“Permit me to thank you, in the most affectionate manner, for the kind wishes you have so happily expressed for me and the partner of all my domestic enjoyments. Be assured, we can never forget our friend at Morven.”

George Washington[1]

To whom was George Washington writing and why did he offer, “in the most affectionate manner,” a thank you? A remarkable woman of colonial and revolutionary America: a published poet, patriot, as well as devoted wife and mother.

Annis Boudinot Stockton’s paternal ancestors were French Huguenots who left France after Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes. The family first went to England, then her grandfather Elias II emigrated to New York City, where her father was born in 1701. Elias III became an apprenticed silversmith and upon the completion of his apprenticeship went to the island of Antigua. In 1733 he married Catherine Williams, the daughter of a Welsh plantation owner. Due to unrest on the island they moved to Philadelphia, where Annis was born on July 1, 1736.[2] Annis had four brothers: John, Elias IV, Elisha, and Lewis, and one sister, Mary.[3]

In 1753, Elias III bought a share in a copper mine in the area around New Brunswick, New Jersey, and moved the family there. Then after a brief stay in Rocky Hill, he bought a tavern in Princeton. This move was to have a major impact on Annis—she became a friend of Esther Edwards Burr. Esther, the daughter of prominent minister Jonathan Edwards, married Aaron Burr, Sr. in 1752. He became the second President of the College of New Jersey, a New Light Presbyterian School that had relocated to Princeton.[4]

It has been stated that Esther, sixteen years the junior of her husband, was somewhat lonely due to the frequent absences of her husband, often away on college business.[5] The book Morven: Memory, Myth, and Reality states: “Esther was lonely in Princeton—Annis Boudinot, whose sweet nature and talents appealed to her, became one of her few friends.”[6] Esther wrote a letter to a friend in Boston, Sarah Prince, on December 10, 1756, in which she wrote the following about Annis:

But I must tell you what for neighbours I have—the Nighest is a young Lady that lately moved from Brunsweck, a pretty discreet well behaved girl. She has good sense and can talk very handsomely on almost any subject, I hope a good Girl two—I will send you some peices of poetry of her own composing that in my opinion shew some genious that way that if properly cultivated might be able to make no mean figure.[7]

Esther also referred to Annis as her “poetis.”[8]

Annis, through the auspices of Esther Burr, was introduced into Princeton’s social and intellectual elite—among them the Stockton family, descendants of one of the original settlers in the area. Most likely Annis formed a friendship with John and Abigail Stockton’s three daughters who were close to her in age; more importantly, she formed a bond with the oldest son, Richard. Richard Stockton, six years Annis’s senior, had been in the first graduating class of the College of New Jersey in 1748 when it was located in Newark. He remained in Newark where he studied law under a prominent lawyer, David Ogden. Upon being admitted to the Bar in 1754, he began a very successful law practice. When Richard had passed the Bar, his father conveyed to him, for the sum of £5, one hundred and fifty acres of land on the north side of the King’s Highway, on which Annis and Richard would build their Georgian style mansion, Morven.[9]

The friendship between Annis and Richard developed into a romantic relationship and eventual marriage.[10] The two came from different family backgrounds, Annis being the daughter of a silversmith and tavern keeper, while Richard was a scion of wealthy landowning gentry and legal professionals, but the marriage was a love match: “Their surviving letters and Annis’s poetry are full of expressions of affection and concern for each other. They shared interests in books, poetry, literary friends, horticulture, and politics.”[11]

Richard began to take an interest in politics in 1765 when he wrote and spoke about his opposition to the Stamp Act. Then in 1766, he decided to take a trip to the British Isles. He wanted Annis to accompany him but because there were four children between the ages of two and seven, felt she had to remain home to care for them. During his trip, Richard met several influential personages and gave a speech to King George as a representative of the College of New Jersey thanking him for the repeal of the Stamp Act.[12] The social highlight of his trip was attending the Queen’s Birthday Ball. Also, on business for the College, with the help of Benjamin Rush who was studying medicine at the University of Edinburgh, they convinced Dr. John Witherspoon, a prominent Presbyterian minister, to come to Princeton to be President of the College.[13] One result of the notoriety that Richard achieved during his time in Britain was that in 1768, Benjamin Franklin’s son William, Royal Governor of New Jersey, named Richard to the Governor’s Council; then in 1774 Governor Franklin appointed him to the New Jersey Supreme Court.[14] This seemingly idyllic life of the Stocktons was to come to an end in 1775 with the onset of the War of Independence.

Richard Stockton, a political moderate, eventually sided with the independence-minded Whigs and accepted an appointment to the Continental Congress in June 1776. He became one of the five Signers of the Declaration of Independence from New Jersey. For the remainder of the summer and into the autumn, things did not go well for the Patriots in the war. On November 29, 1776, with the British army approaching Princeton, both Stockton and Dr. Witherspoon decided it was prudent to leave. It was reported that Annis buried three boxes of silver and valuables. She also went to the College, where she collected and then hid the papers of the Whig Debating Society.[15] Witherspoon went with Gen. George Washington’s army across the Delaware, while Stockton elected to take his family east to Freehold, New Jersey to the home of John Covenhoven.[16] Within two days, he was taken by local Loyalists and turned over to the British, then imprisoned in the Provost Jail in New York City. Richard Stockton is reportedly the only civilian signer of the Declaration arrested by the British.[17]

After a few weeks being held in this notorious jail and the dismal prospects for the Patriot cause, he signed the Oath of Pardon offered by British peace commissioners.[18] Following his signing the oath, Richard Stockton was released and he returned to Princeton. Life for Richard and Annis would never be the same as before the war. Their home, Morven, had been taken over by the British during the month they occupied Princeton and sustained severe damage that their son-in-law Benjamin Rush estimated at around £5,000.[19]

Having accepted British amnesty, Richard’s reputation was tarnished in the eyes of a number of Patriots. He resigned from Congress and resumed his law practice, but due to the terms of his pardon his clients were only those who were either not active in the cause of independence or were Loyalists. In December 1777, he took New Jersey’s Oath of Abjuration and Allegiance, required for those who had taken the British amnesty if they wanted to avoid arrest or the confiscation of their property.[20] Sadly, by the end of 1778, it became apparent that Richard had cancer of the lip. He had two surgeries to remove the malignancy, but with no success—Richard Stockton died on February 28, 1781.[21]

Annis was forty-five years old when she became a widow. She continued to mourn her husband for the rest of her life, mainly expressing her grief in her poetry.[22] In his will, Richard left Annis the whole of his “real and personal property” during the time of her widowhood, that is, until she died or remarried.[23] An interesting provision in his will stated that he left it up to Annis if she wanted to free the slaves they had. There is no indication that she did; in the 1790 tax roll there were three male slaves listed for Morven.[24]

Annis wrote to her brother Elias, “but though a female, I was born a Patriot, and I can’t help it if I could.”[25] The first example of her expressing her sentiments as a Patriot came in a poem: “On hearing that General Warren was killed on Bunker Hill, on the 17th of June 1775.”[26] Evidence that George Washington knew of Annis came when on February 27, 1779, he wrote to her brother, Elias Boudinot IV, the Continental Army’s first Commissary General of Prisoners:

I find myself extremely flattered by the strain of sentiment in your Sisters composition — But request it as a favor of you to present my best respects to her, andassure her, that however, I may feel inferior to the praize, she must suffer me to admire & preserve it as a mark of her genius tho’ not of my merits.[27]

It has been postulated that most likely he referred to her poem, “Addressed to General Washington in the year 1777 after the battles of Trenton and Princeton.” Annis had not sent it to Washington nor had it published, rather, it had been enclosed in a letter from Elias Boudinot to Washington.[28]

Annis’s first face-to-face meeting with Washington came on August 29, 1781, when he and General Rochambeau dined at Morven on their way to Yorktown. In a letter to her brother Elias dated October 23, 1781, Annis described her joy at meeting Washington and the victory at Yorktown:

I am sure for my part, since the day General Washington went from this house, and I guessed the Enterprise, I have had it so much at heart, that I have not forgot it day nor night, and so I will have pleasure in viewing it as the answer of my prayers, and if we women cannot fight for our beloved Country, we can pray for it, and you know the widow’s mite was accepted.[29]

Later she wrote a pastoral poem on the same topic titled “Lucinda and Aminta, a Pastoral, on the Capture of Lord Cornwallis and the British Army, by General Washington.”[30] On July 22, 1782, George Washington acknowledged an appreciation of her work when he wrote to Annis:

Madam: Your favor of the 17th, conveying to me your Pastoral on the subject of Lord Cornwallis’s Capture has given great satisfaction.

Had you known the pleasure that it would have communicated, I flatter myself your diffidence would not have delayed it to this time.

Amidst all the complimts which have been made on this occasion, be assured Madam, that the agreeable manner, and the very pleasing Sentiments in which yours is conveyed, have affected my Mind with the most lively sensation of Joy and satisfaction.

This Address from a person of your refined taste, and elegance of expression, affords a pleasure beyond my powers of utterance; and I have only to lament, that the Hero of you Pastoral, is not more deserving of your Pen; but the circumstance, shall be placed among the happiest events of my life.[31]

The next time that Annis Stockton and George Washington met in person was in 1783 when Congress fled Philadelphia and resumed meeting in Princeton.

In July 1781 Annis’s brother Elias Boudinot IV was elected to Congress by the New Jersey Legislature. On November 4, 1782, he was elected President of the United States Congress Assembled, making him the de facto Chief Executive of the United States. A critical decision he took came on June 21, 1783, when about three hundred Continental soldiers, disgruntled over the non-payment of past wages, threatened Congress in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania’s President John Dickinson refused to provide militia protection, so Boudinot recommended Congress adjourn and reassemble in Princeton, where they convened at Nassau Hall on July 2, 1783. They remained in Princeton until November.[32]

While they were meeting in Princeton, Congress invited General Washington to come and consult with them; he was in Newburgh, New York, with a remnant of the Continental Army. Washington and his wife Martha, three aides-de-camp, a contingent of the Life Guards, plus servants arrived at the home of Mrs. Margaret Berrien, Rockingham, in Rocky Hill, New Jersey, about four miles from Princeton.[33] He remained at this, his last military headquarters, until November. Although there is no record of it, most likely he and Martha had been hosted by Annis at Morven.

On August 26, 1783, Washington gave an address to Congress. It was reported Annis attended the event and a few days later, on August 28, 1783, she composed a poem of praise and sent it to Washington. In this poem, Annis began: “With all thy Countries Blessings on thy head—And all the glory that Encircles Man, Thy martial fame to distant nations spread,” and continued to list several honors bestowed on him. She ended the poem, “One thought of Jersey Enters in your mind Forget not her: on morvens humble glade Who feels for you a friendship most refin’d. Emelia.”[34] Annis must have wondered if she overstepped her bounds with her effusive praise about Washington’s achievements; on September 1, 1783, she sent a note to Washington asking: “Once more pardon the Effusions of Gratitude and Esteem, or Command the Muse no more to trouble you, for she Can not be restrain’d Even by timidity.”[35]

The next day Washington, in what seems a playful mood, replied to Annis’s poem and note. He began: “You apply to me, My dear Madam, for absolution as tho’ I was your father Confessor; and as tho’ you had committed a crime, great in itself, yet of the venial class.” He went on to flatter her for her poetry and invited her to dine with him “next Thursday,” “and go thro’ the proper course of penetence which shall be prescribed.” He concluded the letter, “Be assured we can never forget our friend at Morven; and that I am, My dear Madam, with every sentiment of friendship & esteem Your Most Obedt & obliged Servt Go: Washington.”[36] Of this letter from Washington, historian William Baker stated: “His reply in acknowledgement, dated Rocky Hill, September 2, 1783, is thought to be the most sprightly effusion of his pen.”[37]

Not feeling well, Martha left Rockingham at the end of October. General Washington left Rocky Hill and arrived at West Point on November 14. He then entered New York City after the British left on the 25th and on December 4, 1783, gave a farewell to Continental officers at Fraunces Tavern.[38] Making his way to Annapolis, where Congress was meeting, on December 23, 1783 he resigned as commander-in-chief and returned to Mount Vernon as a private citizen.

While these events were taking place, Annis composed a second part to her Pastoral that continued the dialogue between her characters Lucinda and Aminta: “Peace: A pastoral dialogue part the second.”[39] It was sent to Mount Vernon on January 4, 1784 but due to bad weather Washington didn’t receive it until February 10, 1784. On February 18 he sent Annis a letter commenting on the new Pastoral and commending her work:

I cannot, however, from motives of false delicacy (because I happen to be the principal character in your Pastoral) withhold my encomiums on the performance — for I think the easy, simple, and beautiful strains with which the dialogue is supported, does great justice to your genius.[40]

Washington concluded the letter: “Mrs Washington, equally sensible with myself, of the honor you have done her, joins me in most affectionate compliments to yourself, the young Ladies & Gentlemen of your family.” This was the last correspondence between Annis and George Washington until 1787.

The retired Commander-in-Chief returned to public service when he attended the convention to revise the Articles of Confederation in Philadelphia (May—September 1787) and was elected President of the Convention. On May 26, 1787, Annis sent Washington a poem titled “Epistle to George Washington.”[41] He replied on June 30, 1787, that he was sorry to take so long to reply but his duties at the Convention kept him busy:

I have to entreat that you will ascribe my silence to any cause rather than to a want of respect or friendship for you, the truth really is — that what with my attendance in Convention — morning business, receiving, and returning visits — and Dining late with the numberless &ca — which are not to be avoided in so large a City as Philadelphia, I have Scarcely a moment in which I can enjoy the pleasures which result from the recognition on the many instances of your attention to me or to express a due sense of them.[42]

On August 31, 1788, Washington sent Mrs. Stockton a letter expressing his feelings about the adoption of the new United States Constitution. He attributed it adoption to “Providence,”and also praised the role of women in the birth of the United States:

Nor would I rob the fairer Sex of their share in the glory of a revolution so honorable to human nature, for, indeed, I think you Ladies are in the number of the best Patriots America can boast.[43]

The Electoral College met on February 4, 1789 to vote for the President of the United States, casting their votes for the obvious choice, George Washington, with Congress certifying the results on April 6.

The next time Annis wrote to Washington was on March 13, 1789, when she sent him a letter and enclosed a poem on the anticipation of him becoming President; she began the letter:

Will the most revered and most respected of men, Suffer me to pour into his bosom the congratulations with which I felicitate my self on the happy prospects before us. I well know that there is nothing but the love of glory, and the enthusiasm of virtue, that is capable of animating a mind like yours — nothing but the sacred priviledge of serving your Country, and despensing happiness to millions, Could induce you to leave the calm delights of domestic ease and comfort.[44]

Annis went on to note that she was afraid that this would be their last correspondence:

But this is the only time I have ever written to General Washington, that I have felt a pensiveness amounting almost to regret at the thought that it is a kind of farewell letter as I must not presume to indulge my self by intruding on your time and patience, when you are surrounded with publick business therefore I was determined to answer your last most acceptable letter before you left Virginia.[45]

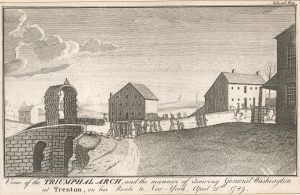

Washington sent a reply from Mount Vernon thanking her for her “polite letter and elegant poem.”[46] The culminating event in the interaction between Annis Stockton and George Washington came on April 21, 1789, when he passed through Trenton on his way to New York City for his Inauguration.

A triumphal arch was raised above the bridge over the Assunpink Creek, a crucial site of the Second Battle of Trenton fought on January 2, 1777, under which Washington passed. A banner on the arch proclaimed: “The Defender of the Mothers will also Defend the Daughters.” As he approached the bridge, a group of young ladies and matrons including Annis sang a song of praise.[47]

On May 1, 1789, she sent her last letter and poem to Washington. In the letter she stated:

Can the muse, can the friend forbear! (for oh I must Call thee friend, great as thou art) to pay the poor tribute she is capable off, when she is so interested in the universal Congratulation — I thought I Could testify my Joy when I saw you — but words were vain, and my heart was so filled with respect, love, and gratitude, that I Could not utter an Idea.[48]

Three days later, Washington sent Annis a thank you and his last correspondence with her:

Dear Madam,

I can only acknowledge with thankfulness the receipt of your repeated favors — were I Master of my own time, nothing could give me greater pleasure than to have frequent occasions of assuring you, more at large, with how great esteem and consideration, I am dear Madam, Your most obedient and most humble Servant, G. Washington[49]

Annis continued as the Dowager of Morven. Her eldest son Richard married Mary Field in 1788 and Annis turned the property over to him. The house was renovated and an east wing added that was mostly used by his mother and unmarried sisters. For the next nine years Annis lived off and on at Morven, spending time in town and visiting with the Rushes in Philadelphia. In 1797 an incident occurred between her and her daughter-in-law that resulted in her leaving Morven for good.[50] First, she went to live with her daughter Julia in Philadelphia. In 1798, on a visit to her youngest daughter Abigail who had married Robert Field (Mary’s brother) at their beautiful home, White Hill, along the Delaware River in Burlington County, she decided to reside with them. It was there that the sixty-five-year-old Annis Boudinot Stockton died on February 6, 1801. Her remains were taken to Philadelphia and buried in the Christ Church Cemetery.

So how does one sum up the life, poetry, and impact of this remarkable woman, the Muse of Morven,and her relationship to George Washington? One writer states the following about her poetry:

Annis Boudinot Stockton was one of the most prolific and widely published women writers in 18th Century America. Her poems in the English Neoclassical style remain the best known of her 120 works, which also include a play and numerous articles written for the leading newspapers and magazines of her day.[51]

The best description of Annis Boudinot Stockton’s poetry is from Carla Mulford, who edited all her known poems:

In keeping with her elite culture and her conservative social attitudes, Annis Stockton wrote and published poetry representing the “high” culture of eighteenth-century America. As mentioned earlier, she chose the most frequently used genres of her day—odes, elegies, epitaphs, epithalamia, sonnets, hymns—and she often chose the “visionary” or pastoral mode.[52]

How did General Washington regard Mrs. Stockton’s poems about him? According to L. H. Butterfield:

Of all subjects for patriotic eulogy Mrs. Stockton’s favorites, however, were General Washington and his victories. He was a family friend and several times a visitor at Morven. Poetry made him slightly uncomfortable, but he responded to Annis Stockton’s tributes in several gallant letters.[53]

It seems to me in the story of the Poet and the General we have a case of idol worship by a by a middle-aged, talented, Patriotic woman (might we even call her a “groupie”?) for her hero of the American Revolution. As for the “General” whom we usually regard as being somber and having a stoic personality, it seems he was delighted in her praise, sending thank you letters to her for her works about him in what seems to be in a playful, even flirtatious, manner.

[1]George Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, September 2, 1783,”founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11784.

[2]In some biographies it is stated that she was born in Darby, Pennsylvania, today in Delaware County south of Philadelphia.

[3]For some reason, in Boudinot Genealogies, Lewis is not reported. An example is found in the New Jersey Historical Society’s Manuscript Number 633 about Elisha who is described as “the youngest child of Catherine and Elias.” In the papers of Benjamin Franklin, it notes Lewis was born in Princeton in 1753; he is mentioned as presenting a letter to Benjamin Franklin. See Lewis Boudinot to Benjamin Franklin, September 29, 1783,” founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-41-02-0031.

[4]The College of New Jersey moved from Newark to Princeton in 1756.

[5]The Burrs had two children, a daughter Sally and a son Aaron, Jr.

[6]Constance M. Greiff, Wanda S. Gunning, Morven: Memory, Myth and Reality (Princeton: Historic Morven, Inc. 2004), 27.

[7]Esther Edwards Burr, The Journal of Esther Burr, 1754—1757, Carol Karlsen and Laurie Crumpacker, eds., (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), 235. All spelling found in this quote and all subsequent quotes are from the original.

[8]Greiff and Gunning, Morven: Memory, Myth and Reality, 28. Sadly, the friendship between these two women came to an end on April 7, 1758, when the twenty-six-year-old Esther succumbed to smallpox.

[9]Morvenwas the name of the castle of King Fingal, a mythic Scottish king found in The Works of Ossian, published by James Macpherson, 1765. Supposedly, Morven translates from the Celtic as “high hill or mountain.” For a brief history and present-day uses of this mansion that served as home to four generations of the Stockton family, a rental home of Robert Wood Johnson (1928 -1944) and the residence of five New Jersey Governors (1945-1981), see Morven Museum and Garden, morven.org.

[10]While there are no official records of the actual date of marriage it is believed to have taken place in late 1757 or early 1758. Annis and Richard had six children: Julia (1759), twins Mary and Susannah (1761), John Richard (1764), Lucius Horatio (1768), and Abigail (1773).

[11]Greiff and Gunning, Morven: Memory, Myth and Reality, 29.

[12]Richard was a Trustee of the College from 1757 until his death in 1781.

[13]Benjamin Rush, who was a graduate of the College of New Jersey, married Richard’s oldest daughter Julia in January 1776. Richard Stockton had spent a total of fifteen months in the British Isles.

[14]The Boudinots, who had been neighbors of the Franklins in Philadelphia, most likely knew William back then and through her literary connections remained in contact.

[15]Reportedly two of the boxes were found but one with silver and the papers were not. For this action, Annis (posthumously) was named an honorary member of the Whig Society, the only woman to achieve this honor. The Whig Society was a literary and debating club not part of the Patriot Whig Party.

[16]John Covenhoven was the vice-president of the Patriot New Jersey Congress.

[17]Four other Signers were taken as Prisoners of War: George Walton (Georgia), Thomas Heyward, Jr. (South Carolina), Arthur Middleton (South Carolina) and Edward Rutledge (South Carolina).

[18]The following is the oath needed to receive the pardon: “I, A. B., do promise and declare, that I will remain in a peaceable obedience to his Majesty, and will not take up arms, nor encourage others to take up arms, in opposition to his authority.”

[19]Col. William Harcourt of the 16th Light Dragoons used Morven as his headquarters.

[20]It has been reported that at least 2,500 New Jersey men took Howe’s pardon. For an excellent discussion of the effects on Richard Stockton due to his having taken the amnesty see: Christian M. McBurney, “Was Richard Stockton A Hero?,” Journal of the American Revolution, July 18, 2016, allthingsliberty.com/2016/07/was-richard-stockton-a-hero/.

[21]Interestingly, Richard, who was a practicing Presbyterian, was buried in the Stony Brook Friends Meeting Cemetery—the Meeting his grandfather joined when he moved to the area.

[22]Annis never remarried, although it is reported that she had at least two suitors: Samuel Stanhope Smith, a future president of the College (he was fourteen years younger), and Dr. John Witherspoon. Both men ended up marrying other women.

[23]Richard specified that his property was to be equally divided among his children, except for Morven, which he left to the eldest son (John) Richard (known as the “Duke”). A woman in this situation was usually referred to as a “dowager.”

[24]Greiff and Gunning, Morven: Memory, Myth and Reality, 45. This does not account for all enslaved people at Morven; according to New Jersey law only male slaves were counted for the tax rolls, not women nor minors.

[25]Annis Stockton to Elias Stockton, October 23, 1781, Thomas A. Glenn, ed., Some Colonial Mansions and Those Who Lived in Them (Philadelphia: Henry T. Coates & Co., 1898), 62.

[26]William T. Sherman, In the Number of the Best Patriots: Poetry of Annis Boudinot Stockton and Susanna Rowson, www.gunjones.com/Annis-Stockton_and_Susanna-Rowson.pdf.

[27]Washington to Elias Boudinot, February 27, 1779, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-19-02-0306.

[28]L.H. Butterfield, “Annis and the General: Mrs. Stockton’s Poetic Eulogies of George Washington,” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 7, no. 1 (November 1945): 19–39.

[29]Glenn, Some Colonial Mansions, 63.

[30]Annis Boudinot Stockton, Only for the Eye of a Friend: The Poems of Annis Boudinot Stockton, Carla Mulford, ed. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995), 106. A pastoral poem explores the fantasy of withdrawing from modern life to live in an idyllic rural setting.

[31]The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745—1799, Vol. 24, February 18, 1782 – August 10, 1782,John C. Fitzpatrick, ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1938), 437-438.

[32]While they convened in Princeton, the Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783 and word of the signing reached Congress on October 31, 1783. After leaving Princeton they reconvened in Annapolis.

[33]By this time all accommodations in Princeton had been taken and Mrs. Berrien, the widow of Judge John Berrien had the Rockinghamproperty for sale and was living in her home in Princeton; she agreed to a short-term rental. For a description Rockingham see: Rockingham State Historic Site: George Washington’s Final Wartime Headquarters, www.rockingham.net.

[34]Annis Boudinot Stockton to George Washington, August 28, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11759. Emeliawas her nom de plume.

[35]Annis Boudinot Stockton to George Washington, September 1, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11780.

[36]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, September 2, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-11784.

[37]William S. Baker, Itinerary of General Washington from June 15, 1775 to December 23, 1783 (Philadelphia: Lippincott Co., 1892), 269.

[38]Final evacuation of British troops from New York City took place on November 25, 1783.

[39]Stockton, Only for the Eye of a Friend, 121-130. This pastoral is 292 lines long!

[40]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, February 18, 1784, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-01-02-0096.

[41]Stockton, Only for the Eye of a Friend, 144-146.

[42]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, June 30, 1787,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-05-02-0222.

[43]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, August 31, 1788, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/04-06-02-0442.

[44]Annis Boudinot Stockton to Washington, March 13, 1789, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0298. The poem titled “The Vision, an Ode,” can be read at this site.

[46]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, March 21, 1789, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0324.

[47]For a description of the event see William S. Stryker, Washington’s Reception by the People of New Jersey in 1789 (Trenton: Printed for Private Distribution, 1882). In it he lists the “Matrons who took charge of the beautiful ceremonies”; on page 13 he gives a brief biography of Annis.

[48]Annis Boudinot Stockton to Washington, May 1, 1789,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0136. The poem can be read at this site.

[49]Washington to Annis Boudinot Stockton, May 4, 1789,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0149.

[50]Greiff and Gunning, Morven: Memory, Myth and Reality, 46.

[51]Famous Wives, Poets and Writers—Annis Boudinot Stockton, www.womenhistoryblog.com/2009/08/annis-boudinot-stockton.html.

[52]Stockton, Only for the Eye of a Friend, 28.

[53]L. H. Butterfield, “Morven: A Colonial Outpost of Sensibility. With Some Hitherto Unpublished Poems by Annis Boudinot Stockton,” The Princeton University Library Chronicle, vol. 1, no. 6 (November 1944), 9.

Recent Articles

Joseph Warren, Sally Edwards, and Mercy Scollay: What is the True Story?

This Week on Dispatches: David Price on Abolitionist Lemuel Haynes

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

Recent Comments

"Contributor Question: Stolen or..."

Elias Boudinot Manuscript: Good news! The John Carter Brown Library at Brown...

"The 1779 Invasion of..."

The new article by Victor DiSanto, "The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched...

"Quotes About or By..."

This well researched article of selected quotes underscores the importance of Indian...