On April 24, General Gage sent his account of the confrontations at Lexington and Concord aboard the 200-ton, cargo-ladened Sukey to Lord Barrington, the Secretary of War and to the Earl of Dartmouth, the Secretary of State for the Colonies.[1] His letter to Lord Barrington, written on the 22nd, began with an understated opening sentence: ‘”I have now nothing to trouble your Lordship with, but of an affair that happened here on the 19th instant.” Something must have quickly changed his perception of the confrontations because the next day he sent a dispatch to Admiral Graves asking that

“Captn [John] Bishop to examine every letter on board her those directed for Docr [Benjamin] Franklin, [Arthur] Lee, [William Bollan] Borland &c to be sent to Boston; any other Suspicious letters to be put under Cover to the Secretary of State, and given to Lieut [Joseph] Nun, Capn Bishop telling his Lordship, that he was directed in this Critical Juncture, to send him the Inclosed for his perusal, as they might contain some Intelligence of the Rebels here –“[2]

Determined to get the colony’s version of the confrontations to England first, on April 22 the Second Provincial Congress of Massachusetts appointed a committee of nine to take depositions, “from which a full account of the Transactions of the Troops under General Gage, in their route to and from Concord, etc … on Wednesday last, may be collected.”[3] The committee interviewed 97 people in three days and secured signed, sworn statements from all of them. Each person deposed was administered an oath by a justice of the peace whose “good faith” was certified by a notary public. The main point of all the depositions was that no provincial at either Lexington or Concord fired until the British had fired first. On April 25, the Provincial Congress rushed to have the depositions included in “A Narrative, of the Excursions and Ravages of the King’s Troops Under the Command of General Gage, on the nineteenth of April, 1777: Together with the Depositions taken by order of Congress.” The account was written by Benjamin Church, Elbridge Gerry and Thomas Cushing;[4] it was printed by Isaiah Thomas of Worcester.[5]

Needing the fastest vessel they could find, Richard Derby, Jr., a member of the Congress, agreed to outfit one of his vessels, the Quero, and his younger brother, John Derby, Esq., would command her. On April 27, General (Dr.) Joseph Warren gave him his orders:

“Resolved, That Capt. Derby be directed and he hereby is directed to make for Dublin or any other good port in Ireland, and from thence to cross to Scotland or England and hasten to London. This direction is given that so he may escape all enemies that may be in the chops of the channel, to stop the communication of the Provincial intelligence to the agent. He will forthwith deliver his papers to the agent on reaching London.”[6]

The papers were a “letter of instruction” for Benjamin Franklin,[7] a copy of the depositions, a letter from Dr. Joseph Warren titled “To the Inhabitants of Great Britain”[8] and copies of Essex Gazette that contained the colonists’ account of the confrontations.[9]

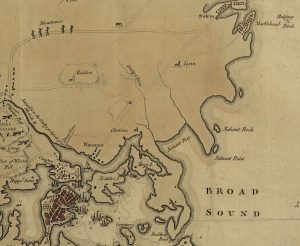

On the night of April 28, Capt. John Derby and the Quero set sail from Salem. The Quero was a fast, 62-ton schooner. On this trip it would carry no cargo, only ballast. In the postscript to his instructions from Dr. Warren, Capt. Derby was told “You are to keep this order a profound secret from every person on earth.” In fact, “the crew [did not] know their destination ‘till they were on the banks of Newfoundland.”[10]

Disregarding Warren’s instructions, Derby sailed directly to the Isle of Wight in the English Channel, secured transportation to Southampton and then made his way to London where he arrived on May 29. His entire trip took four weeks.

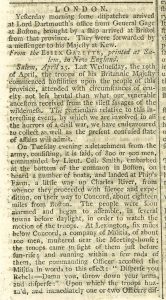

He delivered the papers to Arthur Lee, Franklin’s successor, because Franklin had recently sailed for Philadelphia. Copies of the depositions were made and the originals were placed in the custody of John Wilkes, a radical who espoused the American cause, who also happened to be the Lord Mayor of London.[11] The next day the depositions and the Essex Gazette account appeared in the London Evening Post. Other newspapers picked up the story and within a few days the entire country knew of the confrontations. It caused a sensation among those sympathetic to the colonies, but caught the ministry by surprise.

The former governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, who was now serving as an “advisor” to the Secretary of State for the American Colonies, “carried the news to Lord Dartmouth, who was much struck [by] it. The first accounts were very unfavorable, it not being known that they all came from one side. The alarm abated before night, and we wait with a greater degree of calmness for the accounts from the other side.”[12] The next day, May 30, Dartmouth published the following bulletin in a government gazette:

“A report having been spread, and an account having been printed and published, of a skirmish between some of the people in the Province of Massachusetts Bay and a detachment of His Majesty’s troops, it is proper to inform the publick that no advices have as yet been received in the American Department of any such event. There is reason to believe that there are dispatches from General Gage on board the Sukey, Captain Brown, which, though she sailed four days before the vessel that brought the printed accounts, is not arrived.”[13]

Arthur Lee responded by publishing the following notice: “All those who wish to see the original affidavits which affirm the account are deposited in the Mansion House with the Right Lord Honorable Mayor for their inspection.”[14]

On May 31, Hutchinson wrote to Gen. Gage,

“The arrival of Captain Darby from Salem on the 28th with dispatches from the Congress at Watertown, immediately published in the papers, caused a general anxiety in the minds of all who wish the happiness of Britain and her Colonies. I have known the former interesting events have been partially represented: I therefore believe with discretion the representation now received. It is unfortunate to have the first impression made from that quarter … It is said your dispatches are on board Cap. Brown, who sailed some days before Derby. I hope they are at hand and will afford us some relief.”[15]

While the ministry was waiting for the arrival of the Sukey, every effort was made to locate Derby and his ship. The harbor and nearby waterways of Southampton were searched but with no success.

Dartmouth was frustrated. Three times he had summoned John Derby to appear before him and three times he failed to show up.[16] Little did he know that on June 1, Capt. Derby had left London. The Quero was no longer in an inlet on the Isle of Wight but rather in the harbor at Falmouth. When he arrived he paid the custom inspection and clearance fees and prepared his ship for departure.

On June 3, Hutchinson recorded the following in his diary:

“Went to Lane and Fraser’s … the London correspondents of the Derby family. Found that Captain Darby had not been seen since the first instant; that he had a letter of credit from Lane on some house in Spain. Afterwards I saw Mr. Pownall [assistant Secretary of State under Lord Dartmouth] at Lord Dartmouth’s office, where I . . . and Pownall was of opinion Darby was gone to Spain to purchase ammunition, arms, &c. We are still in a state of uncertainty concerning the action in Massachusetts. Vessels are arrived at Bristol, which met with other vessels on their passage, and received as news that there had been a battle, but could tell no particulars.”[17]

On June 9, the Sukey arrived in Southampton; unaware of the urgency that awaited his arrival, Captain Brown did not deliver the dispatches to Lord Dartmouth until the next day. Hutchinson’s diary contains this entry for June 10:

“A lieutenant in the navy [Joseph Nunn] arrived about noon at Lord Dartmouth’s office. Mr. Pownall gave me notice, knowing my anxiety; but though relieved from suspense, yet received but little comfort, from the accounts themselves being much the same with what Darby brought. The material difference is the declaration by Smith, who was the commander of the first party though not present at the first action, that the inhabitants fired first, and returns show only 63 were killed outright, yet 157 were wounded, and 24 missing; which upon the whole is a greater number than Darby reported…”[18]

The dispatches confirmed what the newspapers had been saying, with the exception of Gen. Gage’s claim that the colonists had fired first. Dr. Warren had hoped that the account of the confrontations, the depositions and his letter would lead to an end to any further bloodshed. He wrote, “Lord Chatham and our friends must make up the breach immediately or never. The next news from England must be conciliatory, or the connection between us ends, however fatal the consequences may be.” When Dartmouth presented the dispatches to the King, he reacted angrily. He had no intention of entering into talks with his subjects who were now engaged in a rebellion.

Three weeks later, Lord Dartmouth sent the following dispatch to General

Gage:

“Sir: On the 10th of last month in the morning, Lieutenant Nunn arrived at my office with your despatch containing an account of the transaction on the 19th of April of which the public had before received intelligence by a schooner, to all appearances sent by the enemies of government, on purpose to make an impression here by representing the affair between the King’s troops and the rebel Provincials in a light the most favorable to their own view. Their industry on this occasion had its effect, in leaving for some days a false impression upon people’s minds, and I mention it to you with a hope that, in any future event of importance, it will be thought proper … to send your dispatches by one of the light vessels of the fleet.”[19]

On July 19, the Quero arrived in Salem, however Derby was not on board. He had gone ashore earlier and left William Carlton, his sailing master, in command. He was already making his report to General Washington and the provincial Congress.[20]

On August 1, the Provincial Congress of Massachusetts approved Capt. Derby’s personal expense report. He submitted charges totaling 57 pounds, 8 pence; he did not submit an expense for his services.[21]

[1] Edwin Carter, ed., “Gage to Barrington, April 22, 1775,” The Correspondence of General Thomas Gage with the Secretaries of State, and with the War Office and the Treasury, 1763-1775 (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1969), 2:673-4; “Gage to Dartmouth,” Ibid., 1:396.

[2] “Gage to Admiral Graves, 23 April 1775,” Naval Documents of The American Revolution (Washington DC: G.P.O., 1964), 1:211.

[3] Peter Force, ed., American Archives, 4th Series, 2:765.

[4] Naval Documents, 1:212.

[5] http://www.masshist.org/revolution/docviewer.php?old=1&mode=nav&item_id=667

[6] “Committee of Safety Resolution, 27 April 1775,” Journals of each Provincial Congress of Massachusetts in 1774 and 1775, and of the Committee of Safety (Boston: Dutton and Wentworth, 1838), 159.

[7] William B. Willcox, ed., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982), 22:29–30.

[8] “Provincial Congress to the Inhabitants of Great Britain.” April 26, 1775, Force, American Archives, Series 4, 2:487-88.

[9] Ralph D. Paine, The Ships and Sailors of Old Salem (New York: The Outing Publications Co., 1909), 191.

[10] Robert S. Rantoul, “The Cruise of the ‘Quero’: How We Carried the News To the King,” The Essex Institute Historical Collections, 36#1 (1900), 8.

[12] Fred J. Hinkhouse, The Preliminaries of the American Revolution as Seen in the English Press, 1763-1775 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1926), 183-97.

[12] Thomas Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters of His Excellency Thomas Hutchinson, Peter Orlando Hutchinson, ed. (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1883), 1:455.

[13] Rantoul, “The Cruise of the ‘Quero’,” 6.

[14] Ibid., 6-7.

[15] Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters, 456-7.

[16] Benjamin Franklin Stevens, “John Pownall to Lord Dartmouth, dated 29 May 1775,” British Accounts of the American Revolution, Vol. VII, American Revolutionary War Series (Great Britain: Historical Manuscripts Commission, 1887), 304.

[17] Hutchinson, The Diary and Letters, 463-4.

[18] Ibid., 466.

[19] Robert S. Rantoul. A Collection of Historical and Biographical Pamphlets (Salem, 1881), 240.

[20] “George Washington to John Hancock, 21 July 1775,” The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, Vol. 1, Philander D. Chase, ed., (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1985), 143-44; “James Warren to John Adams, 20 July 1775,” The Adams Papers, Robert J. Taylor, ed., (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1979), 3:82-85.

[21] Peter Force, American Archives, Series 4, Vol. 3, 298.

Recent Articles

That Audacious Paper: Jonathan Lind and Thomas Hutchinson Answer the Declaration of Independence

Supplying the Means: The Role of Robert Morris in the Yorktown Campaign

Revolution Road! JAR and Trucking Radio Legend Dave Nemo

Recent Comments

"Eleven Patriot Company Commanders..."

Was William Harris of Culpeper in the Battle of Great Bridge?

"The House at Penny..."

This is very interesting, Katie. I wasn't aware of any skirmishes in...

"Texas and the American..."

Mr. Villarreal I would like to talk to you about Tejanos who...