speeches” and “corn-stalk whisky for his grog.” In the final stanza, intended as sarcasm but incredibly prophetic, André chided that “I tremble” if Wayne “Should ever catch the poet.”[30]

Wayne’s biographer Paul David Nelson observed that André’s poem was “widely read by both British and Americans, and General Wayne suffered not a few pangs of indignity” as a result. However, though it was not Wayne who captured him, on September 23 (ironically the same day that the last portion of Cow-chace was published), André was taken prisoner by American militia as he was returning from West Point; he had gone there to confer with Benedict Arnold regarding the latter’s plan to hand over that post to the British. André was hanged as a spy on October 2.[31]

Wayne’s reputation survived the defeat at Bull’s Ferry and the poetic insults André had hurled at him, and he continued to earn fame for his military exploits. His opponents, the defenders of the blockhouse, were largely forgotten. Captain Ward became a major and was awarded a pension by the British government after the war, and nearly twenty of his militiamen who had participated in the battle received land grants in Canada and settled there after the British evacuated New York.[32] Although the outcome of the engagement did not affect the future course of the war, the battle at Bull’s Ferry deserves attention as one of the most fascinating David-versus-Goliath-type incidents of the Revolution.

[1]Paul David Nelson, Anthony Wayne: Soldier of the Early Republic (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985), 108.

[2]Anthony Wayne to George Washington, July 19, 1780, www.founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-02573.

[3]Washington to Wayne, July 20, 1780, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-02587.

[4]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780, www.founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-02629.

[7]Nelson, Anthony Wayne, 109.

[8]Walter T. Dornfest, Military Loyalists of the American Revolution: Officers and Regiments, 1775-1783(Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2011), 351; H. H. Burleigh, “The Block House in Bergen Wood,” www.uelac.org/PDF/The-Block-House-in-Bergen-Wood.pdf.

[9]Henry Clinton, The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton’s Narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782, With an Appendix of Original Documents, William B. Willcox, ed. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1954), 200-201.

[10]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780.

[11]Quoted in Burleigh, “Block House.”

[12]Zebulon Pike to Wayne, July 21, 1780 (two letters), enclosures in Wayne to Washington, July 21, 1780, Founders Online, National Archives, www.founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-02606.

[13]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780.

[14]Wayne to Washington, July 21, 1780.

[15]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780.

[17]Clinton, American Rebellion, 201.

[18]Quoted in Burleigh, “Block House.”

[19]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780.

[20]Quoted in Burleigh, “Block House.”

[22]Wayne to Washington, July 22, 1780.

[24]Nelson, Anthony Wayne, 111.

[25]Clinton, American Rebellion, 200-201.

[26]Quoted in Burleigh, “Block House.”

[27]John André, Cow-chace, in Three Cantos, Published on Occasion of the Rebel General Wayne’s Attack of the Refugees Block-house on Hudson’s River, on Friday the 21stof July, 1780 (New York: James Rivington, 1780), 3.

4 Comments

Thank you for your informative and enlightening article. I had acquired an updated copy C.H Winfields 1904 reprint of his magazine article, The Blockouse by Bull’s Ferry. The latter was published 25 years prior. Your article greatly clarifies events. My SAR ancestor enlisted in Moylan’s regiment after service in the 5th VA and Morgan’s regiment. Now I see his cattle rustling played a role in Andre’s work.

Jim,

Thanks for the interesting article. I had not heard of this incident before, bu then again, my interests generally are north of NYC.

Anyway, by then, was not Andre the Adjutant General of the British Army and not just an aide-de-camp?

Thank you for the interesting article!

For more on the capture and subsequent escape of Tory Lieutenant James Moody, see my 2020 JAR article “Contingencies, Capture, and Spectacular Getaway: the Imprisonment and Escape of James Moody.” It’s nice to see more on the Bulls Ferry blockhouse and Wayne’s attack on it.

Dr. Piecuch,

Thank you so much for researching and writing this article. It is very sad that, to the casual reader, there is so much misinformation in printed, as well as on-line sources about this Battle. Charles Winchester wrote three accounts. While his earliest account, in History of Hudson County New Jersey (New York: Kennard & Hay) 1874 got the location of this blockhouse wrong, his 1880 much more detailed article “The Affair at Block-House Point” in Magazine of American History V.5, No. 3, p. 173 (as digitized by Google) was able to get the precise location thanks to access to an April 30, 1780 written order from British General Pattison, New York to Major Lumm at Paulus, Hook, to “…take post upon the Heights, half a Mile below Bull’s Ferry, upon the North River, in such manner as will most effectively cover a Body of Refugees under Col Cuyler, who are to tale Post and establish themselves, at the Place above mentioned this Night, in order to cut wood for the Army…”, which was discovered and apparently first published in 1875 in N.Y. Historical Society Collections. In 1904, William Abbatt published in book form, a posthumous account by Winfield, The Block-House By Bull’s Ferry. Todd Braisted, who will definitely forget more about Revolutionary War history than I’ll ever learn, in his seminal A Nest of Tories, was the first to research and publish the names of upwards of 138 Loyalists who fought at this Battle. I self-published 1780 Battle of the Block House of North Bergen, New Jersey in 2028 119 pages and updated same in 2021. There absolutely needs to be a marker placed at this battle site.

Fraternally,

SFC (R) Patrick R. Cullen, Jr.

NYARNG, Army Veteran

W.N.Y., NJ Town Historian