The Bliss Family roots run deep in Connecticut. Born in England around 1618, Thomas Bliss became a founder of Hartford and Norwich, Connecticut before passing away in 1688 in Norwich. His name is marked along with several others on a lone stone obelisk in the original Norwich Founders Cemetery, erected in the nineteenth century. Thomas Bliss married Elizabeth Birchard (1621-1699) in New London in 1644 and established their home lot along Norwich’s present-day Washington Street. The Bliss, Leffingwell, Backus, and Reynolds family properties abutted each other on the land now occupied by the William W. Backus Hospital and the current intersection where Connecticut Route 2 meets Washington Street; only one of these homes, the historic Leffingwell Inn still remains, now operating as the Leffingwell House Museum. The Inn was the only home to be saved and relocated between 1957 and 1960 to allow for the Connecticut Route 2 construction.

For several generations, the Bliss family lived and thrived on their family plot. Thomas Bliss’s son Samuel was a local merchant and conducted coastal and international trade for many years. Historian Mary Perkins highlights some interesting details regarded as dubious in the eyes of the Church. On two separate occasions, Samuel Bliss was accused of selling libations to Native Americans and his wife Ann faced a punishment too before being “restored” back into the congregation’s good graces in 1736.[1] Samuel’s son, also named Samuel, inherited the homestead from his father before leaving it to his son John, who left it to his son, also named John. John Bliss II (1749-1815) had three younger brothers, Elias (1750-1833), Zephaniah (1753-1827), and William (1766-1844).

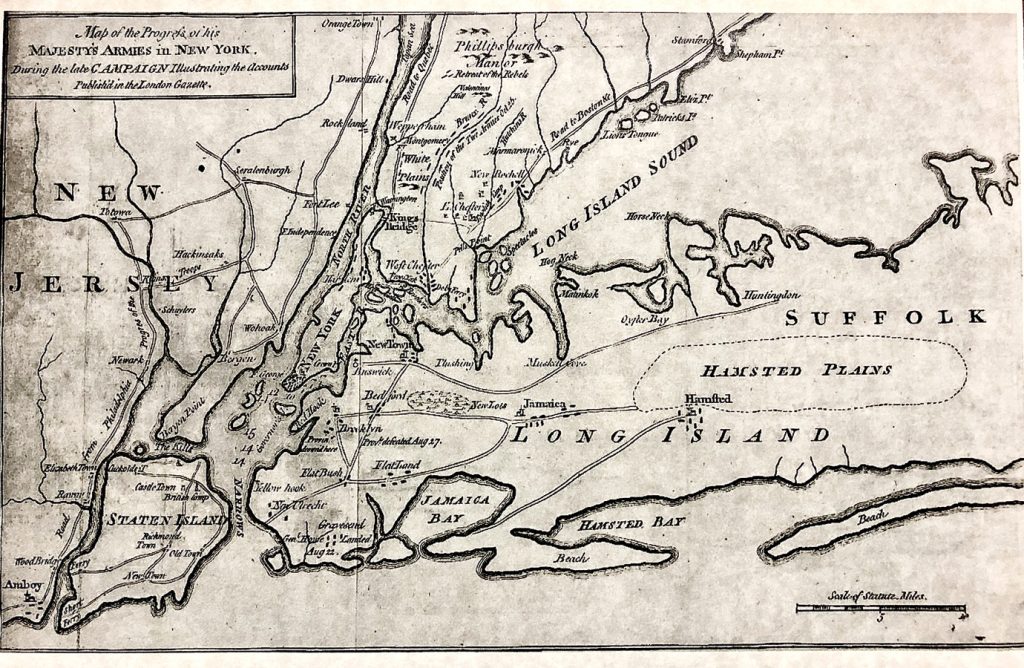

Upon the outbreak of the American Revolution, numerous militia units comprised of young men from Norwich mustered to serve in the Continental Army; the Bliss family was no exception. On September 8, 1776 Capt. Joseph Perkins of the 20th Connecticut Regiment of Militia issued general orders delivered to Zephaniah Bliss, now a sergeant in the regiment, stating, “all the men under my command in said Company to be at the usual place of parade tomorrow morning at nine complete in arms for a march.”[2] Sergeant Bliss led the 1st Company of the 20th Connecticut Regiment, Norwich unit, commanded by Norwich’s Col. Jedediah Huntington. Huntington led the regiment from its inception in October of 1774 until May of 1777 before being promoted to brigadier general; Col. Samuel Abbot assumed command from 1777 to 1780 and Col. Zabdiel Rogers until the war’s end. The following morning, Sergeant Bliss mustered with his fellow militiamen and departed Norwich for Rye, New York. It is unknown whether he was aware at the time that the situation in New York was perilous. Surviving correspondence written by Zephaniah to his younger brother Elias, who remained behind in Norwich, reveals key details that the company encountered during their encampment outside Manhattan.

After a failed defense on Long Island, General Washington succeeded in evacuating his entire army of 9,000 troops without a single loss of life across the East River to Manhattan, concealed only what was described as divine providence disguised as a thick fog. By the time General Clinton landed 5,000 regulars at Harlem Heights on September 16, Sergeant Bliss and the 20th Connecticut Regiment were about a day away from reaching their encampments just over twenty miles away. The regiment marched for nine days from Norwich and Sergeant Bliss wrote to his brother Elias on September 24, 1776 stating, “Dear Sir . . . I take this opportunity to let you know that I am well after a march of 9 days and that we are stationed here in a much better situation than our Friends below . . . we are stationed on a very fine creek that affords a plenty of blackfish, oysters, clams and eels.”[3] Sergeant Bliss was never deployed to the front lines but rather was tasked with other men in his company to guard the storehouses and stocks of provisions. In his correspondence, Sergeant Bliss relayed information to his brother of a massive fire which broke out towards the southern tip of Manhattan which consumed an overwhelming number of buildings; both the British and Americans suspected each other of arson but no evidence emerged implicating a clear suspect. Before Sergeant Bliss sealed his letter for delivery, he made a last-minute addition in the form of a postscript, “we are informed that Capt. Hale of New London was taken as a Spy in New York and was hung yesterday.”[4] Although Sergeant Bliss noted that Connecticut’s state hero Nathan Hale was hanged on September 23, his hanging actually occurred on September 22.

Sergeant Bliss remained stationed in Rye throughout September, October, and November of 1776. His next letter dated October 10 to Elias described an inevitable outbreak of disease due to “camp distemper.”[5] In spite of this, he reported no fatalities and described the morale of his company as remaining strong but undoubtedly wary of the hidden threat of disease.[6] While General Washington and his army continued to move north out of Manhattan, General Howe kept up a two-pronged strategy of harassing the rebel garrisons via waterways, while ultimately aiming to flank Washington’s forces through a series of amphibious landings. Sergeant Bliss noted that the British ships fired numerous volleys upon their positions, but they remained in place without any losses. Another striking detail that Sergeant Bliss reiterated is when he stated, “as to our fare, we have a very fine barrack and live very well as to provision much better than expected.”[7] After about a month-long standoff, the British maneuvered on October 12 to intercept the Continental Army via the juncture of Throgs Neck, also known as “Throggs” Neck, or as Sergeant Bliss called it, “Frogs Point.” Sergeant Bliss wrote to his brother on October 14 thanking him for sending a supply of “mintwater,” among some other provisions, and informed him that he thus far had evaded illness, stating, “By our last regimental return we had 178 privates in our regiment 45 of which are sick how soon it will be my turn God only knows.”[8] Sergeant Bliss noted that the British had landed as many as 6,000 troops on the point but, to their dismay, discovered that there was only one practical means of accessing the mainland, which was over a causeway connecting the two sides. The Americans thwarted the British advance by pulling up all the planks on the causeway bridge, causing the British to retreat back to the island at Throgs Neck where they encamped for almost a week before making landfall outside Pelham. A force of 750 militia under the command of Col. John Glover met thousands of British regulars in a skirmish known as the Battle of Pell’s Point. These calculated delays and standoffs produced the strategic victory for Washington’s main army, which prevented a near fatal defeat.

In the same letter from October 14, Sergeant Bliss also went into an account from the previous week, in which a separate company of American militia endured a horrific friendly fire incident. He wrote, “Last fryday one of our own boats was passing one of our Batteries with 12 men in her and was fired upon from the battery with a 12 pounder . . . which killed three men instantly and took an arm of the fourth and then they came to this morning”; the remaining soldiers beached the vessel on shore and were met by nearby companies in addition to a “Capt. Niles,” who proved to be Capt. Robert Niles, also a Norwich, Connecticut native.[9] The day after this letter on October 15, Sergeant Bliss and his fellow companies marched towards Mamaroneck, five miles from their encampments to meet a reported British landing but it turned out to be a false alarm. A week later on October 22, a skirmish at Mamaroneck did break out between Col. John Haslet and his 1st Continental Delaware Regiment and Lt. Col. Robert Rogers and his legendary Queen’s Rangers. Though Colonel Haslet’s regiment inflicted more casualties against the enemy, the Queen’s Rangers ultimately drove them back.

Though Washington was beaten, he was not defeated. The events described by Sergeant Bliss allowed Washington and his Continental forces to evade capture, but not before a final engagement outside White Plains, New York on October 28, 1776. Sergeant Bliss’s last letter to his brother dated November 7, 1776 highlights some of the smaller engagements in the aftermath of the battle:

Dear Brother, I take this opportunity to let. You know that I am well and hope these will find you so. As for news there is nothing very material. Last Sunday the Enemy attacked us here . . . they had about 1500 men Four Field Pieces Several wagons on which was mounted some swivels . . . we took 2 of their men prisoner and they one of ours which they let go. We had not one man killed.[10]

This letter also includes a provocative detail surrounding an individual Sergeant Bliss identifies as “Mr. Avery a Church Priest.”[11] Mr. Avery turns out to be Rev. Ephraim Putnam Avery born in 1741 in Pomfret, Connecticut to Rev. Ephraim Avery Sr. and Deborah Lothrop of Norwich. Rev. Ephraim Avery Sr. passed away in 1754 and Deborah Lothrop remarried twice afterwards to John Gardiner and later Gen. Israel Putnam in 1767. The younger Reverend Avery graduated from Yale College in 1761 and later was ordained by the Church of England. Reverend Avery aligned himself with the British and his reputation as an infamous Tory earned him the wrath of his community.[12] After suffering a debilitating stroke in 1776, which left him partially paralyzed, his wife Hannah Avery died on May 13, 1776 at the age of thirty-nine. His sudden decline in health compounded by the loss of his wife inflicted an inescapable amount of trauma on Reverend Avery who was discovered dead on the morning of November 5 in an apparent suicide. Sergeant Bliss wrote that the reverend “cut his own throat . . . he was son to the wife of General Putnam . . . he left 5 small children which our Major sent back into the country the same day.”[13]

Providence shined on Zephaniah Bliss and returned him safely home to Norwich, where he passed away in 1827 at the age of seventy-four. His brother Elias passed away in 1833 at age eighty-three. Both men are interred in Norwich’s colonial burial ground, with Sergeant Bliss’s name commemorated on a plaque outside the main gates along with other Revolutionary War veterans from Norwich. Sergeant Bliss signed his last letter to Elias, “I shall conclude by signing myself your friend and living brother.”[14]

[1]Mary Perkins, Old Houses of The Antient Town of Norwich 1660-1800(Norwich: Press of The Bulletin Co., 1895), 32.

[2]To Zephaniah Bliss from Jacob Perkins, September 8, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[3]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, September 24, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[5]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, October 10, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[6]In this letter, Zephaniah Bliss also noted that paper and ink were “scarce” and that he was unable to write to others inquiring about his status. Four of Zephaniah Bliss’s letters are known to survive and are kept within the collection of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[7]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, October 10, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[8]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, October 14, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[10]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, November 7, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

[12]Franklin Bowditch Dexter, Biographical Sketches of the Graduates of Yale College with Annals of the College History Vol. II May, 1745-May, 1763 (New York: Henry Holt and Co., 1885), 686.

[13]To Elias Bliss from Zephaniah Bliss, November 7, 1776, Archives of the Society of the Founders of Norwich.

4 Comments

Norwich, Rye, Pomfret,York. I was at school with a boy called Bliss. These homely English names point up the domestic nature of the fight to free the colonies of Crown authority, despite the ocean’s divide and the alien shore.

A small point, perhaps, but General Howe’s men crossed to Manhattan on 15th September 1776, landing at Kips Bay. After a chaotic retreat, Washington managed to stabilise his army that night behind a defence line on Harlem Heights, from where they issued forth the next morning, 16th September, to engage British light infantry probing forward from positions in the woods to the south- the running battle that resulted coming to be known as ‘Harlem Heights.’ Both armies ended the day where they started.

Thank you for your reply Arthur – hope you enjoyed it!

Marvelous letters, and apparently unpublished otherwise? Thank you for this research!

Thank you for your reply Brenda! Glad you enjoyed it.