On a trip to the southern colonies in 1773, Josiah Quincy of Massachusetts visited the coastal region of North Carolina. He was introduced to North Carolina Patriot leadership, toured coastal Fort Johnston, and visually inspected the disposition and military capabilities of the South. It was on this southern tour that Quincy, a Boston born Patriot and close friend of John Adams and Samuel Adams, encountered Cornelius Harnett of Wilmington. After dining with Harnett one evening, their conversation was so cordial that they agreed to a “continental correspondence,” or plan to write on all things revolutionary.[1] The conversation and cordiality blossomed into friendship; Quincy’s highest praise for Harnett was calling him “the Samuel Adams of North Carolina.”[2] Quincy’s intimate knowledge of the Revolutionary sentiments of the Adams family and the revolutionary nature of the Sons of Liberty made this compliment a true reflection of Harnett’s patriotic fervor. The cause in the southern colonies desperately needed a man of such strong sentiments to lead as war began in the mid 1770s.

In 1775 North Carolina needed all the revolutionary, Adams-like men it could muster. Revolutionary events in New England had begun influence activities in the middle and southern colonies. From the North Carolina delegation of the Continental Congress, Joseph Hewes, Samuel Hooper, and Richard Casewell wrote a letter of proclamation to the inhabitants of their home state, reflecting on the recent bloodshed at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts in April 1775. War had begun. The North Carolina representatives requested by “ties of religion virtue and love of your country . . . follow the example of your sister colonies and to form yourselves into a militia,” to “study the art of military with the utmost attention, view it as the science upon which your future security depends.”[3] The delegates were actively dismissing the perception that only the northern colonies were rebellious. Still, it would take active solidarity of the state’s citizens to fully dispel the myth of indifference or British loyalty. More specifically, it would take ardent leaders like Cornelius Harnett to reveal the patriotism of the southern colonies to British leadership.

In support of their sister colonies in the North, the coastal populace of North Carolina responded quickly and with great ardor in support of the delegation’s circular letter. More committees of safety, which were already present in the state, were formed, mustering militias and declaring a more direct opposition to the Crown and the actions of British soldiers in and around Boston. The most notable committee, constituted from the inhabitants around the mouth of the Cape Fear River on the southern coast, was the Wilmington Committee of Safety. With the coastal town of New Bern, North Carolina’s coastal region remained an active place for government and political activity. While the interior was seen as an inferior frontier, from Wilmington the first great men and actions in response to the outbreak of war would come.

Wilmington had a large population for the Old North State state, boasting roughly 1,200 residents with more citizens located in the surrounding countryside.[4] A port town, it maintained a wide network of trade, with a string of forts in and around the Atlantic coastline and the mouth of the Cape Fear River. It was here that the British Royal Governor, Josiah Martin, who replaced William Tryon after he was transitioned to New York, spent much of his time.

One November 23, 1774, Wilmington leaders held “a meeting of the freeholders in the court house at Wilmington, for the purpose of choosing a committee for said town, to carry more effectively into execution the resolves of the late [first continental] congress held at Philadelphia.”[5] The committee was to respond to the boycott on American goods and the Intolerable Acts passed by the British Parliament.[6] Among those selected was Cornelius Harnett. Harnett was a Chowan county born merchant, distiller, shipper, farmer, and miller who had been involved in politics since his 1750 election to the Wilmington Town Council.[7] As his political wisdom and influence grew, Harnett’s sentiments were “warmly attached to the cause of American Freedom” as tensions between Britain and North America intensified.[8]

Harnett was not alone. The Patriot sentiment was seen by the British leadership as weak or lacking. However, fellow patriots and North Carolinians rallied together, Harnett among them, to revolt. Among the colonial patriots were Robert Howe and John Ashe, both of whom had once held pro-British sentiments. Howe supported Governor Tryon, the British governor of North Carolina, in the 1771 Regulator movement, but as tensions grew he joined the Sons of Liberty in North Carolina and was appointed in 1773 to North Carolina’s Committee of Correspondence. In 1775 he commanded the Brunswick County militia as a colonel. Like Howe, John Ashe, brother of Samuel Ashe who was on the Wilmington Committee of Safety with Harnett, served the Patriot cause diligently. John Ashe was a French and Indian War veteran and student of Harvard University whose military experience benefited North Carolina as a colonel in 1775.[9]

The Committee of Safety was one of many representations of the Revolutionary sentiment in the Carolinas and southern colonies. Although the British did not anticipate the fervor they found in the North, they did undertake measures to intimate and dissuade actions against the crown. On July 7, 1775 the North Carolina Gazette, published from New Bern, ran a proclamation by Royal Governor Josiah Martin from June 26, issued from Ft. Johnston, that “endeavored to persuade, reduce, and intimidate the good People of this Province.” The editors resolved that “the dearest rights and privileges of America are at stake.” Importantly, the column closed by quoting the final lines of a British letter to a parliamentary representative in North Carolina from March 29, 1775, addressed to a Mr. Boyd: “His Excellency our Governor called a Council at Fort Johnston last Saturday, when it was resolved to prorogue the Assembly till the 12th of September next.”[10] The actions of the governor and statements of the North Carolina Gazette reveal the bellicose tension in the region. The powder was filling the keg. The place of Governor Martin’s proclamation, Fort Johnston, seemed just the place for it to blow.

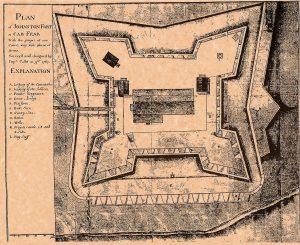

Construction of Fort Johnston had begun in 1745 under the leadership of Royal Governor Gabriel Johnston, whose name the Fort bore. The intention was to protect the mouth of the Cape Fear River south of Wilmington from non-British powers such as the Spanish. Fort Johnston was built on the western bank of Cape Fear River’s mouth looking out into the Atlantic Ocean from a protected position. Any ship moving upriver toward Wilmington would have to pass the fort on its port side. As the fort’s purpose waned it was increasingly neglected. After the French and Indian War, the need for the fort diminished almost entirely. In 1775, the result of inattention was a weak, nearly defenseless, shambled structure. In a governor’s council meeting Capt. John Collet, commander of the Fort, was quoted as having said that the Fort was, “in no state of defense . . . destitute of powder” with a garrison “consisting of 25 men only.”[11]Just one month later, a similar report was shared in another governor’s council. Instead of reinforcing the fort, the council received the word that it had only been further diminished. Capt. Collect was again quoted,

The Garrison of that place was reduced to no more than three or four men that he could depend upon, and that he had received advice of a considerable body of the People of the County being collecting in order to attack the place, he had thought it advisable for the preservation of His Majesty’s Artillery to dismount the Guns in the Fort and to lay them under the protection of the Guns of His Majesty’s Ship of War and to withdraw the little remnant of the Garrison the shot and small Stores and to place them in security on board a Vessel lying under the protection of the King’s Ship.[12]

The Fort was ripe for a symbolic attack which, while having no tactical value, would represent the opinions of the inhabitants of the colony of North Carolina. Because of this, British warships in the Cape Fear River were fully prepared to defend the coastal region no matter the state of the fort. Informing his superiors of his withdrawal from the fort, Governor Martin positioned his warship Cruizer to fight for the fort should it become necessary.[13]

On Saturday, July 15, 1775 the Wilmington Committee of Safety, under the leadership of Samuel Ashe and Cornelius Harnett, met and recorded the blunt statement, “that a reinforcement of as many men as will voluntarily turn out, be immediately dispatched to join Colonel Howe who is now on his way to [attack and burn] Fort Johnston.”[14] Howe led his second Brunswick County militia toward the empty Fort. Despite its lack of men and supplies, the committee and Colonel Howe concluded that if Captain Collett “should be suffered to remain in the Fort, . . . he might thereby have opportunity of carrying his iniquitous schemes into execution.” Reinforcements for Colonel Howe came quickly. A great many volunteers were immediately collected, a party of whom reached Brunswick, when they learned that the Collett had carried off “all the small arms, ammunition, and part of the Artillery.”[15]

The Wilmington Committee of Safety recorded the subsequent events in neutral tones: “about 500 men marched to the Fort, and burnt and destroyed all the Houses.”[16] Governor Martin, on the other hand, witnessed the drama of the fort’s destruction and recounted it with greater emotion. On the night of July 17 “a certain Captain Smith brought a letter on board this Deponent’s Ship [the British ship Unity] and having procured a light this Deponent read the contents and found the substance thereof to be, that Colonel Ashe requested the Masters and Commanders of the Ships at the Flatts to assist him with what Boats, Men and Swivel Guns they could spare, in the glorious cause of liberty, which letter was signed John Ashe.”[17] The letter to Governor Martin was from “The People” and laid out their rationale for their actions:

As the Establishment of Fort Johnston was intended to protect the Inhabitants of Cape Fear River from all invasions of a foreign Enemy in times of War . . . because with that we conceive the safety of this Province is intimately connected, with this intention we shall proceed to Fort Johnston and that our conduct may not be misunderstood by your Excellency we have thought proper to give you this information and persuade ourselves we shall not meet obstruction from any person or persons whatsoever in the execution of a design so essential to His Majesty’s Service and the Publick utility.[18]

Governor Martin expounded on the quickly unfolding events to Lord Dartmouth in a July 20 letter.

Awakened at 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning of July 19, the Royal Governor North Carolina stood on the deck of the Cruzier Sloop of War and watched while “Captain Collet’s house in Fort Johnston was on fire.” As for the fort, “wood burnt like tinders” and it was “entirely consumed.”[19] Governor Martin had no men to land and did not feel it necessary to fire upon the 500 volunteers and men under Robert Howe who had set fire to the fort.[20] The late-night show of force was not complete. At daylight Governor Martin saw some 300 men return to the Fort to “set fire to everything that had escaped the flames the preceding night.” The final fires were started in the afternoon, when John Collet’s “large barn, stable, and coach house” were set aflame. Martin called it “disgraceful to humanity.” Picking out the Revolutionaries, Martin was careful to acknowledge to Lord Dartmouth that, “Mr. John Ashe and Mr. Cornelius Harnett were ring leaders of this savage and audacious Mob, concerning which my present information enables me to add nothing furthur.”[21] North Carolina’s Samuel Adams had demonstrated that the southern colonies would have nothing less than their liberty and independence.

As Fort Johnston lay in charred rubble, both sides reeled at the cataclysmic events of the summer of 1775. Conclusions were drawn about the impact of the fort’s torching and how it should have affected the relationship between North Carolina and her British overlord. On July 28, just nine days after the burning, The Cape-Fear Mercury of Wilmington issued a statement from the New-Hanover and Wilmington Committee of Safety on the impact of the events of July 19: “Whereas it appeared, upon inconceivable evidence, that John Collett, commander of Fort Johnston, was preparing the said fort (under the auspicious of Governor Martin) for the reception of a promised reinforcement, which was to be employed in reducing the good people of this province.” The paper went on to print a resolution of thanks given to the inhabitants of North Carolina who were able to effect this public good. There was then a call for a provincial convention to meet on August 20, from orders of Samuel Johnston of the Continental Congress, all of it issued by the committee chair, Cornelius Harnett.[22]

One month later, on August 15, Governor Martin issued a proclamation from Cruzier in the coastal waters of the Cape Fear River near Fort Johnston’s ashes. His opening remarks acknowledged The Cape-Fear Mercury’s description of the July 19 events. The governor’s enraged spirit was evident, when he attacked the paper as sharing “incontestible facts” coupled with “scandalous Seditious and inflammatory falsehoods” that were “evidently calculated to impose upon and mislead the People of this Province and to alienate their affections from His Majesty and His Government.” Martin acknowledged that John Collet had drawn complaints of violence and misbehavior—however, he pointed out, “they were never addressed to me.”[23] Finally, Martin’s proclamation denied the motives set forth by The Cape-Fear Mercury, instead asserting that the Committee of Safety had incited local citizens who were

the most part strangers to all the ostensible motives to the outrages they were hurried on to commit and which according to the acknowledgement of this despicable seditious meeting had no better foundation than resentment to Captain Collet, an individual whose offences the Law’s power and that which I derive from His Majesty were competent to correct in a legal way.[24]

Johnston.

Martin indicated that he was unaware of the actions of Captain Collet and did not wish for oppression. But this very lack of knowledge is precisely what the colonists were rebelling against. They detested the distant reach and oversight of the crown’s authority. The foreign nature of government under British rule had led to abuses by the fort’s commander, and they would stand for it no longer. Governor Martin concluded with assertive language, “hereby declaring every such Election illegal, unconstitutional and null and void to all intents and purposes.” Then he ordered all of, “His Majesty’s Justices of the Peace, Sheriffs and other officers, and all other His Majesties liege Subjects to exert themselves in the discovery of all seditious Treasons and Traiterous Conspiracies, and in bringing to justice the principals and accomplices therein.”[25] Fort Johnston was burned by traitors, and the British would not stand for such rebellious. Harnett, Howe, and Ashe had set North Carolina on a war footing, ready to follow Samuel Adams and their northern brethren into the war.

The burning of Fort Johnston stood as a symbol of the war in the South. Although Governor Martin had removed the soldiers and supplies, the firing of the fort represented a show of force and the ideological break with Britain for the South. While the British falsely believed that the sentiment for Independence was northern alone, Patriot inhabitants of the Carolinas showed their ardor and support for their northern brethren and the cause of all the colonies. The spirit of liberty and these actions led by Cornelius Harnett were a show of force, independence, and an ultimate desire to break with the crown. North Carolina, led by Harnett, was revolutionary from the beginning.

[1]Journal of Josiah Quincy [Extract], March 26, 1773 – April 5, 1773, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0180.

[3]Circular Letter from William Hooper, Joseph Hewes, and Richard Casewell to the Inhabitants of North Carolina, June 19, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0011.

[4]Robert M. Dunkerly, “Overlooked Wilmington,” Journal of the American Revolution, August 28, 2016, allthingsliberty.com/2014/01/overlooked-wilmington/.

[5]Minutes of the Wilmington Committee of Safety, November 23, 1774, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0322.

[6]Office of the Historian, “Continental Congress 1776-1783,” U.S. Department of State (U.S. Department of State), history.state.gov/milestones/1776-1783/continental-congress.

[7]Donald R. Lennon, “Harnett, Cornelius, Jr..,” NCpedia (State Library of North Carolina, 1988), www.ncpedia.org/biography/harnett-cornelius-jr.

[8]Journal of Josiah Quincy [Extract], March 26, 1773 – April 5, 1773, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr09-0180.

[9]Richard Carney, “Robert Howe (1732-1786),” North Carolina History Project (John Locke Foundation, 2016), northcarolinahistory.org/encyclopedia/robert-howe-1732-1786/.

[10]The North-Carolina Gazette(Newbern), July 07, 1775, newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn84026629/1775-07-07/ed-1/seq-3/.

[11]Minutes of the North Carolina Governor’s Council, June 25, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0017.

[12]Minutes of the North Carolina Governor’s Council, July 18, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0052.

[13]Josiah Martin to William Legge, Earl of Dartmouth, July 16, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0045.

[14]Minutes of the Wilmington Committee of Safety, July 15, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0043.

[15]Minutes of the Wilmington Committee of Safety, July 20-21, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0055.

[17]Deposition of Samuel Cooper Concerning the Destruction of Fort Johnston, August 7, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0069.

[18]“the People” to Martin, July 16, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0048.

[19]Martin to Legge, July 20, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0053.

[20]Minutes of the Wilmington Committee of Safety, July 20-21, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0055.

[21]Martin to Legge, July 20, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina,docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0053.

[22]The Cape-Fear Mercury(Wilmington, N.C.), July 28, 1775, newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn83025834/1775-07-28/ed-1/seq-4/.

[23]“Proclamation by Josiah Martin concerning the election of delegates to the Provincial Congress of North Carolina and militia officers and loyalty to Great Britain,” August 15, 1775, Colonial and State Records of North Carolina, docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.php/document/csr10-0081.

One thought on “The Samuel Adams of North Carolina: Cornelius Harnett and the Burning of Fort Johnston”

Well done! Important history that needs to be remembered.