In the summer and fall of 1776, the decrepit fortifications at Ticonderoga and the area surrounding it became one of the top five population centers in North America—ultimately numbering 12,000 or more. In early July, a brigade under the command of New Hampshire’s John Stark began building fortifications on the forested, 300-acre rocky peninsula across the southern extension of Lake Champlain. First called Rattlesnake or East Hill, it briefly became known as Stark’s Point but, with the arrival of news of the Declaration of Independence, the name changed again to Mount Independence.

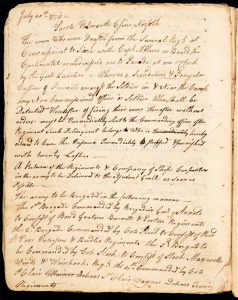

Mount Independence is now a Vermont state historic site.[1] Recently, the regional director of the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation, Elsa Gilbertson, sent this author a note about a document on the website of the New Hampshire Historical Society. The 146-page manuscript is part of the ‘General John Stark Papers, 1758-1819’ and is an orderly book for the brigade Stark commanded, which included his own 5th Continental Regiment. It covers mid-April to early September, 1776—the early months of the occupation of the Mount and Ticonderoga.

I contacted the society and asked if the book had been transcribed and published. A prompt reply from vice-president Joan Desmarais told me that it remained in the queue for that work to be done but it would not be finished before the end of the year. Not wanting to wait, I read the manuscript on-line and, as expected, found much interesting information.

To better appreciate the purpose of this manuscript, one must first understand the function of an orderly book. In the eighteenth century, a number of companies (typically, six to ten) of up to one-hundred men each made up a regiment, a handful of regiments formed a brigade, and an assembly of brigades formed a division or, as in this case, an army. Orders were issued at each level and filtered down to the lower echelon. An orderly book is the daily record of those orders issued to a particular brigade, regiment, or company. On a daily basis, whoever kept the book reported to the officer dispensing the orders and copied them into the book, before reporting the orders back to his commanding officer. At the company level, an orderly sergeant kept the book up to date and the orders were read to the men in the company.

While an orderly book may occasionally contain bits of commentary, it is not a personal diary and does not usually include the musings or observations of the writer. Rather, it is an official record of orders, declarations, and details on an extensive variety of official processes and happenings within the army.

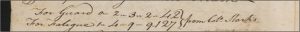

With few exceptions, the daily entries in this orderly book start with the orders from the overall headquarters. Those are followed with orders specific to Stark’s brigade, which regularly include the name of the officer of the day, the officer in charge of the fatigue party (the group clearing land, building fortifications, etc.), and the number of men designated regiments are to provide for the fatigue and guard details. Occasionally, a day’s entry includes orders for Stark’s 5th Continental Regiment.

There are gaps of a few days in the book. For example, Stark’s and five other regiments boarded ships at New York and headed for Canada on April 28.[2] The next entry is dated at Albany on May 9. No explanation for the lapse is given but it is likely that being stuck on ships minimized the need for daily orders and complicated the ability to share any. The usual routine resumed once the troops went ashore at Albany.

The entries are also missing for the days between May 17, when the unit was at the south end of Lake George and June 5 at Sorrell in Quebec. As above, this is a period when the troops were traversing the lakes so the daily routine had to have been considerably altered.

Another significant gap occurs between June 10, with the regiment still at Sorrell, and lasts until July 2, when they arrived back at Crown Point. As with the previous example, the regiment spent this time conducting a movement across Lake Champlain. Here, however, there is yet another factor to consider—the American army spent this time in a headlong retreat out of Canada, with the British army constantly pressuring them. Consequently, the routines of military procedure temporarily disintegrated under those conditions.

It is also possible that some pages may be missing. The book’s binding string is nearly all gone so the pages are loose and some might have disappeared in the intervening two-and-a-half centuries. This is definitely the case at the beginning, as the extant first page starts in the middle of a day’s entry. Lost pages do not account for the first and second gaps, however. With regard to the former, the entry at the start of the gap immediately precedes on the same page that for the resumption of entries. In the second case, the two entries are on opposite sides of the same piece of paper. No such simple answer exists for the third gap: the days at the beginning and end of the gap are on opposite pages and it is impossible to tell if intervening sheets are gone.

At least two people made entries into the book. That is not at all unusual as the duty of maintaining the book might fall on different people as time passed. It is likely that John Stark’s son, Caleb, kept the book for some of the time but further research into the regimental and brigade records is required to confirm.

An attentive reading of the book provides considerable information. Within the notations, a wide range of topics are addressed—promotions; brigade assignments; courts-martial and their findings; clothing (or the lack of); ammunition; tentage; digging of vaults (latrines); requests for tailors, sailors, and both building and ship carpenters; chaplaincy; tools (particularly axes—there are several mentions of clearing ground on Mount Independence); engineers; cooking; men drafted to serve as marines on the fleet; sutlers and their prices; liquor; soap; . . . the list goes on.

Some entries provide very specific details for the researcher. For example, brigade orders for April 14 in New York include the following:

The following Alarm Posts are assegned to the Regts; in this Brigade Vizt—Reeds Patterson’s and Poor’s RegtsWithin the Lines at the Grand Battery and are to march On to their Alarm Posts in the following manner Vizt—Colo: Poor’s Regt: to pass by the Guard House, and man the Right of the Battery, Colo: Patterson’s to enter on the left of the Battery and man the Centre, Colo: Reed’s to enter at and man the left of the Battery, Colo: Stark’s to man the Fort—with four Companies, the other four to be Stationed at the following places at the works in Beaver lan[e] 1 Compy: at Thames Street Little Queen Street, Cortlandt Street, Dey Street and Partition Street one half Company each—Colo: Nixon to Man the works hereafter mentioned With No. of M following Vizt: Beekmans Slip, Burling Slip, Murry’s Docks, Old Slip Market, the Barrier Near his Quarters, and the works at the Royal Exchange With one Company each, and the Works at Fly Market With two Companies All the Men to be at their Alarm Posts tomorrow morning at 6 oClock, all the Officers Are desired to be Present—[3]

There are entries in the text which lend themselves to reasonable inference. One order is concerned with changing the time in the evening when the countersign was required.[4] The order includes the statement, “there is no distinguishing Citizen from Soldiers.” From those few words, it is clear that the soldiers did not have uniforms.

By the time this book was created, people had come to realize the war would not be over quickly. The American army had yet to organize itself into a true military force, with discipline a central issue. Details within a few orders describe some of the disciplinary problems within the young army including examples of “Pillaging & Marauding” of private property. While not a common entry, they do hint at a lack of respect on the part ofsome soldiers for the private citizen. As one order comments, “this Army is Paid to Protect not Pilfer the Inhabitants.”

Another example details soldiers’ abuse of wagoners and bateaumen. As citizens who contracted with the army, several ended up quitting the service due to these negative interactions. The orders that resulted explained that the abuse, “whilst it reflects disgrace on our Arms, may be attended with the most fatal consequences to our righteous cause and to the Army rais’d for its support.” Without these contractors, supplies could not be moved with potentially catastrophic results. Already faced with a shortage of supplies and the bateaus and carriages to move them, inciting the operators to quit exacerbated the problem significantly.

On more than one occasion, orders similar to the following can be found: “The Riotous and disorderly behavior of some of the Troops obliges the Genlto order every Soldier to be at his Barrack at 9 o’Clock—The Several Guards are directed to take up & Confine any Soldier found Strolling thro’ the City [Albany, in this instance] after that time—The Tattoo to beat precisely at nine o’Clock”[5]

Those caught committing violations risked a court-martial and there are several entries creating and dissolving courts. The findings, but not the detailed proceedings of the trials, are included and and the text conveys a fascinating breadth of the various crimes of which soldiers and officers were accused. The outcomes range from whipping (often thirty-nine lashes) to execution if guilty and acquittal with honor if not guilty. There are no mentions of soldiers being brought up on charges for seemingly minor offenses such as “strolling thro’ the streets.” Enforcement of these violations may have been handled at the company level.

Other indications the troops’ behavior can be found throughout the manuscript. On three separate days, there are orders against the men putting their packs in bateaux and carriages—conveyances reserved for supplies and the army’s heavy baggage. Orders can also be found telling officers to inspect tents and ensure that any boards used for flooring in them did not get damaged.

Several entries deal with the health of the troops; small pox was of particular concern. Orders were issued to quarantined infected soldiers from the rest of the camp and when large numbers of militia began to arrive, the garrison received orders to wash themselves and their clothes and to wash and smoke their tents ahead of time. The reinforcements remained in their own camp for a few days before being brigaded with the rest of the army. Interestingly, the issuance of soap is noted more than any other item.

The effort to develop a professional fighting force became increasingly pronounced in early July, once the army was back at Crown Point, and then Mount Independence and Ticonderoga. Orders were issued for the men to drill for an hour and a half, twice a day. In earlier entries, the parole and countersign seldom appear in the book but, beginning in July, all but a small handful of days include those terms. For better or worse, the number of courts-martial also increased at this time. An occasional entry explains one motivation for these efforts—the fear of an attack by the British.

This article offers just a small sample of what is contained in this orderly book. Should you wish to read it yourself, high-quality scans of all 146 of the original pages are available online. The manuscript pages are easy to read for the most part and each page can be magnified and rotated. This latter feature is quite handy, because whoever scanned the book did it backwards and up-side down. To read it in chronological order, you have to start at scan 146 and work backwards. No matter the order, you have to rotate every page one-hundred-eighty degrees. In spite of that, anyone with an interest in details of army life in the Revolution will be rewarded for their effort.

[1]“State Historic Sites,” Agency of Commerce and Development, The State of Vermont, last modified April 2022, historicsites.vermont.gov/.

[2]The order includes the names of several ships, their captains, and the number of men to ship aboard each one.

[3]“Orderly Book, April-September 1776,” John Stark Papers, The New Hampshire Historical Society, www.nhhistory.org/object/276884/orderly-book-april—september-1776.

[4]A guard would challenge someone approaching him by giving the parole. That person would be required to give the countersign. Anyone who could not would be suspect.

[5]The tattoo was the signal for all soldiers to be in their quarters. Only those on duty or with permission could be out and about after tattoo.

Recent Articles

The 1779 Invasion of Iroquoia: Scorched Earth as Described by Continental Soldiers

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...