On March 11, 1776, George Washington, headquartered at the Vassal mansion in Cambridge, Massachusetts, issued the following General Order to his officers:

“The General is desirous of selecting a particular number of men as a guard for himself and baggage. The Colonel or Commanding Officer of each of the established regiments, the artillery and riflemen excepted, will furnish him with four, that the number of wanted may be chosen out of them. His Excellency depends upon the Colonels for good men, such as they can recommend for their sobriety, honesty and good behavior. He wishes them to be from five feet eight inches to five feet ten inches, handsomely and well made, and as there is nothing in his eyes more desirable than cleanliness in a soldier, he desires that particular attention be made in the choice of such men as are clean and spruce. They are to be at headquarters tomorrow precisely at 12 o’clock at noon, when the number wanted will be fixed upon. The General neither wants them with uniforms nor arms, nor does he desire any man to be sent to him that is not perfectly willing or desirous of being in this Guard. – They should be drilled men.”[1]

The following day, Captain Caleb Gibbs of the 14th Continental Regiment was appointed Captain Commandant of the Guard and Lieutenant George Lewis second in command.[2] Aside from protecting Washington and his baggage, Gibbs and his Guards were also to protect the headquarters which meant its staff and all of the army’s records and to select the General’s living quarters upon any relocation. Personally, Gibbs also maintained Washington’s household receipt book.[3] The Guard began with 50 men.[4] The corps was reconstituted three times: the first time on April 30, 1777, the second time on March 1, 1778 and the third time on March 19, 1780; each time it became a little larger than previously. In April 1777 Washington asked Gibbs to procure uniforms for the corps, specifying “if blew or buff can be had, I should prefer that uniform for the corps, as it is the one I wear myself,” but noting that any other color except red would do. It is not if the same uniform was used throughout the war or whether all soldiers assigned to the guard received the same clothing. Some evidence indicates that their uniforms consisted of a dark blue coat faced with buff, a red waistcoat and buff breeches, while there is also evidence of blue coats with white facings, white waistcoats, and white breeches. Some sources indicate the use of a leather helmet with blue binding and a white plume, but primary sources indicate only hats with white binding.[5]Their flag or standard was made of white silk; it depicted a Guard holding a horse’s reins, and “in the act of receiving a flag from the Genius of Liberty, who is personified as a woman leaning upon the Union shield, near which is an American eagle.”[6] Over their heads is a banner bearing the words, Conquer or Die – their motto.

On December 11, 1776, Washington wrote to the Continental Congress, “From the experience I have had in this (the New York) campaign of the utility of horse, I am convinced there is no carrying on the war without them and I would therefore recommend the establishment of one or more Corps … In addition to those already raised in Virginia.”[7] On January 1, 1777, Lieutenant Lewis was promoted to captain[8] and given command of oneof the new troops of Light Horse. Because some the Guards enlistments had expired the day before, they decided to re-enlist but this time in Lewis’s troop. Even though the troop was assigned to Lt. Colonel George Baylor’s 3rd Dragoon Regiment, they were detached to serve as the Cavalry of the Commander-in-Chief’s Guard. Thereafter, cavalry detachments from each of the Continental cavalry regiments operated as part of the Commander-in-Chief’s Guard whenever required.[8]

In spite of efforts to have only men of “sobriety, honesty and good behavior,” a few men of Washington’s guard were implicated in a plot to undermine the rebellion in the second half of 1776; one of them was tried and executed for treason. On April 30, 1777, when sending out orders for new men for his guard detachment, Washington specifically asked for men born in America, but was also careful not to incite prejudice by doing so: “I am satisfied there can be no absolute security for the fidelity of this class of people, but yet I think it most likely to be found in those who have family connections in the country. You well therefore send me none but natives, and men of some property, if you have them. I must insist that, in making this choice, you give no intimation of my preference of natives, as I do not want to create any invidious distinction between them and the foreigners.”[9]

At Valley Forge the first group to be trained by Baron Von Steuben in his ‘’Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops” were the Guards. “One hundred chosen men are to be annexed to the Guard of the Commander in Chief for the purpose of forming a Corps to be instructed in the maneuvers necessary to be introduced in the army and serve as a model for the execution of them … The one hundred draughts are to be taken from the troops of the states.”[10]

In late spring of 1780, German Lt. General Knyphausen learned that General Washington’s army in Morristown was shrinking due to disease and desertion. He immediately set in motion a plan to attack. At midnight on June 6, he and a force of 6,000 men crossed from Staten Island to Elizabethtown Point, New Jersey. His plan was to capture Elizabethtown, Springfield, and Hobart Gap in one day; the next day he would take his men though the Gap, which was the only pass through the Watchung Mountains, and then march the eleven miles to Washington’s encampment.

At dawn the American piquets were alerted but could do nothing but retreat. At Elizabethtown Knyphausen and his men were confronted by a detachment of the New Jersey Continental Brigade under the command of Colonel Elias Dayton and some militia. After a brief skirmish Dayton and his men were forced to retreat to the town of Connecticut Farms but not before Dayton directed his son to write a letter to General Washington at Morristown apprising him of the situation. At 8:00 am. Knyphausen’s men reached a defile that led into the town of Connecticut Farms; it was guarded by General Maxwell’s New Jersey brigade. After a three hour battle that had ebbed and flowed Maxwell and his men were forced to retreat when Knyphausen received

reinforcements. On the west edge of town Maxwell regrouped was able to drive Knyphausen’s advance guard back to the main body before being forced to retreat across the Rahway River. With the day growing long and militia “flocking from all quarters”, Knyphausen decided to halt his march.[11]Late in the afternoon, some of Washington’s Guards under the command of Major Gibbs arrived. The records are unclear, but sometime thereafter as Knyphausen and his men were retiring to the safety of ‘high ground’ near Elizabethtown, Gibbs and the Guards harassed their retreat “and gave the Hessian Lads a charge just before sunset … We gave them after they gave way about 8 rounds.”[12]

On April 23, 1781, Major Caleb Gibbs left his position as Commandant of the Guard and transferred to the 2nd Massachusetts Regiment[13]; Captain William Colfax, having joined the Guard on March 1, 1778 from the 1st Connecticut Regiment, assumed command.[14] The Guard’s ability was again tested on July 3, 1781. Washington had spent weeks reconnoitering British positions around New York and planned a surprise attack on the British post at King’s Bridge, the northern passage from Manhattan Island to the mainland. He sent a battalion of select light infantry to conduct the operation, but they ran afoul of Hessian scouting parties operating in the area and were soon attacked by Hessian cavalry. A long and complex action ensued in which Washington’s Guards were involved and suffered many casualties, although their precise role in the battle is not clear. A soldier of the light infantry wrote,

“After retreating about a mile … a body of French Cavalry hove in sight, and immediately after the front of the main army under Washington appeared. On discovery of this large force, the enemy gave up the pursuit and retired over the bridge … I assisted in moving one poor fellow who was shot through the body. He … belonged to Gen. Washington’s … Guard.“[15]

A deposition given by Nathan Nunn Lounsberry of Lamb’s Artillery years later, indicated that the artillery marched “to Valentine’s Hill [the height above King’s Bridge] to reinforce Gen’l Washington’s Lifeguards, who had been attacked by the Hessians – come up in time to give then a few shots, when the Hessians retreated …”[16] Second Lieutenant Levi Holden’s report on July 11 to Captain Robert Pemberton listed the Guards’ casualties as “one lieutenant and one sergeant wounded – fourteen rank and file wounded – one missing, and three of the wounded since dead.”[17] In the Revolutionary War Pension Records, there are affidavits attesting to the fact that Luther Smith, a Guardsman, “suffered a leg wound caused by a bayonet.” This indicates that the Guard was involved in close fighting at some point in the action.[18]

After General Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, the Guard retired to the Hudson Highlands in New York and eventually settled at Newburgh in the spring of 1782. On June 6, 1783, sixty-four were furloughed until the ratification of the Treaty of Peace.[19] Only 38 Guards remained – 12 of whom were mounted.[20] On November 9, Washington gave his final order to his Guards. Captain Bezaleel Howe and 11 of them were to escort his six wagons of baggage to Mount Vernon.[21]Howe had served under Major William Scott until he was transferred to Washington’s Guard on September 5, and had been promoted to the rank of Captain on October 10, one month before Washington’s final order. The remaining Guards were detached and re-assigned to the garrison at West Point, and those who had been furloughed on June 6 were discharged. Washington’s baggage arrived without incident on December 20, three days before he himself arrived safely at his home.

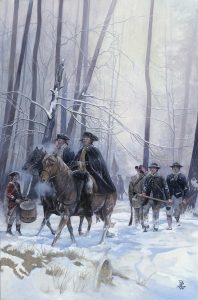

[FEATURED IMAGE AT TOP: “Williamsburg to Yorktown” by Pamela Patrick White (whitehistoricart.com)]

[1] John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799 (Washington DC: GPO, 1934), 4:387-88.

[2] Benson Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution (New York: Harper, 1851-52), 2:594.

[3] W. C. Ford, ed., The Writings of George Washington (New York: 1890), 7:111.

[4] Philander D. Chase, ed., The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999), 9:236.

[5]Philip R. N. Katcher, Uniforms of the Continental Army (York, PA: George Shumway Publisher, 1981), 51.

[6] Lossing, The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, 120.

[7] Ford, The Writings of George Washington, 5:80: The Papers of the Continental Congress, No. 152, Vol. III, folio 339.

[8] Jenn Winslow Coltrane, Lineage Book : National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution (Washington DC: GPO, 1921), 57:3.

[9] Carlos Emmor Godfrey, The Commander in Chief’s Guard, Revolutionary War

(Washington, DC: Stevenson-Smith Co., 1904), 40.

[10] Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 8:179.

[11] Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 11:98.

[12] Nicholas Murray, Historical and Biographical Concerning Elizabethtown, New Jersey: its Eminent Men, Churches & Ministers (Elizabethtown, NJ: E. Sanders, 1844).

[13] Scammel, Alexander. “Return of the kill’d, wounded, missing and deserted since the 6th instant: Head Quarters, near Short-Hills, June 20th 1780″. George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741–1799; Caleb Gibbs to William Maxwell, June 8, 1780,” George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 4. General Correspondence. 1697-1799.

[14] “General Orders, 23 April 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives.

[15] “A Short Sketch of the Life of Asa Redington,” Special Collections, MSS Collections, Misc 383, Stanford University Library, 1838.

[16] Pension Application of Nathan Munn Lounsberry, Revolutionary War Pensions, www.fold3.com

[17] http://memory.loc.gov/mss/mgw/mgw4/079/0500/0595.jpg; Edward Hand was

Washington’s Adjutant General.

[18] Pension file of Luther Smith, Revolutionary War Pensions, New Hampshire, Luther Smith, www.fold3.com, 17.

[19] Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 26:448, 464-65, 471-75; 27:6-7, 10, 15,

19-20, 25-26, 32-34, 38-39.

[20] Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Vol. X, 399.

[21] Howe Family Papers, Mss Group 427, New Jersey Historical Society.

8 Comments

Thank you for a wonderful article! I grew up in Morristown, NJ and am familiar with many Rev. War sites including Hobart Gap Road which is now Rt 24 rising out of Springfield NJ – another great battle – over the top of the hill to Summit, NJ and down to Chatham. Even though modernization has changed so many features of the original landscape, you can still see the advantages of the Gap while driving through it. I can understand the British desire to capture Morristown and Hobart Gap was the way! Try driving through the gap and if you are thinking about the Rev. War, try imagining the British desperately attempting to climb up through it under Continental musketry and marksmen fire.

Also, more in tune with the article, It`s remarkable that other people did not attempt to harm Washington given the extremely divisive nature of a civil war. Are there any other people besides his early Continental Guard which attempted to undermine if not down right kill him!

Thanks for a great article!

John Pearson

Thanks Bob, nice article! I was not aware that Washington’s Life Guard was in these military engagements. It appears you really dug deep to discover those, well done.

Thanks, Bob, for your description of the Battle of Connecticut Farms and the involvement of General Washington’s Life Guard.

I am a direct descendant of William Pace of Virginia. He enlisted in the 14th Virginia Regiment commanded by Colonel Lewis on January 23, 1777. He was recommended by Col. Lewis for assignment to Washington’s Life Guard when it was first reconstituted in the spring of 1777.

Each regiment was requested to send four members to be interviewed by General Washington himself. After the attempted assassination of Washington in 1776 by a non-native born Guard member and others, only native born Americans were acceptable to the General when the Guard was reconstituted in 1777. William Pace was selected by Gen. Washington and then served in Washington’s Guard throughout the rest of the Revolutionary War.

According to records researched by Pace family members (published in THE BELLOMY/BELLAMY AND PACE FAMILIES AT A PLACE CALLED

DOVER, written and illustrated by William and Martha Bellomy, Copryright

1999), Pace fought in every battle that Washington led or was present, including the Battle of Connecticut Farms in June 1780. His fought in his last battle fought at Yorktown in October, 1781. Pace was promoted to Sargent just before being furloughed in June, 1783, then was discharged when the Guard was dissolved in November 1783.

As you described, Washington’s Life Guard was not just a personal bodyguard, but also fought on the front lines of all of the battles along with the regular troops.

I am also a descent of William Pace. I am a descent through the Bellamy side. I would love to find more information on the Life Guard.

I am a documented descendant of Life Guard, James Knox of Massachusetts. Does anyone know whether there is a lineage society dedicated to descendants of General Washington’s Life Guard?

The Sons of the American Revolution’s Color Guard, based in California, of which I am a member, modeled their uniforms on the Commander in Chief’s Life Guard. Note the bear fur dragoon’s helmets in the lead illustration for this article. We even obtained replicas of these. We used [9] Godfrey (above) extensively as a resource. We have members of this color guard all over the United States. We also have a journal, the “SAR Colorguardsman” (https://sar.org/sar-colorguardsman).

I myself was in the Army Old Guard, specifically Alpha company-CINC Guard (Commander in Chiefs Guard). I enjoyed the reading, learning more history about the unit helped me to better understand some of the traditions I was a part of. Thank you

My ancestor Jacob Wellman may have been in the guard. There’s a not in a history written about Milford NY men in the war. It mentions Jacob Wellman Marshall of the Guard at Major Andre’s hanging.

Is there any way to verify/authenticate?