General George Washington stood in front of his assembled officers, reading glasses in hand, and stated, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind, in the service of my country.”[1] These words uttered on March 15, 1783, in the recently constructed Temple of Virtue at the New Windsor Cantonment, were arguably the crescendo of eight years of military leadership over the Continental Army. Washington defused the Newburgh Conspiracy, the most severe threat to the emerging peace. General Washington’s performance was not only a demonstration of his character, but a masterful display of leadership driven by high emotional intelligence.

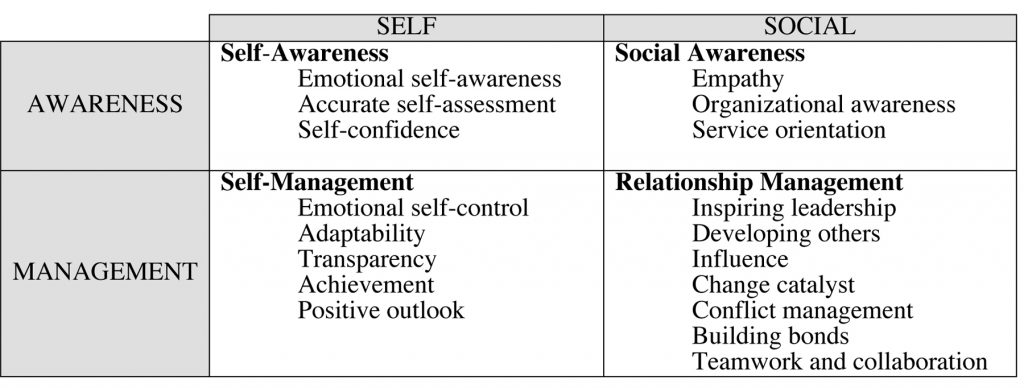

Emotional intelligence (EI) refers to the emerging field of psychology positing that the awareness and regulation of emotions is one measure of intelligence. It is analogous to the way researchers compare cognitive intelligence with intelligence quotient (IQ). In the mixed-trait model of emotional intelligence popularized by Daniel Goleman, EI is the “ability to monitor one’s own and other people’s emotions, to discriminate between different emotions and label them appropriately, and to use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior.”[2] Within each of these four categories, Goleman found eighteen specific characteristics that describe the level of emotional intelligence in an individual.

Daniel Goleman’s Model of Emotional Intelligence[3]

Researchers increasingly find that the highest-achieving leaders possess high emotional intelligence. At an individual level, “EI is the single biggest predictor of performance in the workplace and the strongest driver of leadership and personal excellence.”[4] Other studies found that leaders who can perceive their own and others’ emotions at the moment are more effective in teams and more positively affect their organization.[5] Historians primarily judge Washington as a very effective leader, which this study posits was influenced by his capacity to perceive and act on emotion.

George Washington demonstrated a high level of emotional intelligence throughout March 10-15, 1783, in defusing the proposed mutiny of colonial officers encamped in the vicinity of the New Windsor cantonment. When viewed through the modern construct of EI, Washington showed that he understood both his own and the officers’ emotional states. He used this knowledge to regulate his emotional response and manage relationships within the officer corps.

On the 10th of March, Washington became aware of an anonymous summons to gather the officers of the Army on the 12th to consider options for the “redress of grievances” to the Congress.[6] Accompanying this summons was a long anonymous letter that articulated the insults endured by officers through Congress failing to provide necessary pay and pensions.[7] The letter writer argued to “change the milk and water” form of previous memorials into more vigorous action lest the insult of congress “drive you into dishonor.”[8] Upon receipt of the letters, Washington became “amazingly agitated” because the “implicit challenge to Washington’s authority” was “derogatory to the good order of the Army.”[9] This was shocking to those accustomed to the general’s carefully curated presence and demonstrated the profound effect of the letter.

Washington revealed his emotional awareness and ability to regulate his emotions through the immediate response to the letter. Instead of choosing a severe course, Washington issued general orders on March 11 canceling the proposed meeting and convening an assembly the following Saturday, headed by a senior officer, to consider actions “most rational and best calculated to attain the just and important object in view.”[10] In doing so, he took the initiative back from the scheming officers while simultaneously demonstrating an understanding of their just grievances.

The commander in chief displayed empathy for the plight of the officers. Empathy is the ability “to recognize, understand, and share the feelings of others” and is key to relationship management.[11] In December, Washington wrote to Congress indicating that the “temper of the Army is much soured . . . more irritable than at any period.”[12] At stake was the honor of officers who would return home in debt and without due reward for their suffering and service. In the eighteenth century military view, “honor guided the officer in delicate affairs like paying debts and dealing with insults.”[13] And when duty conflicted with honor, the latter took precedence.[14] The commander’s empathy now stood in tension with the “disapprobation of such disorderly conduct” of the proposed assembly.[15] Washington had to find a way to lead his army away from the edge of revolt while maintaining the trust, control, and respect of both his officers and Congress.

Washington’s next moves revealed his ability to not only restrain his emotions but adapt his responses to the situation at hand. First, he published general orders on the 13th which, in addition to routine business, revealed a congressional resolution from January outlining the way ahead to provide for just compensation for officers. This action set the stage for Washington’s primary argument – trust Congress to provide.[16] Second, he wrote a series of letters to members of Congress. His official report to Elias Boudinot, president of Congress, informed him of the entire situation, provided all anonymous documents, and expressed optimism in handling the situation if Congress acted in support of the officer’s petitions. To Alexander Hamilton and Joseph Jones, both members of Congress, he was freer with his language in describing the severity of the situation. Both the Hamilton and Jones letters were nearly identical in advocating urgent action by Congress before the revolution was at risk.[17] Washington’s EI was at work in the separate messages because he knew full well that Hamilton and Jones were allies in the effort to spur Congress to act. They would use the information to build support in Congress without further inflaming the passions of the officers.[18]

Washington next used a combination of inspirational leadership, influence, and collaboration in meeting with officers individually in the days leading up to the meeting. William Gordon reported that “the general sent for one officer after another and talked to them privately to set before them the ill consequences of violent measures, and the loss of character that would follow; and brought several to tears.”[19] Individuals are often easily swayed by the power of group dynamics. Therefore, Washington wisely forced numerous officers to look him in the eye and consider his arguments, convincing “once loyal ranking officers . . . to stand with him.”[20] Even if the “bringing to tears” line is somewhat exaggerated, the report indicates that he used his power of personal persuasion to set the stage for the Saturday meeting.

The meeting day provided Washington the opportunity to fully display his EI in exercising leadership over the assembled officers. His general order convening the gathering gave no indication he would attend the meeting, but he came with well-rehearsed remarks evidenced by the many notes made on his manuscript.[21] According to one historian, “The man who faced bullets with sangfroid never conquered his terror of public speaking.”[22] He understood his weakness and the importance of public communication to influence the group, so he prepared accordingly.

Washington was aware of the challenge before him, given the depth of emotion among the officer corps. Historian James Flexner reported that “for the first time since he had won the love of the army, he saw facing him resentment and anger.”[23] To influence, it is first necessary for the leader to align with the group. “If there is no alignment around shared goals and work, then the influencer has failed.”[24]

So as he began, his tone was respectful of the audience, and “instead of elevating himself above his men, Washington portrayed himself as their friend and peer.”[25] Additionally, he “lifted them to a higher plane, reawakening a sense of their exalted role in the revolution and reminding them that illegal action would tarnish that grand legacy.[26] According to Maj. J.A. Wright the General was “sensibly agitated”[27] during parts of the speech, but “he knew how to control his despair, . . . his frustrations and anger,” another hallmark of high EI.[28]

Washington appealed next to reason and logic to convince the officers of the error of their course. He argued at length about the calamity resulting from the intended course of action and the need to trust Congress to provide the desired remedy. At this point, His Excellency may have missed the mark on exerting inspirational leadership. “After completing the speech, the officers appeared unmoved,”[29] and Washington must have wondered if his mission had failed.

After the end of the prepared remarks, Washington reached the crescendo of his display of EI. He reached for a backup letter from Joseph Jones, a member of Congress, to ensure the officers understood the position of that body. It was then that he pulled out his new reading glasses and stated, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind, in the service of my country.”[30] “Hearts melted. Tears flowed. Washington . . . continued over the sobs.”[31] Whether Washington planned or improvised this gesture makes little difference, as the reasons for his behavior were “so deeply buried in his character that they functioned like a biological condition requiring no further explanation.”[32] His long-developed character was comprised, in part, of a high EI that allowed him to understand his men and connect with them in an intimate way that accomplished what was impossible through rhetoric or reason alone.

Managing relationships through influence cannot happen without trust. After the meeting, the officers unanimously “reciprocated his affectionate expressions” and declared their support for Washington’s plan.[33] Interactional justice, however, is a primary driver of trust between leaders and the organization.[34] To maintain that trust and influence, Washington needed to ensure Congress adequately answered the officers’ grievances. So, the general continued his letter-writing to Congress informing them that the immediate crisis passed but they must “give every satisfaction that justice requires.”[35] This is emotional intelligence at work, as Washington understood his speech was only a temporary reprieve from the foul organizational mood. He ultimately successfully attained the object of the officers’ grievances and arguably saved the entire revolution.

George Washington resigned his commission just a few short months later when nearly the entire army peaceably returned to civilian life. Of the many ways Washington is an exemplar for modern strategic leaders, his exercise of emotional intelligence during the Newburgh Conspiracy continues to provide relevant instruction today. At that critical time in the new nation’s history, the commander in chief was able to engage his own and others’ emotions and used that information to guide his thinking and behavior. In doing so, he proved that his place in the history of leadership is well justified.

[1]David Head, A Crisis of Peace: George Washington, the Newburgh Conspiracy, and the Fate of the American Revolution (New York: Pegasus Books, 2019), 150.

[2]Kalpana Srivastava, “Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Effectiveness,” Industrial Psychiatry Journal 22, no. 2 (2013): 97–99, doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.132912.

[3]Daniel Goleman, Richard E. Boyatzis, and Annie McKee, Primal Leadership: Unleashing the Power of Emotional Intelligence (Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press, 2013).

[4]Travis Bradberry and Jean Greaves, Emotional Intelligence 2.0 (San Diego, CA: Talent Smart, 2009), 23.

[5]Tanekkia Taylor-Clark, “Emotional Intelligence Competencies and the Army Leadership Requirements Model” (Fort Leavenworth, KS, Command and General Staff College, 2015); Srivastava, “Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Effectiveness.”

[6]George Washington to Elias Boudinot, March 12, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10818.

[7]The letter was anonymous at the time. It was written by twenty-four-year-old Maj. John Armstrong, Jr., serving as aide-de-camp to Gen. Horatio Gates.

[8]Washington to Boudinot, March 12, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10818.

[9]Head, A Crisis of Peace, 134.

[10]General Orders, March 11, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10811.

[11]Raquel Gómez-Leal et al., “Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Empathy towards Humans and Animals,” PeerJ9 (April 16, 2021): e11274, hdoi.org/10.7717/peerj.11274.

[12]Washington to Joseph Jones, December 14, 1782, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10202.

[13]Christopher Duffy, The Military Experience in the Age of Reason (New York: Atheneum, 1988), 75.

[15]Washington to Officers of the Army, March 15, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10840.

[16]Head, A Crisis of Peace, 135.

[17]Washington to Jones, March 12, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10821; Washington to Alexander Hamilton, March 12, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10820.

[18]Alexander Hamilton was part of a faction that used fear of the officers’ reactions to influence Congress and the states to tax imports to raise money for the army and nation. Washington warned Hamilton that the “the Army (considering the irritable state it is in—its sufferings—& composition) is a dangerous instrument to play with.” Washington to Hamilton, April 4, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10993.

[19]Head, A Crisis of Peace, 143.

[20]James Martin and Sean Hannah, Leading With Character: George Washington and the Newburgh Conspiracy (Alexandria, VA: George Washington Leadership Institute, 2017), 406–7.

[21]James Thomas Flexner, Washington: The Indispensable Man (Boston: Little, Brown, 1974), 241; Newburgh Address, March 15, 1783, www.masshist.org/database/1742.

[22]Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (New York: Penguin Press, 2010), 99.

[24]Ed O’Neil, “Using Emotional Intelligence to Influence,” Quick Takes for Medicaid Leaders Amid COVID-19, May 2020, www.chcs.org/media/QuickTakes-EI-to-Influence_052620_final.pdf.

[27]Head, A Crisis of Peace, 145.

[28]Ibid.; Martin and Hannah, Leading With Character, 92–93.

[29]Paul S. Vickery, George Washington: Legacy of Leadership (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, Inc., 2011), 204.

[30]Head, A Crisis of Peace, 150.

[32]Joseph J. Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 186.

[33]Washington to Horatio Gates, March 15, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10841.

[34]Samuel Aryee, Pawan S. Budhwar and Zhen Xiong Chen, “Trust as a Mediator of the Relationship between Organizational Justice and Work Outcomes: Test of a Social Exchange Model,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 23, no. 3 (May 2002): 267–85, doi.org/10.1002/job.138.

[35]Washington to Jones, March 18, 1783, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-10858.

3 Comments

Thank you for such a well written and researched piece. I have long felt this was one of the critical victories that won the war. Were it not for this moment our revolution could have gone the way of the France’s.

And thank you for your service.

The story about Washington pulling out his glasses and saying he had nearly gone blind is based on a book written fifty years later. The story is likely false.

An excellent addition to the Newburgh Conspiracy. I would add that many historians, myself included, do not doubt Washington’s capacity for leadership, i.e. reading the room and knowing his men better than anyone. However, one cannot entirely dismiss the possibility that the second ’emotional’ address where he pulled his spectacles from his pocket was not an act of political theater. It is entirely possible Washington staged what he did to play on the emotions of the men in the room. What they were witnessing: a vulnerable GW in a visibly aged state that shook them out of their temptation of committing the unthinkable. What we regard as spontaneity may very well be so, but born from Washington seeing he had to act fast in the moment, and call upon a bit of emotional theater to regain the room, and the confidence of his lieutenants in his judgment.

Also, that Hamilton was receiving and corresponding with Washington about the mood of the senior officer corps must be viewed through the lens of knowing Hamilton and Robert Morris very much had instigated the very discontent now sweeping through Newburgh. The two delegates of the Confederation Congress were scheming to undermine the Articles of Confederation, and using an angry army as a threat to reform the monetary powers of Congress was something they openly discussed to each other and with a few officers at Newburgh. Of course, they downplayed their involvement after the fact. Washington, unaware of this, wrote to Hamilton thinking he remained one of his trusted former lieutenants. Hamilton, ever the career climber, tried to hide his involvement. But when GW found out, he promptly warned Hamilton, among other things, “The Army is a dangerous instrument to play with.”