Jemima Howe (1724–1805), a pioneer woman of the early Vermont frontier wilderness, survived a 1755 abduction along with her seven children ranging from six months to eleven years old, three years of captivity in French-Canada, and three husbands, the first two killed by Abenaki.[1] The early American literary genre of Indian captivity narratives presented the story of Jemima Howe, but cloaked it in myth. As literacy rates rose right after the American Revolution, especially among women, so climbed the popularity of these historical and often religious stories.[2] The burgeoning colonial readership provided the audience for Jemima Howe to become a celebrity, widely known as the “fair captive,” alongside a hero of the American Revolution—her rescuer and suggested romantic lead, Maj. Gen. Israel Putnam—in two competing captivity narratives.

The importance of the captivity narrative in American literary history and its role in creating an American literature cannot be underestimated.[3] One of the first best sellers in this literary genre was The Sovereignty and Goodness of God Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, likely arranged and written at least in part by Increase Mather, Puritan clergyman and president of Harvard, with his son, Cotton Mather, a minister and prolific author following in his father’s footsteps with a well-known captivity narrative about Hannah Dustan. Mrs. Rowlandson’s narrative went through numerous printings from its initial publication in 1682 well into the 1800s and is considered a colonial classic even today.

During the next wave of this literary genre, authors, publishers, and printers kept a particularly close eye on sales and the changing literary tastes of the fast-growing market, especially for sentimental fiction prevalent in captivity narratives such as those about Jemima Howe.[4] The two captivity narratives about her, published during the late 1780s and early 1790s, provide historical context and attest to the significance of these stories in the creation of American literature and myth just after the American Revolution. These founding-era narratives were increasingly secular and partisan, written to reinforce the rejection of British culture and the emergence of one that was uniquely American. They often offered a vision of the universal archetype—the creation of a “potent cultural myth,” a hero who represented an American definition of self.[5] The intertwined captivity narratives of Jemima Howe and Israel Putnam that took place during the French and Indian War fit squarely into the later phase of this literary genre.

The first publication to reference the Howe-Putnam captivity narrative was David Humphreys’ popular 1778 The Essay on the Life of the Honourable Major-General Israel Putnam. A Yale graduate, Humphreys was a confidant and scribe to George Washington, a lieutenant colonel in the American Revolution, foreign statesman, member of the writing group called the Connecticut Wits, and aide de camp to Putnam.[6] In his combined biography, history, and romance, Humphreys devoted five pages of The Essay to the Putnam-Howe narrative which followed the often-cited story about Putnam nearly being burned alive at the stake by French-allied Caughnawaga, his rescue, and his time as a prisoner of war in Quebec where he met the engaging, yet delicate, Jemima Howe. Even if it was not romance at first sight, Putnam’s behavior toward her represented the height of chivalry.

Humphreys portrayed Putnam as Jemima’s protector from her French owners’ lecherous advances and her personal escort on their eventual journey back home to freedom. Humphreys’ TheEssay represented a move away from Biblical or classic archetypes and toward the American-made, born and raised hero. In this popular work, Putnam symbolized cool-headed fearlessness against the jaws of death during wilderness warfare, an unquestioning love of country, and an unwavering sense of duty. On the other hand, Jemima Howe was Putnam’s counterpoint, a sentimental heroine, a victim in distress.[7]

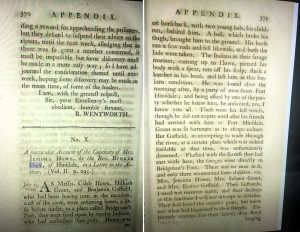

The second publication about Mrs. Howe was a supposed Genuine and Correct Account of the Captivity Sufferings and Deliverance of Mrs. Jemima Howe by long-time local Vermont clergyman, Rev. Bunker Gay, first published in volume three of The History of New-Hampshire by clergyman and historian Jeremy Belknap in 1792. Later that year and with Belknap’s permission, Reverend Gay’s account was extracted from this historical opus for further distribution as a pamphlet.[8] Although the title might suggest otherwise, its so-called veracity was a “standard publishing ploy to boost sales.”[9]

Reverend Gay’s portrayal of Jemima Howe, unlike that of Humphreys, had a psychological orientation that focused on her inner thoughts and fears. In his pen, her role as a mother was paramount, especially her concern for the welfare of her dispersed children during their three years of captivity. It also included several references to “all-powerful providence” as the reason for Jemima’s perseverance and survival, as to be expected from a clergyman writing at the time.[10]

Both David Humphreys and Reverend Gay seized the opportunity to spin stories about their captives. Both writers wanted their work to provide “amusement” for readers. Humphreys was especially keen to promote a book about the life of a hero he had a major hand in creating as evidenced by his oversight of the publishing of at least seven editions of The Essay during his lifetime. With an obvious intention to sell copies, he also secured advertisements in the Connecticut Courant and Weekly Advertiser and the Connecticut Journal around the time The Essay was first released. The advertisements emphasized historical biography and romance, with language like “authentic account of an American Hero” and stories that surpassed the “bounds of credibility” and “astonishing fictions of romance.”[11]

As for Reverend Gay’s spin, soon after his account of Jemima Howe appeared in Belknap’s History of New-Hampshire, he took advantage of the ever-popular pamphlet, another distribution channel to gain readers. But that’s not all he did. After all, the good reverend’s work, as its title suggested, was authentic and true, thus implying that Humphreys’ The Essay was not. As Providence would have it, the reverend’s work followed that of Humphreys and so he had the advantage of reading an extract of The Essay in a Boston newspaper and reciting it to Jemima Howe. At first, she thought it was all true. But for reasons that Reverend Gay never explained, she changed her mind about the truthfulness of several of Humphreys’ stories.[12] With that information in hand, Reverend Gay countered Humphreys’ romantic tales.

Thus, the stage was set in the battle for readers between David Humphreys, a widely-read American poet, writer and “literary celebrity” of the time; and Reverend Gay, who was Jemima Howe’s local pastor, neighbor, and a poetic writer of “quaint epitaphs” and eulogies of his long-gone flock.[13]

Despite the undeniable facts about Putnam as a French prisoner of war in Quebec, especially a daring plot to escape with three other adventuresome characters—interesting stories in their own right—they were not included in Humphreys’ storyline.[14] Instead, he focused on Putnam’s willingness to jeopardize his own safety to protect Jemima Howe from her French masters’ repeated attempts to compromise her virtue.

In one romantic scene, Humphreys wrote that the young Frenchman was “fired to madness by the sight of her charms . . . forcibly seized her hand . . . declared that he would now satiate the passion which she had so long refused.” Mrs. Howe used “tears, those prevalent female weapons . . . while he . . . snatched a dagger, and swore he would put an end to her life.” She implored him to do so, but finally managed to escape from his clutches. Putnam rushed to her rescue, warning the persistent young man that he would “protect the lady at the risk of his life.” According to one literary critic, Humphreys’ version of the Putnam-Howe captivity narrative read like a “novel of seduction” rather than history or biography. Even today, reading about Putnam’s chivalry and fatherly relationship with Mrs. Howe’s young sons, it is easy to imagine that he, too, had not escaped the power of Mrs. Howe’s charms.[15]

Humphreys’ captivity narrative also served as partisan propaganda to affirm the shift from that of being collective captives of a tyrant king to a collective self-image as citizens of a nascent republic built on American soil. It was not an accident that Humphreys’ story had no British officials, officers, or regulars to support the colonial prisoners of war in Quebec. Even the French governor-general of New France, Pierre de Tigaud, Marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial, representing America’s war-time ally, negotiated an arrangement to release certain prisoners with Col. Peter Schuyler of New York, including Jemima Howe, three of her sons and Israel Putnam. Governor Marquis de Vaudreuil’s presence is palpable in Humphreys’ story and provides a stark contrast to the absence of British actors.[16]

In Humphreys’ pen, once Putnam and Mrs. Howe rediscovered their freedom, they became literary metaphors for the revolutionary sentiment and triumph over British assaults on liberty. By using this story to create Putnam as an early American heroic archetype, Humphreys could showcase the emerging nation’s political and cultural independence from Britain and put Israel Putnam and, to a lesser extent, Jemima Howe, on the map of America’s early literature and mythmaking.[17]

Humphreys’ competition was Rev. Gay, whose writing about Jemima Howe was not as accurate as his “genuine and correct” title claimed. From the very first word of his narrative, Reverend Gay is a co-author and editor interjecting his own comments into the story.[18]

As editor, Reverend Gay altered Jemima’s voice to embellish her story and exploit the growing popularity of this market. For example, after she was sold by her captors to a Frenchman named Joachim Saccapee and his son, who considered her their paid-for property, they subjected her to their “excessive fondness” and continuous advances. It was through Colonel Schuyler that the Marquis de Vaudreuil learned of her plight, chastised the father and ordered the son, an Army officer, from “the field of Venus to the field of Mars.”[19] This was a phrase a Harvard-educated editor would know and use, not one a frontier woman would likely know, let alone use.

To bolster the reverend’s truth-bearing title—and despite acknowledging that he had read only an extract of The Essay in a Boston newspaper much earlier—it is not until the very end of the narrative when Reverend Gay mentioned Israel Putnam and took umbrage with Humphreys’ “romantick and extravagant” tales, claiming that he was “misinformed” about the details.[20] For example, with the full support of Jemima, the reverend countered Humphreys’ story about the “amorous and rash lover” whose veins boiled at the thought of her such that “blood would frequently gush from his nostrils.” Humphreys detailed the obsession further, adding that the unrequited lover, who had now lost his senses, followed the newly released prisoners to Lake Champlain, jumped into the cold November water and swam after Jemima Howe’s boat, never to be seen again.[21]

Although Reverend Gay’s version of this story was toned down, it too seems questionable. He countered Humphreys’ story with his own and with the full support of his subject. He wrote that when Jemima was enroute from Canada to Albany, she met the young Saccappe while on a boat with Colonel Schuyler. The persistent man boarded, gave her some “handsome presents” and then departed in what appeared to be “tolerable good humour.”[22] There is no indication if she rejected his gifts, which would have made the story plausible given his recent threat to kill her with his dagger. It is hard to imagine how or why Saccapee would make such a dramatic shift to a more gentlemanly demeanor, especially after his prized possession was taken from him.

Reverend Gay continued with a story presumably told by Jemima. When she went to Canada after the French and Indian War to bring her daughter Submit back home, she again met the young Saccapee who showed her a lock of her hair and her name printed in vermilion on his arm. Reverend Gay never explained why Jemima, who claimed to need a “large stock of Prudence” to fend off the frequent encounters with the young man, would ever see him again. Although quick to point out Humphreys’ romantic tales, the reverend never explained how the persistent man obtained a lock of her hair or her reaction to seeing her name in bright red painted on his arm.[23]

Reverend Gay gilded the anti-Humphreys lily again, countering another of his misinformed tales. The reverend explained that Mrs. Howe had never been appointed, let alone considered, to be sent to England as her hometown’s agent to advocate for a local New Hampshire land claim being superior to that of a New York grant. On the other hand, Humphreys claimed she had been “universally designated” by her neighbors for the trans-Atlantic task. One often-cited expert on Indian captivity narratives has caustically noted that Humphreys’ claim was completely “bogus.”[24]

Interestingly, the Humphreys stories noted by Reverend Gay as romantic, extravagant, and misinformed were omitted from the version of The Essay that was included in the last edition of Humphreys’ Miscellaneous Works, dated 1804. Although we will never know with absolute certainty why Humphreys made these deletions, we can draw several well-founded conclusions. We know that Humphreys oversaw the publishing of this later work and made dramatic revisions throughout to accommodate new knowledge and the changing attitudes of readers. In this later edition of The Essay, he likely decided to bow to the competition in favor of a more fact-based, yet perhaps less commercially acceptable, story. This conclusion seems likely as the 1804 publication included a new footnote stating that these stories had come from Putnam himself and were omitted because “on further information, they appeared to be mistakes.”[25] Just perhaps, this further information came from a competitive ecclesiastical source.

The narratives of the two writers take different approaches to the literary genre of captivity narratives. Reverend Gay’s approach is a story of a frontier woman and her inner thoughts during captivity, a damsel in distress who is a victim of the wilderness. Although Jemima Howe shows signs of assertive behavior, she still must seek out men for assistance. The reverend’s story is about Jemima Howe and her concern for her family, reserving any mention of Putnam or criticisms of Humphreys until the end of the narrative.

On the other hand, Humphreys wove together a story about Putnam’s capture by Indians and his calm (and, thus, heroic) character while nearly being roasted alive with a second captivity tale that details his intriguing relationship with a melancholy and sentimental (and, thus, sympathetic) heroine. Humphreys’ interwoven stories also reflected the promise of optimism regarding what was then the western frontier and the courage and prowess of a newly emerging frontier hero, an American archetype. Humphreys’ work is closely aligned with the beginning of Romantic fiction in which the hero of his own Indian captivity narrative steps into another captivity scene to rescue a fair maiden.[26]

In retrospect, it is not surprising that Humphreys would take the approach he did with The Essay and have such success with it. One of his Yale peers and member of the Connecticut Wits, the poet and lawyer John Trumbull, created the mold for a successful Romantic narrative. In 1786, Trumbull published a popular, albeit pirated, version of Daniel Boone’s story published earlier by John Filson, a Kentucky surveyor and friend of Boone. Trumbull was obviously keen to sell a pamphlet about the increasingly popular western adventure that also included a female captive to cater to readers’ tastes for a sensational story. Both Humphreys and Trumbull featured their lead character as the prototype of the frontier hero, thus, placing them squarely in the early stages of American romantic fiction. Both writers, but especially Trumbull, likely far exceeded their wildest expectations with the numerous reprints of their popular stories.[27]

Long after these first stories about Jemima Howe and Israel Putnam, several additional works were written about the “fair captive.” The two most notable are a lengthy prose-like poem by Annie L. Mearkle published in 1937 and the more well-known historical novel by the prolific New England writer Marguerite Allis in 1941, Not without Peril. In true romantic form, Allis tells of Putnam and Jemima Howe parting ways after their release from French captivity, hardly able to speak as they hold back their tears, even the gregarious and usually outspoken Putnam. These writings, like those from the late Revolutionary era, continue to cloud an authentic account of the life of Jemima Howe, an indefatigable pioneer heroine and well-to-do widow who became a financial matriarch to her family and business partner of influential male neighbors and politicians, well worth knowing about for inspiration today.[28]

[1]Jane Strachan, “Jemimah Howe: Frontier Pioneer to Wealthy Widow,” Journal of the American Revolution, December 9, 2021, https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/12/jemima-howe-frontier-pioneer-to-wealthy-widow/.

[2]Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: “Women’s Sphere” in New England, 1780–1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 15.

[3]Gary L. Ebersole, Captured by Texts. Puritan to Post-Modern Images of Indian Captivity (Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 1995), 9–10.

[4]Frank Luther Mott, Golden Multitudes: The Story of Best Sellers in the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1947), 20, 303; Christopher Castiglia, Bound and Determined (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 107, 208n2.

[5]Greg Siemenski, “The Puritan Captivity Narrative and the Politics of the American Revolution,” American Quarterly, 42, no. 1 (March 1990), 35.

[6]David Humphreys, An Essay on the Life of the Honourable Major-General Israel Putnam (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2000), xxiii. This reprint was taken from the last published edition of The Miscellaneous Works of David Humphreys in 1804. Unless otherwise noted, all references to The Essay refer to the 2000 reprint. Edward Cifelli, David Humphreys (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1982), 76, 108.

[7]Ebersole, Captured by Texts, 160–164.

[8]Robert W. G. Vail, “Certain Indian Captives of New England,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 68, no. 3 (Oct. 1944–May 1947), (113–131), 126‒127, detailed publication history of Reverend Gay’s narrative.

[9]Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, Ed. Kathryn Zabelle Derounian-Stodola (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), which uses Bunker Gay’s text from A Genuine and Correct Account of the Captivity, Sufferings and Deliverance of Mrs. Jemima Howe (Boston: Belknap and Young, 1792), xxvi, 95.

[10]Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 98, 100.

[11]“David Humphreys to Jeremiah Wadsworth,” June 4, 1788 in David Humphreys, The Essay, 1–3, about the purpose and nature of his work; Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 97, for Reverend Gay “speaking” to Belknap in the opening of Mrs. Howe’s account; Frank Landon Humphreys, Life and Times of David Humphreys: Soldier—Statesman—Poet, ‘Belov’d of Washington’ (1917, repr., New York and London: Franklin Classics Trade Press, n.d.), 2:Appendix VI, 461–466; Connecticut Courant (Hartford), September 1, 1778, 1; Connecticut Journal (New Haven), September 3, 1788, 3.

[12]Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 94, 104.

[13]Cifelli, David Humphreys, 49, for the quotation “literary celebrity;” Abby Maria Hemenway, Vermont Historical Gazetteer (Brandon, VT: Published by Mrs. Carrie E. H. Page, 1891), 5:292, 309.

[14]For Putnam’s adventures in Quebec, see Robert C. Alberts, The Most Extraordinary Adventures of Major Robert Stobo (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 202–203; Simon Stevens, Journal of Lieut. Simon Stevens, from the Time of his being Taken, near Fort William-Henry, June 25th 1758 (Boston: Edes and Gill, 1760), 3–5.

[15]Humphreys, The Essay, 51–52; Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 93, for the quotation “novel of seduction;” Helen Hunt Jackson, Bits of Travel at Home (1878; repr., Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1909), 202–203.

[16]Siemenski, “The Puritan Captivity Narrative and the Politics of the American Revolution,” 36, 45.

[17]Ibid., 36, 45 and 52; Leon Howard, The Connecticut Wits (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1943), 270; Cifelli, David Humphreys, 74.

[18]Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 94–95.

[21]David Humphreys, The Essay on the Life of the Honorable Major-General Israel Putnam: Addressed to the State Society of the Cincinnati in Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1788), 80, quotations are from the original printing of The Essay in 1788.

[22]Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 104.

[24]David Humphreys, The Essay on the Life of the Honorable Major-General Israel Putnam: Addressed to the State Society of the Cincinnati in Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1788), 81–82, for the quotation “universally designated.” Derounian-Stodola, Women’s Indian Captivity Narratives, 104, 346n15.

[25]Howard, Connecticut Wits, 259; Cifelli, David Humphreys, 104; Roy Harvey Pearce, “The Significances of the Captivity Narrative,” American Literature 19, no. 1 (March 1947), 13; Humphreys, The Essay, 52, explaining the reason for the deletions.

[26]Ebersole, Captured by Texts, 160–164; Richard Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence, the Mythology of the American Frontier, (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press), 324.

[27]Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence, the Mythology of the American Frontier, 323‒325.

[28]Angela Marco [A. L. Mearkle], “Fair Captive, a Colonial Story” (Brattleboro, VT.: Stephen Day Press, 1937); Marguerite Allis, Not without Peril (1941; repr., Charlestown, NH: Old Fort No. 4 Associates, 2004).

Recent Articles

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Those Deceitful Sages: Pope Pius VI, Rome, and the American Revolution

Recent Comments

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Thank you Eric! I should say that I have enjoyed your work...

"Trojan Horse on the..."

Great article. Love those events that mattered mightily to participants but often...