After his exploits during the French and Indian War, Robert Rogers (1732-1795) was indisputably the most famous military leader born in the thirteen colonies; however, he played only a cameo role in the Revolution because both the British and American commanders-in-chief, Thomas Gage and George Washington, not only scorned him but actually arrested him for treason. Rogers’ self-promotion, his financial debts, his indifference to the politics of the times, and his penchant for alcohol all contributed to his demise, but he was far from the only leading man of his day to suffer these faults.

Rogers’ humble roots in the New Hampshire wilderness, combined with his daring escapades, inspiring leadership, and courage under fire fueled a steady stream of publicity in the burgeoning broadsheets of the day. After the First Battle on Snowshoes in 1757, the Boston Gazette blazed: “The brave Rogers is acquiring glory to himself in the field and in some degree recovering the sunken reputation of his country.”[1] When Rogers straggled back to Crown Point in 1759, barely alive but victorious from his raid on the Abenaki village of St. Francis deep inside the Canadian wilderness, the Boston Weekly Newsletter headlined: “What do we owe to such a beneficial Man? And a Man of such an enterprising genius?”[2] After he accepted the French surrender at Detroit in 1760 and returned east, the New Hampshire Gazette boomed: “As soon as the arrival of the Gentleman was known, the people here [Philadelphia] . . . immediately ordered the bells to be rung.”[3] Of course, the headlines glossed over the rumors of scalpings, prisoner executions, cannibalism, and massacres that earned Rogers the respect of the Indigenous warriors as well as the Abenaki nickname Wobomagonda, White Devil.[4]

Unfortunately, Rogers borrowed heavily (roughly $200,000 in today’s currency) to recruit, train, and outfit his regiment, aptly nicknamed Rogers’ Rangers. These debts would force him away from the American scene for much of the next fifteen years, essentially crippling him for the rest of his life. When Parliament passed the Stamp Tax in March 1765, Rogers was in London evading his creditors while also hoping to raise the funds to repay them. Accordingly, he missed the virulent debates in the colonies that led the Crown to rescind the hated tax a year later.

While in London, he self-published his Journals in 1765, followed by an encyclopedic Concise Account of North America shortly thereafter; both became “best-sellers.” The longest chapter by far in Concise Account is entitled “Customs and Habits of the Indians.” Throughout, the author conveyed both detailed knowledge and great respect: “Avarice is unknown to them . . . they are not actuated by the love of gold . . . [their] great and fundamental principles are . . . that every man is naturally free and independent; that no one . . . on earth has any right to deprive him of his freedom and independency and nothing can compensate him for the loss of it.”[5] The Indigenous believed that land, if it was “owned” at all, belonged to the tribe, not the individual, a far cry from the rapacious approach of the British. Most notably, Sir William Johnson, Secretary of Indian Affairs and Gage’s mentor, personally owned hundreds of thousands of acres making him the second largest landowner (lagging only William Penn) in the colonies by 1770.

Also in Concise Accounts, Rogers boasted: “Certain I am that no one man has traveled over and seen so much as I have done.”[6] In fact, he dreamed of traveling further—all the way across the continent to the Pacific Ocean, if he could get funding. Given the sorry state of the Crown’s balance sheet after the Seven Years War, the likelihood of receiving cash upfront was low, but the government was offering a 20,000 pound reward upon discovery of the fabled Northwest Passage.[7]

On October 16, 1765, Rogers had the honor of an audience with King George III at St. James Palace. In a tone-deaf move befitting royalty, King George not only appointed Rogers commandant of Fort Michilimackinac, the Crown’s westernmost outpost in North America, but also requested Thomas Gage, who held a longstanding grudge, to reimburse Rogers for past expenses. Gage would be apoplectic when the King’s directive reached New York, immediately convening a commission to review Rogers expenses, delaying compensation yet again. As galling, the famous Rogers would now be in position to challenge Johnson as the Crown’s primary liaison with the powerful Indigenous tribes out west who were critical to the supply of fur pelts that fueled Johnson’s trading and real estate empire.

While revolutionary sentiment boiled in the eastern seaboard cities of the colonies, Rogers was at Michilimackinac, planning his expedition to seek the Northwest Passage and again borrowing heavily to do so. Gage and Johnson plotted as well, arresting Rogers for treason on trumped up charges in December 1767 and keeping him in chains for most of 1768. A court martial acquitted Rogers on all counts in October 1768 but Rogers’ name was forever stained.[8] Furthermore, Gage did not reinstate Rogers to his command or even give him permission to travel until March 1769.

More heavily in debt than ever, Rogers returned to London, seeking to restore his reputation and fortune at King George’s court. Accordingly, he was absent from the colonies when British regulars fired into a crowd of Bostonians outside the customs house in March 1770, the shots that stoked the flames of Revolution. After waiting three years while Rogers unsuccessfully pleaded his case, Rogers’ creditors finally had him committed to debtor’s prison on October 16, 1772.[9] It would be his home for the next two years, isolating him from the incendiary Boston Tea Party in December 1773 and Parliament’s response, the four Coercive (Intolerable) Acts, in the spring of 1774.

While Rogers rotted in prison, Gage, son of a First Viscount, and George Washington, well-ensconced in Virginia society after his marriage to Martha Custis in 1759, renewed their acquaintance in New York, having served together under Gen. Edward Braddock during the French and Indian War. Needless to say, neither Gage nor Washington could come close to matching Rogers’ accomplishments during this global conflict, yet both “gentlemen” emerged in far superior positions for advancement than the backwoodsman with an affinity for the Natives.

After the ambush on the Monongahela River in July 1755, Gage, a lieutenant colonel at the time and commander of the British vanguard, was publicly criticized by Robert Orme, Braddock’s aide, for “falling back in great confusion” when he should have pushed forward. Gage denied the accusation, flipping the blame back on Braddock. Other accounts noted that Gage fought well, albeit in covering the pell mell British retreat.[10]

Gage’s hesitancy was again visible in in 1758 during the first, disastrous assault on Fort Ticonderoga under Gen. James Abercrombie as well as in 1759when he waited for reinforcements rather than attack Fort Galette in Canada, earning the ire of his superior Lord Jeffrey Amherst. Amherst essentially demoted Gage to the back of the formation in favor of Rogers’ Rangers during the second, and successful, siege of Fort Ticonderoga later that year. Gage, however, enjoyed the last laugh as he was promoted to commander-in-chief of North America in 1763 after Amherst was recalled following Pontiac’s Rebellion.

The start of the French and Indian War was no more flattering for Washington. He blundered into battle at Fort Necessity in 1754, and, accordingly, was relegated to a volunteer role in the 1755 campaign. Nevertheless, he rallied the fleeing redcoats after Braddock fell mortally wounded. He later noted: “The Virginians behaved like men and died like soldiers . . . [unlike] the dastardly behavior of the English.”[11]

Despite this scathing critique, Gage complimented Washington: “I shall be extremely happy to have frequent News of your Welfare, & hope soon to hear, that your laudable Endeavours, & the Noble Spirits you have exerted in the Service of your Country; have at last been crowned with the Success they merit.”[12] The Boston Gazette could only pay Washington a backhanded laurel when he visited Massachusetts Gov. William Shirley seeking an officer’s commission in 1756, calling Washington “a gentleman who has a deservedly high reputation of military skill, integrity, and valor, though success has not always attended his undertakings.”[13] After Washington’s petition was again rejected, he retired to life in Virginia in 1758, captaining its militia most commendably for three years before settling into the life of a prosperous planter, devoted husband, and local politician.

Through 1773, Washington conducted his business as appropriate for a well-heeled colonist in the British Empire. Upon visiting New York to install his stepson, Jackie, at King’s College, he stopped at the Kemble estate in New Jersey, family home of Gage’s wife Margaret, for tea, attended a dinner in the city honoring Gage on May 27, and dined personally with the commander-in-chief on the 30th.[14] Over the course of the year, Washington worked through British government channels to expand his personal landholdings out west, noting to his surveyor: “no time should be lost in having them surveyed, lest some new revolution should again happen in our political System”[15] and petitioning Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s royal governor, for more acreage.

By 1774 Washington’s sympathies had become more radical. He noted in a July letter to his friend William Fairfax: “Are not all these things self-evident proofs of a fixed & uniform Plan to Tax us? If we want further proofs, does not all the Debates in the House of Commons serve to confirm this? and hath not Genl Gage’s Conduct since his arrival . . .exhibited unexampled Testimony of the most despotic System of Tyranny that ever was practiced in a free Government.”[16] In September, Washington embarked for Philadelphia as one of Virginia’s delegates to the Continental Congress; his interest in land, particularly his own land, never subsided as his letters home throughout his military service would attest.

In July 1774, the tide also began to turn in Robert Rogers’ affairs when Sir William Johnson passed away from natural causes. Shortly thereafter, Rogers was released from prison, albeit penniless. While he still collected his military pension, King George prohibited him from obtaining any actual command as retribution for a lawsuit Rogers had filed against Gage, who was still in favor at court.[17] Rogers focused instead on resurrecting his dream of exploring the Northwest Passage but, unsurprisingly, could only secure lukewarm support among his contacts in Parliament.

Fortunately, as the rebellion in Massachusetts surged, Gage’s star dimmed. Unlike Monongahela, Ticonderoga, and Galette, Gage was in charge now and could not pass the blame upward. His inability to curb the Sons of Liberty was public for all to see, earning him the nickname “the old woman.”[18] In April 1775, Gen. William Howe sailed from London ostensibly to assist Gage, but, in reality, to replace him.

Rogers scraped together enough funds to embark for North America in June 1775, shortly after news of the battles at Lexington and Concord had reached England.[19] Was he simply going home, or looking for some way to plunge into the fight, or returning to Michilimackinac and the western frontier? Rogers left no written record of his intentions.

After docking in Baltimore in August, Rogers trudged up to Philadelphia to renew old contacts and assess the political situation. Upon arriving, he was greeted with an interrogation by the Committee of Safety, not the ringing of bells. He was able to secure a meeting with John Adams, who wrote: “The famous Partisan Major Rogers . . . thinks we will have hot Work, next Spring. He told me an old half Pay Officer, such as himself, would sell well . . . when he went away, he said to Sam Adams and me, if you want me next Spring for any Service, you know where I am, send for me. I am to be sold.”[20] In the meantime, Rogers assumed the role of private citizen with landholdings and family up north; his commission in the British Army, his only source of income, proved an anchor around his neck.

After a month of pleading with Congress, Rogers finally received a pass to travel, providing he agreed not to scout or bear arms for the British. He journeyed next to New York, meeting with Gov. William Tryon to confirm his land grants, then to Albany to visit his brother, and finally to New Hampshire to see his wife and son after a five-year hiatus.

En route, Rogers likely heard the good news that Gage had sailed for England on October 11. While he did not have a close personal relationship with William Howe, a noted light infantry commander in his own right, Rogers had to have known that his prospects in the British Army had just significantly improved. Coincidentally or not, Rogers ended his conjugal visit after only a two-week stay and journeyed towards Boston which was surrounded by a cordon of Continental army fortifications.

Upon his arrival on the outskirts he notified George Washington, somewhat obsequiously and possibly duplicitously: “I do sincerely entreat your Excellency for a continuance of that permission for me to go unmolested where my private Business may call me as it will take some Months from this time to settle with all my Creditors—I have leave to retire on my Half-pay, & never expect to be call’d into the service again. I love North America, it is my native Country & that of my Family’s, and I intend to spend the Evening of my days in it.”[21]

Rogers did not know that Washington had already received a letter from Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, president of Dartmouth College, passing on rumors that Rogers had been sighted with the British forces in Canada as well as having “been in Indian habit through our encampments at St. Johns.”[22] The tabloids, once Rogers’ friend, also reported on his travels, going so far as to label him the commander-in-chief of the Indians.

Washington assigned Brig. Gen. John Sullivan, a New Hampshire lawyer who had yet to see combat, to interview Rogers before granting his continuance. Sullivan reported: “I am far from thinking that he has been in Canada but as he was once Governor of Michilimackinac it is possible he may have a Commission to Take that Command & Stir up the Indians against us & only waits for an opportunity to get there.”[23] In true lawyerly fashion, Sullivan suggested that Washington allow Rogers to travel on his existing pass, rather than grant him a new one, so that “Should he prove a Traitor Let the Blame Centre upon those who Enlarged him.”

Rogers continued on to New York to review again his land grants with Governor Tryon, but he also met with General Clinton, who was en route from Boston to South Carolina. Likely unbeknown to Rogers, a January 5 letter from Lord Germain to Howe had returned Rogers to good graces. In a memorandum, Clinton noted that he had probed Rogers about assuming a command, but Rogers demurred citing his promise to the Continental Congress.[24] Clinton’s account is somewhat suspect since it is unlikely that he saw Germain’s letter before he sailed from Boston.

Regardless of Rogers’ intentions, his wanderings clearly gave the appearance of espionage. With tensions running high, New York’s Committee of Safety banished him and other known Tories from the city over the course of the spring.

Rogers’ whereabouts are unknown until late June when he was arrested in New Jersey on General Washington’s orders. Washington was likely reeling from the discovery that week of the Hickey plot to assassinate him, fomented by Governor Tryon. It did not matter that Rogers was never incriminated in any way in this affair.

Washington interviewed Rogers personally, the only known meeting between the two tall warriors, both standing over six feet. Washington’s report to John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, highlighted his distaste for Rogers, bordering on personal jealousy, despite Rogers’professed desire to serve the Glorious Cause: “Upon information that Major Rogers was travelling thro’the Country under suspicious circumstances I thought it necessary to have him secured . . . the Major’s reputation, and his being an half pay Officer has increased my Jealousies about him . . . The Business which he informs Me he has with Congress is a secret Offer of his Service . . . I submit it to their Consideration, whether it would not be dangerous to accept.”[25]

While Washington was incarcerating Rogers, he was also corresponding with John Hancock to gain approval to employ Indians in the army.[26] Rogers might have assisted in this regard, yet Washington obviously had no interest in his help. Perhaps Washington felt his war council already had enough former British officers. Major Generals Charles Lee and Horatio Gates (who resigned their British commissions in 1772 and 1769, respectively), were already scheming against him.

Nevertheless, respectful of the travel pass granted by Congress, Washington allowed Rogers to go on to Philadelphia, albeit under guard. The city was agog with rumors of the Hickey plot, as Thomas Jefferson wrote to a friend: “the famous Major Rogers is in custody on violent suspicion of being concerned in the conspiracy.”[27] Fortunately for Rogers, Congress had much more important matters that month than an investigation of his activities, so his case was remanded to New Hampshire for adjudication.

Rogers had already been shipped across the continent to stand trial once in his life, he was not going to let it happen again. In an ironic twist, he escaped from Philadelphia while Congress finalized the Declaration of Independence. Eluding bounty hunters, he turned up on General Howe’s flagship off the coast of Staten Island ten days later.

With the King’s approval in hand, Howe commissioned Rogers to raise a regiment, the Queen’s American Rangers, which he did with gusto primarily in Long Island and Westchester. While his regiment once again bore the sobriquet Roger’s Rangers, little else resembled the famed unit of the French and Indian War. His recruits now were primarily “city” boys and farmers, many motivated by the opportunity to plunder their rebel neighbors, rather than hardened backwoodsmen defending their homes. Also, the terrain of battle had changed from impenetrable wilderness to coastal towns and plains, similar to the battlefields of Europe. Finally, the British army now had its own grenadiers and light infantry, drilled in ranger tactics right out of Rogers’ own handbook.

Although Rogers and his new unit met with skepticism, if not outright disdain, on their own side, they were monitored with more respect by their enemy. On August 30 William Duer, a prominent businessman and member of New York’s Committee of Safety, warned Washington: “one [William] Lounsbery in Westchester County who had headed a Body of about 14 Tories was kill’d by an Officer nam’d Flood, on his Refusal to Surrender himself Prisoner—That in his Pocket Book was found a Commission sign’d by Genl Howe to Major Rogers empowering him to raise a Battalion of Rangers.”[28]

Washington had much more to worry about than Rogers at the time. After saving his troops with a fortuitous naval evacuation from Brooklyn on August 30, he needed to regroup on Manhattan before the British launched another attack. He also faced the gut-curdling realization that the Continental Army could simply denigrate and disintegrate. On September 22, he wrote despairingly to Hancock: “Every Hour brings the most distressing Complaints of the Ravages of our own Troops who are become infinitely more formidable to the poor Farmers & Inhabitants than the common Enemy.”[29]

While Rogers and his Rangers were quite busy terrorizing rebel homes in September, Rogers also recorded his lone accomplishment of the Revolution, the capture of the Continental Army spy, Nathan Hale, on Long Island on the 21st, whom he transported to Manhattan. Hale was executed the next day at the artillery park near Howe’s country residence, the Beekman Mansion. His body hung for three days as a warning before being buried in an unmarked grave. Since Hale was likely sent out under direct orders from Washington, his apprehension might well have provided Rogers with a measure of revenge for his arrest earlier that summer.

Washington finally reacted to Duer’s warning on September 30 when he forwarded the news to Connecticut’s Governor Jonathan Trumbull: “Having received authentic advice . . . that the Enemy are recruiting a great number of men with much success . . . several have been detected of late who had enlisted to serve under their Banner and the particular command of Majr Rogers.”[30] Although Washington knew of Hale’s demise by then from a prisoner exchange conference conducted the day after his hanging, he might not have known Rogers’ role. Regardless, the commander-in-chief never formally recognized Hale’s sacrifice during or after the Revolution.

On October 4, Washington did petition Hancock, again invoking Rogers by name: “Nothing less in my opinion, than a suit of Cloaths annually given to each Non-commissioned Officer & Soldier, in addition to the pay and bounty, will avail, and I question whether that will do, as the Enemy . . . are giving Ten pounds bounty for Recruits; and have got a Battalion under Majr Rogers nearly compleated upon Long Island.”[31]

On October 12, a four thousand man British force marshaled by Howe himself sailed east from New York, final destination uncertain. As the British hopscotched along the Westchester coast, threatening Connecticut, Trumbull tracked Rogers: “a plan is forming by the Noted Majr Rogers a famous Partisan or Ranger in the last War now in the Service of Genl Howe on Long Island where he is Collecting a Battallion of Tories . . .who are perfectly acquainted with every inlet and avenue into the Towns of Greenwich, Stamford & Norwalk where are Considerable quantities of Continental Stores.”[32]

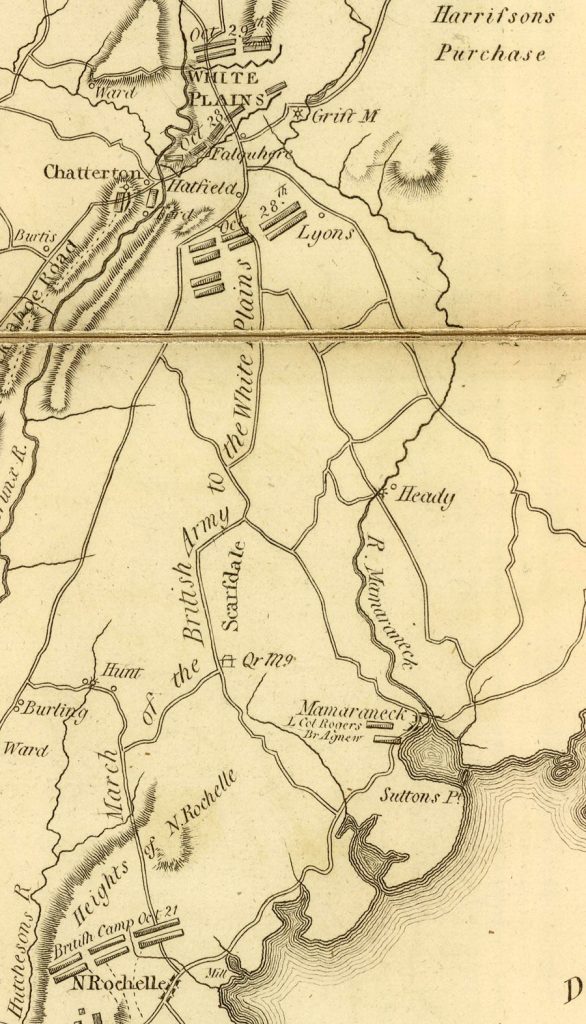

Rather than attack the supplies in Connecticut, Howe’s goal was to cut across Westchester from the Sound to the Hudson, trapping the Continental Army between British land and sea forces. When Howe finally marched inland on October 18, heading towards White Plains, he relied on the Queen’s American Rangers to secure the village of Mamaroneck and protect his eastern flank, a testament to his confidence in Rogers.[33]

In the same vein, the Americans realized that a defeat of Rogers would be both a tactical and publicity coup. As Washington marched north to counter Howe’s thrust, one of his most trusted generals, William Alexander, Lord Stirling (who had led the valiant but doomed charge against the Old Stone House in Brooklyn, been captured, and then exchanged) received intelligence on October 22, confirmed by the glow of campfires, pinpointing Rogers’position. He dispatched Col. John Haslet and 750 of his Delaware Blues, battle hardened in Brooklyn, to surprise the Rangers that night.

Local guides directed Haslet to approach the Rangers’encampment from the west, the direction of the main body of British troops, assuming correctly that sentries would be weakest here. Rogers headquartered in a school house in the village while his men, roughly 400 strong, bivouacked on nearby Heathcote Hill. Late that evening, the major, his battlefield senses as sharp as ever, repositioned a company of sixty men directly in Haslett’s path. The Continentals attacked, easily overrunning the newly established forward post, but the crack of muskets and shouts of melee awoke Rogers and his men. When Haslet pressed forward, falsely believing he had routed the enemy, his troops met with fierce resistance from the Rangers occupying the hillside. As Rogers personally rallied his men to withstand the rebel charge, Haslet withdrew, not only claiming victory but also the embarrassment of the vaunted Rogers.

On October 23 an unidentified officer wrote: “A party was detached against him [Rogers]; they killed many, took thirty-six prisoners, sixty-five muskets, and as many blankets, and completely routed the rest of the party. This blow will ruin the Major’s Rangers.”[34] A few days later, Haslet himself wrote of “Colonel Rogers’s, the late worthless Major. On the first fire, he skulked off in the dark.”[35] On a more realistic note, Lt. Col. Robert Hanson, Washington’s aide, reported to John Hancock: “by some accident or Another, the expedition did not succeed so well as could have been wished.”[36] On the British side, Howe explained to Lord Germain: “the carelessness of his sentries exposed him [Rogers] to a surprise from a large body of ye enemy by, w’h he lost a few men killed or taken; nevertheless by a spirited exertion he obliged them to retreat.”[37]

While Rogers did not play a notable role in the Battle of White Plains on October 28, the Rangers regrouped and continued to harass patriots, soldiers and civilians alike. Charles Lee delayed responding to Washington’s request in November to march to New Jersey in order to chase down a Rogers sighting in Westchester; after the Rangers “contracted themselves into a compact body very suddenly,” Lee chose to retreat rather than challenge the vaunted Rogers in combat.[38] In December, Westchester citizens petitioned the New York Provincial Congress for military assistance to defend their homes from both Rogers Rangers and Continental troops.

The Rangers were garrisoned at Fort Knyphausen in northern Manhattan in January 1777 when one of their captains, Daniel Strong, was captured while recruiting, and summarily executed. Rogers launched his last documented raid on January 13 against the home of Henry Williams in Bedford, absconding with a beaver hat, scarlet waistcoat, and sword among other items.[39]

By this time, Alexander Innis, newly appointed Inspector General of Provincial Forces, had claunched an investigation of the regiment. Innis, a Scotsman, began his American service in 1775 as secretary to the Royal Governor of South Carolina, Lord William Campbell, implying at least a middling level of education, breeding and wealth.[40] When explaining his review process in a letter to General Clinton three years later, Innis noted: “I found the Provincial Corps in very great confusion and disorder; Several persons to whom Warrants had been granted to raise Corps had greatly abused the confidence . . . Negroes, Mulattos, Indians, Sailors & Rebel Prisoners were enlisted, to the disgrace and ruin of the Provincial Service . . . their conduct in a thousand instances was so flagrant, that I could not hesitate to tell the General [Howe], that until a thorough reformation took place he could expect no service from that Battalion.”[41]

General Howe acted on Innis’s recommendations, replacing Rogers and twenty-two other officers by March, although Rogers continued to recruit through the spring. While the Rangers clearly were not gentlemen, they were likely no worse than many other troops on both sides of the conflict. Notably, Howe did not court martial any of the officers, instead retiring them with three months’ pay. There is no record that Rogers protested either Innis’s report or Howe’s action, perhaps a bargain he made with Howe in exchange for leniency towards his men.

Were Innis’s motives prejudiced against the “rabble” of the Rangers or purely for the good of the Army? Col. Rudolph Ritzema, who deserted from patriot forces in November 1776 after a falling out with General Stirling and served the British Army through 1778, described Innis as “a man, whose haughty and supercilious conduct has estranged more minds from His Majesty and the British Govt. than perhaps all the other blunders in the conduct of the American war put together.”[42] Nevertheless, Innis continued to serve with distinction. After completing his stint as a staff officer, he returned to the front lines, leading troops into battle at Musgrove’s Mill in South Carolina in 1780 where he was wounded and subsequently dropped from view.

In April, George Washington again voiced his personal concern, noting, “Rogers is an active instrument in the Enemy’s hands, and his conduct has a peculiar claim to our notice . . . If it is possible, I wish to have him apprehended and secured.”[43] He need not have worried.

Rogers headed steadily downhill after his dismissal by Howe. Now an “old man” of forty-five, weakened by years of captivity and alcohol, he tried one more time to raise a company of Rangers, but ended up once again in jail. His wife divorced him in 1778, while his older brother sadly apologized in 1780; “the conduct of my brother of late almost un-mans me . . . I am sorry his good talents should so unguarded fall a prey to intemperance.”[44]

Rogers ultimately returned to England with the evacuating British troops in 1783 and died destitute in London in 1795. Perhaps his greatest “crime” was his rise from low birth to great fame. Robert Rogers was always a backwoodsman, never an aristocrat, plantation squire, lawyer, bookseller, or prosperous merchant as were the other leading military figures of his times. On the other hand, Rogers’ legacy of ranger tactics, wilderness exploration, and continental expansion has endured. “Rangers lead the way” remains the motto of the US Army Ranger Corps to this day.

[1]John F. Ross, War On The Run (Bantam Books, New York, 2009) (imputed page#)121/(Kindle location)1994; Boston GazetteFebruary 14, 1757, 2.

[2]Ross 284/4678; Boston Weekly Newsletter, February 7,1760; 1.

[3]Ross 323/5310; New Hampshire Gazette, February 27, 1761.

[4]Stephen Brumwell, White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery and Vengeance in Colonial America (De Capo Press. Cambridge, MA, 2004).

[6]Robert Rogers, A Concise Account of North America (original edition London 1765; Heritage Books, Westminster, MD 2007), VI.

[7]mynorth.com/2010/05/before-lewis-clark-carver-tute-set-out-to-find-the-northwest-passage/.

[8]David A. Armour, Treason? At Michilimackinac: The Proceedings of a General Court Martial held at Montreal in October 1768 for the Trial of Major Robert Rogers (Mackinac Island State Park Commission 1967), 9.

[9]Ross, War On The Run, 423/6956.

[10]John R. Alden, General Gage in America (Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, Louisiana; 1948),26.

[11]Ron Chernow, Washington: A Life (Penguin Books, New York 2010), 59;

George Washington to Robert Dinwiddie July 18,1755, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-01-02-0168.

[12]Thomas Gage to Washington, November 23,1755, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-02-02-0183.

[13]Boston Gazette, March 1, 1756.

[14]Alden, General Gage in America, 30.

[15]Washington to William Crawford September 25, 1773,founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-09-02-0255.

[16]Washington to Bryan Fairfax July 20,1774, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/02-10-02-0081.

[17]John R. Cuneo, “The Early Days of the Queen’s Rangers August 1776-February 1777,” Military Affairs, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Summer, 1958), 65-74; Memorandum of King George, April 1, 1775, Sir John Fortescue, ed., The Correspondence of King George the Third. Vol. III, July 1773-December 1777 (London, 1928), 195-196.

[18]George Athan Billias, George Washington’s Opponents (New York: William Morrow, 1969), 26.

[19]www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/battles-of-lexington-and-concord.

[20]John Adams Diary, September 21, 1775, Massachusetts Historical Society, www.masshist.org/digitaladams/archive/doc?id=D24&hi=1&query=Rogers&tag=text&archive=diary&rec=1&start=0&numRecs=7.

[21]Robert Rogers to Washington, December14, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0505.

[22]Eleazar Wheelock to Washington, December 2, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0429.

[23]John Sullivan to Washington, December 17, 1775, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0522.

[24]Cuneo, “The Early Days of the Queen’s Rangers,” 66.

[25]Washington to John Hancock, June 27, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0079.

[26]Washington to Hancock, June 8, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-04-02-0367; Hancock to Washington June 18,1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-05-02-0018.

[27]Thomas Jefferson to William Fleming, July 1, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-01-02-0175.

[28]William Duer to Washington, August 30, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0137.

[29]Washington to Hancock, September 22, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0287.

[30]Washington to Jonathan Trumbull, September 30, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0340.

[31]Washington to Hancock, October 4, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0358-0001.

[32]Trumbull to Washington, October 13,1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-06-02-0422.

[33]Cuneo, “The Early Days of the Queen’s Rangers,” 70.

[34]Peter Force, ed., American Archives, Fifth Series. Vol. II (Washington, DC: Peter Force, 1851), 669.

[36]Robert Hanson Harrison to Hancock, October 25, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0021.

[37]Cuneo, “The Early Days of the Queen’s Rangers,” 71.

[38]Charles Lee to Washington, November 30, 1776, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-07-02-0169.

[39]Cuneo, “The Early Days of the Queen’s Rangers,” 73.

[40]www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/alexander-innes.

[42]E. Alfred Jones, “A Letter Regarding the Queen’s Rangers,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 30, no. 4 (1922), 368–76.

[43]Washington to Trumbull April 12, 1777, founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-09-02-0137.

5 Comments

Scott

I read your article with great interest. My first history book was Rogers’ Rangers and the F&I War and ever since that time I have looked for any information on Rogers. Always wonder why his “best” friend John Stark never stepped up to give a good word on Rogers. Overall your article is well written, clear, well supported and very informative.

Mr. Smith:

Thanks for your excellent overview of Roger’s Revolutionary War exploits. Your readers may also be interested in the definitive all-inclusive biography of Robert Roger’s by renowned military artist/historian Gary S. Zaboly, A True Ranger (Garden City Park, NY: Royal Blockhouse, LLC, 2004) and, for Roger’s earlier career (in addition to the sources you cited-Armour, Brumwell), the definitive published version of Roger’s own journals by Roger’s Rangers author/historian Timothy J. Todish, The Annotated and Illustrated Journals of Major Robert Rogers; Illustrated by Gary S. Zaboly (Fleischmanns, NY: Purple Mountain Press, 2002).

Apologies for the typos! Should be Rogers and Rogers’.

For some reason, I was thinking Rodgers and Hammerstein….

“While he did not have a close personal relationship with William Howe, a noted light infantry commander in his own right” he did have a close relationship with his brother Brig. Gen. George Howe.

George Howe who became Gen. Ambercombie’s second in command was really dedicated to instilling the tactics of American Ranger units of Robert Rogers, John Stark and Israel Putnam as the best way to prosecute the war in America. He sent Rogers on scouting missions and accompanied him on one on the French at Ft. Carillion (Ticonderoga). Sadly on July 6, 1758, while on another mission with Putnam’s Connecticut troops – George Howe was killed.

It is felt by a few historians that William Howe supported the ‘disgraced” half-pay Robert Rogers because of his ties to his brother George.