This story begins five weeks after Gen. John Burgoyne’s army forced the Americans to abandon positions on Lake Champlain in July 1777. On August 12, Gen. Benjamin Lincoln wrote to Washington telling him, “I am to return with the militia . . . to the northward, with a design to fall into the rear of Burgoyne.”[1] A few days later, Lincoln met with Generals Horatio Gates and George Clinton at Gates’ camp nine miles north of Albany where the officers worked out goals for the expedition. The mission would be to harass Burgoyne’s army in a manner that “will most annoy, divide, and distract the enemy.” The corps would also look to protect against foragers and to restrain Loyalists. Given considerable discretion as to how to conduct the mission, Lincoln needed to take care to keep his force intact and in a position to attack the enemy’s flank if they retreated.[2]

Three days later, several Massachusetts militia regiments received orders to gather in Bennington, Vermont. Lincoln told them to “Leave behind all our heavy Baggage & to Take one Shift of Cloaths only.” A high level of mobility being necessary, the little army would travel light with everyone living out of their blanket rolls, tumplines, and knapsacks.[3]

Lincoln felt satisfied with the plan: “in the eligibility of it I am daily more confirmed.”[4] Gates apparently did not feel quite so assured when he wrote to Lincoln on August 29, “I wish once more to see you here, that you, & I, [Gen. Benedict] Arnold, [Gen. John] Glover, & [Col. Daniel] Morgan, may settle a Fixed Plan for Our Future Operations.” Gates wanted Gen. John Stark to attend the meeting but that would have left the forces around Bennington without a commander so he told Lincoln to ask Stark for his opinion.[5]

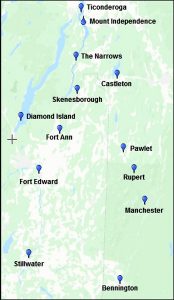

The officers decided that the base for Lincoln’s operation would be Pawlet, Vermont. The town sat thirty-five miles north of Bennington with access from the north and west limited to two roads between steep, high mountains thereby affording protection from British attack. Circumstances placed Pawlet midway between Burgoyne and his primary supply depot at Ticonderoga, with the posts guarding that supply line just a few miles to the west.[6]

By early September Lincoln had assembled over 2,000 men. Most of the troops came from Massachusetts militia regiments called up for three months of service from the counties of Berkshire, Hampshire, Worcester, Middlesex, and Essex. Recently-formed Vermont sent Col. Samuel Herrick’s rangers and Peter Olcott’s militia. For Continentals, Lincoln had elements from Seth Warner’s Green Mountain Boys and Benjamin Whitcomb’s Independent Corps of Rangers. Some of the Massachusetts men came on horseback, each horse carrying a load of flour or ammunition. These horsemen would serve as messengers allowing for a quick exchange of letters between officers scores of miles apart.

British Gen. Henry Watson Powell commanded 1,000 men at Ticonderoga, Mount Independence on the opposite side of Champlain’s South Bay, and posts on Lake George. The majority came from the British 53rd Regiment and the Brunswick (German) Prinz Freidrich Regiment. The Brunswickers and three weak companies of the 53rd occupied Mount Independence. The remaining regulars, some sailors and artificers, a few score Canadians, and a contingent of men from various other regiments manned the posts around Ticonderoga and Lake George. A large number of the men, including Powell, suffered from the ague (malaria) with the sickest housed in the hospitals with the wounded.[7]

As Lincoln formed his army, he discovered a problem with ammunition. General Heath had forwarded a “good supply” but the militia did not come with as many cartridges as Lincoln had been led to believe.[8] Further, a supply sent from the magazines at Springfield and Albany had not “been of a size suitable for the muskets.”[9] The shortage “fills me with anxiety least we suffer from a want of that indispensably necessary article.” He wrote for an additional supply and could only hope for its arrival on time.[10]

In spite of desiring more troops and ammunition, Lincoln moved ahead with the plan. He marched his brigade twenty miles north to Manchester and dispatched a party of rangers to Pawlet to secure the area. The rest of the troops began their advance on September 8.[11] Students of the Burgoyne campaign may note that both Lincoln and Gates began their moves northward on the same day. It is likely they had planned this as Gates wrote, “Having prepared every thing in Concert with General Lincoln, for the March of the Army, I left Van Schaack’s Island on Monday . . . General Lincoln, and General Stark, are marching by Manchester, and Pawlet.”[12]

Lincoln’s brigade did not move the entire distance to Pawlet. Instead, they stopped after eleven miles in Rupert, “att which Town their is a Rode over the Mountain to fort Edward,” Burgoyne’s forward supply base. They continued the march the next day and, “Arived att Pollett 4 Miles from Ruepert & Encampd. . . in a Wood by the Side of the Rode facing West.”[13] Tents had been left behind so shelters consisted of bowers and lean-tos made of brush and branches.

There is some question as to the location of this encampment. Popular history supposes the men camped within or close to the village of Pawlet but that is six miles, not four, from the Rupert camp. Further, the immediate terrain around the village has no area to conveniently camp 2,000 men together. Conversely, four miles from Rupert the Mettawee River intervales could easily accommodate a large camp. In addition, early maps show a road headed west from the intervales that is now just a trace through the countryside but, back then, joined the previously-mentioned road to Fort Edward. Lincoln likely camped at road junctions to facilitate a quick march west should his men be needed to face Burgoyne. The road west out of the village of Pawlet first ran north before turning west and added five miles to the march to Fort Edward.

On September 12 Lincoln and his officers created three 500-man detachments. One party under Berkshire County’s Col. John Brown would attack Fort Ticonderoga while another under Essex County’s Col. Samuel Johnson would harass Mount Independence as a diversion. To protect the rear of these detachments, the third party commanded by Col. Benjamin Woodbridge of Hampshire County would take Skenesborough and move south. Lincoln with Col. Benjamin Symonds’ Berkshire County militia would remain behind to guard Pawlet.[14]

The men “Received orders to Bake 4 days allowance of Bread” and the first elements began their march in the late afternoon of the same day. Once they reached Castleton twenty miles north, progress stalled—Seth Warner’s men and two of Brown’s own companies had not yet arrived. Worse yet, supplies from Bennington had not arrived and they could not move without them.[15]

The detachments marched again on the 15th. Johnson’s group reached Lacey’s Camp at the north end of Lake Bomoseen and then moved toward Mount Independence.[16] Woodbridge’s force followed the road west to Skenesborough. Brown’s detachment had, by far, the most difficult march. They followed the road west for about five miles but then had to travel northwest toward The Narrows on South Bay, “over an uncultivated wilderness seldom exceeded for its roughness.”[17] They then had to cross the water before continuing their march another ten miles through more wooded, mountainous terrain to The Landing at the north end of Lake George.

Back at Pawlet, other troops continued to arrive. With 700 of these men, Lincoln headed for Skenesborough to assist that detachment’s move south. Woodbridge, however, found that the posts guarding Burgoyne’s supply line had been abandoned. He settled in at Skenesborough and sent a party to help Brown cross The Narrows.[18]

Gates wrote to Lincoln on September 17: since the British had severed their connection to the north thereby achieving the primary goal of Lincoln’s mission, “would it not be right, you take some Station near or upon the North [Hudson] River? . . . your posting Your Army somewhere in the Vicinity of mine [at Stillwater], must be infinitly Advantageous to Both . . . it would embarrass [Burgoyne] exceedingly.”[19] While Gates certainly intended his words to be taken as orders, the phrasing allowed Lincoln some discretion that he would exploit.

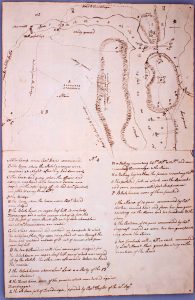

That same day, Colonel Brown arrived at the heights south of Sugar Hill (renamed Mount Defiance by the Americans), “where I made what Discoveries I could of the Situation of the Enemy at the several Posts.” Johnson’s men also arrived at Mount Independence. Both parties succeeded in moving close to their objectives because “it was impossible for [the defenders] to send out patrols for any distance, the woods being so thick and extensive.”[20]

At daybreak on the 18th Brown attacked Sugar Hill and The Landing.[21] Encountering minimal resistance, Capt. Ebenezer Allen’s company overran the battery on Sugar Hill. At The Landing, the British fired a few futile shots but Brown’s men quickly took control, one British officer writing, “being so far favour’d by a fog that they had surrounded, and got amongst our marquees by the time they were discover’d.” A party under Major Wait moved on to the bridge near the falls of the LaChute River where the guard, mistaking them for Canadians, allowed them to cross.[22]

Once across the bridge, parties spread out. The defenders at the mills never fired a shot—the falls being so noisy, they never heard anything from the other fighting. One group of Wait’s men moved to a house and barn where they captured the guards and freed prisoners used as laborers who “come out of their Holes and Cells with Wonder and Amazement.”A party of Seth Warner’s men attacked a blockhouse but had to bring up a cannon to force a surrender. Pressing on, Wait’s men took control of the undefended French Lines. In a short period of time, Brown’s detachment had captured most of the outworks of Fort Ticonderoga. He immediately sent a demand for the surrender of the fort and Mount Independence but “receiv’d a Manly denial from General Powel.”[23]

Colonel Johnson launched an attack on Mount Independence. His men drove in the pickets but failed to make any inroads against the defenses. Powell had “presumed that the Provincials might soon attempt an attack” and cautioned his troops to be ready. The garrison “remained fully dressed as a precautionary measure and ready to move out.” When the men on the Mount heard the clamor raised by Brown’s attack, they occupied their alarm posts quickly.[24]

In addition to a prepared garrison, the Mount’s attackers faced a defensive system consisting of three levels. Abbatis (felled trees with sharpened branches facing the enemy) made up the first level at the base of the slopes. Mid-way up, the second entailed artillery batteries supported by infantry behind stone and log walls. The third level on top of the Mount consisted of blockhouses, fortified houses, artillery, and more walls.[25] In addition, ships had been positioned on the lake so that their guns could sweep the ground below the Mount.[26] Johnson had little chance of taking the position.

Brown felt that “my success has hitherto answered my most sanguine expectations.” It had cost three or four killed and five wounded. In the first minutes of the raid, his men had taken 293 captives, 200 bateaux, seventeen gun boats, one armed sloop, a few cannon, and numerous small arms. Over 100 prisoners had been freed and armed. A large amount of plunder also fell into their hands but clothing made up most of it. Only minimal amounts of desired ammunition and provisions had been found.[27]

September 19 had little of the previous day’s turmoil and excitement. On the Ticonderoga side, the captured cannons began firing on the fort. On the other side of the lake, “Except for much small arms and cannon fire, nothing much happened.”[28] The two commanders thought of joining forces in an assault on Mount Independence but decided that taking only one side of the lake would not be sound.

Brown wrote two letters to Lincoln that day. In the morning, he recounted what had happened and asked for 200 to 400 reinforcements not for an assault, but for help moving the large quantity of plunder.[29] Later in the day, he changed his tone saying the reinforcements would be used to counter armed vessels that had appeared on Lake George and for an attack on the fort. Almost as an aside, he asked to have them bring provisions.[30]

Although not part of the plan, Brown wanted to capture Ticonderoga and Mount Independence. Conditions, however, made it impossible. The cannons firing on Ticonderoga had little effect and the needed provisions and ammunition had not been found. Worse yet, intelligence reported British reinforcements coming. With insufficient numbers to storm the fort along with the time constraints imposed by limited supplies and enemy reinforcements on the way, Brown held little expectation of succeeding: “It is most certainly out of my Power to cast the Enemy from that place, should they chuse to keep it.”[31]

Brown might have thought differently if he had known only thirty men defended the fort. Powell, with his own numbers problem, worried about a coordinated attack on both posts and reinforced his positions with men from the hospitals. He even went to the extent of positioning provision boats on the water to give the impression of additional naval firepower.

Powell need not have worried. To augment his numbers, over 100 Brunswickers arrived by boat. Further, back in Pawlet, a change in plans had come about. Gates wrote on September 19 reinforcing his earlier letter asking Lincoln to move south. In sterner language, Gates said Lincoln ought to be at Stillwater and told him to take position with 500 or 600 men on the east side of the Hudson. In spite of superior numbers, Gates still had concerns about his situation and “Wish he [Lincoln] may get in before it’s too late.”[32]

Lincoln responded the next day. He wrote that as soon as he had received the earlier letter, he ordered the 700 men moving toward Skenesborough to act “agreeable to your orders.” He also wrote that Woodbridge’s party would remain to cover the withdrawal of Brown and Johnson, now under the command of newly-arrived Gen. Jonathan Warner. Lincoln also noted that “The fate of Ticonderoga is yet undetermined” and did not think Gates wanted to recall those troops.[33]

Late on September 20, Brown penned a letter to Lincoln. He had just learned from General Warner of Gates’ recent orders which put any further offensive activity out of the question. To retreat immediately, however, would be impractical and result in the loss of the prisoners and the plunder. He would organize a withdrawal the next day.[34]

Brown’s letter crossed paths with one sent from Pawlet. Lincoln wrote he would be joining Gates but “General Warner & you must set your own judgments with respect to attacking ye enemis lines continuing ye Siege or retiring.” Gen. Jacob Bayley had a store of supplies at Castleton, and Woodbridge still waited at Skenesborough.[35]

The decision to leave had already been made. Warner and Johnson would retreat via The Narrows and Brown would move up Lake George with the intent to attack Diamond Island where the British had stored their baggage. The two detachments abandoned their positions on September 21-22 and Warner, with some of Johnson’s troops, arrived at Castleton on the 23rd.

Brown took longer. After burning some storehouses and other structures (but, for whatever reason, leaving the blockhouses),[36] he and his men set out on the 22nd using a sloop mounting three cannons, two gun boats each with one cannon, and 400 men in bateaux.[37] The weather delayed them for a day but the flotilla finally attacked Diamond Island on the morning of the 24th.

They did not achieve any surprise: a prisoner had escaped and warned the garrison. The attackers attempted two landings but the sloop and another boat received so much damage that they broke off the attack after two hours. Two men died, two more received mortal wounds, and several others had lesser wounds. The battered fleet limped into a bay on the east shore where the men burned the boats and whatever they could not carry. Brown left the seriously wounded men with inhabitants and the detachment trudged away to Skenesborough.[38]

The final events related to Brown’s Raid took place over the next few days. Almost all of the troops returned to Pawlet by the 28th and either received discharges or moved on to join Lincoln and Gates at Bemis Heights.[39] At the same time, questions about the plunder arose. Because they had captured it, Brown’s men felt entitled to all of it and, indeed, Brown had promised it to them. Men in other detachments felt they should receive a share. General Warner begged off the question, writing, “I rather decline determining the Matter—should be glad your Honour [Lincoln] would do it.” Those who had been discharged waited in Pawlet for a ruling.[40]On October 2, Gates wrote that whoever captured the plunder had sole rights to it.[41]

In an interesting comment made to an unknown recipient, Brown wrote that he was happy to present the recipient a “Continental Standard” retaken at Ticonderoga on September 18. He “conceived the Colours to have belonged to an armed vessel” until he opened them. With tongue most firmly imbedded in his cheek, he wrote, “Please to Present my Compliments to those Gentlemen who in their hurry slipt off and forgot them.”[42]

What impact did Brown’s Raid have on the Burgoyne campaign? The detachments seized all of Ticonderoga’s outworks, bottled up the garrisons of both posts, and captured 330 of the enemy, over 200 boats, numerous carriages and harnesses, cattle, horses, cannon, arms, ammunition, clothing, and other stores. They also freed and armed 118 prisoners. Brown’s men sent the captives to prisons, destroyed the carriages, harnesses, and boats, killed or released the animals, and took with them a considerable amount of stores before burning the rest.

The besieged garrison reported other effects of the raid. Brunswick Lt. August Wilhelm Du Roi wrote, “Not only was the transportation of supplies to our army very difficult on account of the attacks made by the enemy, but all communication between our armies was cut off.”[43] In addition, Burgoyne’s reinforcements from Canada under Gen. Barry St. Leger could not move beyond Ticonderoga. Powell refused to let them go for fear of losing his posts should Brown and Johnson return. Besides, all the carts and harnesses necessary to transport St. Leger’s baggage and equipment had been destroyed in the raid.[44] With the failure of Burgoyne’s campaign, Powell and his men abandoned Mount Independence and Ticonderoga on November 8. It would seem Brown’s Raid seriously impacted the campaign.

A closer look, however, reveals an alternative conclusion. From the beginning of the campaign, Burgoyne faced major problems: he left Canada with limited supplies and inadequate transport. By early August, he realized that the plan to compensate for those deficiencies by foraging had proven near impossible and that he still had a long way to go before raw autumn weather arrived. On August 15—before Lincoln and Gates met to plan the raid—Burgoyne began to shift all necessary stores from Ticonderoga to his army. Brown’s men found limited ammunition and few provisions because anything of value had been taken away.

Nor did Brown’s Raid truly threaten the supply line. Once the valuable supplies had been gathered, Burgoyne abandoned the long, tenuous connection north and resumed his advance on September 13—before Lincoln’s detachments had even been formed.

What of the reinforcements stalled at Ticonderoga? Burgoyne himself answered that question when he wrote that the men would have arrived “in time to facilitate a retreat, though not in time to assist my advance.”[45] Facing an entrenched enemy three times his numbers, Burgoyne would have suffered some degree of defeat regardless of Brown’s activities.

It would be uplifting to think of Brown’s Raid as having a significant influence on the Burgoyne campaign. In reality it did not. At the time of its inception, conditions made it a worthwhile plan but, by the time of its implementation, those conditions had changed sufficiently to negate its value. With or without Brown’s Raid, 1777 most likely would have ended the same.

[1]Benjamin Lincoln to George Washington, Stillwater, New York, August 12, 1777, Correspondence of the American Revolution, ed. Jared Sparks (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1853) 1:423.

[2]Lincoln to John Brown, Pawlet, Vermont, September 12, 1777, Correspondence, 2:525.

[3]Ralph Cross, “The Journal of Ralph Cross, of Newburyport, Who Commanded the Essex Regiment, at the Surrender of Burgoyne, in 1777,” Joseph Williamson, ed.,The Historical Magazine 7, Second Series (January 1870): 9.

[4]Lincoln to Horatio Gates, Bennington, August 29, 1777, Horatio Gates Papers, 1726-1828, microfilm, Baker-Berry Library, Dartmouth College, reel 5, frame 335 (Gates). Due to COVID restrictions as of this writing, visitors to the library must be sponsored by a member of the Dartmouth community. This author would like to thank Professor Colin Calloway for agreeing to be his sponsor.

[5]Gates to Lincoln, August 29, 1777, Gates, 5:355. Direct primary source evidence that the meeting took place has not been found but Rev. Enos Hitchcock wrote that Lincoln attended a funeral and the hospital in Gates’ camp on September 1. “Diary of Enos Hitchcock, D. D., A Chaplain in the Revolutionary Army,” Publications of the Rhode Island Historical Society, New Series, 7 (1899): 151. Further, comments in other sources hint that the meeting did happen.

[6]While sitting equidistant between Ticonderoga and Burgoyne may seem to be a consideration in the choice of Pawlet as a base of operations, this is probably not the case. No primary sources mention this fact and as soon as Burgoyne abandoned the posts guarding his communications back to Ticonderoga, Gates called for most of the troops at Pawlet to join him. The location’s value rested in its proximity to the posts along that line of communications, not to its endpoints.

[7]Powell to Carleton, Ticonderoga, September 18, 1777, Fort Ticonderoga Bulletin 7, No. 2 (July 1945), 29-30.

[8]Lincoln to Gates, Bennington, September 4, 1777, Correspondence, 2:524.

[9]Lincoln to Gates, Pawlet, September 11, 1777, Correspondence, 2:525.

[10]Lincoln to Gates, September 7, 1777, Gates, 5:502.

[12]Gates to John Hancock, Stillwater, September 10, 1777, Papers of the Continental Congress, Microfilm, National Archives, Washington, D.C., reel 174, item 154, 1:256 (PCC).

[13]Cross, “The Journal of Ralph Cross,” 9. Several period items have been found in the area of Rupert hinting at its occupation by Lincoln’s force.

[14]Lincoln to Council of Massachusetts, Pawlet, September 23, 1777, Correspondence 5:528.

[15]Cross, “The Journal of Ralph Cross,” 9. Brown to Lincoln, Castleton, Vermont, September 14, 1777, in “Col. John Brown’s Expedition Against Ticonderoga and Diamond Island, 1777,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Society, vol. 74 (October 1920), 285 (NEHGR).

[16]Cross, “The Journal of Ralph Cross,” 9. People knowledgeable about the Battle of Hubbardton will recognize this as the place the British force camped the night before the battle.

[17]Lemuel Roberts, Memoirs of Captain Lemuel Roberts (Bennington, VT: 1809), 54. As a participant, Roberts gives a detailed account of the action at the start of the raid.

[18]Lincoln to John Laurens, Boston, February 5, 1781, Correspondence 2:534. Roberts, Memoirs, 53.

[19]Gates to Lincoln, Bemis Heights, September 17, 1777, Gates, 5:659-60.

[20]Lieutenant August Wilhelm Du Roi, Journal of Du Roi the Elder, trans., Charlotte Epping, Americana Germanica, No. 15 (University of Pennsylvania: 1911), 102.

[21]Dr. Matthew Keagle, Miranda Peters, and Tyler Ostrander at Fort Ticonderoga provided prompt, generous, and friendly assistance with my research providing access to several primary sources including the Starke map.

[22]Thomas Hughes, A Journal by Thos: Hughes (1778-1789) (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1947), 12-13.

[23]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 18, 1777, NEHGR, 285.

[24]Ensign Julius Friedrich von Hille, The American Revolution, Garrison Life in French Canada and New York: Journal of an Officer in the Prinz Friedrich Regiment, 1776-1783, ed. and trans. Helga Doblin and Mary C. Linn (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993), 78.

[25]Jess Robinson, Geospatial Mapping of the Landward Section of Mount Independence Project: A Cooperative Project between the American Battlefield Protection Program and the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation—Grant #GA-2287-16-020 (2018), 8.

[26]The ships may not have been able to provide much support. Lieutenant John Starke commanding the Mariawrote Carleton that the guns had been taken on shore, likely in preparation for closing up the ships for the winter. See Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1986), 9:935.

[27]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 18, 1777, NEHGR, 286.

[29]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 19, 1777, NEHGR, 286-7.

[30]Brown to Lincoln, September 19, 1777, New York Public Library, digital collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bb266ec4-a678-320d-e040-e00a180616a6.

[31]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 19, 1777, NEHGR, 286-7.

[32]Gates to Lincoln, Bemis Heights, September 19, 1777, Gates5:685. “General John Glover’s Letterbook,” Essex Institute Historical Collections, Salem, MA, v112, issue 1 (January 1976), 43.

[33]Lincoln to Gates, Pawlet and Castleton, September 20, 1777, Gates, 5:700, 703-4.

[34]Brown to Lincoln, September 20, 1777, NEHGR, 287-8.

[35]Lincoln to Brown, Pawlet, September 21, 1777, NEHGR, 288-9.

[37]Brown to Lincoln, Lake George Landing, September 20, 1777, NEHGR, 287-8.

[38]Brown to Lincoln, Skenesborough, September 26, 1777, NEHGR, 289-90.

[39]Warner to Lincoln, Pawlet, September 30, 1777, NYPL, digital collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bb4ebb8a-0c7e-c85e-e040-e00a18063bc4.

[40]Warner to Lincoln, Pawlet, September 28, 1777, NYPL, digital collections, digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/bf8807d0-5634-7928-e040-e00a180667c6.

[41]Lincoln to Brown, October 2, 1777, NEHGR291.

[42]Brown to ?, Pawlet, October 4, 1777, NEHGR292-93. The “armed vessel” comment makes one wonder how those colors differed from others? Size? Design? Brunswick surgeon J. F. Wasmus noted on July 3, 1777, seeing a “white flag with 13 stars and 13 red stripes” hoisted over Mount Independence. Could this have been the flag Brown found?

[44]Allan MacLean to Carleton, Ticonderoga, September 30, 1777, Fort Ticonderoga Bulletin 7, No. 2 (July 1945), 33.

[45]John Burgoyne, A State of the Expedition From Canada, as Laid Before the House of Commons (London: J. Almon, 1780), 15.

4 Comments

These Germans were sent over the Altlantic and through Canada. Then the army they were part of, left them in the wilderness. The Americans lived in the general area and were at home fighting in dense woods and the cold. Its a wonder the Germans did not surrender.

British command in the northern theater never abandoned the German troops. At Ti before Brown’s Raid, the British 62nd and, at the time of the raid, the 53rd served alongside them and they retired to Canada together. In Canada, British and German troops constantly served together–maybe not always on the best of terms but together, nonetheless.

As for woods and cold, remember that these men came from northern Europe with geography and climate not that different than the northern theater. In reading German accounts, its not the woods or cold that they complain about–it’s the bugs and snakes.

As for surrendering, they considered the “rebels” to be just that and to be the enemy. No soldier wants to surrender to the enemy. In their case, once the Germans became more familiar with life in North America, many of them did cross the lines.

Nice job Michael. Was Brown acting under a Continental commission or on behalf of Massachusetts?

The disposition of the plunder Brown took is another curiosity of mine. Did Vermont get anything?

Thanks, Brian.

Brown had command of the 3rd Regiment, Berkshire County, MA, militia. I don’t think he ever received a Continental commission. He died at Stone Arabia in 1780.

I have to admit I have not done much research into the final disposition of the plunder and, so, can’t answer your question. I do know that most, if not all, went to Bennington before Gates made his decision on who should receive it. A secondary source indicates that Vermont did receive/keep some of it. That’s a subject for further looking.