It is widely acknowledged that the military alliance between the United States and France, established in 1778, was responsible not only for a number of American victories over the British, but also for the end of the Revolutionary War. While much has been written about this topic as well as the events that occurred between 1777 and 1778, which led to the alliance, far less is known about the factors that took place in 1775 and 1776 that contributed to the initial need for the alliance, as well as the factors that culminated in the eventual signing of the alliance.

Background

Between June 5, 1775, when George Washington became commanding general of the Continental Army and the end of that year, the British and Americans had engaged in seventeen important battles, skirmishes, and naval confrontations, of which twelve were won by the Americans.[1] Although from a military perspective the Continental Army was a reasonably effective fighting force, the colonies not only had hoped to free themselves from England’s dominance either by winning the war or through negotiations, but also had hoped to become an effective trading partner with many European nations. With these dual objectives in mind, in the latter part of 1775, they began to court France, an acknowledged world power, for additional military support as well as for the political acceptance they needed to gain the trust required by these other nations.

Without some acknowledgement of their legitimacy, the colonies were merely rebels, traitors, and pirates; recognition [by France] would transform them from criminals to statesmen, diplomats, and privateers. Other European powers would quickly follow French recognition. It would afford the Americans opportunities for trade relations, loans, and alliances through Europe that were essential to securing and maintaining independence.[2]

In addition to these dual objectives, though, the immediate reason for pursuing France in 1775 was the introduction on November 20 of the Prohibitory Act by Lord North, an act which is said to have been an instrument tantamount to a declaration of war between Britain and its American colonies.[3] While John Adams felt that the Act “throws the thirteen Colonies out of the Royal Protection, levels all Distinctions and makes us independent in spite of all our supplications and Entreaties,” he also felt obliged to conclude his remarks by stating that, “it is very odd that Americans should hesitate at accepting such a gift.”[4] In short, although Adams firmly believed that now was the time for the colonies to declare independence, the problem he clearly recognized was that the mood in Congress in 1775 was simply not compatible with need to “accept such a gift.” As these events developed, the expansion of hostilities gradually prompted the colonies to seek French assistance, beginning with an unsuccessful attempt in 1775 to circumvent the British naval blockade.

The British Naval Blockade

“All American Vessels found on the Coast of Great Britain or Ireland are to be seized & confiscated on the first Day of January [1776]—all American Vessels sailing into or out of the ports of America after the first of March are to be seized & confiscated- all foreign Vessels trading to America after the first of June to be seized . . . All Captures made by British Ships of War or by the Officers of the Kings Troops in America [will be] adjudged by this Act to be lawful Prizes and as such Courts of Admiralty to proceed in their Condemnation.”

This British naval order stemmed from provisions near the end of the Prohibitory Act and was found in “Some Newspapers and private Letters . . . stowed away by a Passenger in the Bottom of a Barrel of Bread . . . which escaped Search.”[5] The information eventually was received by the Maryland Council of Safety in a letter dated February 27, 1776.

Though not mentioned by name in any of the Congressional minutes that took place following Lord North’s introduction of the Act, Congress must already have been aware of these provisions, since as early as January 6, 1776, it had also approved a resolution to compensate American seamen who took part in the capture of any British ships “as lawful prizes” of war.

That the Commander in chief [of any American naval vessels] have one twentieth part of the said allotted prize-money . . . [and that the] captain of any single ship have two twentieth parts for his share . . . that surgeons, chaplains, pursers, boatswains, gunners, carpenters, masters’ mates, and the secretary of the fleet, share together two twentieth parts and one half of one twentieth part divided amongst them equally . . . (and the rest of the ship’s company) at the time of the capture receive eight twentieths, and one half of a twentieth, be divided among them equally.[6]

Indeed, owing to this British “declaration of war,” the North Atlantic in 1776 had truly become a virtual highway for British military vessels. Between December 31, 1775, and December 31, 1776, 895 ships had sailed from England transporting British troops along with their provisions to the North American colonies.[7] In fact, to cope with this problem, as early as January, 1776, Congress had purchased eight ships and ordered thirteen others that “could carry as many as 120 guns and crews up to 1,000.”[8] In the case of any American ships destined to leave American ports, Congress had also issued messages for the ship owners to warn their captains “to take every possible precaution to avoid all British men of war and cutters on the voyage.”[9]

In view of what was obviously becoming a steadily worsening military and maritime situation, it is not surprising that as early as September 18, 1775, Congress had formed a committee known initially as the Secret Committee, the sole purpose of which was to establish overseas contracts for “the importation and delivery of quantities of gunpower . . . brass field pieces, six pounders . . . twenty thousand good plain double bridled musquet locks . . . and ten thousand strand of good arms.”[10]

The Evolution of the Secret Committee

Although the Secret Committee’s original mandate was solely to procure military supplies, shortly after it was established, and as a result of the blockade, its mandate was broadened to cope with what had become an extremely serious financial problem for many local merchants who were engaged in domestic as well as foreign trade. To help overcome this problem the committee’s name was changed to the Secret Committee on Trade because it was also asked to consider how best to establish trade connections on both sides of the Atlantic. As an example of domestic trade, on October 2 the Secret Committee introduced the following recommendation:

To encourage the internal Commerce of these Colonies, your Committee thinks Provision should be had to facilitate Land Carriage, and therefore are of the opinion that it should recommend by this Congress to the several provincial Conventions and Assembles, to put their Roads in good Repair, and particularly the great Roads that lead from Colony to Colony.[11]

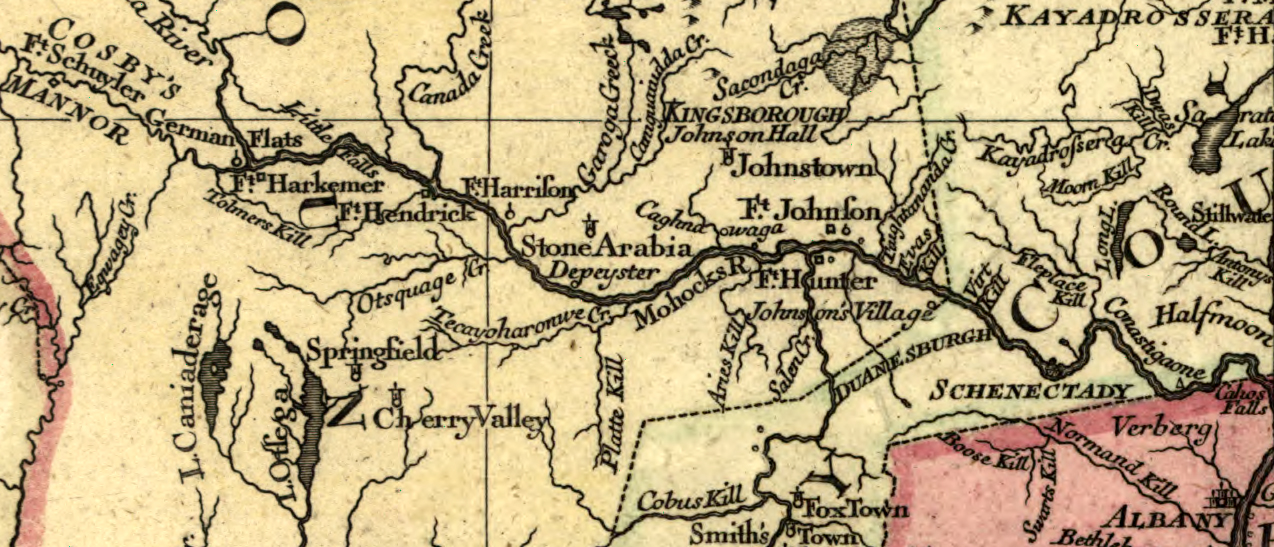

Next, the Secret Committee was asked to devise a plan “for carrying on a trade with the Indians, and the ways and means for procuring goods proper for that trade.”[12] Such action was considered essential to prevent the Indians from joining forces with the British as well as to maintain the Indian’s longstanding wish to remain neutral throughout the war.[13] Owing to this further increase in responsibility, the committee’s name then became the Secret Committee on Trade and Commerce.

In essence, and with this final role in mind, the overall mandate of the Secret Committee needed to satisfy three major goals: (1) obtain foreign military assistance, (2) establish foreign and domestic commercial trade connections, and (3) enhance Indian trade relations. To achieve these goals, all of which stemmed in one way or another from the Prohibitory Act, a nine-member panel was selected with Thomas Willing as chair. Since the focus of two of the three committee goals was on trade and commerce, it is not surprising that of this number, six of the committee members (John Alsop, Philip Livingston, Silas Deane, Samuel Ward, and John Langdon), along with the committee chair, were all highly successful merchants, many of whom also had developed considerable experience forming important overseas trading connections. Although Willing resigned shortly after the panel was formed, he was replaced by Robert Morris who was Willing’s partner in one of the largest and most successful overseas shipping companies in the colonies.

The first overture of the Secret Committee took place on December 12, 1775. During a meeting held in America with the French foreign minister, the comte de Vergennes, the committee was told that “France is well disposed to you; if she should give you aid, as she may, it will be on just and equitable terms. Make your proposals and I will present them.” The committee was also told not to move forward until Vergennes let them know when and how it would be best to proceed.[14] With these thoughts in mind the committee then began to develop plans to initiate talks not only with France but also with other European governments who might be interested in establishing military and trade relations with the united colonies.

Because of its highly sensitive mission, Congress had resolved that the business of the committee needed “to be conducted with as much secrecy as the nature of the service will possibly admit,” which meant that many of its records were destroyed.[15] For this reason, much of the following was distilled from the personal letters of the committee members who played a central role in the unfolding events: Morris and Deane. While Morris, as committee chair, remained in America and served as Deane’s major contact, Deane was selected to implement the committee’s overseas plans. Among the reasons given for Deane, he was well known to all of the other members of the committee, had many foreign contacts as the result of his highly successful commercial business in Connecticut, and, perhaps of even greater importance, Deane was the only committee member who was not an elected delegate to Congress.

On your arrival in France you will [appear] . . . in the Character of a Merchant, which we wish you continually to retain among the French in general, it being probable that the Court of France may not like it should it be known publicly, that any [congressional] Agent from the Colonies is in that Country [to conduct business].[16]

The first set of instructions Deane received appeared in a letter from Morris, dated February 19, 1776.

We deliver you herewith one part of a Contract made with the Secret Committee of Congress for exporting Produce of these Colonies to Europe & Importing from France Certain Articles suitable for the Indians . . . We [also] deliver to you herewith Sundry letters of introduction to respectable Houses in France which we hope will place you in the respectable light you deserve to appear & put you on a footing to purchase the Goods wanted on the very best terms . . . We think it prudent thus to divide the remittances that none of the Houses may know the Extent of your Commission but each of them will have orders to Account with you for the Amount of what comes into their hands for this purpose . . . The Vessel [we hired to deliver the goods] is on Monthly pay. Therefore, the sooner you dispatch her back the better & you will give this captain . . . suitable directions for approaching this Coast on their return [to avoid the blockade].[17]

The same letter also contained the following information, which indicates how purchasing arrangements were to be made.

That the sum of $200,000 in continental money now advanced and paid by the said Committee of Secrecy to the said John Alsop, Francis Lewis, Philip Livingston, Silas Deane and Robert Morris, shall be laid out by them in the produce of these Colonies and shipped on board proper vessels, to be by them chartered for that purpose, to some proper port or ports in Europe (Great Britain and British Isles excepted) and there disposed of on the best terms. . .(the proceeds from the sales of this produce should then be used to purchase) such goods, wares or merchandise as the Committee of Secrecy shall direct and shipped for the United Colonies to be landed in some convenient harbor or place within the same and notice thereof given as soon as conveniently may be to the said Committee of Secrecy.

Deane then received a second set of instructions from Morris that he was to implement when he arrived in Paris. To maintain the secrecy of his visit, he was told to inform those whom he would initially meet that he was only in Paris as a tourist (“it is scarce necessary to pretend any other business at Paris, than the gratifying of that Curiosity which draws Numbers thither yearly, merely to see so famous a City”) and that only when the time seemed most appropriate was he to request a meeting with the French foreign minister.

Initiating the Alliance

Deane was also told that upon meeting Vergennes, his message should be flattering, convincing, and contain no information that would allow anyone to know that he and Vergennes had previously met in America. The words in Morris’ letter were carefully crafted and designed to convey these exact points.

you had been dispatched by the Authority [of Congress] to apply to some European Power for a supply [of arms] . . . if we should [as there is great appearance we shall] come to a total Separation from Great Britain, France would be looked upon as the Power, whose Friendship it would be fittest for us to obtain & cultivate . . . it is likely that a great part of our Commerce will naturally fall to the Share of France, especially if she favors us in this Application as that will be a means of gaining & securing the friendship of the Colonies—And, that as our Trade rapidly increasing with our Increase of People & in a greater proportion, her part of it will be extremely valuable . . . That the supply we at present want is Clothing & Arms for 25,000 Men, with a suitable Quantity of Ammunition & 100 field pieces . . . That we mean to pay for the same by Remittances to France, Spain, Portugal & the French Islands, as soon as our Navigation can be protected by ourselves or Friends.[18]

The last set of instructions to Deane prior to his departure also dealt with arrangements that had been made for his passage from the colonies to France. Although scheduled to leave Philadelphia on March 8, due to many unforeseen delays, Deane finally set sail on May 3 and arrived at Bordeaux on June 6.[19]

Once in France Deane received a further set of instructions from Morris dated July 8, 1776. It was only at this point that Deane was able to make clear to Vergennes, that to satisfy a major condition as stipulated by France for receiving French military aid, the united colonies had finally broken away from Britain through the ratification of the Declaration of Independence and therefore was now able to negotiate on its own terms with all foreign nations.

With this [letter] you will receive the Declaration of Congress for a final separation from Great Britain . . . You will immediately communicate the piece to the Court of France, and send copies of it to the other Courts of Europe. It may be well also to procure a good translation of it into French, and get it published in the gazettes. It is probable that, in a few days, instruction will be formed in Congress directing you to sound the Court of France on the subject of mutual commerce between her and these States. It is expected you will send the vessel back as soon as possible with the fullest intelligence of the state of affairs, and of everything that may affect the interest of the United States. And we desire that she may be armed and prepared for defense in the return.[20]

On October 1 Morris wrote again, but this time he informed Deane that the committee had received nothing further from him since his departure at the beginning of May. Throughout the letter Morris expressed his considerable anguish over this lack of communication coupled with his concern over this lengthy passage of time.

It would be very agreeable and useful to hear from you just now in order to form more certain the designs of the French Court respecting us and our Contest especially as we learn by various ways they [the British] are fitting out a considerable Squadron . . . they may now strike at New York. Twenty Sail of the line would take the whole Fleet there consisting of between 4 & 500 Sail of Men of War, Transports, Stores, Ships, and prizes . . . alas we fear the Court of France will let slip the glorious opportunity and go to war by halves as we have done. We say go to war because we are of the opinion they must take part in the war sooner or later and the longer they are about it, the worse terms will they come in upon . . . The Fleet under Ld. Howe you know is vastly Superior to anything we have in the Navy way; consequently wherever Ships can move they must command; therefore it was long foreseen that we could not hold either Long Island or New York.[21]

Adding to his concerns, in an earlier letter Morris had also described to Deane the devastating impact that the blockade itself was having on all colonial commercial shipping.

I have bought a considerable quantity of Tobacco but cannot get suitable Vessels to carry it. You cannot conceive of the many disappointments we have met in this respect . . . So many of the American Ships have been taken, lost, sold, [or] employed abroad [as the result of the blockade] that they are now very scarce in every part of the Continent which I consider a great misfortune, for ship building does not go on as formerly.[22]

In addition to the blockade, and contrary to the previous year, of the twelve battles and skirmishes waged between the British and the American forces between August 27 and mid-December 1776, the British were victorious in all but two and in a number of these, the American losses, in contrast to the British, were often substantial. For example, on August 27 the British defeated Washington at the Battle of Brooklyn. Whereas the British suffered 337 wounded or missing and 63 killed, the Americans suffered 1,079 wounded or missing and 970 killed. Then on December 1, under Washington’s command, the Americans arrived at the Delaware River, crossed into Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and shortly thereafter it was anticipated by the Americans that Philadelphia would soon be attacked. In view of these events it is fitting that this period has been referred to as “one of the lowest points of the war for the patriots.”[23]

On October 23, to prevent an anticipated invasion of New York, Morris further requested Dean “to procure Eight Line of Battle Ships either by Hire or purchase. We hope you will meet immediate success in this application and that you may be able to influence the Courts of France & Spain to send a large Fleet at their own Expense to Act in Concert with these Ships.” Although at first glance this last request by Morris may seem surprising because it called upon France as well as Spain to now engage in an act of war against Britain, the request was clearly in line with Article 4 in a September 24, 1776, congressionally-approved “Plan for a Treaty” to be negotiated by the Americans with France. It is also the case that despite the very large number of articles in the plan, it was only this article, along with Article 3 that the treaty negotiators were informed “must be insisted upon” during the course of negotiations.[24] In short, because the plan was approved by Congress in September 1776 and because France’s initial offer of assistance to the colonies in their dispute with England took place in December 1775, Congress must have expected France to become active in the colonies’ military engagements once the Declaration of Independence had been ratified.

As the events outlined above steadily unfolded, it is not surprising that the members of Congress found themselves in an increasingly desperate situation. With no other help to call upon, it is also perhaps not surprising that on December 11 Congress approved the following Resolve.

That it be recommended to all the United States, as soon as possible, to appoint a day of solemn fasting and humiliation; to implore of Almighty God the forgiveness of the many sins prevailing among all [military] ranks, and to beg the countenance and assistance of his Providence in the prosecution of the present just and necessary war. . . . It is left to each state to issue out proclamations fixing the days that appear most proper within their several bounds.

To ensure that this message was clearly understood by all concerned, the Resolve also called upon the members of the military itself, including the military hierarchy, to act in accordance with the Almighty’s wishes.

all members of the United States and particularly the officers civil and military under them, [to practice] the exercise of repentance and reformation; and further, require of them the strict observation of the articles of war, and particularly, that part of the said articles, which forbids profane swearing, and all immorality.[25]

Finally, on December 30, 1776, Congress issued its last attempt of the year to avoid total defeat by providing France with the following enticement to come to its aid: “should the Independence of America be supported [by France], Great Britain . . . would at once be deprived of one third of her power and Commerce; and that this in a great Measure would be added to the Kingdom of France.” In the event this enticement failed to achieve its objective, Congress then also threatened France with the consequences that would result if it did not immediately enter the war on behalf of the Americans colonies.

in Case Great Britain should succeed against America, a military Government will be established here [in America] and the Americans already trained to arms, will, however unwilling, be forced into the Service of his Britannic Majesty, whereby his [Majesty’s] power will be greatly augmented and may hereafter be employed [to take over] the French and Spanish islands in the West Indies.[26]

Unfortunately, given the prevailing international climate in 1776 as dictated by Britain and Spain, France elected to offer only secret financial and limited material aid in support of the colonies, and not the type of aid being requested by Congress. Therefore, France refused to go beyond what it felt, at that time, was most appropriate in satisfying its own best interests and chose to remain officially out of the war.[27]

Culminating the Alliance

The situation described above suddenly changed in the fall of 1777. On October 31, Congress sent a letter with the following information to its delegates in Paris.

We have the pleasure to enclose the capitulation, by which General Burgoyne and his Whole army surrendered themselves [at Saratoga as] prisoners of war . . . We rely on your wisdom and care to make the best and most immediate use of this intelligence to depress our enemies and produce essential aid to our cause in Europe.[28]

With this information in mind, the American delegates in France who “were attempting to play upon fears [told the French representatives] that an accommodation between Great Britain and the revolting colonies was [now] possible and even imminent.”[29] The significance of these two factors and the anxiety they must have generated among the French was fully captured in the following words by Bemis.[30]

The fear that the British Ministry, staggering under the blow of Saratoga, was about to offer to the Colonies peace terms generous but short of independence had an immediate effect in France. Anxious lest such terms might be accepted by the war-weary Americans . . . the French Ministry felt that if something were not done quickly, the long-awaited chance, at last at hand, for sundering the British Empire might pass and be gone forever.

The Treaty of Amity and Commerce along with the Treaty of Alliance, both of which together are often referred to as the French Alliance, were finally signed on February 6, 1778. A question that still remained, though, was how would the Kingdom of France cover the costs associated with supplying all the military aid America needed to win the war? Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot, France’s Minister of Finance, repeatedly warned the King that “the first gunshot will drive the state to bankruptcy.”[31] The answer can be found in the following material.

On July 16, 1782, Benjamin Franklin, Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States of North America, agreed and certified that the sums advanced by His Majesty to the Congress of the United States . . . under the title of a loan, in the years 1778, 1779, 1780, 1781 and the present 1782, [to repay] the sum of eighteen million livers, money of France . . . on the 1st of January, 1788, at the house of the Grand Banker at Paris . . . with interest at five per cent per annum.[32]

To prevent a French financial catastrophe it appears that Congress had authorized Franklin to underwrite a series of French loans to cover the cost of the French military help it needed to achieve victory over Great Britain. While on the surface it would seem that France was taking a considerable risk in agreeing to this procedure, the reality of the situation suggests that it had no other choice. If the United States had lost the war, France’s fears of a British takeover of its territory could very well have been realized, whereas, if the United States won, the loans would have been repaid and France would have been able to maintain its position as a European power. Although the agreement was indeed a gamble, it was a gamble that France was simply forced to take.

Despite the fact that the Alliance had been signed on February 6, 1778, it is equally important to note that, due to the naval blockade, Congress had received no further word on this matter from its overseas delegates since May 1777. As a result, Congress was faced with an additional problem as expressed on April 30, 1778, in a letter to its Paris representatives.

We have read a letter written by a friend dated Feb. 13, 1778, in which we are told that “you had concluded a Treaty with France and Spain which was on the Water towards us.” Imagine how solicitous we are to know the truth of this before we receive any proposals from Britain in consequence of the scheme in Ld. North’s speech and the two Draughts of Bills now sent to you.[33]

The “proposals” in this letter referred to the terms for reconciliation that Lord North had authorized in March 1778 for the Carlisle Peace Commission to use as a means for negotiating an end to the war with America. The difficulty Congress now faced, however, stemmed not only from Lord North’s proposals, but also from two Congressional counterproposals drafted by Samuel Huntington and by Henry Drayton, respectively.[34] Henry Laurens, who at the time was president of the Congress, was extremely troubled over this issue and expressed his personal concern in a letter to his son.

Some of our people here have been exceedingly desirous of throwing abroad in addition to the Resolutions an intimation of the willingness of Americans to treat with G Britain upon terms not inconsistent with the Independence of these States or with Treaties with foreign powers. I am averse. We have made an excellent move on the Table—rest until we see or learn the motions on the other side—the whole World must know we are disposed to treat of Peace & to conclude one upon honorable terms. To Publish [anything on this matter at present is] therefor unnecessary [and] it would be dangerous to Act, encourage our Enemies & alarm our friends.[35]

Stated more succinctly, Laurens’ concern stemmed from the possibility of reaching too hasty a conclusion without a full understanding of the overall ramifications in the different sets of proposals. To behave in this manner would simply not have been in the best interests of the United States.

Although Congress did debate the matter at the end of April, as the result of the fact that Silas Deane had arrived at York on May 2, the debate only lasted two days.[36] With official versions of the Treaty of Alliance and the Treaty of Amity and Commerce now in hand, Deane was able to show that the French Alliance had indeed been signed in February, which meant that closure had been achieved and no further debate was required. For the members of Congress, their long sought-after goal of French military aid could now finally be considered as secure.

[1]Harry Karapalides, Dates of the American Revolution (Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press, 1998), 36-52.

[2]Joel R. Paul, Unlikely Allies (New York: Riverhead Books, 2009), 130.

[3]Thomas Fleming,1776 Year of Illusions (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1975), 78.

[4]David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 14.

[5]Letters of Delegates to Congress, 3:308-309.

[6]Journals of the Continental Congress, 4:36-37.

[7]David Syrett, Shipping and the American War 1775-83 (London: The Athlone Press, 1970), 249.

[8]James K. Martin and Mark E. Lender, A Respectable Army: The Military Origins of the Republic, 1763-1789 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2006), 144.

[9]Journals of the Continental Congress, 4: 108.

[13]Milton C. Van Vlack, Silas Deane, Revolutionary War Diplomat and Politician (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2013), 77-78; Barbara A. Mann, George Washington’s War on Native America (Westport, CN: Praeger, 2005), 10.

[14]George Bancroft, History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, Vol. 8 (Boston, MA: Little Brown and Co, 1853), 216.

[15]Journals of the Continental Congress, 2:254.

[16]Letters of the Delegates to Congress, 3:321.

[23]Karapalides, Dates of the American Revolution, 75.

[24]Journals of the Continental Congress, 5:769, 814.

[27]James Pritchard, “French strategy and the American Revolution: A reappraisal,” Naval War College Review, Vol 47, Issue 4 (1994), 87-89.

[28]Letters of the Delegates to Congress, 1777, 215-216.

[29]Gerald S. Brown, The American Secretary (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1963), 151.

[30]Samuel F. Bemis, The Diplomacy of the American Revolution (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press,1965), 60.

[31]Richard J. Werther, “Opposing the Franco-American Alliance: the Case of Anne-Robert Jacques Turgot,” allthingsliberty.com/2020/06/opposing-the-franco-american-alliance-the-case-of-anne-robert-jacques-turgot/.

[32]Contract between the King and the Thirteen United States of North America, signed at Versailles July 16, 1782,” avalon.law.yale.edu/18th century/fr-1782.asp.

2 Comments

Nicely Done. Am especially interested in the resource books listed in your footnotes as several are new to me! Am on my way to the library !!

Thanks for all you do!

On a side note, Thomas Paine got caught up in the secret negotiations between Congress and the French. He was appointed Secretary to the Committee on Foreign Affairs in 1777 by the Continental Congress, where, of course, he saw plenty of secret correspondence. (Some Paineites call Paine the first secretary of state). Increasingly suspicious that Deane was engaged in profiteering during his time negotiating in France, Paine accused him publicly in a couple of newspaper articles, which of course let the cat out of the bag about the ongoing secret negotiations. Infuriating both the Congress and France, Paine was dismissed from his official role in 1799. But in early 1781, Paine accompanied John Laurens as his unofficial secretary, at Lauren’s expense, on his trip to France to seek financial support for the war and returned with him to Boston with the desperately needed assistance.