In Douglas S. Freeman’s biography of Robert E. Lee, he noted:

Corps activities took a certain amount of Lee’s time that winter. Kosciuszko was in those days the patron saint of West Point. He had designed the Revolutionary forts, Clinton and Putnam, and had resided in the little cottage that had been preserved. For some years, the corps had been contributing twenty-five cents monthly per man toward the construction of a monument in honor of the Lithuanian supporter of American Independence.[1]

As early as 1775 it was apparent to both the Americans and the British of the strategic importance of the Hudson River (also called the North River). On May 25, 1775 the Continental Congress passed a resolution:

Resolved, that a post be also taken in the highlands on each side of the Hudson’s River and batteries erected in such manner as will most effectually prevent any vessels passing that may be sent to harass the inhabitants on the borders of said river; and that experienced person be immediately sent to examine said river in order to discover where it will be most advisable and proper to obstruct the navigation.[2]

The Americans’ initial fortifications in the Highlands were located at the mouth of Popolopen Creek where Forts Montgomery and Clinton were erected and a few miles upstream on an island, Martelaer’s Rock (renamed Constitution Island), while a few cannons were placed atop West Point.[3]

In October 1777, Gen. Sir Henry Clinton led a British force from New York City in an attempt to cooperate with Gen. John Burgoyne’s army on his march south from Canada. As for the effectiveness of the American barriers, landing troops downstream and proceeding overland, Clinton’s force quickly captured all three. However, with Burgoyne’s surrender, Clinton retreated back to New York City after destroying the fortifications. The question arose as to why those forts were so easily captured? Much to the chagrin of American Gen. George Washington, it was that they did not protect the land approaches—the guns, walls, and obstacles focused on the river, while land approaches to the defenses had been overlooked.[4]

While the American victory at Saratoga thwarted the British attempt to control the strategically vital Hudson River, its defense became an even higher priority. To this end, Congress directed Washington “to send one of the four Engineers to do duty at Fort Montgomery and the defences on Hudson’s River.”[5] These four French military engineers, Maj. Louis Duportail, Captains Louis La Radiere and Jean de Loumoy, and Lt. Jean de Gouvan, had arrived in Philadelphia in July 1777 with contracts for appointments with the Continental Army. As part of their agreement of service, they were to be promoted two grades above their regular rank in the French Army. Eventually Duportail was promoted to brigadier general and made chief engineer.[6]

As a result, Washington sent the following order to now-Lt. Col. Louis Radiere: “I desire you will immediately proceed to Fort Montgomery and there take upon you the direction of such Works as shall be deemed necessary by the commanding Officer in that department.”[7] Radiere’s first duty was to find a location where the fortifications could most advantageously be constructed. A group consisting of Radiere, Gen. Israel Putnam (commander of the army in the Hudson Highlands), Gov. George Clinton, his brother Gen. James Clinton and a number of prominent individuals surveyed the Highlands. Eventually two sites were identified: West Point and the Popolopen Creek where the ruins of Fort Clinton lay. The Americans were unanimous in their choice of West Point, while Radiere decided on site of the destroyed Fort Clinton.

West Point offered what was believed an ideal site because it had suitable terrain for erecting a fortification and because the Hudson narrowed and made two abrupt turns that would force ships to lose sail and slow down. It was also directly across the river from Constitution Island.[8] Nonetheless, Radiere was adamant on his choice of Fort Clinton. In a move to placate him, a new commission was appointed to reassess the choices. The new group once again unanimously chose West Point[9]

The Frenchman continued his objections to West Point; he wrote to General Putnam, the New York Provincial Congress and George Washington detailing his choice of Fort Clinton. Once again New York appointed another commission to review the options and again West Point was selected. A frustrated Putnam wrote to Washington voicing his displeasure with Radiere’s obstinacy; after describing how the West Point site was selected, he stated:

I have directed the Engineers to Lay out the Fort Immediately—but he seemes greatly disgusted, that every thing does not go as he thinks proper, even if Contrary to the Judgment of every other person—In short he is an excellent paper Engineer, and I think it would be as well for us if he was employd wholly in that way—I am Confident if Congress could have found Business for him, with them, our Works, would have been as well Constructed & much more forward than they now are.[10]

The main problem with Radiere’s plan was that he envisioned a large and elaborate fortress in the style French engineer Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban, an endeavor that would expend time and resources that the Americans could not afford.[11] It was into this maelstrom that a French-trained Polish military engineer was thrust: Colonel Thaddeus Kosciuszko.

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kosciuszko, a son of a minor Polish noble, received an excellent education in military engineering as a cadet at the new military academy established in Poland by King Stanislaw II Augustus Poniatowski.[12] In 1769, Captain Kosciuszko was given a stipend to go to France, where for the next five years he studied military engineering based on the curriculum of the French military engineering school, Ecole de Genie, at Mezeires.[13] While in France he not only studied military subjects but also art, sculpture, and in what was to have a profound effect on his life, he absorbed the teachings of the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

When Kosciuszko returned home in 1774, there was in reality no Polish Army to employ his military engineering skills.[14] Kosciuszko then became involved in an untenable personal situation and returned to France.[15] In June 1776 he sailed to America to offer his services as a military engineer in the cause of American Independence, having arrived in Philadelphia in August.[16] On October 18, 1776 the Continental Congress Journal noted: “The Board of War brought in a report which was taken into consideration; Whereupon, Resolved, That Thaddeus Kosciuszko, Esq., be appointed an engineer in the service of the United States, with the pay of sixty dollars a month and the rank of Colonel.”[17]

During his time in Philadelphia, Kosciuszko became acquainted with Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates who in February 1777 became the military commander of Philadelphia. This acquaintanceship became a lifelong friendship and when Gates was given command of the Northern Department, he appointed Kosciusko his chief engineer. Kosciuszko’s military engineering skills were put to good use impeding the enemy during the retreat from Ticonderoga, and then in devising defensive positions on Bemis Heights and the surrounding area that helped lead to the American victory at Saratoga. After that Kosciuszko remained in Albany, improving defenses in the area. It was at this time that Washington, writing to Congress about the question of whether to promote the four French engineers, first mentioned Kosciuszko: “While I am on this Subject, I would take the liberty to mention, that I have been well informed, that the Engineer in the Northern Army (Cosieski, I think his name is) is a Gentleman of science & merit. From the character I have had of him, he is deserving of notice too.”[18]

On November 26, 1777, Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates was appointed by Congress to be the president of the newly reconstituted Board of War that had oversight in military procurement and personnel decisions. As things were not progressing in building the fortifications at West Point, Gov. George Clinton complained to Gates about Radiere:

I fear the Engineer who has the direction of the works is deficient in point of practical Knowledge; without which although possessed of ever so much scientific I need not mention to you Sir, how unfit he must be for the present Task, the Chief Direction & Management of which too requires a Man of Business & Authority.[19]

Cognizant of the problems in the Hudson Highlands, on March 5, 1778, the Board of War ordered: “That Col. Kosciuszko be directed to repair to the Army under General Putnam, to be employed as shall be thought proper in his Capacity of an Engineer. Horatio Gates, President”[20]

Kosciuszko, who had been in York, Pennsylvania, where Congress was in session, returned to Albany to retrieve his belongings.[21] He then set out for West Point, first stopping at Poughkeepsie to meet with Governor Clinton. As a result of this meeting, he brought the following letter of introduction to Brig. Gen. Samuel Parsons who commanded at West Point:

Colo. Kusiake who by Resolve of Congress is directed to act as Ingineer at the Works for the Security of the River will deliver you this: I believe you will find him an Ingenous Young Man & is posed to do every Thing he can in the most agreeable Manner.[22]

With the support of General Gates and Governor Clinton, Thaddeus Kosciuszko arrived at West Point on March 26, 1778. One problem with this Board of War decision was that no one consulted or informed General Washington.

In March 1778, the time of Kosciuszko’s appointment, Washington made a change in the command structure in the Hudson Highlands, replacing General Putnam with Gen. Alexander McDougall. On a visit to West Point, it became evident to McDougall that there was a problem with two “chief” engineers on the same project. From the start, La Radiere and Kosciuszko did not get along. Gen. McDougall reported to Washington,

Mr. Kosciousko is esteemed by those who have attended the works at West-point, to have more Practice than Colo. Delaradiere. And his manner of treating the people more acceptable, than that of the latter; which induced Genl Parsons & Governor Clinton to desire the former may be continued at West-point. The first has a Commission as Engineer with the Rank of Colonel in October 1776—Colonel Delaradieres Commission I think is dated in November last, and disputes Rank with the former, which obliges me to keep them apart.[23]

Washington made a decision as to who would be in charge of building the fortifications at West Point when he told McDougall: “As Colo. La Radiere and Colo. Kosiusko will never agree, I think it will be best to order La Radiere to return, especially as you say Kosiusko is better adapted to the genius and temper of the People.”[24] With Radiere relieved of his post, Thaddeus Kosciuszko was able to begin construction of what he envisioned for West Point’s fortification.

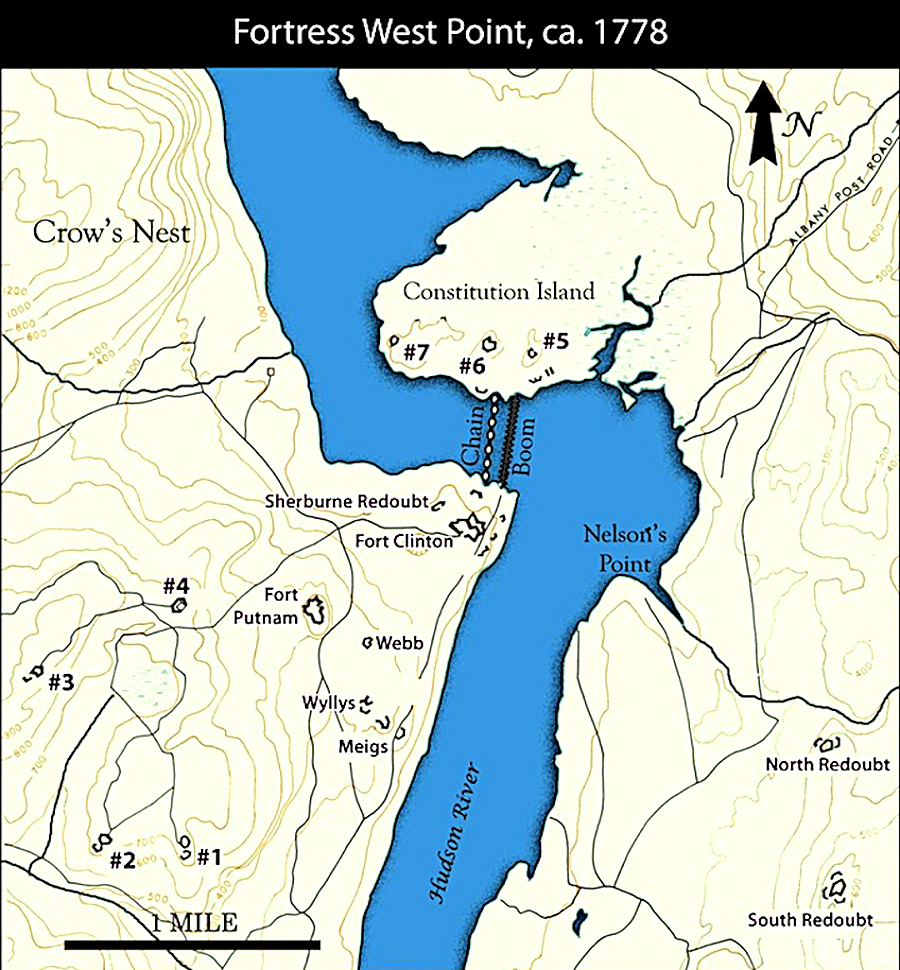

Kosciuszko’s plan was to have an integrated system of forts sited on commanding terrain. The key was a bastion located 145 feet above the Hudson on what is known as “The Plain.” Originally it was constructed of tree trunks piled on top of a rock ledge, supported by hand-hewn stones.[25] Sited along the river were four batteries of artillery to protect the “Great Chain,” built by Capt. John Machin at the Sterling Irons Works. The chain and boom, first emplaced in April 1778, were stretched across the river to Constitution Island.[26] At the same time protecting batteries were emplaced on the rebuilt fort on Constitution Island. By July 1778 the fortification, named Fort Clinton, was basically completed. While Fort Clinton was formidable, the key to Kosciuszko’s design was to construct a layered, integrated network of fortifications for mutual defense. For this he turned to the hills surrounding The Plain.

Above Fort Clinton were two steep hills, Crown and Rocky; initially they had been deemed unscalable, with no need to fortify them. Kosciuszko surveyed the area and disagreed with this assessment. He convinced General McDougall to change his mind, and work began on Crown Hill that eventually became known as Fort Putnam (named for Col. Rufus Putnam). It was the most important protection for Fort Clinton/Arnold.[27] Kosciuszko also wanted to fortify Rocky Hill that overlooked Fort Putnam, but for the present, his superiors felt it was too steep for an enemy to occupy. Colonel Kosciuszko then turned to the construction of supporting redoubts near The Plain that became known as Forts Webb, Wyllys, and Meigs, named for the commanders of the Connecticut troops who constructed them. As to their placement it was noted:

None of the individual positions was especially strong, but collectively the whole scheme was formidable. The various works were mutually re-enforcing forming a system of interlocking defenses quite novel at the time. Each was carefully sited to draw maximum advantage from the terrain.[28]

The conclusion to Fortress West Point was the addition of four more redoubts supporting Fort Arnold/Clinton, numbered 1, 2, and 3. Following a visit by George Washington, who on an inspection tour of the fortifications agreed with Kosciuszko’s assessment about Rocky Hill, the height above Fort Putnam was fortified with Redoubt 4. Then on Constitution Island, Redoubts 5, 6, and 7 were built to provide further protection for the Great Chain. By the end of 1779, Fortress West Point was basically completed. Within its defenses were approximately sixty cannons sited to stop any enemy naval force sailing up the Hudson River or an attempt by land forces as the British had done down river in October 1777 when they captured Forts Montgomery and Clinton.

Even with all of Kosciuszko’s success, first at Saratoga and then at West Point, he continued to be a target of jealousy and distain by the French engineers, particularly General Duportail and Lieutenant Colonel Radiere. Added to this was sniping from some Continental Army officers mainly due to his relationship with General Gates; as one biographer put it: “Kosciuszko was one of the officers who basked in Gates’ sunshine.”[29] Nonetheless, from their first meeting on July 16, 1778 at West Point, Colonel Kosciuszko had the full support of General Washington.

With the basic fortifications completed, the urbane Polish noble found life at West Point quite tedious. When he first arrived he took a room in a boarding house, but later he had a log cabin constructed where he lived. In the same area Kosciuszko began a garden that became a delight to him and visitors.[30] One of the things that he missed was the camaraderie with the friends he made on the Saratoga campaign. On September 14, 1778, Kosciuszko wrote the following letter (in his broken and phonetic English) to John Taylor, a friend he knew in Albany, lamenting his assignment:

Dear Sir: I am the enhappy man in the World, because all my Jankees the best Frinds is gone to Whit Plains or Eastern and left me with the Skoches and Irishes impolites as the Savages. The satisfaction thad I have at the present only is this to go all day upon the Works and the Niht to go bed with the Cross Idea of lost of good Compani.

I should go to the Eastern with General Gates but gl. Washington was obstacle of going me ther and I am verry sorry of it.

My respect to Mistris Skayler and miss Kayler do not forgive, to your lady and to all my Frinds give my Compliments.

Your most remember thad if I go to Albany I most be in your house.

Your Frind

Thad. Kosciuszko, Colo[31]

Life at West Point did become a little more bearable for Kosciuszko when Brig. Gen. John Patterson was appointed as the garrison commander in December 1778, another friend he made during the Saratoga Campaign when they were both at Fort Ticonderoga. With Patterson, serving as his orderly, was a free Black, Agrippa Hull, who had joined the Continental Army when he was eighteen years old in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. When Patterson left West Point he offered Hull’s service as an orderly to Kosciuszko who was glad to accept. “Grippy” as Agrippa Hull was known, remained with Col. Kosciuszko for the next five years until he left for Poland in 1784.[32]

The only threat to West Point came in May 1779 when Sir Henry Clinton led an incursion up the Hudson River that took Stony Point, approximately fifteen miles to its south.[33] In reality this movement was a diversion to try to entice Washington into a full-fledged battle, which he did not accept. By 1780, all that remained to do at West Point were the monotonous tasks of repairing and upgrading existing structures and emplacements. It was at this time that the British implemented their southern strategy.

When General Gates was ordered by Congress to replace Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, who surrendered his army at Charleston, South Carolina in May 1780, he wrote to Washington asking that Kosciuszko be assigned to his command.[34] Washington replied that Kosciuszko was still needed at West Point and couldn’t be released. In July 1780 Kosciuszko himself wrote to Washington asking to be assigned to Gates’ staff.[35] At this point Washington relented, indicating that the main reason for this was that General Duportail had been taken prisoner at Charleston.[36]

So, after serving a total of twenty-eight months constructing and improving the fortifications at West Point, Col. Thaddeus Kosciuszko got his wish to return to an active, front-line command. He left West Point along with his orderly Agrippa Hull on August 7, 1780, two days after Benedict Arnold took command of the Hudson Highlands.[37] Before he reached the Continental Army’s headquarters in South Carolina, Gates had been routed at Camden and was replaced by Gen. Nathanael Greene, on whose staff Kosciuszko remained for the remainder of the war.

How then can we look at the work of Col. Thaddeus Kosciuszko, the “Patron Saint of West Point”? As Col. David Palmer wrote: “The post’s obvious strength deterred attack, the British never dared to try for it. . . . For there American revolutionaries and a Polish engineer had built a fortress quite ahead of its time—a 19th Century fortified complex in an 18th Century war.”[38] Historian Frank Galgano noted:

Kosciuszko’s fortification concept was at the same time revolutionary, complex and elegant. The West Point fortification system unlike earlier attempts on Constitution Island and Popolopen Creek—was truly integrated, mutually supporting, and took fullest advantage of the dominating terrain and configuration of the river.[39]

A final evaluation of Kosciuszko’s work comes from Donald Sambaluk, who wrote of an overlooked aspect of Kosciuszko’s engineering skills: “Impressively, Kosciuszko’s defensive concept not only turned the complex terrain into an advantage but also made timely use of the materials and labor that was available.”[40]

The collection of funds by the cadets at West Point and the eventual erection of the Kosciuszko Monument was a well-deserved honor for a foreign volunteer who not only provided valuable military service to the American cause but also believed in the precepts of freedom and republicanism it represented and that he cherished for the remainder of his life.

[1]Douglas S. Freeman, R. E. Lee: A Biography (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), 70. For a detailed discussion of the use of the term “patron saint of West Point,” see: Anthony J. Bajdek, “The Patron Saint of West Point: Tadeusz Kościuszko and His Academy Disciples,” Polish American Studies 76, no. 2 (2019): 47-63. According to Alex Storozynski, it has been suggested that Kosciuszko “prodded” Thomas Jefferson to open a military academy at West Point. Alex Storozynski, The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution (New York: St. Martin Press, 2009), 88.

[2]Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774-1789, Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed. (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1904-37), 2:60 (JCC).

[3]This Fort Clinton was named for Gov. George Clinton while the Fort Clinton at West Point was named for his brother Gen. James Clinton.

[4]Col. David R. Palmer, “Fortress West Point: 19th Century Concept in an 18th Century War,” The Military Engineervol. 68, no. 443 (1976): 172.

[6]Richard K. Wright, Jr., The Continental Army(Washington: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1982), 123. For a detailed history of the service of the Engineer Corps, see: Paul K. Walker, Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution (Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific, 2002, reprint). It wasn’t until May 1779 that Congress created a separate Corps of Engineers.

[7]George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel La Radière, October 8, 1777,” Founders Online,National Archives. La Radiere is most often referred to as Radiere.

[8]Col. Francis C. Kanjecki, Thaddeus Kosciuszko: Military Engineer of the American Revolution (El Paso: Southwest Polonia Press, 1998), 65.

[9]Congress originally put the responsibility for the defense of the Hudson Highlands with the state of New York, which explains the input of Gov. George Clinton.

[10]Israel Putnam to Washington, January 13, 1778,”Founders Online, National Archives.

[11]Sebastien le Prestre Vauban (1633-1703) French military engineer who revolutionized the art of siege craft and defensive fortifications.

[12]At the time of his birth this region was known as Polesie in the eastern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth; today it is in Belarus. Kosciuszko preferred to use his second name Tadeusz, when he came to America he anglicized it to Thaddeus.

[13]Foreigners were not allowed to enroll at the Ecole de Genie.

[14]In 1772, Poland experienced the first of three Partitions by Russia, Prussia and Austria with the result that the Kingdom of Poland was limited to a 100,000-man army.

[15]For the reason he was forced to leave Poland see: Francis C. Kanjecki, Thaddeus Kosciuszko: Military Engineer of the American Revolution, and Joseph Wroblewski, “John Paul Jones and Thaddeus Kosciuszko: Encounter in Warsaw 1789,” Journal of the American Revolution, October 14, 2020.

[16]Unlike most foreigners seeking commissions in the Continental Army who had received letters of recommendation from the American commissioners in France, Kosciuszko went to America with no recommendations. For a brief review of Kosciuszko’s qualifications as a military engineer, see: Gene Procknow, “Top 5 Foreign Continental Army Officers (Other Than La Fayette),” Journal of the American Revolution, November 4, 2014.

[18]Washington to Henry Laurens, November 10, 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives. In various writings Washington spelled Kosciuszko’s name eleven different ways!

[19]Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York, 1777-1795, 1801-1804 (New York: Wynkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co. State Publishers, 1899-1914), 2:712.

[21]While at York, Kosciuszko served as General Gates’ “Second” in a duel with Gen. James Wilkinson; he was Gates’ second at another duel with Wilkinson at White Plains the following year.

[22]Public Papers of George Clinton, 3:85-86.

[23]Alexander McDougall to Washington, April 13, 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives. Brig. Gen. Samuel Parsons of Massachusetts was put in command of West Point.

[24]Washington to McDougall, April 22, 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives. La Radiere died in 1779.

[25]The arrival of Connecticut troops in January 1778 at West Point makes it today the site of longest continuously occupied U.S. Army garrison in the United States.

[26]For an excellent history of the Great Chain, see: Hugh T. Harrington, “The Great West Point Chain,” Journal of the American Revolution, September 25, 2014.

[27]Originally named Fort Clinton after Gen. James Clinton whose troops did the majority of the work on it; then renamed Fort Arnold following a visit of Benedict Arnold that spring. Following Arnold’s treachery it was renamed once again Fort Clinton.

[28]Palmer, “Fortress West Point,” 173. A redoubt was a fort or fort system usually consisting of an enclosed defensive emplacement outside a larger fort, constructed of earthworks, stone or brick.

[29]Storozynski, The Peasant Prince, 60.

[30]Today the site of his cabin is where the Kosciuszko Monument is located and his garden is still maintained; for a description see: Kosciuszko Garden, http://www.usma.edu/Tour/KosciuszkoGarden.asp.

[31]Autographed Letters of Thaddeus Kosciuszko, Metchie J. Budka, ed. (Chicago: Polish Museum of America, 1977), 28. John Taylor was a banker and merchant plus a colonel in the Albany militia; “miss Kayler” was Betsy Schuyler, the daughter of Gen. Philip Schuyler who married Alexander Hamilton.

[32]For the nickname “Grippy,” see Kanjecki, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, 101 and Storozynski, The Peasant Prince, 72. A few of accounts incorrectly identify Hull as a “slave” who was “given” to Kosciuszko by Patterson and eventually Kosciuszko freed him. This error is traced back to a great grandson, Thomas Egleston, who wrote a biography of Patterson. For an extensive presentation on the story of Hull and Kosciuszko’s relationship see: Gary B. Nash and Graham Hodges, Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Tadeusz Kosciuszko and Agrippa Hull (New York: Basic Books, 2008), 55-70.

[33]Adam E. Zielinski, “Battle of Stony Point,” American Battlefield Trust, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/stony-point-battle

[34]Horatio Gates to Washington, June 21, 1780,”Founders Online, National Archives.

[35]Thaddeus Kosciuszko to Washington, July 30, 1780,”Founders Online, National Archives,

[36]Washington to Kosciuszko, August 3, 1780,”Founders Online, National Archives. In footnote four it details Kosciuszko’s request to bring Agrippa Hull with him as his orderly, and Washington’s permission to do so.

[37]The only effect of Benedict Arnold’s action involving Kosciuszko was that he left a trunk full of papers and maps at Mrs. Warren’s boarding house; when word came of a possible British attack, she destroyed them. For details about this incident see: Kanjecki, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, 122.

[38]Palmer, “Fortress West Point,” 174.

[39]Frank Galgano, “Decisive Terrain,” Studies in Military Geography and Geology (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2004), 119.

[40]Nicholas M. Sambaluk, “Making the Point—West Point’s Defenses and Digital Age Implications, 1778-1781,” Cyber Defense Review (Summer 2017), 151.

Recent Articles

The Monmouth County Gaol and the Jailbreak of February 1781

The New Dominion: The Land Lotteries

The Home Front: Revolutionary Households, Military Occupation, and the Making of American Independence

Recent Comments

"Hero to Zero? Remembering..."

I did come across this record, it adds a little bit: He...

"Hero to Zero? Remembering..."

How did Gates's son Robert die? I have not been able to...

"A Strategist in Waiting:..."

Lots of general information well presented, The map used in this article...