In 1775, the Continental Army was in dire need of engineers. The colonies did not have a War College or military academy like the Ecole Militaire in Paris or the Royal Military Academy in London. Gen. George Washington complained to Congress, “The Skill of those engineers we have … [is] very imperfect and confined to the mere manual exercise of cannon, whereas the war in which we are engaged, requires a Knowledge comprehending the Duties of the Field and Fortifications.” 1 Americans had little experience in laying siege, erecting field fortifications, laying out camps, or mapping terrain.

In April of 1776, Congress sent Silas Deane to France. One of his duties was to recruit engineers for the Continental Army. He (and later Benjamin Franklin) would enlist Philippe Charles Tronson du Coudray, Louis Lebegue Duportail, Jean Baptiste Joseph de Laumoy, and Louis de Shaix La Radiere. Little did Deane or Franklin realize that the greatest engineer to come from France was not French at all, but rather Polish. He was Thaddeus Kosciuszko. Washington had originally mistaken him for a French engineer because, not knowing English and not sure if anyone in the colonies spoke Polish, Kosciuszko chose when he arrived to speak French. On December 9, Washington gave the “French Engineer of eminence in Philadelphia” his first task: “to view the Grounds and begin to trace out the Lines and Works” – in other words, fortify the city. 2

Kosciuszko’s work impressed his superiors so much that in the spring of 1777 he accompanied Gen. Horatio Gates north to Fort Ticonderoga. His task was to evaluate the fort’s defenses and recommend changes where necessary. In a very short period of time he would strengthen the fortifications on Mount Independence and complete the log bridge connecting the same to Fort Ticonderoga, however, his most important change was never agreed to. Not far from the fort was Sugar Loaf Hill. Kosciuszko wanted cannon placed atop the hill: “a battery so placed, from elevation and proximity, would completely cover the two forts, the bridge of communications and the adjoining boat harbor.” 3 Unfortunately, the commanding officer of the northern army, Gen. Philip Schuyler,

reasoned that no Engineer hitherto, French, British, or American , had believed in the practicality of placing a battery on Sugar Loaf hill, [and he] was not disposed to embarrass himself or his means of defense by making the experiment. 4

On July 1, British Gen. John Burgoyne and his army of nearly 8000 marched on the fort. His engineer, William Twiss, and chief of artillery, Gen. William Phillips, immediately recognized the tactical advantage the British army would have with cannons atop the hill. By July 5, six British cannons were looking down on the fort. Faced with point blank bombardment as well as the possible destruction of the bridge, Gen. Arthur St. Clair had little choice but to evacuate the fort that same day under the cover of darkness.

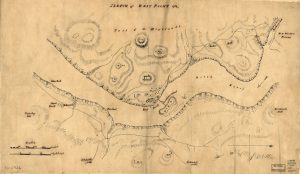

Kosciuszko would be faced with a similar situation in the spring of 1778, however this time, he would have the authority to make all of the changes that were necessary. The British believed that the war would be short lived if the New England colonies could be isolated from the other colonies. To do this, the British needed to take control of the Hudson River; Washington wanted to prevent this. On January 13, 1778, Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam informed Washington that “the place … to obstruct the navigation of Hudson River was at West Point.” 5 On January 20, Brig. Gen. Samuel Parsons and his 1st Continental Brigade arrived and broke ground. The engineer appointed to design and oversee the construction was Col. Louis de Shaix La Radiere. On February 12, Putnam returned to Connecticut to take care of private matters; this led to the temporary appointment of Parsons as commander of West Point. La Radiere’s inability to get along with Parsons and some of the other officers forced Congress to replace him with Kosciuszko on March 5. 6 Eleven days later, Washington appointed Gen. Alexander McDougall as the new commanding officer of West Point. Kosciuszko arrived on March 26; McDougall on March 28. It did not take long for McDougall to recognize the abilities of Kosciuszko, especially when he recommended that a fortification be built on Crown Hill above Fort Clinton. McDougall with the advice of his officers agreed to Kosciuszko’s plan. On April 22, Washington recalled La Radiere to Valley Forge: “I think it will be best to order La Radiere to return, especially as you say Kosciusko is better adapted to the genius and temper of the people.” 7

At the beginning of March, another officer had been appointed to West Point; his name was Col. Rufus Putnam. He was a self-taught surveyor and a student of mathematics. In 1776 he had been appointed an engineer for the colony of New York and the following year served with Kosciuszko at Saratoga. On March 28, he and his men arrived at West Point. What lay before them was

A Battery … to anoy the Shiping in case [the British] Should come up & attempt to turn the point & force the Boom … and a number of Small works or chain of Forts & Redoubts, were Laid out on the high grounds bordering the plain, which forms the point. 8

During his two-month stay, his task would be to build a fort “on a high hill, or rather rock, which command[ed] the plain and point.” McDougall and Kosciuszko were convinced that “the hill which Colonel Putnam [was] fortifying [would be] the most commanding and important of any” at West Point. 9 Before the summer was out, the forts that would be manned by the regiments of Col. Samuel Webb, Col. Return Jonathan Meigs, and Col. Samuel Wyllys were also under construction, as were Redoubts North and South on the east side of the Hudson.

Kosciuszko was making significant progress when the chief engineer for the Continental Army, Brig. Gen. Louis Duportail, arrived at West Point on September 9, 1778. His orders of August 27 read,

proceed as speedily as convenient to the Highlands and examine the several fortifications carrying on there for the defense of the North River. When you have done this you will make a full report of their state and progress. 10

In his report to Washington four days later, he cited three concerns. There was only one battery on Constitution Island: “to secure the Chain on the left-hand Shore of the River … there is no enclosed work … to hinder the enemy from debarking a sufficient number of men to get possession of the ground and cut the Chain. There is only a battery.” The bomb- proof in Fort Putnam was inadequate: “to have bomb-proofs sufficient for three fourths of the Garrison, magazines, etc … I am told Col. Koscuiszko proposes … one but which will not suit more than 70 or 80 men. This is far from sufficient.” And Rocky Hill needed to be fortified: “There is indeed a height, which commands [Fort Putnam] … it would be very difficult for an enemy, even when master of it to bring heavy cannon there. Besides it would be too far to make a breach. This fort has nothing to fear.” 11 On September 19, Washington visited West Point to follow up on Duportail’s report. After completing his tour, Washington praised Kosciuszko’s “complex redoubt and fort system.” But what was the system he was referring to?

The system involved a multi-elevated defense, employing batteries, redoubts and forts, around a single object, the Great Chain. Each position was selected and constructed based upon purpose, materials available and terrain. The first level was designed by Major General Putnam and Colonel La Radiere; it included the Lanthorn, Chain, South, and Water batteries and Fort Clinton, that protected the Chain. The second and third levels were designed by Kosciuszko. The second included Forts Webb, Wyllys, and Meigs that protected the southern approaches, Fort Putnam that protected Fort Clinton, and Redoubts 5, 6, and 7 on Constitution Island that protected the island’s batteries (Marine, Hill Cliff, and Gravel Hill). The third included Redoubts 1, 2, 3 that extended the southwestern defenses, Redoubt 4 that protected Fort Putnam, and the North and South Redoubts, located on the east side of the Hudson, that protected the landward approaches to Constitution Island. All of the redoubts were early warning posts that could also force an enemy to deploy their forces. Forts Clinton and Putnam were designed to withstand a siege for ten days; this was considered enough time for the Continental Army to come to their aid. The four redoubts in the outer circle were designed and constructed to withstand an infantry assault.

Kosciuszko was adamant that Fort Putnam needed protection from above. He believed Redoubt Number 4, atop Rocky Hill almost one-half mile west of Fort Putnam, could offer just that. It would serve as the overwatch position for Fort Putnam that in turn served as the overwatch position for Fort Clinton. Fort Clinton was 167 feet above the Hudson; Fort Putnam was 322 above Fort Clinton; and Redoubt Number 4 was 321 feet above Fort Putnam. 12 Kosciuszko was fully aware that if the British took control of Rocky Hill, they would be able to bombard Fort Putnam just as they were able to bombard Fort Ticonderoga from Sugar Loaf Hill.

On April 25, 1779, General McDougall provided Kosciuszko with specific instructions for building Redoubt Number 4. He was to make the blockhouse bombproof, enclose the blockhouse in a redoubt, build the parapet strong enough to withstand artillery, build a cellar to hold 30 days of supplies if possible, and build the redoubt large enough to quarter 100 men. Kosciuszko’s original plan called for the redoubt to be hexagonal in shape, however, when fully constructed, it was heptagonal. 13 This author has found no clear explanation for the change. Possibly there was a shortage of labor, materials or money, or the British activity around Stony Point forced quick construction. The redoubt had a reentrant angle of 120o that faced west, the direction of any anticipated attack. 14 It was designed to allow crossfire. The southeastern and northeastern sides faced the defensive positions of West Point further down the hill. The entrance to the redoubt faced directly east. The ramparts were made of soil over five feet of stone. The powder magazine was located on the north side of the redoubt. South and east of the redoubt were sheer cliffs and rocky ledges; an assault from either direction was next to impossible. North and west of the redoubt was a twelve-foot wide ditch that provided an additional defense against the only directions from which a possible attack could occur. The interior circumference was the largest of the four outer redoubts at 235 feet and it did not have a detached battery like the other three. 15

On July 16, Gen. Anthony Wayne led a successful attack on Stony Point, the British fortification twelve miles south of West Point on the Hudson. Washington, concerned that the British might attempt the same against West Point, wrote to St. Clair who had recently arrived at West Point,

You will be pleased to examine the long Hill in front of Fort Putnam, at the extremities of which the Engineer [Kosciuszko] is commencing some works … The possession of this Hill appears to me essential to the preservation of the whole post and our main effort ought to be directed to keeping the enemy off of it. 16

Washington was referring to Rocky Hill and Redoubt Number 4. He knew the value of controlling the high ground, not only because of the error in judgment regarding Sugar Loaf Hill near For Ticonderoga, but because he had suffered a similar fate against the French on July 3, 1754 as the commanding officer of Fort Necessity. Washington knew if Redoubt Number 4 fell, Fort Putnam would eventually fall and the domino effect would continue all the way down to the Hudson.

On June 16, 1780, Maj. Gen. Benedict Arnold, who would be named its commanding officer two weeks later, visited West Point and specifically Redoubt Number 4. Afterwards he wrote, “the west side [was] faced with a stone wall 8 feet high and four [feet] thick. No Bomb Proof, two six pounders, a slight abattis [and] a commanding piece of ground 500 yards west” and “I am told the English may land three miles below and have a good road to bring up heavy cannon.” 17

His assessment of the redoubt was not for Washington or Schuyler, but rather for Maj. John André, adjutant general of the British army in New York. Arnold, for reasons of resentment and money, was planning to surrender West Point and control of the Hudson to the British. Fortunately, he did not have some papers that would have made the transfer much easier and less bloody – he did not have Kosciuszko’s detailed plans of each position. Kosciuszko had been summoned urgently to serve in the southern army, and in the rush to depart he forgot to tell his successor, Maj. Chevalier de Villefranche, that he had left the plans with Mrs. Sarah Warren, owner of the boardinghouse where he lived. Because Arnold never found them, he directed Villefranche to create drawings of the works on both sides of the Hudson and to determine the overall strength of the garrison, the size of the force necessary to man each work, and the ordnance at each work. 18 Most of this information was in the possession of André when he was arrested as a spy. Had he returned safely to New York City and had the British attempted to move against West Point, Arnold was ready. On September 5, he had issued a ‘Disposition of the Garrison in case of an Alarm’. The Artillery Orders stated,

Capt. Dannills with his Comp:y [to man] Fort Putnam, and to Detach an officer with 12 men to Wyllys’ Redoubt, a non Commissioned Officer, with 3 men to Webbs Redoubt, and the like number to Redoubt No. 4. 19

According to Villefranche’s report on the size of the force necessary to man each work, Fort Putnam required 450 men, Forts Wyllys and Webb 140 men each and Redoubt Number 4 100 men. If a company was made up of 120 men, then Fort Putnam would have been under-manned by 348 men, Forts Wyllys by 128 men, Fort Webb by 137 men and Redoubt number 4 by 97. The British would have encountered a fortress that had been destabilized and the back door, Redoubt Number 4, left open and defenseless.

We will never know if Kosciuszko’s defense plan would have worked because the

British never attempted an assault on West Point; we will never know if Redoubt Number 4 could have withstood an assault; we will never know if the Redoubt Number 4 fell could the Continental Army get to West Point in time to save Fort Putnam; we will never know … However, we do know that considerable effort was put into the construction of Redoubt Number 4; we do know that Kosciuszko understood better than most how to use the terrain to his advantage, and we do know that Washington fully understood the domino effect if the lynchpin of West Point was removed.

1 Washington to the President of Congress, 10 July 1775, in The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 16 June 1775 – 15 September 1775, ed., Philander D. Chase (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1985), 1: 85-97.

2 Ibid., “George Washington to John Hancock, 9 December 1776,” 7:283-85.

3 Mieczyslaw Haiman, Kosciuszko in the American Revolution (New York: Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences in America, 1943), 16-17.

4 Ibid., 18.

5 “Putnam to Washington, 13 January 1778,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 26 December 1777 – 28 February 1778, ed., Edward G. Lengel (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), 13:228-30.

6 State Historian and Chief, Division of History, Public Papers of George Clinton, First Governor of New York (New York and Albany: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, and Crawford Company, 1900), 2:711-12.

7 ”Washington to McDougall, 22 April 1778,” in The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1 March 1778 – 30 April 1778, ed. David R. Hoth (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004), 14:587–588.

8 Rowena Buell, ed., The Memoirs of Rufus Putnam and Certain Official Papers and Correspondence (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1903), 75.

9 “McDougall, to Parsons, 11 April 1778,” in New York State Library, McDougall Manuscript File, Document No. 7525.

10 “Washington to Duportail, 27 August 1778,” in The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, 1 July – 14 September, 1778, ed., David R, Hoth (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 386.

11 “Duportail to Washington, 13 September 1778,” in The Papers of George Washington,

Revolutionary War Series, 1 July –14 September 1778, ed., David R. Hoth (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006), 16: 594–59.

12 Per Google Maps and Microsoft Virtual Earth.

13 Charles E. Miller, et al., Highland Fortress, The Fortification of West Point During the American Revolution, 1775 – 1783 (West Point, NY: Dept. of History, United States Military Academy, 1979), 140 and 97.

14 Lewis Lochée, Elements of Field Fortification (London: T. Cadell, 1783), 6-7.

15 Douglas R. Cubbison, Historic Structures Report: The Redoubts of West Point (West Point, NY: U.S. Military Academy, 2004), 30-31.

16 “Washington to St. Clair,” The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, 1779 -1781, ed., Harold C.

Syrett (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 107.

17 Edward C. Boynton, History of West Point (London: Sampson Low, Son & Marston, 1864), 114-15; Benedict Arnold to Major André, June 16, 1780,” in The Henry Clinton Papers, William L Clements Library, The University of Michigan.

18 Exhibits referred to in “The Trial of Joshua H. Smith, For Complicity in the Conspiracy of Benedict Arnold and Major André,” in The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America, X, No. 7, (July 1866), Supplement No. V: 135-36.

19 Ibid.

3 Comments

Interesting article, Bob. I know little about the West Point complex and this piece gave me a good introduction not to mention some motivation to do some further reading.

Unlike West Point, I do know a lot about the Mount Independence and Ticonderoga complex and would like to offer a couple comments (I am in the process of preparing a submission to the “Journal” concentrating on Mount Independence). As you say, Kosciuszko had orders to look things over and make recommendations regarding modifications and additions. A few days after his arrival there, the chief engineer on the site, Jeduthan Baldwin, received a letter from Gates recommending that the former take charge of Ticonderoga and the latter concentrate on the works on the Mount [“Gates Papers,” reel 4, May 28, 1777]. Unfortunately, although work continued on the bridge and strengthening the works on the Mount, both efforts moved rather slowly and neither Kosciuszko nor Baldwin oversaw much progress in either project before Burgoyne’s army arrived.

Your comments about Sugar Loaf Hill/Mount Defiance are a common interpretation but they are, regrettably, incorrect. The blame for not putting works up there cannot be placed on Schuyler’s or St. Clair’s respective shoulders. Gates had wanted to build those works in 1776 but never got around to it. In 1777, the army found it impossible to do. The 1776 garrison of around 12,000 men might have been capable of building and occupying it but none of the 3,000 present in 1777 could have been spared to man an isolated outpost. Any guns and troops on Sugar Hill would have been cut off and lost. Kosciuszko surely recognized this fact.

It also needs to be noted that, although shot from Sugar Hill could reach most American positions (a statement doubted by some today), the greatest threat came from the fact that the British could simply sit up there and observe every bit of movement by the Americans. Even worse for the Americans, the British could count the number of troops and quickly deduce that the Americans had vastly inadequate numbers for a proper defense. It is this point, not the threat of bombardment, that is brought up in period sources including St. Clair’s court-martial.

Going back to West Point, I think you may have misinterpreted a source’s statements. When specifying the numbers necessary for the various posts, it appears Arnold’s orders deal with just the artillerymen. I suspect Villefranche’s report is concerned with the numbers of infantry.

On another topic, a full-strength infantry company in the eighteenth century usually had from forty to sixty men but that varied considerably depending on several factors. In service, numbers varied even more dramatically.

One last question: Arnold wrote that he had been told of a landing three miles downriver and a road capable of handling heavy artillery. Any idea of where that landing might be and the road? The only road shown on both maps in your article is enfiladed by American fortifications. Do you think that is the one Arnold refers to?

I would add to Mike’s comments regarding Kosciuszko’s recommendations to Gates regarding the Fort Ti/Mount Independence defenses that there is no clear indication that he proposed fortifying Sugar Hill (or any other specific part of the works, for that matter). His letter to Gates–cited by Haiman above–referred to locations on a map accompanying the letter that has not been found. It is likely that the map was an earlier version of the one he supplied for use at St. Clair’s court martial in 1778; if so, the additional proposed defensive works–indicated as “lines drawn upon the ground”–did not include Sugar Hill, but related to extending the old French Lines on the Ti side and the “Horseshoe Battery” on Mount Independence.

I am attempting to locate the source document for the quoted comment from Schuyler about not “attempting the experiment” of fortifying Sugar Hill. I have doubts about its authenticity, based upon my review of much of Schuyler’s correspondence, as well as his testimony at St. Clair’s court martial. Schuyler’s well documented plans for 1777 never envisioned seriously defending the Ticonderoga side of the lake at all, let alone Sugar Hill, so the quote makes little sense without a lot more context, if it is authentic.

At Redoubt #4, a bicentennial marker indicates that an additional redoubt was planned to be placed on slightly higher ground west of Redoubt #4 but not constructed. However, your article’s thesis is clearly substantiated by visual inspection which indicates that it would be a simple manner for cannon on Redoubt #4 to command Ft. Putnam which commands Ft. Clinton which commands the chain.

Last year West Point reconstructed the western walls of Redoubt #4 and provided easier access to its commanding views.