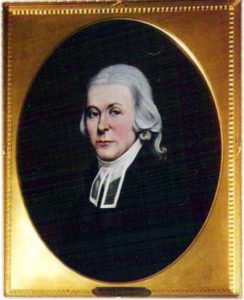

Rev. George Whitefield (1714-1770) was an ordained Church of England priest with an exceptional speaking voice who in his lifetime swayed countless people towards historic Christianity. In a time of the liberalization of historic Protestant Christianity, Whitefield preached the simple biblical message of the Protestant Reformation, that people could not reach God or merit God’s favor by their own efforts. Religious sincerity, ecclesiastical rituals, and pious self-sacrifice, Whitefield believed, could never earn heaven. Instead, he advocated for the new birth in Christ as the way of salvation. His message was not popular within his own Church of England, but colonists in America, many of whom dissented from that church, flocked to hear him preach by the tens of thousands.[1]

George Whitefield and Religious-Political Liberty in America

Stirrings of revival and awakenings were already present when George Whitefield arrived in the American colonies in 1739. Whitefield was a unifying factor in a colonies-wide awakening that helped the separate colonies come together as one nation.

In the eighteenth century, English kings downplayed religious liberty in favor of a government-sponsored church to support a unified administration, with the king as sovereign. Congregational, Presbyterian, Baptist, and all other separatist or independent groups were often considered disloyal to England and in rebellion to God. The Church of England was dependent upon secular, political support to survive. Most colonists in New England were from independent or dissenting ecclesiastical backgrounds. Their autonomous colonial churches, whether Quaker, Congregational, Baptist, or Presbyterian in polity, were under the general authority of the King of England, yet not supportive of the Church of England. There was no unity between the distinct independent denominations in America until George Whitefield united them through his incessant travels in support of the Great Awakening.[2] One could not have anticipated that this colonial unity would lead to a war of independence from the mother country.

Whitefield preached within the walls of church buildings and in the outdoors. From 1740 to his death in 1770, he may have been the most well-known English-speaking person in America. During his 1739-1741 and 1744-1745 preaching tours, Whitefield was the human instrument in a huge inter-colonial revival. He made several more visits to the colonies before he died.[3]

Whitefield’s influence on the thoughts and ideas of American colonists was significant. He taught them the value of independent thought apart from ecclesiastical control, and instructed his followers on the primary importance of an individual’s relationship to God. The effect of this new thinking on religious liberty in Christ loosened the colonists from dependence on Great Britain in ecclesiastical matters. In a period when there were not sharp distinctions between the sacred and the secular, ecclesiastical independence laid a foundation for economic and political independence.[4] Colonists who had no confidence in the Church of England naturally had no confidence in the head of the Church of England, King George III. Independence from the mother country in religious affairs quickly transferred to ideas of political independence as tensions between the colonies and Britain intensified.[5] Whitefield’s preaching and theology influenced many military chaplains in the American Revolution.[6]

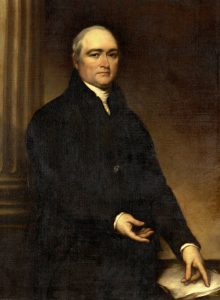

Rev. Hezekiah Smith (1737-1805) of Haverhill, Massachusetts was a respected Baptist pastor. He was born in Long Island, New York and educated at Princeton at a time when Whitefield was welcome on the campus. Smith followed Whitefield’s example of itinerant evangelism and was widely accepted by supporters of revival. In 1764, Smith preached in New England and briefly settled in a Congregational church Haverhill, Massachusetts. The First Baptist Church in Haverhill was founded in 1765, where Smith remained the pastor until his death forty years later, interrupted only was when he did itinerant preaching and when he served as an army chaplain.

Smith was born as the Great Awakening was spreading through New England, and grew up in a household that supported the revivals.[7] After graduating from Princeton in 1762, his itinerant preaching often took him to the southern colonies. In the 1760s, Smith preached several times at Whitefield’s orphanage in the Savannah, Georgia area. Smith was affectionately called “a second Whitefield.”[8] In February 1770, he preached at the orphanage and shared at least two meals with Whitefield.[9] That September, as the itinerant Whitefield travelled and preached in Massachusetts, Smith tried to go hear him preach but their schedules did not match. Smith wrote, “Went as far as Byfield in order to see Mr. Whitefield but was disappointed.”[10] Apparently, Whitefield had agreed to preach for Smith in Haverhill in October, but died a few weeks before.[11]

Smith transferred his theology of freedom in Christ and liberty of conscience, to freedom and independence in civil and political concerns. Whitefield and the Great Awakening caused Smith to evaluate his world through the eyes of religious individualism and self-sufficiency.[12] To him, direct access to God through Christ made the petty claims of British tyrants across the ocean irrelevant, even ridiculous. When war broke, Smith volunteered as chaplain to the 4th Continental Regiment, served as a brigade chaplain, and occasionally was an aide-de-camp.[13] He served in and around New York City and the Hudson River area as well as in New Jersey and Pennsylvania.[14] Smith was a confidant of Gen. George Washington and other senior leaders.[15]

Chaplain Smith’s journal has many notations showing his evangelistic and morale enhancing activities among troops in the field. He saw his service to his country, and the salvation of the souls of the troops, as the same mission. In March 1776, Smith was asked by his commander and his troops to extend his tour of duty. He agreed, writing that the “cause of our country, joined with that of usefulness of souls, inclines me to yield to their request.”[16] He endured the severe winter encampment at Valley Forge in 1777-1778. Under General Washington’s orders, Smith was made commander of a large detachment of sick and wounded troops. A biographer of Smith wrote, “Mr. Smith was a great admirer of Whitefield, whom in some respects he imitated.”[17] In 1780, Hezekiah Smith returned to the First Baptist Church in Haverhill, successfully serving there until his death in 1805.

Rev. Samuel Spring (1746-1819) was thirty years old when he volunteered as a chaplain. He was the son of a successful farmer in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, where his minister was Rev. Nathan Webb, such an outspoken advocate of Whitefield that he signed the 1743 Testimony in support of Whitefield and the Great Awakening.[18] Spring’s father was a deacon in Webb’s Congregational church. Sensing a call to ministry, Spring did college preparation studies with Webb before he attended college in Princeton, New Jersey, at that time an evangelical Christian school. We do not know if Spring heard Whitefield preach while he was a student. After graduating in 1771, Spring continued his theological studies and was licensed to preach in 1774.[19] His preparation for ministry was distinctly evangelical, greatly influenced by the legacy of George Whitefield.

In April 1775, Samuel Spring quickly volunteered to be a continental army chaplain. That summer he was chaplain to the American troops that invaded Canada. Spring shared in all the hardships of the troops, and quickly won their respect. The journey to capture Quebec was a disaster. The men were cold, hungry, exhausted, and poorly supplied. Spring counselled and prayed with the men, buried the dead, encouraged the troops and leaders, and held church services. When Sundays came, men piled their knapsacks into a makeshift pulpit that an assistant helped Chaplain Spring mount to preach in the open fields.[20] The message of salvation through Jesus Christ was a common theme in his preaching, as he earned the favor of officers and troops.[21]

Chaplain Spring was part of the New Year’s Eve attack on Quebec city. He assisted the severely wounded Col. Benedict Arnold on the battlefield, then transported him back to a hospital. After months of living in filth and crude army encampments, the Americans retreated. Many were sick, as was Chaplain Spring. Towards the end of 1776, Spring departed the army and settled into a church in Newburyport, Massachusetts.[22]

The affection Chaplain Samuel Spring had for George Whitefield was demonstrated as his unit prepared to depart from Newburyport for the march through the wilderness to Quebec. Spring had commanders assemble the troops in the Old South Presbyterian Church pastored by staunch Whitefield ally Rev. Jonathan Parsons. Whitefield had preached dozens of times from this pulpit, and was buried in a crypt in the basement. Whitefield’s body lay beneath the feet of the troops as Chaplain Spring preached in 1775. In Spring’s own words,

On the Sabbath morning the officers and as many of the soldiers as could be crowded onto the floor of the house, were marched into the Presbyterian Church in Federal Street. They marched in with colors flying, and drums beating, and formed two lines, through which I passed—they presented arms and the drums rolling until I was seated in the pulpit. Then the soldiers stacked their arms all over the aisles, and I preached to the army and to the citizens, who crowded the galleries, from this text: “If thy spirit go not with us, carry us not up hence.”[23]

Spring preached to the standing-room-only crowd of troops, with civilians packed in the upper galleries. The senior officers asked if it was appropriate to visit the basement tomb of Whitefield. As the chaplain, Colonel Arnold, and others stared at the dusty remains of Whitefield, they cut away portions of his clothing as keepsakes and stood over the corpse “with solemn awe and reverence.”[24] After his army chaplaincy, Rev. Samuel Spring married, had a large family, and served the Presbyterian church in Newburyport until his death in 1819.

Chaplain Ebenezer David (1740-1778) of Newport, Rhode Island had a brief but interesting military experience. His father, Enoch David, so admired Whitefield that the two travelled together for weeks at a time doing itinerant evangelism.[25] Before coming to Rhode Island, Ebenezer David was a student at the Philadelphia Academy in Pennsylvania, an institution founded with significant influence from Whitefield. He then attended Rhode Island College (later Brown University), another institution influenced by Whitefield, and was baptized at the age of thirty while a student, around the time Whitefield was traveling and preaching in the area.[26] As a Baptist, David had differences with Whitefield over infant baptism, but overlooked these based on their unified evangelical faith.

While a student in Rhode Island, David spent weekends and school vacations in Newport with members from the Seventh Day Baptist Church.[27] His college graduation ceremony in 1772 was held at the large Beneficent Congregational Church in Providence.[28] After he graduated, David taught college preparatory courses and did itinerant preaching. The Seventh Day Baptist Church licensed him to preach in 1773, after which he began an itinerant evangelistic ministry in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania.[29] Clearly the influence of George Whitefield was on this man. The Seventh Day Baptist Church, the oldest congregation of this denomination in America, ordained Ebenezer David in 1775. David ministered in a meetinghouse constructed in 1729.[30]

The religious zeal of Rev. Ebenezer David easily transferred to the cause of religious and political freedom. In 1776 he became one of the first chaplains commissioned in the Continental Army, serving with the 9th Continental Infantry in the siege of Boston and the New York campaign. He again served from 1777-1778 with the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment, wintering in 1777-1778 with General Washington and the freezing troops at Valley Forge. Due to the poor treatment of the wounded, and the sicknesses and diseases in the camps, David thought he could help by transferring to be a medical officer.[31] Because of his declining health he was discharged from the military in 1778, and he died shortly thereafter.

Rev. Timothy Dwight IV (1752-1817) was one of the fifty-one continental army chaplains known to have resided in Connecticut. He was born on May 15, 1752, in Northampton, Massachusetts. His father was successful merchant and farmer Timothy Dwight III, his mother was Mary Edwards, third daughter of famous pastor and theologian Rev. Jonathan Edwards. They married five months after Jonathan Edwards was forced out of his Northampton ministry. Since Jonathan Edwards died in 1758, his grandson Timothy may have had only a few memories of his influential grandfather, but he learned all about the man’s revivalist theology from his mother.[32] Timothy Dwight was raised in a home where memories of the Great Awakening under Jonathan Edwards and George Whitefield were appreciated. When Mary was six years old, Whitefield spent time in the Edwards home. On October 19, 1740, Whitefield wrote in his Journal that he was impressed with the orderly Edwards household, and with Mary and her siblings in their “Christian simplicity.”[33]

After two decades of controversy, in 1764 George Whitefield and Yale College had reconciled their differences, and the itinerant evangelist was welcomed to preach that year at Yale.[34] Timothy Dwight, after schooling at home, enrolled at Yale and graduated in 1769; as with his home, he attended a college where the name of Whitefield was respected. He stayed in New Haven as a grammar school teacher and then a rector at Yale College.

Dwight was licensed to preach in 1777, and shortly thereafter was appointed by the Continental Congress as a chaplain with Connecticut’s Continental Brigade. Chaplain Dwight served with distinction as his troops skirmished and performed raids in New York and Connecticut. Dwight was a confidant of General Washington, and his chaplain ministries during the war were lauded.[35]

Chaplain Dwight preached as a passionate, biblical speaker who caught the attention of men of all ranks. George Whitefield was a model of ministry for Dwight, as they were like-minded Calvinists that preached election, while being aggressively evangelistic.[36] Some have seen Dwight’s ministry as a reflection of his grandfather, Jonathan Edwards, and Whitefield.[37] An unnamed colonial army general said of Dwight’s knowledge of the Bible, “Well, there is everything in that book, and Dwight knows just where to lay his finger on it.”[38] Dwight was stationed at West Point, New York when news of the death of his father forced him to resign his chaplaincy and return home.

After the war, men like Timothy Dwight understood that just as God had granted them freedom in Christ, so God was the granter of victory and independence. He applied his revivalist faith to help build the fledgling nation.[39] His first post-war experiences were as a pastor of churches in Massachusetts and Connecticut. In 1795, he was appointed president of Yale College. Soon after, a series of extended revivals swept through the campus and surrounding community, affecting hundreds of students. Extended church meetings were held, prayer groups were formed, and many repented and made professions of faith. It appeared that the Great Awakening under Whitefield from the 1740s had returned to campus. Dwight encouraged and led these revival meetings at Yale, building upon the reputation and methods of Whitefield.[40] One author stated that George Whitefield, Jonathan Edwards, and Timothy Dwight were all from “The Revivalist School” of Calvinistic Puritans of like faith and practice.[41] From his childhood, through his army chaplaincy, to his post- war ministries, Timothy Dwight admired and respected the legacy of George Whitefield. Not one to separate the secular from the sacred, Dwight saw his preaching in spiritual matters as a key to the development of the new nation.

Rev. Samuel Bird (1724-1784) was a student at Harvard College when George Whitefield first travelled through Massachusetts in 1740. We do not know if Bird was already an advocate of the Great Awakening before his college days, but all Massachusetts was disturbed by Whitefield’s itinerant preaching. Harvard College was shaken with revival, and one Harvard student supporting Whitefield and the revival was Samuel Bird.

Born in Dorchester, Massachusetts in 1724, Samuel Bird was raised in a comfortable middle-class home. His father owned a wharf and was at various times employed as a constable, a selectman, and an assessor. Bird enrolled at the nearby Harvard College, perhaps in preparation for the ministry. He was in the class of 1744, but did not graduate – he was expelled because of his pro-Whitefield ideas.[42] For a few years, Bird was a minor player in the ecclesiastical disputes that overtook New England. We do not know for how long Samuel Bird preached in the Nashua, New Hampshire and Dunstable, Massachusetts area before he was called to be minister of the local Congregational church in 1747. Of his time in Nashua and Dunstable it was stated, “He was an ardent follower of Whitefield.”[43]

In 1751, Bird departed Dunstable for a ministry in New Haven, Connecticut. He married a Connecticut woman and began his ministry at a recently formed congregation, what was later called the North Church in New Haven. The official history of the North Church states,

Rev. Samuel Bird, came from Dunstable, Mass., and was installed October 15, 1751. . . . Mr. Bird was twenty-seven years of age at the time of his settlement, very evangelical, impressive, popular, and successful. During the sixteen years of his ministry the church became the largest in the town, containing 302 members.[44]

After sixteen years Bird resigned due to poor health.[45] He stayed with his wife and family in New Haven as he did part-time political and ministerial work.[46] When war broke out he volunteered to be an army chaplain.

The pro-Whitefield, revivalist ministry of Samuel Bird transferred from his civilian church ministries to his ministries as a colonial army chaplain. He was assigned to the 7th Connecticut Provincial Regiment from April to December 1775.[47] The regiment was raised in Fairfield, Litchfield, and New Haven counties. The regiment served mostly in Connecticut, securing port facilities, patrolling the coast, guarding bridges, and providing supplies for the continental army. On September 14, the regiment was ordered to Boston where British troops were surrounded by colonial forces.[48] His time as an army chaplain ended upon completion of his term of service.

Rev. John Cleveland (1722-1799) was a New Light leader born out of the Great Awakening of the early 1740s. He came to prominence from his conflict with the administration of Yale College, where he was a student. Cleveland heard George Whitefield preach at Yale and was fully supportive. After refusing to repent for attending a New Light meeting, Cleveland was expelled in 1745. Thereafter he served at a newly established church in the maritime Chebacco community of Ipswich, Massachusetts, also known as the Fourth Church in Ipswich.[49] He was ordained there in 1747.

John Cleveland successfully served as a pro-Whitefield, New Light pastor in the riverfront Chebacco-Ipswich shipbuilding community. Under his ministry the church had several periods of revival, as hundreds in and around the community experienced religious conversion. During Whitefield’s itinerant preaching from the 1740s to 1770, he was frequently a guest in the Cleveland home. Mary Cleveland, wife of Rev. John Cleveland, had fond recollections of Whitefield’s visit in 1754:

The Rev. Mr. Whitefield came to our house and preached the next morning in Mr. Cleveland’s meeting house and went to (the common) and preached two times and came and lodged with us that night. I think it is a great honor to have his company.[50]

For ministers like John Cleveland, freedom in Christ meant direct access to God without ecclesiastical or political interference. In his world, God was the center of everything. Through the new birth, a person had religious autonomy. In a world where there was a blending of the sacred and the secular, ecclesiastical sovereignty meant spiritual and practical independence. Church and politics were not separate, and religious self-reliance against the Church of England easily transferred to political antagonism against what were seen as intrusive and unfair British laws. In the fall of 1768, John Cleveland wrote his first political essay for the newly founded Essex Gazette newspaper. His theme was in protest of increasing taxation without proper legal representation. He stated,

Is it not the birthright of Englishmen to be free? Can they be free if they are taxed, to raise a revenue, without their consent? . . . Is there here not a such thing belonging to Englishmen as property? Can one man dispose of the property of another without his consent and not be guilty of robbery?[51]

John Cleveland is a clear example of a New Light devotee of Whitefield who was an ardent patriot in the cause of independence. From rural Chebacco, he wrote numerous articles and preached many sermons on Christian religious and civil liberty. In an open letter in the Essex Gazette, Cleveland asked, shortly after the battles of Lexington and Concord,

Is the time come, the fatal era commenced, for you to be deemed rebels, by the Parliament of Great Britain? Rebels! Wherein? Why, for asserting that the rights of men, the rights of an Englishman belong to us. . . . O my dear New England, hear thou the alarm of war! The call of Heaven is to arms! To arms! . . . Behold what all New England must expect to feel, if we don’t cut off and make a final end of those British sons of violence, and of every base Tory among us . . . We are, my brethren, in a good cause; and if God be for us, we need not fear what man can do … O thou righteous judge of all the earth, awake for our help. Amen and amen.[52]

John Cleveland witnessed men from his Chebacco church enthusiastically enlist in the military in the war for liberty. Under rising military and political pressure from Great Britain, Cleveland reminded Essex Gazette reader of the right to fight to maintain the Puritan ideals of New England’s founding fathers.

What shall we do to save ourselves from the distresses brought upon us by an untoward generation? I answer, be not cast down, O America! Be not discouraged, O Boston! . . . Let all ranks and orders of men reform from every immorality and vicious practice, and pray to the God of Heaven and Earth, the preserver of men . . . to break every weapon formed and forming against us,—to maintain our rights and privileges, civil and religious; and above all things, to make us a holy and truly virtuous people, and to preserve us pure from the growing pollutions in the world. [53]

In 1775, John Cleveland applied his New Light theology of freedom and independence to military service. He had served in the French and Indian War as a colonial militia chaplain. In the Revolutionary War, so the story goes, “He preached all the young men among his people into the army and then went himself, taking his four sons with him.”[54]

While still at his church, he wrote a charter for the local militia company, then joined it. In 1775, when news of bloodshed from the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord reached Ipswich, Rev. Cleveland and the local militia quickly rode several hours on horseback to the scene, but arrived too late. By the summer of 1776, almost three-fourths of the military-age men in Chebacco-Ipswich were part of the war effort. Cleveland was an army chaplain to men who mostly came from his own parish. This militia company saw action at the Battle of Bunker Hill, with one man wounded and one man killed. Later in 1775, Chaplain John Cleveland was assigned to the Massachusetts 17th Infantry Regiment. In the fall of 1776, Cleveland was again serving as a colonial army chaplain with a local Essex County regiment. They served under General Washington in Long Island and White Plains, New York. As the theater of war shifted south, Cleveland returned to his civilian ministry.[55]

Chaplain Cleveland disliked soldiers’ “profane swearing . . . gaming, robbery, and thievery.”[56] He preached to the troops, counselled, prayed with soldiers, buried the dead, and endured hardships from life in the field. In true Whitefield fashion, Cleveland opposed the theology of Unitarianism that spread through the ranks, believing it to be contrary to the Bible.[57] And Chaplain Cleveland insisted that the sabbath be observed on Sundays, a habit that was widely accepted during the war.[58]

John Cleveland returned to Ipswich and ministered in the area until his death in 1779.

Conclusion

Many other colonial clergymen who supported George Whitefield fought for independence from Great Britain.[59] Simply put, Whitefield’s influence upon colonists in the Revolutionary War was profound.[60] The religious culture in New England was more significant than in other American colonies, since many of the original settlers came to the New World to escape religious persecution.[61] Whitefield reminded them of what he considered to be their glorious religious heritage. Political interference by Great Britain upon the American colonies was seen as an infringement upon their freedoms to worship and live as free citizens.

Throughout his incessant travels in the colonies, George Whitefield unintentionally helped to create a new American nation. His preaching on the freedom to approach God without political or ecclesiastical permissions helped create a mindset of civil freedom away from Great Britain. It was during the revivals of the Great Awakening that American colonists began to view themselves as capable of interpreting the way and will of God for themselves.[62] Pro-Whitefield civilian clergy eagerly became chaplains in the cause of liberty. American religious scholar Thomas Kidd called Whitefield, “America’s Spiritual Founding Father.” Stephen Mansfield identified Whitefield as a “Forgotten Founding Father.”[63] Jerome D. Mahaffey asserted that Whitefield and his followers were directly responsible for the founding of the United States.[64]

The Great Awakening was a religious movement with significant civil and political implications. Here was an integrated, mass movement in America, creating a common, independent identity against the ceremonies, liturgies, and political interferences from England. Many preachers emphasized democratic ideas such as all people having equal standing in the sight of God and that they should not be ruled by political kings or religious bishops.[65] This was classic Whitefield preaching and theology. It was as if Whitefield and other clergy weaved people from various religious denominations, and even some of the irreligious, into a spiritual body of independent, freedom-loving thinkers that would withstand a war with Great Britain.[66] After praising Whitefield and other New Light preachers, historian Mouheb succinctly stated, “The colonists were strengthened for the American Revolution by experiencing spiritual liberty in Christ which caused them to stand up for political liberty.”[67] It may be an overstatement to say that without the Great Awakening there would not have been an American Revolution. Yet the influence of George Whitefield and the religious revival was a significant contributing factor in raising troops and chaplains for the American colonial fight for freedom.[68]

[1] There are numerous biographies of George Whitefield, of various quality. Three extend to two volumes and are very thorough: Luke Tyerman, The Life of George Whitefield (New York: Anson D.F. Randolph & Company, 1877); E.A. Johnston, George Whitefield: A Definitive Biography (Stoke-on-Trent, United Kingdom: Tentmaker Publications, 2008); and Arnold Dallimore, George Whitefield: The Life and Times of the Great Evangelist of the Eighteenth Century Revival (Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth Trust, 1979).

[2] Joseph Tracy, The Great Awakening: A History of the Revival of Religion in the Time of Edwards and Whitefield (1842: reprinted by Arcadia Press, Mt. Pleasant, SC, 2019). For regional studies of the Great Awakening, see Edwin S. Gaustad, The Great Awakening in New England (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith Publishers, 1965); Charles H. Maxson, The Great Awakening in the Middle Colonies (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1920); Wesley M. Gewehr, The Great Awakening in Virginia, 1740-1790 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1930). To review select original sources, see Richard L. Bushman, The Great Awakening: Documents on the Revival of Religion, 1740-1745 (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1969).

[3] Lee Gatiss, “George Whitefield—The Anglican Evangelist,” Southern Baptist Journal of Theology, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Summer 2014), 71-81. Peter Y. Choi, George Whitefield: Evangelist for God and Empire (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdman’s Publishers, 2018), 103-109.

[4] Choi, George Whitefield: Evangelist for God and Empire, 234.

[5] Bernard Bailyn, The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967). Alice M. Baldwin, The New England Clergy and the American Revolution (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1928). Peter N. Carroll, ed., Religion and the Coming of the American Revolution (Waltham, MA: Ginn & Company, 1970). Nathan Hatch, The Sacred Cause of Liberty (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1962).

[6] Jack D. Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War: Black Robed American Warriors (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company Publishers, 2017). Joel T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution (1861: reprinted by Solid Ground Christian Books, Birmingham, AL: 2005).

[7] John D. Broome, The Life, Ministry, and Journals of Hezekiah Smith, Pastor of the First Baptist Church of Haverhill, Massachusetts 1765 to 1805 and Chaplain in the American Revolution 1775 to 1780 (Springfield, MO: Particular Baptist Press, 2004), 6-7.

[8] Ibid., 18-19, 22, 41.

[9] Hezekiah Smith, The Journals of Hezekiah Smith (1805: reprinted by Particular Baptist Press, Springfield, MO: 2004), 358-359. Broome, The Life, Ministry, and Journals of Hezekiah Smith, 108-109.

[10] Smith, The Journals of Hezekiah Smith, 369.

[11] Broome, The Life, Ministry, and Journals of Hezekiah Smith, 154.

[12] Smith, “Commemorative Sermon Preached on the Second Anniversary of Burgoyne’s Surrender, October 17, 1779,” Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 283-288.

[13] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 249, 262, 267.

[14] Reuben A. Guild, Chaplain Smith and the Baptists (Philadelphia: American Baptist Publication Society, 1885), 5.

[15] “Hezekiah Smith,” Baptist History Homepage, baptisthistoryhomepage.com/smith.hezekiah.bio.html.

[16] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 164.

[17] Guild, Chaplain Smith and the Baptists, 138.

[18] The Testimony and Advice of an Assembly of Pastors of Churches in New England, at a Meeting in Boston, July 7, 1743, Occasioned by the Late and Happy Revival of Religion in Many Parts of the Land (Boston, MA: 1743).

[19] Joel T. Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution (1861: reprinted by Solid Ground Christian Books, Birmingham, AL: 2005), 90.

[20] Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 131.

[21] Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution, 96.

[22] Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 132.

[23] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 122.

[24] Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution, 93.

[25] Ebenezer David, A Rhode Island Chaplain in the Revolution: Letters of Ebenezer David to Nicholas Brown, 1775-1778 (Providence, RI: The Rhode Island Society of the Cincinnati, 1949), xvi.

[26] James N. Arnold, Rhode Island Vital Extracts, 1636-1899 (Providence, RI: 1900), 7:628.

[27] Whitefield had a significant influence on Baptists throughout the American colonies. Baptists with a Reformed or Calvinistic theology readily embraced Whitefield, including the Seventh Day Baptist Church in Newport. See Charles K. Adams, Universal Cyclopedia and Atlas (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1903), 1:492. Michael A.G. Haykin, George Whitefield (Grand Rapids, MI: EP Books, 2014), 105-121.

[28] Rev. Joseph Snow, Jr. was minister at the Beneficent Congregational Church from 1743 to 1793. He was a firm Whitefield supporter.

[29] David, A Rhode Island Chaplain, xxi-xxii.

[30] History of Newport County, Rhode Island; from the year 1638 to the Year 1887 (New York: L.E. Preston & Co., 1888), 440-441.

[31] Thompson, From its European Antecedents to 1791, 108, 119, 140, 155-156. Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 97, 154,

[32] Harry S. Stout, ed., “Dwight, Mary Edwards,” The Jonathan Edwards Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans Publishing, 2017), 160.

[33] George Whitefield, Journals of George Whitefield (1756: reprinted by Banner of Truth Trust, Carlisle, PA, 1985), 477.

[34] Roberta B. Mouheb, Yale Under God: Roots and Fruits (Maitland, FL: Xulon Press, 2012), 58. Dallimore, George Whitefield, 2:433.

[35] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 176, 205.

[36] G. Wright Doyle, Christianity in America: Triumph and Tragedy (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2013), 165.

[37] Alice B. Kehoe, Militant Christianity: An Anthropological History (New York: Palgrave Macmillan Publishers, 2012), 61.

[38] Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 64.

[39] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 215.

[40] Chauncey A. Goodrich, “A History of Revivals of Religion at Yale College from its Commencement to the Present Time,” American Quarterly Register Vol. 10, No. 3 (1838), 289-310.

[41] Lars P. Qualben, A History of the Christian Church (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2008), 471.

[42] “Rev. Samuel Bird,” www.findagrave.com/memorial/8940406/samuel-bird. For a broader view of Harvard and the Great Awakening, see George J. Gatgounis, “How did Harvard College Respond to the Great Awakening?” The Christian Observer, March 2, 2014, christianobserver.org/how-did-harvard-college-respond-to-the-great-awakening/.

[43] John H. Goodale, History of Hillsborough, New Hampshire (Philadelphia, PA: J.W. Lewis & Company, 1885), www.nh.searchroots.com/documents/Hillsborough/History_Nashua_NH_7.txt .

[44] Manual of the North Church in New Haven, May 1742 – May 1867 (New Haven, CT: E. Hayes, Printer, 1867), v.

[45] Hartford Courant, January 18, 1768.

[46] Rev. Samuel Bird represented the First Parish in New Haven for the 1774 Connecticut Congress. See Hartford Courant, November 21, 1774.

[47] Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 152.

[48] Thompson, The United States Army Chaplaincy, 114.

[49] “John Cleveland Papers,” Congregational Library and Archives, www.congregationallibrary.org/nehh/ series2/CleavelandJohnPapers. The name is spelled Cleveland or Cleaveland.

[50] “Journal of Mary Cleveland,” John Cleveland Papers (Salem, MA: Peabody Essex Institute Historical Folders).

[51] Christopher M. Jedrey, The World of John Cleveland: Family and Community in Eighteenth Century New England (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1979), 131-132.

[52] John Cleveland, “To the Inhabitants of New England,” Essex Gazette, April 18 and 25, 1775.

[53] John Cleveland, Essex Gazette, May 31, 1774.

[54] Jedrey, The World of John Cleveland of Ipswich, Massachusetts, 135.

[55] Kenneth Lawson, A Historical Overview of the Militia Chaplaincy in Massachusetts (Milford, MA: Massachusetts Army National Guard, 1997), 7.

[56] Crowder, Chaplains of the Revolutionary War, 43.

[57] Thompson, From its European Antecedents to 1791, 116-117.

[58] Ibid., 138.

[59] For example, Rev. David Avery of Norwich, Connecticut was converted under Whitefield’s preaching in 1764, was educated in Connecticut, and served as a chaplain with Massachusetts and colonial army regiments. Rev. Ebenezer Cleveland was expelled from Yale College for his pro-Whitefield theology, and served as a chaplain with the 21st Infantry Regiment at the Battle of Bunker Hill and in colonial army operations in New York and New Jersey. Rev. Manasseh Cutler of Ipswich, Massachusetts heard Whitefield preach several times and supported the itinerant minister. Cutler served as a colonial army chaplain in 1776 with a Massachusetts regiment, and with another regiment in 1778. Rev. Naphtali Daggett taught at Yale College and welcomed Whitefield and the revival to campus in 1764. When the British invaded New Haven, Connecticut in 1779, Daggett served as a chaplain to the Yale student militia. Rev. Benjamin Pomeroy was seventy-one years old when he served as a chaplain at the Battle of Bunker Hill. A generation earlier, Pomeroy signed the 1743 Testimony of New England clergymen in support of George Whitefield. Pomeroy again served as a colonial army chaplain in 1777. Dozens more New England clergymen could be added to this list of pro-Whitefield clergy who served as military chaplains in the Revolutionary War.

[60] For a thorough study, see Cedric B. Cowing, The Great Awakening and the American Revolution: Colonial Thought in the Eighteenth Century (Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Company, 1971).

[61] Headley, The Chaplains and Clergy of the American Revolution, 16.

[62] Daniel N. Gullotta, “The Great Awakening and the American Revolution,” Journal of the American Revolution, allthingsliberty.com/2016/08/great-awakening-american-revolution/.

[63] Thomas S. Kidd, George Whitefield: America’s Founding Father (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014); Stephen Mansfield, Forgotten Founding Father: The Heroic Legacy of George Whitefield (Nashville, TN: Highland Books, 2001).

[64] Jerome D. Mahaffey, The Accidental Revolutionary: George Whitefield and the Creation of America (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2011).

[65] William J. Bennett and John T.E. Cribb, The American Patriot’s Almanac (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2008), 402.

[66] Mouheb, Yale Under God, 63. An example of an “irreligious” endorser of George Whitefield was Benjamin Franklin of Philadelphia. Franklin never accepted Whitefield’s preaching on the new birth, but he did support Whitefield’s influence upon the fledgling nation. See Randy Peterson, The Printer and the Preacher: Ben Franklin, George Whitefield, and the Friendship that Invented America (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Books, 2015).

[67] Mouheb, Yale Under God, 64.

[68] Gullotta, “The Great Awakening and the American Revolution,” 2-3.

One thought on “Rev. George Whitefield’s Influence on Colonial Chaplains in the American Revolution”

Thank you very much for this well-researched article. I have long studied Whitefield but didn’t know of these chaplains. Well done. I also visited Whitefield’s crypt in the Newburyport Church 30 years ago. You can also read between the lines and understand the concern of the founders that America’s liberty include the separation of church and state (that is that the state has no ground for interfering in ecclesiastical matters of belief or practice).

R. John Campbell

London, ON Canada